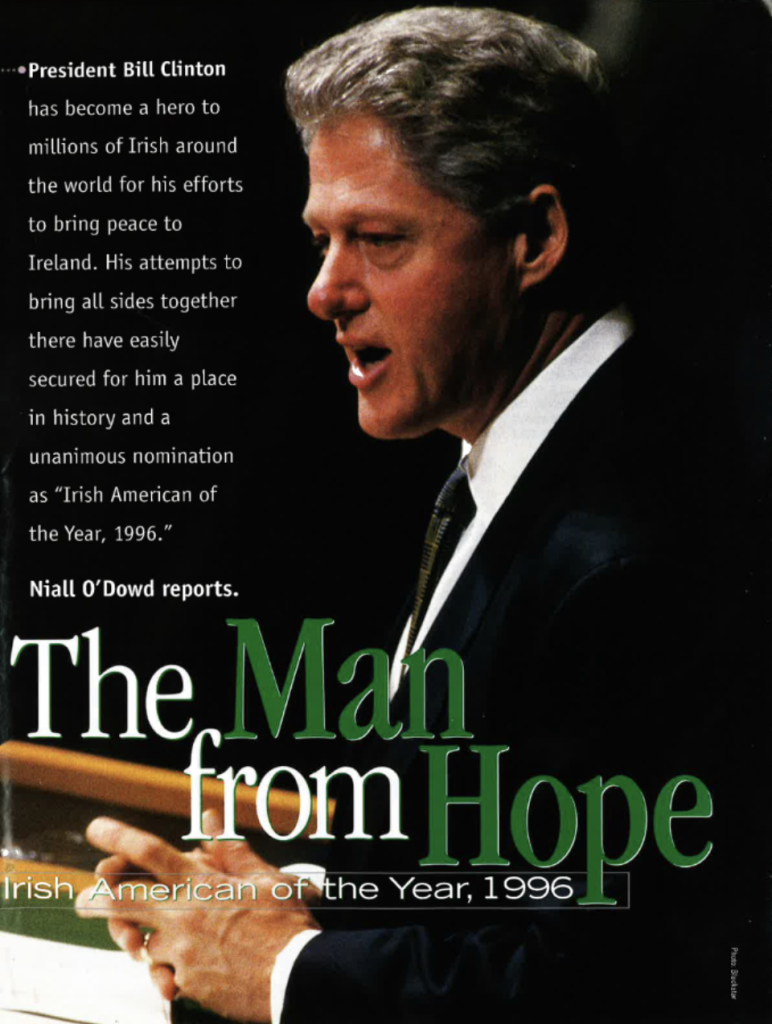

Irish American of the Year, 1996

It was an evening that dreams were made of, a crystal clear Belfast night, the winter air crackling with anticipation. On the sound stage adjacent to City Hall, Van Morrison was blasting out his There’ll Be Days Like This, the unofficial anthem of the peace. A huge and enthusiastic crowd, later numbered at 100,000 was rocking along to the music.

All day long the people of Belfast had streamed to this spot, mainly from Protestant and Catholic neighborhoods abutting the downtown area. They had filed through the narrow downtown canyons under the shadow of the tall buildings bedecked with American flags before collecting in their tens of thousands in the areas surrounding City Hall. As far as the eye could see, back up through the shopping malls, down the narrow sidestreets and along the pedestrian areas, the crowds had gathered.

Even Van Morrison was not holding their undivided attention. Every ten minutes or so a chant would pass through the crowd like a ripple. “We want Bill, We want Bill.”

The rumor had spread that he would play the sax with Van the Man, so every stranger arriving on stage was closely scrutinized. Several times the rumor ran that he was about to make his appearance, and the full-throated roars of the crowd were stilled only when it proved to be another false alarm.

On such a clear night every sound seemed magnified. The tolling of nearby church bells swelled in the evening air. The chants of the crowd carried like a relentless drumbeat, the strains of Van Morrison seemed to carry back even to the furthest regions of the crowd, who were cheering and stomping and waving plastic American flags thoughtfully supplied by the advance team. We all knew we were witnessing something special.

When the long-winded Lord Mayor of Belfast, Eric Smyth, Threatened to go on forever during the introduction, he was drowned out with chants of “We want Bill.” Quickly the mayor skipped to the end of his speech.

A few moments later the President and First Lady finally arrived at the podium. It had been a long day for him; his aides stated later that he was feeling tired and jet lagged. But the crowd lifted him, their extraordinary welcome lasting several minutes. A New York Times reporter later wrote that Clinton had that “suffused look of ecstasy” that politicians acquire before adoring crowds.

