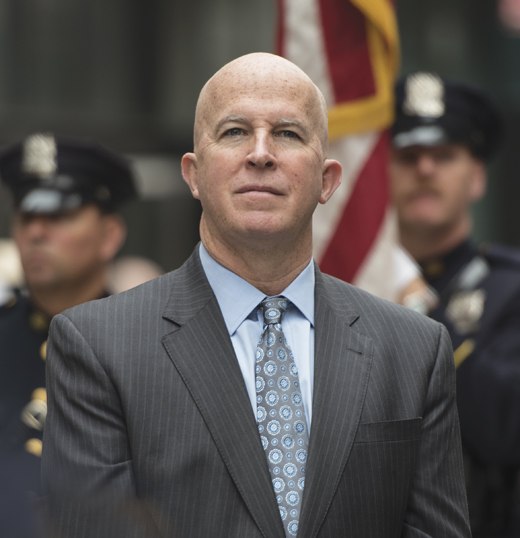

“Jimmy’s not just a cop’s cop. He’s a New Yorker’s New Yorker.” When it comes to James O’Neill, New York City’s 43rd and current police commissioner, those words by Chirlane McCray, the wife of N.Y.C. Mayor Bill de Blasio, could not be more spot-on.

A more fitting NYPD commissioner couldn’t be found in Central Casting. He is a steadfast New Yorker who started his career guarding the treacherous 1980s subways and has since held almost every rank in the department. His first day as commissioner saw a bomb exploding in Manhattan. He likes hockey, motorcycles, and war biographies. He loves his mom, his sons, and Irish soda bread.

“I’m proud of my Irish heritage,” he says when he meets with the Irish America team at his office in One Police Plaza, “and I’m proud of being American, also. It’s all helped me be who I am.” He jokes that his sons, who are only half Irish, completely identify as being 100 percent.

His sons, now grown, are Danny and Christopher. Danny is 29, works for an insurance company, and is engaged to be married. Christopher is 25 and works at the NYPD doing video production in the office of the Deputy Commissioner of Public Information.

O’Neill grew up in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, on a block with about 50 kids on it, and he knew them all. “I didn’t know the people around the corner on 31st Street,” he said. “That was a different world. But I knew everybody on 32nd.”

Seven of those 50 kids were O’Neills. “Every summer day,” he said, “my mom would throw us out at eight o’clock in the morning, feed us at lunchtime, throw us back out, and we’d come back in for dinner.”

Their father, Joseph O’Neill, would work around the house on the weekends listening to the Clancy Brothers and other Irish music on Fordham radio station’s popular Irish program, Ceol na nGael.

His dad used to say their ancestors were “The Royal O’Neills,” while his mom would give him a jab in the ribs, teasing, “Oh, yeah. Sure we were – the kings and queens!”

O’Neill’s maternal grandparents, Joe and Mary Kelly, came to the United States from County Longford. He spent a lot of time with his grandmother. Every Friday night, Helen O’Neill would put James and his brother on the bus at Beverly and Nostrand Avenue, and their grandmother would pick them up in her neighborhood, about 30 minutes away.

His grandfather Joe was a hardworking, funny man who worked numerous jobs, including as a taxi driver and in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He passed away when O’Neill was seven years old, but not before leaving a memorable impression. As O’Neill put it, “He did this, did that, probably drank too much, had a little too much fun – but he treated us like gold.”

His paternal grandparents came from County Monaghan. They lived on the same block as the O’Neills in Brooklyn. “My dad’s father didn’t show it quite as much,” O’Neill said, “but he was always looking after us.” He was a tall, stern man who worked for the telephone company. He came over to the United States after living up against the border in Monaghan through the Irish Civil War. “We were afraid of him,” he remembers.

Although he did not come from a cop family, O’Neill wanted to join the NYPD from an early age. The only police officer in his family was his uncle by marriage, Bill Reid, a happy man with great stories. “If anybody was my inspiration, it was him,” said O’Neill. “It just seemed like he loved life and really had a purpose.”

O’Neill joined the Transit Police in January of 1983. He was 25 at the time and had been working at an insurance company as a surety bond underwriter. “It was a good job working with good people, but this was in my heart and if I didn’t do it, I would regret it later in life,” he said.

He attended John Jay College of Criminal Justice, where he got a bachelor’s degree in government, and later a master’s degree in public administration.

Back in the 1980s, New York City was a different place. It was the era in which Gerald Ford infamously told the city to drop dead, if not in so many words. The subway was described as “the most dangerous place on Earth.” As Paul Theroux wrote in The New York Times in 1982, “It has been vandalized from end to end. It smells so hideous you want to put a clothespin on your nose, and it is so noisy the sound actually hurts. Is it dangerous? Ask anyone, and, without thinking, he will tell you there must be about two murders a day on the subway.”

