You hoist one of Colorado’s fine craft beers at the long, dark bar of the Silver Dollar Saloon in Leadville, and consider this possibility: had history played out a little differently, Oscar Wilde and Doc Holliday might have exchanged bon mots right at this spot.

Both caroused here, Wilde in 1882, Holliday a year later. They both provided memorable episodes in a wild mining town with a thick Irish vein running through its history.

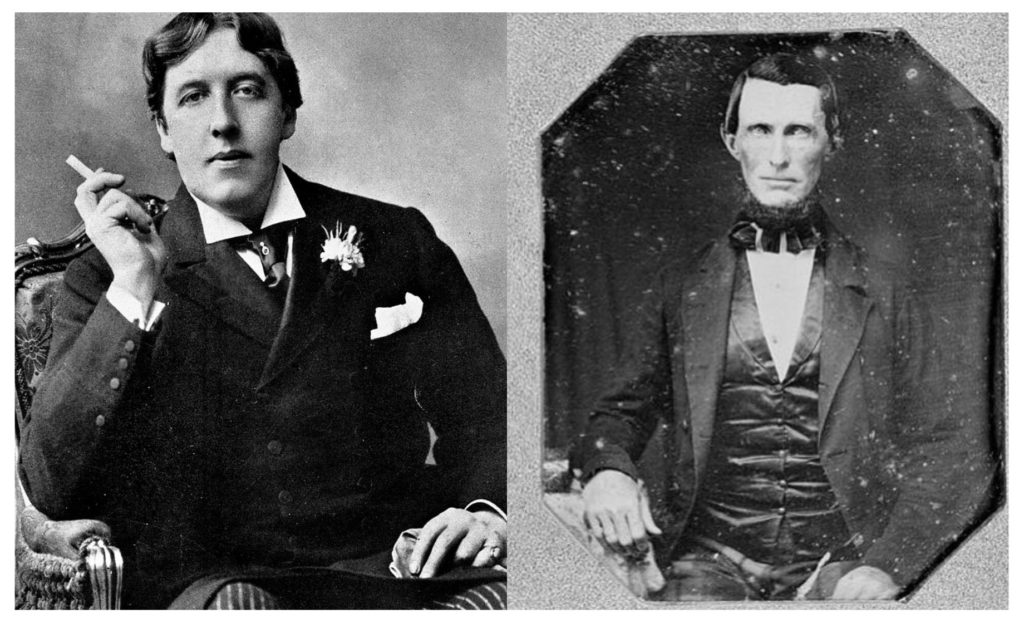

Wilde, the Dublin wit and writer, likely would have been fascinated with the storied gunslinger, gambler and dentist Holliday, grandson of a Belfast couple who immigrated to Georgia. One spat words, the other bullets.

During a western trip in which he embraced the region’s rugged individualism while lecturing on Florentine culture and interior design, among other things, Wilde charmed silver miners in an appearance at the Tabor Opera House.

But it was his post-lecture appearance at the Silver Dollar and his willingness to descend a shaft at the Matchless Mine which really won over his audience.

Wilde’s prodigious capacity for drink impressed folks who made an art of imbibing and over the years melded into myth as his visit to the mine was embellished.

The story grew into a tale of how miners took Wilde down the mine shaft with an eye to getting him drunk, then leaving him there for a scare.

But in a twist, it was the miners who were bested in the drinking department, as the yarn goes, and Wilde had to operate the lift to get everyone out.

Leadville historian Roger Pretti takes the legs out from under that story by pointing out that the apparatus transporting miners up and down at the time was crude.

“They were basically barrels sawed in half and could take one or two men at a time.”

The more accurate story is that Wilde was invited the next day to open a new lode of silver in the mine, an honor bestowed on famous visitors. The lode was named “The Oscar.”

Wilde later recounted that his visit to the Silver Dollar uncovered “the only rational method of art criticism I have come across. Over the piano was a printed notice — ‘Please do not shoot the pianist, he is doing his best.’”

And of his visit to Leadville in his “Impressions of America” he later wrote, “I was told that if I went there they would be sure to shoot me or my travelling manager. I wrote and told them that nothing that they could do to my travelling manager would intimidate me.”

Speaking of shooting, Holliday’s time in Leadville followed the infamous 1881 Gunfight at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona Territory.

Courts cleared Holliday, Wyatt Earp and two Earp brothers of murdering three in the 30-second, 30-bullet shootout.

