Colin Lacey reviews an eclectic mix of the latest albums on the Irish music scene.

Twice as prolific as most performers half his age, Van Morrison shows no sign of slowing down after more than 30 years in the business. How Long Has This Been Going on (Verve/Exile Productions) is Morrison’s third album in less than two years and follows last year’s critically acclaimed Days Like This? reckoned by many to be the Belfast musician’s best effort since the 1970s. Co-credited to longtime collaborator, Georgie Fame, How Long … forsakes the previous album’s pop/soul workouts and takes off in directions more often hinted at in live performances but only occasionally developed. Morrison has always been respectful of the influences and inspirations fueling his music, and here he pays tribute to artists like Mose Allison, Lester Young, Louis Jordan – even George and Ira Gershwin. With names like that it’s no surprise that jazz and jump blues standards from the days before rock’n’roll predominate, and How Long …, recorded last May at Ronnie Scott’s Club, the jazz Mecca of London, is sure to go down as Morrison’s `jazz album.’ But that shouldn’t scare off listeners wary of a musical form that, especially for beginners, can sometimes be difficult to appreciate. Morrison’s latest is an upbeat, finger-poppin’ treat, the sort of album you play when you need something to help put a pep in your step and a spring in your heels. Best of the fifteen selections are the protor’n’b of `Sack o’ Woe,’ Johnny Mercer’s `Blues in the Night (My Mama Done Told Me,’) and Morrison’s own `Moondance,’ one of three originals revamped and presented as jazz workouts. Fans of the genre may prefer to stick with the originals, but for Morrison’s followers How Long … will be relished as the work of an artist who refuses to accept the limits of operating within a single musical form.

Probably the most celebrated Irish singers in the world, The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem broke into the mainstream after an almost legendary appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1961, and for the next decade and beyond the group were at the forefront of a revival of Irish folk music in America and of American folk in general. The cheerfully title Ain’t it Grand Boys (Columbia) is an essential collection, a 2 CD set of live tracks, studio out-takes and lost performances that easily stands alongside the `official’ recordings released by the group and highlights the relaxed, robust, and – despite occasionally dark subject matter – joyous approach to performing that made the Clancys and Tommy Makem a breath of fresh air on the music scene. The collection ranges from non-Irish mainstream folk (Pete Seeger guests on a stirring 1961 performance of `This Land Is Your Land’) to clancy-Makem favorites like `Rising of the Moon,’ `Rosin the Bow,’ and `The Irish Rover,’ with a generous selection of lesser known gems, including an engaging `Children’s Medley’ and `American Medley’ filling out the 32 tracks. Columbia has also reissued the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem’s Irish Drinking Songs, a raucous album recorded with the Dubliners, along with their Luck of the Irish – is there (another)Clancy-Makem revival on the way?

At time of writing, Enya’s most recent release, The Memory of Trees (Warner) is causing quite a stir on the Billboard Top 100 charts, reaching No. 13 only weeks after its release, and placing the Donegal-born singer and musician in the same mega-selling league as mainstream stars Madonna, Michael Jackson and Bruce Springsteen. The new album, the first since 1991’s Grammy-winning Shepherd Moons, is a subtle, evocative collection that recreates the soundscapes and rhythms which have pushed the ex-Clannad vocalist into the vanguard of New Age music. Although Enya’s considered untrendy in some musical circles, that hasn’t stopped millions of fans from enjoying her quiet, impeccably textured sound: Shepherd Moons has spent 204 weeks on the Billboard charts; its predecessor, `Watermark,’ has been there on and off since its release in 1988. Two years in the making, it remains to be seen if The Memory of Trees can make it a three-peat for the publicity shy singer (Enya refuses to accommodate the media, and has never performed live), but the album has a depth and sophistication most artists only aspire to, and is likely to become a favorite among fans.

Musical families seem to flourish in Ireland (the Clancys, Clannad’s Ni Bhraonains, the Corrs, etc.), and although no single group can be named the First Family of Irish music, the eponymously-titled new release by the renowned Black Family (Blix Street Records) may in time come to be recognized as a weighty argument in favor of finally nominating someone to the title. Featuring siblings Michael, Shay, Martin, Frances and Mary, the album ranges across Irish and American folk and pop tunes, presenting both the familiar (`James Connolly,’ `The Bramble and the Rose’) alongside welcome surprises like Bob Dylan’s `Tomorrow Is A Long Time.’ Musically and technically accomplished and with a keen ear for precisely the right song selection, the Black Family has the added attraction of vocals from sisters Frances and Mary, two of Ireland’s most popular and important singers, and should continue soothing listeners’ ears through repeated playing. (Also available: The Black Family’s Time for Touching Home).

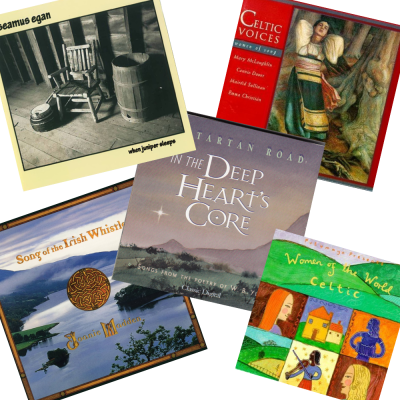

Mary Black also turns up on Women of the World: Celtic (Putumayo World Music), a strong, musically diverse album featuring contributions from some of the Celtic World’s leading female vocalists. Taking its cue from the successful compilation A Woman’s Heart, this 13-track collection reflects much of the variety and strength of the Irish musical scene in particular, and the Celtic musical scene in general. Featured along with Black are instantly recognizable names like Clannad’s Maire Brennan, Maire Breathnach, Altan’s Mairead Ni Mhaonaigh, and Maura O’Connell. Lesser-known names are also featured – Nancy McCallion’s fusion of Irish and Mexican folk is particularly intriguing – and the album, diversity notwithstanding (tracks range from delicate Clannadish sounds to the electrified folk of Fiona Joyce’s `Cry Over You’), maintains a coherency and consistency lacking in many a more ambitious project.

Four more women are featured on Celtic Voices: Women of Song (Narada), an album the liner notes suggest “make it easy to understand why so many people consider Celtic music to be the origional `soul’ music.” While the collection isn’t exactly the revelatory, it does include passionate performances by Irish artists Mary McLaughlin and Maireid Sullivan, the Isle of Man’s Emma Christian, and Connie Dover, an American born performer whose musical and ancestral roots run through Scots/Irish, English, Cherokee, Mexican and French. Four artists jostling for attention on one record can present problems, but the musical styles here complement each other and the album is a tasty sampler of how divergent Celtic music can be. Mary McLaughlin’s evocative `Sealwoman,’ inspired by the legends of the selkies, is a strong opener, and probably the album’s highlight, but also memorable are Connie Dover’s haunting `Cantus,’ Maireid Sullivan’s graceful version of the old chestnut `She Moved Through The Fair,’ and Emma Christian’s Manx lullaby, `Little Red Bird.’ Sampler albums like this work only when there’s enough material included to offer a rounded picture of each artist’s work. With three pieces each from McLaughlin and Sullivan and four from Dover and Christian, Celtic Voices offers a generous overview of four of the more talented Celtic performers working today.

Sticking with Celtic women, one album which is a must for traditional music fans is Joanie Madden’s new compilation, Song of the Irish Whistle (Hearts O’Space). Madden is rightly known as the Queen of the Whistle, and her new album portrays her at her percussion, Madden is a maestro, and for new listeners, this is a worthy introduction. While it can be moody in places, it has enough life and zest to balance it nicely. One of the better tracks, `The Immigrant,’ is likely to be played and replayed, while old favorites such as `Down by the Salley Gardens’ and `The Black Rose’ (or Roisin Dubh) take on new life under Madden’s talented hands. And check out `Flight of the Wild Geese.’ `Song of the Irish Whistle’ also encompasses the piano, harp and acoustic guitars, uileann pipes, accordion, violin, and the magnificent Eileen Ivers on the fiddle.

The album was produced and orchestrated by Joanie Madden, with the help of Brian Keane, Jerry O’Sullivan and Dave Anderson, among others. Don’t let this one slip through your fingers.

Also worth listening to are Narada’s Celtic Legacy and Celtic Odyssey, two albums of instrumentals that nicely supplement the `Women of Song’ collection.

One of the most surprising things about Kiltartan Road’s In The Deep Heart’s Core (Classical Digital) is that it’s taken so long for someone to come up with the idea of putting the poetry of W.B. Yeats to music. Another surprise – because messing with Yeats will inevitably attract hypercritical scrutiny – is that on the whole, it works. In The Deep Heart’s Core is an original song cycle fusing the verses and writings of Yeats with folk, classical, contemporary and traditional Irish musical styles. Essentially a recording of the first act of the similarly-named theatrical presentation produced at Chicago’s Bailiwick Repertory Theatre, the album began as a collaboration between composer and instrumentalist Joseph Daniel Sobol and vocalist Kathy Cowan, who met at the Yeats’ summer school in Sligo. Sobol and Cowan have gathered an impressive team of classical and traditional

musicians and approached the poetry (including such famous works as `The Fiddler of Dooney,’ `I Am of Ireland’ and `The Lake Isle of Inisfree’) with respect. But Kiltartan Road is rarely intimidated by Yeats’ material, and although purists may dismiss the notion of encountering the poet in such relatively strange territory, the album, which also includes printed lyrics, is an enjoyable and evocative journey through some of the best poetry Ireland has produced.

