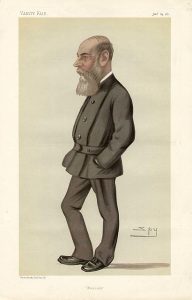

Captain Charles Boycott, an ordinary man though in possession of a repellent personality, has gone on to immortality due to his behavior in 19th Century Mayo.

Formerly an obscure officer in the British army, Captain Boycott was the land agent for an absentee landlord, Lord Erne, a position which afforded him a lush life on an estate outside the town of Ballinrobe. His lordship and his henchman collected hefty rents on tenants, which, when unpaid, resulted in violent evictions of large families.

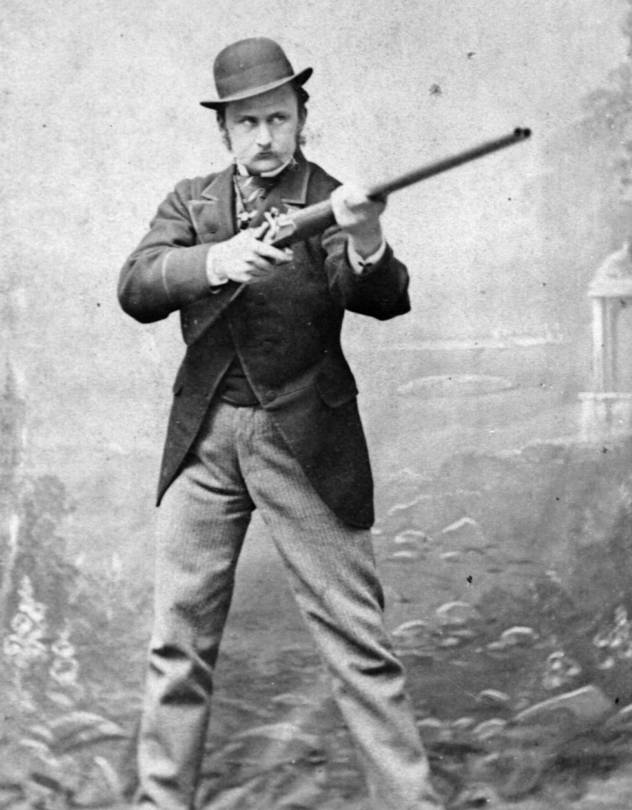

In 1880, Mayo was recovering from four years of poor harvests as Erne & Boycott were arranging a mass eviction of 11 families. Enter Ireland’s “uncrowned king” (and Joycean hero) Charles Stewart Parnell. Parnell and his Irish Land League manifested a plan for non-violent resistance: Ostracize the offender. They appointed Captain Boycott as Offender #1.

Tenant farmers and local peasantry stopped working his fields, and the estate staff, saving his jockey (Boycott was a fervid horseman), left en masse. The community came together to isolate Boycott: they wouldn’t speak to him or acknowledge his presence, saving boos and spitting on his shoes; local merchants wouldn’t sell him food; the young boy who delivered his mail sat down on the job, and the local blacksmith refused to shoe his horses, a cruel blow for one as horsey as the Captain. The local priest, Father O’Malley, suggested using the word “boycott” to describe the activity because “ostracize” was too complicated a word for the locals. “Let’s just say ‘boycott him,’” the cleric instructed a journalist. The expression soon traveled to Russia, where “Boikitturovat” became a popular political strategy. “Like a comet,” writer George Moore observed, “the word ‘boycott’ was everywhere.”

A desperate Boycott took his case to The London Times giving a litany of his suffering. Funds were raised to bring 50 farmers, Orangemen all, to help with the crops, then 900 men of the Royal Irish Constabulary arrived to protect the farmers who, according to one observer, “ate Boycott out of house and home.”

The dispirited Captain left for England and on to eponymous fame, going down in history as an ignoble servant of the Empire. The success of the Boycott-boycott inspired similar protests in Ireland; Parnell rose to greater prominence, enabling British PM Gladstone to pass the Land Act, which favored tenant farmers.

In modern history, boycotts have been used to great effect—to fight racism and anti-immigrant sentiment in the U.S., British Imperialism in India, apartheid in South Africa, and played a role in numerous Olympic squabbles. Over the years, talk show host Laura Ingraham, Bud Light, Disney, Nike, and even Oreos have been boycotted.

These days are fraught for many Americans who see Donald Trump and Elon Musk as dangerous to the US and its time-honored values. Perhaps that’s why embargos, sanctions and bans are on the rise. These 21st-century boycotts are designed to rally people and convince them they are not powerless and that there is something they can do.

A new organization, The People’s Union, had a successful economic boycott on February 28th and has scheduled more in the upcoming months. There’s an anti-Musk movement called teslatakedown.com that holds protests at Tesla dealerships with the call to arms, “sell your Teslas, dump your stock, join the picket lines.”

Sinn Féin, Ireland’s largest opposition party, is boycotting the traditional St. Patrick’s Day visit to the White House. They are protesting Donald Trump’s proposal to oust Gaza’s residents and rebuild the Strip as a “Riviera of the Middle East.” Who knows what will happen in these turbulent times? But we should remember that anything is possible. It certainly sounds unreal: 145 years ago the peasants of Ballinrobe, Co. Mayo made world history by ghosting a factotum of the British Empire at the height of its power. But it happened. ♦

Note: See here for a list of successful boycotts.

Leave a Reply