It was an act of bravery to even venture down into the place, and James O’Neill was patrolling the night shift. As a Transit Police officer for 12 years, he would ride the subway by himself back and forth from 168th Street and Broadway at the tip of Manhattan, down to J Street in Brooklyn, from eight at night until four in the morning.

“Were there times that it felt a little dicey? Sure,” he said. “Was I afraid? I’m not sure.”

In 1995, when O’Neill was a lieutenant, the Transit and Housing Authority Police Departments merged with the NYPD. Once there, he continued moving up the ranks. “Every rank that I held, I wanted to do my best,” he said at his swearing-in ceremony as commissioner, choking up a bit, “and if that brought me further recognition, fine. But I didn’t do it to move up the ranks. I did it because that’s the way I’ve been taught by my mother to live my life.”

After the ceremony, his mother told reporters that she raised him “to be a sound and moral man, and to always do the right thing – and he has.”

O’Neill is unique in that he rose through the department to eventually become commissioner. A chief of department, the most senior uniformed position, had not been promoted to commissioner in over four decades, according to Thomas Reppetto, the author of NYPD: A City and Its Police.

He has held every rank in the NYPD except for detective (although he has been both a lieutenant and a chief in the detective bureau) and a two-star chief (because he jumped from one star to three stars).

Though his effective communication skills dealing with all types of people can be traced back to his time patrolling the subway trains and platforms, he considers his experience being a commanding officer to be the most helpful to him as commissioner. He commanded three precincts over six years: Central Park, the 25th Precinct in East Harlem, and the 44th in the Bronx, right around Yankee Stadium. “It’s almost like running a mini city,” he says. “It gives you the all-around experience; it gives you exposure to everything.”

O’Neill was commanding officer in East Harlem when the 9/11 attacks occurred. The police commissioner at the time, Bernard Kerik, had hosted a dinner the night before for all the commanding officers at the Museum of Natural History, so most of them were not in by eight o’clock in the morning. O’Neill got to his office in the 25th precinct shortly after the second tower fell.

Every precinct sent a sergeant and eight officers down to the World Trade Center that morning. “Thank God nobody from our precinct died,” said O’Neill, “but we had a couple people who were seriously injured. We didn’t know where they were all day.” He somberly named four men whom he knew who passed away that day: John D’Allara, Mike Curtin, John Coughlin, and Joe Vigiano.

“It was hard,” he said. “Still is.”

There are three things the commissioner is looking at when it comes to antiterrorism: the NYPD’s ability to investigate, their ability to prevent, and their ability to respond.

There is a Joint Terrorism Task Force comprised of 300 investigators from 56 agencies – 113 of them are New York City cops. Any threat that emerges from the stream is fully investigated, if not by the JTTF then by the NYPD’s Intelligence Bureau.

There are also NYPD detectives assigned to 14 different locations around the world, embedded with either the local, state, or federal police wherever they are stationed, sending intel back to the department in real time.

“We tabletop all the time, we run drills, and we make sure that we continue to talk to each other to ensure that nobody is keeping information to themselves,” he said.

The bombing in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan that injured 31 people occurred on September 17, 2016. O’Neill was legally, yet unofficially, sworn in as commissioner on September 16, the night before the attack, and officially sworn in at a ceremony the following Monday, September 19.

He was in the process of moving his things up to the commissioner’s office and had just left when he got the call. “At first I was thinking ‘I can’t believe this is happening,’” he recalls. “But then I knew just based on my experience that we would catch the guy who did it, and we did.”

They identified the suspect within 30 hours, and within 50 hours he was arrested.

O’Neill found out in the middle of his swearing-in ceremony that they had caught the perpetrator. A lieutenant walked over and handed him a note with the news, which he then discreetly showed to the new chief of department also about to be sworn in, Carlos Gomez, whose eyebrows shot up.

There was a scheduled press conference about the bombing directly following the ceremony. He recalls, “I actually asked John Miller right before the ceremony started, ‘Hey, can you do me a favor? Can you catch this guy before the end of the ceremony?’ And sure enough they did.”

The police commissioner does not wear a uniform, as it is a civilian position. Having donned the uniform every day for most of his 33-year career, O’Neill was very proud of it and sad to give it up. “If there is anything that was difficult about going from chief of department to police commissioner,” he said, “it was giving up the uniform.”

At the press conference announcing his appointment, he joked, “I’m really going to have to up my game when it comes to suits.”

Unlike previous commissioners, who had spent time in the private sector among New York’s social elite and came into the commissioner job wearing custom suits with ties from Hermès or Charvet, O’Neill is more sartorially modest. “His shirts and ties are more Marshalls or Century 21 than Armani or Canali,” ribbed John Miller, the Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence and Counterterrorism.

(He wore an Irish emerald green tie for our interview, which is good enough for me.)

After growing up in that little community within the capital of the world, O’Neill understood that the key to effective, cohesive policing is personal relationships and mutual trust between police officers and residents. It is about having that neighborhood cop who is looking out for the members of the community.

O’Neill first developed Neighborhood Policing, a comprehensive crime-fighting strategy based on improved communication and collaboration with the community members, as chief of patrol starting in June 2014, and as chief of department, he expanded it. It is structured to provide sector officers with off-radio time to engage with neighborhood residents, identify local problems, and work toward solutions.

Before Neighborhood Policing, the sectors were arbitrarily divided within the precincts. As part of Neighborhood Policing, the sectors have been redrawn to represent the natural neighborhoods.

Much of Neighborhood Policing depends on being able to make decisions at the rank of police officer, which is something that did not typically happen before. Now, when something is going on in a sector, if the officers don’t take care of it, it will still be there when they come back in the morning, so they have to come up with a creative solution in conjunction with the community. The officers take pride in this new responsibility. “It’s all about taking ownership, working together, and creating some unity here,” says O’Neill.

The final sector rollout was in October, making the strategy now operational in every residential neighborhood in the city. It is the largest, best funded, and best-staffed community policing initiative ever undertaken in the United States, and has fundamentally changed policing in New York City.

O’Neill knew from his vast experience as a police officer that the idea had potential, but he did not know how successful it was going to be in action. As it turns out, pretty successful: 2017 saw fewer than 300 homicides, the lowest number since the 1950s, and 2018 followed suit. (For comparison, there were 2245 homicides in 1990.) This past October, for the first time in more than 25 years, New York City went an entire three-day weekend period without a single shooting incident.

O’Neill attends a great deal of community meetings, so when he says, “Everywhere I go, I’m getting good feedback,” he means it.

Even with those impressive numbers and glowing feedback, O’Neill has still contracted with the RAND Corporation to produce an independent study to make sure that the program is building trust. “We know it’s keeping crime down,” he says, “but we have to make sure that this is what communities around New York City want.”

O’Neill says that the biggest challenge he faces right now is restoring the public’s trust in the NYPD. 2014 was a difficult time for law enforcement. Both of the grand jury decisions for the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the death-in-police-custody of Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, came in November and December of 2014, respectively.

There were protests every day. “The NYPD is used to handling protests,” said O’Neill, “but this time they were protesting us, and that culminated in the assassination of two of our police officers, Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, on December 20, 2014.”

“No matter what happens,” he said, “we have to make sure that we keep police officers motivated, and we continue to restore the trust that you need in order to effectively police anywhere, especially New York City.”

As a step toward building that trust in the NYPD, O’Neill announced in early February that he would support legislation to make more of the department’s disciplinary records public in the interest of transparency. “There are a lot of things we do well, but there are also a couple things we don’t do that well, and one of them is the transparency of our disciplinary system,” he said.

In an op-ed for the New York Daily News, O’Neill called for the reform of section 50-a of the New York State Civil Rights Law, which currently prohibits the disclosure of public employees’ personnel records, including the disciplinary records of cops. “For Neighborhood Policing to maximize its potential,” he wrote, “there must be mutual trust between the police and the public. And nothing builds trust like transparency and accountability.”

O’Neill owns three motorcycles, a Kawasaki Concours, a BMW Adventure, and a sport bike. “The BMW has hard steel cases in the back, so it’s pretty cool,” he says. He and a group made up of mostly active or retired cops ride all around the country. They have taken trips to Tennessee, Montana, Arkansas, Kentucky, West Virginia, and many trips to Maine.

Sometimes it’s six or seven guys, sometimes it’s as many as 19, like on their trip to Tennessee last year. His brothers, John and Hugh, tag along once in a while. “It’s a lot of fun,” says O’Neill. “They get a kick out of it, hanging out with my ‘cop friends,’ as they say.”

Without a doubt, New York City is in good hands with O’Neill, the sartorially modest New Yorker’s New Yorker who is continuing a long history of the Irish in the police department. When asked about this history, he pointed to a list up on the wall of all the NYPD commissioners and quipped, “You pick out the names that aren’t Irish!” ♦Maggie Holland

_______________

Click below to see Commissioner O’Neill’s remarks upon being inducted into the Irish America Hall of Fame.

Wish You The Best

Best Wishes Commissioner! Enjoy!

What a great guy. He must have been a real tough cop starting at Transit when he did ..that was the toughest job policing back then. You were on you own with radios sometimes ..NYC wa slucky to have him.