But Holliday was back in trouble in Leadville when he shot vowed enemy Billy Allen after Allen showed up in town, according to the Leadville historical society webpage. Holliday waited at the end of a bar in Hyman’s Saloon and shot Allen in the arm, then missed a head shot before being disarmed.

A local court found Holliday not guilty of attempted murder.

Leadville is a lot more civil place now, a destination 100 miles from Denver and at 10,052 feet elevation, the highest incorporated town in North America.

Both men were attracted to the town of 18,000, then second largest in the state, by the riches derived from first gold, then silver and lead. Wilde was paid handsomely to bring culture. Holliday sought out wealthy but poor card players.

To get Leadville’s measure, and a measure of history, the Delaware Hotel is a good place to start. It’s a living museum, built in 1888, that has preserved in a rich decor and exhibits of finery of the day.

That’s where we met Pretti, a former newspaper man who runs history tours and dresses like a man of the time of Wilde and Holliday.

We asked for a driving tour with an Irish flavor. And there was plenty outside of those famous folks. The tour took us up to about 12,000 feet, more than two miles above sea level, for stories of the mines and the heady times of fortunes made and lost.

Perhaps the most famous of those mining windfalls belonged to the “Unsinkable” Molly Brown, born Margaret Tobin to Irish immigrants.

She settled in Leadville in 1886 as a single woman but soon married mine engineer J.J. Brown, according to archives of the Molly Brown House Museum in Denver. His discovery of gold in the Little Johnny Mine made the couple millionaires.

They moved to Denver and Molly began her world travels, climaxed by passage on the Titanic in 1912. She famously helped comfort distressed passengers and raised $10,000 from rich friends to help folks on the ship who lost everything in the sinking.

Asked about her survival in the disaster, she replied, “Typical Brown luck. We’re unsinkable.”

But many who answered the lure of gold and silver were down on their luck, and the mix of poor immigrants made for tense times.

As Pretti explains, the town was divided into two camps by Main Street. The Irish occupied the upper slope and a community of Eastern European settlers in the lower slope.

“If you strayed into the other’s community it could get ugly,” he noted.

Irish activity centered on the saloons and the Church of the Annunciation, built in 1879 and the site of Molly Brown’s wedding.

Irish immigrants poured into the boomtown through Mosquito Pass, a treacherous portal at more than 13,000 feet elevation.

Driven by poverty, many stayed impoverished. Others, like the Gallagher brothers, struck it rich and left for parts unknown.

Identified in the Leadville/Lake County Heritage Guide as John, Charles and Patrick, “they were an example of people who went from poverty to extreme riches,” offers Pretti.

One account says the brothers were simply acting on good advice when they made their discovery. But a version that has persisted, Pretti says, is a classic “luck-of-the-Irish” yarn.

Their pot of gold came when one brother literally tripped over the site of an extensive silver lode. That and superstition made them very rich men.

Pretti explains he was stumbling home from a night at the saloon when he tripped on a tree root. In a comical sequence, “his boot unearthed a rock which shot up and hit him in the head.”

As he explained his pratfall to his siblings the next morning, one took it as a sure sign there was a fortune at the location, claiming it was the work of “mountain fairies.”

The brothers visited the site, dug down 15 feet and found a rich vein of silver.

“The Gallaghers made a lot of money out of the mine, which was called Camp Bird, then sold it for $250,000 and headed out into the world, lost to history.”

True or not, it’s part of the rich Irish thread woven into the fabric of one of America’s classic boomtowns.

John Kernaghan is based in Oakville, Ontario.

This is a great story, but I have one correction: Leadville’s altitude is 10,152, not 10,052. Another great Leadville story is that of Jesse F. McDonald who also came to Leadville in search of riches, found his fortune and became governor in 1905 after the state’s most corrupt election. You can read more about him on my website. It is an honor to live in the grand house he built here in Leadville!

Thanks, I enjoyed this. You know Yeats said the Irish had produced the two most identifiable great writers in his time – immediately identifiable from their style – Wilde and Shaw.

What an amazing people the Irish – a gold and silver mine themselves – that they continue to produce riches after so many centuries of murder and abuse. Phenomenal. Let’s comprehend them!

Best wishes!

Peadar Garland

Lovely story but a little correction to the bit at the end about the Camp Bird Mine. It’s not in Leadville, but Ouray, about 38 miles north of Durango. I have 3 pieces of ore from the mine that came from my grandfather, born in Durango in 1895 to Irish immigrants, who arrived there in 1881. The mine was discovered by Thomas Walsh, whose daughter later owned the Hope Diamond and the Washington Post.