Clinton had earned the huge reception. As he had done throughout the day, he appealed over the heads of the politicians to the people themselves.

“The people want peace and the people will have peace,” he pronounced, pounding the podium for emphasis. The people promptly went wild.

There was one photograph in the following morning’s paper that held me. It was of a young man, tears streaming down his face, after he had shaken hands with Clinton. Not even the White House could have dared to believe that Clinton could capture such a wellspring of hope.

I was sitting near a Protestant community worker from the Shankill Road. She had a careworn face, like so many in Belfast, old beyond her 40 or so years, the impact of far too much worry and stress.

“We’ve had so little to celebrate in the past 25 years,” she told me. “When someone like the American President comes and shows he cares about us it means so much to all of us.” Her eyes seemed ready to tear up.

She told me that she and her husband had been to Dublin for the first time ever a few weeks before to see Riverdance, the Celtic dance spectacular. “It was brilliant,” she said, “and we’re going back soon again. We’d never ever have thought of going during the Troubles.”

They had stayed in a hotel on the road leading north to Belfast, she told me. Everyone had been so kind when they heard it was their first trip to Dublin.

“The bar manager sent over complimentary drinks. It was brilliant, so it was,” she said in the Belfast vernacular. “It wasn’t like another country.”

In front of her, a few seats to the left, sat Joe Cahill, a revered Republican figure who was once spared the hangman’s noose only by a last-second reprieve. Cahill’s journey to America on the eve of the IRA ceasefire had been a critical step in ensuring its success. Only he, it was reasoned, could convince Irish American hardliners that the new peace was worth a try.

“Did you think we’d see days like this?” I asked Cahill, paraphrasing the song.

“No, not like this,” he answered. “This has been a real high point for all of us. It is marvelous, really special, to see the President here.”

The sentiments they expressed from both sides of the divide were echoed everywhere throughout the two-day trip. The groundswell for peace and the evident goodwill for Clinton – who had, after all, taken risks for peace no American President ever had – was clear. Now he had come to their own beleaguered land, a place where some commentators had derided those who lived there as subhuman during the Troubles.

But they, like everyone else, just needed the acknowledgment that they are no better or worse than citizens in New York, Washington or London. Clinton may well have changed the atmosphere permanently in Northern Ireland. Even after the breakdown of the ceasefire there was total recognition that something had changed utterly in the wake of the Clinton visit, and that only the extremists now wanted to go back to the bombing and the killing.

Within two weeks of that breakdown hundreds of thousands of people had taken to the streets all over Ireland in singular endorsement of the President’s words: “The people want peace and the people will have peace.”

I had traveled to Ireland as part of a group of 40 or so Irish Americans. Many were not political soulmates of the President, but what they saw in Ireland would change forever their perception of the American presidency.

The office of President can often seem diminished in America because of the sharp edge of political debate and mudslinging. Now our group was seeing for the first time the impact of the American presidency abroad.

Everywhere President Clinton went in Ireland was a triumphal progress. From the huge crowds in Belfast, Derry and Dublin to the intimate moments such as those with Nobel Prize-winner Seamus Heaney at the U.S. Ambassador’s residence in Dublin, the President had the perfect pitch, understanding just where the line between American interference and positive involvement lay.

Don Keough is a former president of Coca-Cola and chairman of the board of Notre Dame. He is one of the great figures in Irish America, admired for his work in bringing to the attention of American businessmen the issue of investment in Ireland and for his work on behalf of Notre Dame. After our visit, he would return to Ireland with Warren Buffet and Bill Gates in tow for a spectacular get-together which he organized of some of the world’s leading businessmen.

“Clinton has made us proud as punch to be Americans on this trip,” Keough said, as we drove through Dublin the day after the Belfast visit. “You see those crowds on the streets with their American flags and you believe all over again the good that this country can do. We owe him a great deal of gratitude for that.

“The good that this man has done here will last long after him in Ireland,” he predicted. “He has lifted the spirits in a way I would have thought was impossible. No matter what happens, this is the beginning of a new era for American-Irish relations.”

Clinton had indeed ushered in a new era. For generations Irish Americans had tried to interest the President of the United States in the issue of Ireland. Because of the special relationship between Britain and the United states forged in the heat of the two World Wars and the continued existence of the cold war, their concerns were rarely listened to.

Yet there always remained an abiding sense among Irish Americans that the U.S. was the steeping giant, that if it were roused on the issue of Northern Ireland a whole new momentum could be delivered. That theory would be put to the test and pass under the Clinton presidency. The longest period of peace in the 25-year conflict occurred directly response to the involvement of the U.S. President.