With his score for the film The Brothers McMullen, multi-instrumentalist Seamus Egan proved what many had claimed since the 26-year-old first appeared on the Irish American musical scene in the mid 1980s: here was a performer and composer with huge potential. Egan’s newest album When Juniper Sleeps (Shanachie) pushes the edge of what is considered Irish music – astute listeners will pick out influences from jazz, rock, world music and a whole lot more besides – and although the tunes and instrumentation are obviously Irish, Egan can’t be categorized and pinned down so easily. “The whole idea of what is traditional is a constantly evolving thing,” Egan has said, and his abroad, embracing approach makes for some beautiful performances here. But the Philadelphia-born, Irish-raised Egan, who plays flute, guitar, whistle, uileann pipes, banjo and bodhran among other instruments, never obscures melody with musical innovation for its own sake. Instead, he creates new surroundings in which traditionally-inflected melodies are given space to breathe and develop, often to quite stunning effect. The traditional `Mason’s Apron/My Love Is In America’ is a prime example of Egan’s approach: a hard-driving guitar tune that straddles jazz and traditional without ever losing sight of the original melody. Throughout his career Egan has brought new ideas and influences to his music: When Juniper Sleeps continues this tradition, and may be his finest album yet.

Listeners seeking music to soothe the savage beast would do well to check out Phil Coulter’s latest, Celtic Horizons. The biggest-selling Irish instrumentalist in the world, Coulter makes music as immediately identifiable as that of any artist working today. His fully-realized versions of Ireland’s greatest melodies have caught the attention of listeners throughout the world, and in the U.S., where his last album, American Tranquillity spent several weeks on the Billboard New Age charts, Coulter is a hugely popular and successful concert attraction. A soothing, dissonance-free quilt of orchestra, flute, guitar, synthesizer and more. Celtic Horizons strays barely at all from what his detractors may call the Coulter `formula,’ but that’s exactly why it works: part of the pleasure of listening to tracks like O’Carolan’s `Planxty Irwin,’ the traditional `Ar Eirinn,’ and Coulter’s own haunting compositions is that with even a single listen they become as comfortable and familiar as old friends. Recorded in Ballyvourney, County Cork in 1995, `Celtic Horizons’ includes eight Coulter originals, with the album’s centerpiece, the three-part `The Battle of Kinsale’ and `A Thiarna’, featuring the Coolea Choir, an Irish language group founded by Sean O’Riada, among the standouts. Coulter’s highly textured music certainly isn’t for everyone: in less striking moments, even some of the pieces included here sound like soundtrack music in search of a film, but `Celtic Horizons’ is undeniably sophisticated, and frequently quite beautiful.

It’s not exactly rock’n’roll, it’s not exactly orchestral, it’s not exactly a soundtrack: if it had been released by anyone else, Passengers’ Original Soundtracks 1 (Island) might have floundered without a genre to attach itself to. But Passengers are the New Age pioneer and record producer, Brian Eno, and Bono, the Edge, Larry Mullen and Adam Clayton of U2 along with a few high-profile guests, so Original Soundtracks 1, although not quite the album U2 fans might have expected, remains a project to be reckoned with. Inspired by a variety of films, including some not yet produced, Original Soundtracks flirts with ambient sounds, cocktail jazz, and even conventional rock. It’s a thoughtful, moody album that suggests U2’s music is about to burst through the boundaries dictated by mainstream rock music, and the album, although largely Eno’s show, augurs well for the next U2 album proper. If these are indeed soundtracks, the films promise to be as eerie, moody and dark, though not without beauty – think of Wim Wenders’ (a longtime U2 buddy) haunting `Wings of Desire’ – and the album, despite some sluggishness, has an intensity that would lend itself well to the demands of the big screen. `Your Blue Room’ and `A Different Kind of Blue’ typify the album’s poignancy, but it’s left to one of the greatest singers of our time, Luciano Pavarotti, to steal the show. His duet with Bono, `Miss Sarajevo,’ is an important a piece of work as U2 have produced, a song about tragedy that soars like a blessing. Does opera belong in rock music? After this, you’ll think it does.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March/April 1996 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply