Pat Fenton remembers his old pal

As sure as Brendan Behan had his Dublin, Ireland, Seamus Heaney had his Northern Ireland, and Dylan Thomas had his Swansea, Wales, Pete Hamill had his Brooklyn. And like them, he wrote about it his whole life. And like them, he was always pulled back home again. And he did it with this literary skill that only comes along every so often. Sadly he’s gone from us now, but like these other great writers his words will stay with us forever.

Listen to him describe a rainy night in 1970 where he’s sitting at a table with Frank Sinatra in P.J. Clark’s saloon in New York: “On this night in the rain-drowned city, we were safe and dry at an oak table in the back room of the saloon. Clarke’s was , and remains, a place out of another time, all burnished wood, and chased mirrors, Irish flags and browning photographs of prizefighters.

Terry Golway remembers the mentor who became a friend

Here’s the thing about Pete Hamill – he was one of the nicest people I’ve ever met. And there are countless journalists now of a certain age who will tell you the same thing – they worshipped the guy, maybe got into the business because of his columns in the Daily News, and when they met him for the first time, he greeted you like an old friend.

Here’s the thing about Pete Hamill – he was one of the nicest people I’ve ever met. And there are countless journalists now of a certain age who will tell you the same thing – they worshipped the guy, maybe got into the business because of his columns in the Daily News, and when they met him for the first time, he greeted you like an old friend.

Extraordinary, really.

I don’t remember when I met him – it must have been in the late 1980s, when I was in my early 30s and trying to figure out how to cross the longest five miles in the world – the distance between Staten Island and Manhattan. The circumstances are as vague as the time line, but I do remember vividly that great baritone as he insisted that I call him “Pete” and not, as I had, “Mr. Hamill.”

Ted Smyth pays tribute to a generous friend of Glucksman Ireland House

Three years ago, I read Pete Hamill’s essay, “Notes for the New Irish: A Guide for the Goyim,” in New York magazine’s special Irish Edition in March 1972. What a revelation that turned out to be. Lurking behind the cover of a vivid, burning green Irish harp, between ads for Benson and Hedges and Sony stereos, Pete wrote one of the best descriptions ever of the changing nature of Irish identity in America. Jack Deacy, then a 27-year-old hell-raiser fresh back from Belfast, had successfully convinced editor Clay Felker that if the Chinese could have a special edition, so could the Irish. Gail Sheehy wrote a vivid account of the “Fighting Women of Ireland” from Belfast, Dennis Duggan profiled Judge Comerford, and Joe Flaherty rightly observed that ‘The Irish mess’ is not due to some genetic defect in the Irish character. It is, to be accurate, a British mess.” (My thanks to Professor Marion Casey at Glucksman Ireland House NYU for suggesting I read the special edition.) Read more.

Three years ago, I read Pete Hamill’s essay, “Notes for the New Irish: A Guide for the Goyim,” in New York magazine’s special Irish Edition in March 1972. What a revelation that turned out to be. Lurking behind the cover of a vivid, burning green Irish harp, between ads for Benson and Hedges and Sony stereos, Pete wrote one of the best descriptions ever of the changing nature of Irish identity in America. Jack Deacy, then a 27-year-old hell-raiser fresh back from Belfast, had successfully convinced editor Clay Felker that if the Chinese could have a special edition, so could the Irish. Gail Sheehy wrote a vivid account of the “Fighting Women of Ireland” from Belfast, Dennis Duggan profiled Judge Comerford, and Joe Flaherty rightly observed that ‘The Irish mess’ is not due to some genetic defect in the Irish character. It is, to be accurate, a British mess.” (My thanks to Professor Marion Casey at Glucksman Ireland House NYU for suggesting I read the special edition.) Read more.

Terry George canonizes his dear friend

I’ve met a few true geniuses in my life: the actor Daniel Day Lewis, the orator Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, the musician Van Morrison. I’ve been lucky to meet a few living saints; Bishop Desmond Tutu, the priest Desie Wilson, but I’ve met only one genius/saint; a person who combined almost unquantifiable talent in a particular field combined with a level of decency, humanism and brotherly love that seemed otherworldly. That person was Pete Hamill, who died this week.

Pete would hate this description. His spoke of himself only as “a writer,” who liked almost everyone. Ask him how he became famous and he’d shrug it off. “Whatever success you have,” he once said, “You rode in on the shoulders of giants.” The giants he referred to were not only the great old newspapermen he worked with, but the classical writers he studied and loved; Voltaire, Dickens, Joyce, Heaney.

Pete Hamill read ravenously. He consumed knowledge like most people consume food. I know this because I worked as his researcher back in the heady days of the 80s. I presented him with volumes on everything from the building of the Brooklyn Bridge, to the San Patricios Brigade, to development of the MS-Dos computer language. He took that information, consumed it and then produced prose that read like poetry in its most efficient and lyrical form. He did this with a joy in his work process that was frankly scary. And then he’d sit and explain the process to me in the most generous way. Read more.

Tom Deignan on his favorite Hamill piece

The year was 1997 and I was fresh out of college, with a head full of words and dreams, an ambition to tell stories that were not being told, and to dive into the hurly-burly of big ideas about America and the world.

The year was 1997 and I was fresh out of college, with a head full of words and dreams, an ambition to tell stories that were not being told, and to dive into the hurly-burly of big ideas about America and the world.

In other words, I really needed a job.

By then I had already been corresponding (which is to say, pestering) great wordsmiths and storytellers like Peter Quinn and Terry Golway, who made the mistake of tolerating, even encouraging, me.

Pete Hamill made the same mistake. It led to what I consider the greatest piece of writing Hamill ever did.

I can’t pretend to have known Hamill in any kind of personal way. Our paths crossed plenty of times, and several times when he put a new book out I had the honor of sitting across from him and listening. The Lion’s Head. Thomas Nast. Walter O’Malley. Mychal Judge. My own private Ken Burns documentary.

The thing that struck me this week, reading the remembrances following Hamill’s death at the age of 85, was not just the impressive range of his work, but how generous he was with aspiring writers. Read more.

Pete Hamill EXTRA

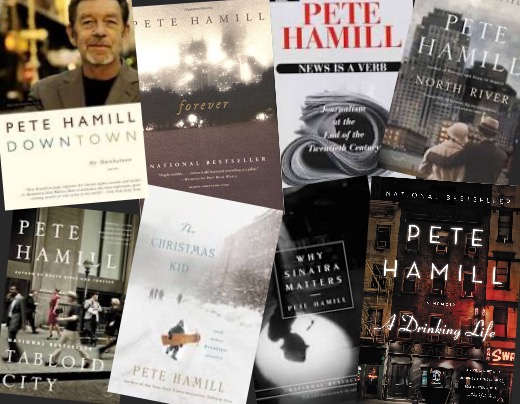

Irish America Editor-in-Chief Patricia Harty interviewed Pete Hamill in 2003 following the release of his novel, Forever. Forever Hamill.

New York Times reporter and columnist Dan Barry recalls spending a day with Pete Hamill in Scones for Pete Hamill.

Adam Farley profiled Pete Hamill for his induction into the Hall of Fame in 2016.

Listen to Pete’s Hall of Fame speech from March 2016.

Pete Hamill wrote about JFK for our Irish American of the century in 1999.