Since assuming power in January 1993, President Clinton has set about building a new “special relationship” with Ireland, which in several important instances has eclipsed the historical tie with Britain when the two have come into conflict.

While the British, with their own self-interest at stake, have opposed the new line from the White House tooth and nail, bitterly fighting the visas for Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams and other leading Sinn Fein members and constantly trying to undercut Clinton in the British media, the attempt has failed as Clinton has seen the impact of his new line on Ireland work with spectacular success.

Several Irish Americans on the presidential trip saw the breakthrough as historic. Brian O’Dwyer the long-time Irish activist who is head of the Emerald Isle immigration center, saw a sea change as profound as any that ever occurred in Irish American politics.

“For generations we always felt we were locked out of the White House,” said O’Dwyer. “President Clinton has brought us in by the front door. As a result Irish American concerns will always have a higher profile, irrespective of who is in the White House in the future.”

Bruce Morrison, the former Connecticut congressman, a key player in the peace process whose Morrison visa bill allowed thousands of Irish to emigrate legally to the U.S., was equally complimentary. “Years ago we were lucky to meet the gatekeeper at the white House. This President has empowered Irish Americans, and we should not forget that in November.

“No President has ever invested his prestige and his concern for the people of Ireland and for the Troubles in Northern Ireland in the way Bill Clinton has,” Morrison added. “People can say what they want about him on other issues, but on Ireland he has been front and center from the time of his campaign through every day of his administration. I know that Bill Clinton’s concern about the situation in Ireland goes back a long way, and he can be counted on to do everything he can.”

The New York Times called the Clinton visit “the best two days of his presidency.” The President himself was clearly ecstatic that he struck such a chord with a country weary of war and desperate for peace. Clinton had made the Irish peace process his own. Indeed, without him it is unlikely it would have happened at all.

We can take no less an authority than the IRA for that. In a secret IRA memo revealed in the Sunday Tribune newspaper in Ireland on April 23, 1995 the reasons for the IRA ceasefire of August 31, 1994 were detailed. Among the three key reasons given was the support of President Clinton for the new peace process.

Once the peace process began, Clinton threw the full weight of the White House behind it. When the process was lagging, his White House Economic Conference on Ireland in May of 1995 provided an important boost. Throughout last year, his National Security Council staff headed by Anthony Lake and Nancy Soderberg continuously liaised between the differing parties, heading off several crises by their diplomacy. His own trip to Ireland was the culmination of that peace effort, and he has continued to give it priority even though the IRA ceasefire ended on February 9.

Following the breakdown the President pledged to help put the process back together, and he has been in frequent consultation since with the British and Irish leaders and with leading Irish American political figures such as Senators Edward Kennedy and Chris Dodd, as well as Jean Kennedy Smith, his ambassador in Ireland.

His economic envoy to Ireland, former Senator George Mitchell, was a key figure in seeking to resolve the arms decommissioning issue which bedeviled the talks between the British and Irish governments. Indeed, if the findings of the Mitchell Commission had been wholeheartedly accepted by the British government, there is strong evidence that the ceasefire would never have broken down.

Last May 25, President Bill Clinton became the first ever U.S. President to deliver a major speech on Irish issues when he addressed over 1,500 delegates to an unprecedented White House economic conference on Ireland.

The conference, held at the Sheraton Hotel in Washington over a three-day period, was the first time that any american President had committed his administration to that kind of direct economic and political involvement in the affairs of Ireland since the dawn of the American republic.

In addition to Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, Secretary of State Warren Christopher and Secretary of Commerce Ron Brown addressed the conference, which brought together Irish and American business and political leaders.

Those who attended got a taste of life in Ireland and Britain as it might be if peace ever takes hold. Loyalist paramilitary leaders sat drinking beer with Sinn Fein personnel, and bitter political opponents on both sides sat together in sessions debating the future of Northern Ireland. Community groups from both sides discussed how they could make joint applications for seed capital for projects that spanned the divide.

The future was there at that conference, the first time in history such an event had been held. Sir Patrick Mayhew, the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, met Gerry Adams for the first time ever; Irish Americans who have few opportunities to meet those from the Protestant tradition got to know their representatives in the most positive atmosphere possible.

The Van Morrison anthem, There’ll Be Days Like This, could have been written for the conference. Thanks to President Clinton, whose own Irish roots embrace both Catholic and Protestant antecedents, there surely will be many more.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March/April 1996 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply