Liam Neeson’s name is synonymous with success. The big, handsome actor from Ballymena, Co. Antrim, has become one of the leading international stars of our time.

Nominated for an Academy Award for his role as Oskar Schindler in Schindler’s List, the veteran of some 35 movies has taken on the role of Ireland’s revolutionary leader Michael “The Big Fella” Collins, in a Neil Jordan movie, scheduled for release in October.

“There is a real renaissance that has been happening for some time in Ireland,” says Liam Neeson. “It’s great to feel so proud to be Irish. I’m not talking about just a sentimental feeling, but a real pride in where we come from, and out of all of the suffering of the Troubles, good things are blossoming in Ireland, North and South.”

In many ways, Liam Neeson himself embodies that renaissance. His Academy Award-nominated performance as Oskar Schindler in Schindler’s List came as part of an amazing decade in which he appeared in over 20 films. He played roles as diverse as the 18th-century Scottish Highlander Rob Roy, the contemporary art historian with whom both Mia Farrow and Judy Davis fall in love in Husbands and Wives, a Southern American sheriff in Leap of Faith with Steve Martin and Debra Winger, an Irish ghost is High Spirits, a Jesuit priest in The Mission and the doctor who protects a unique young woman played by Jodie Foster in Nell. Co-starring with Neeson in that film was his wife, Natasha Richardson, whom he had met at the Roundabout Theatre in New York, performing in Eugene O’neill’ Anna Christie. One critic described their work in that play as “the most intense exchange I have ever seen on a stage.

Last summer in Dublin, the couple’s first son was born. They named his Michael in honor of Michael Collins, the Irish revolutionary whom Neeson is playing in an upcoming Neil Jordan film.

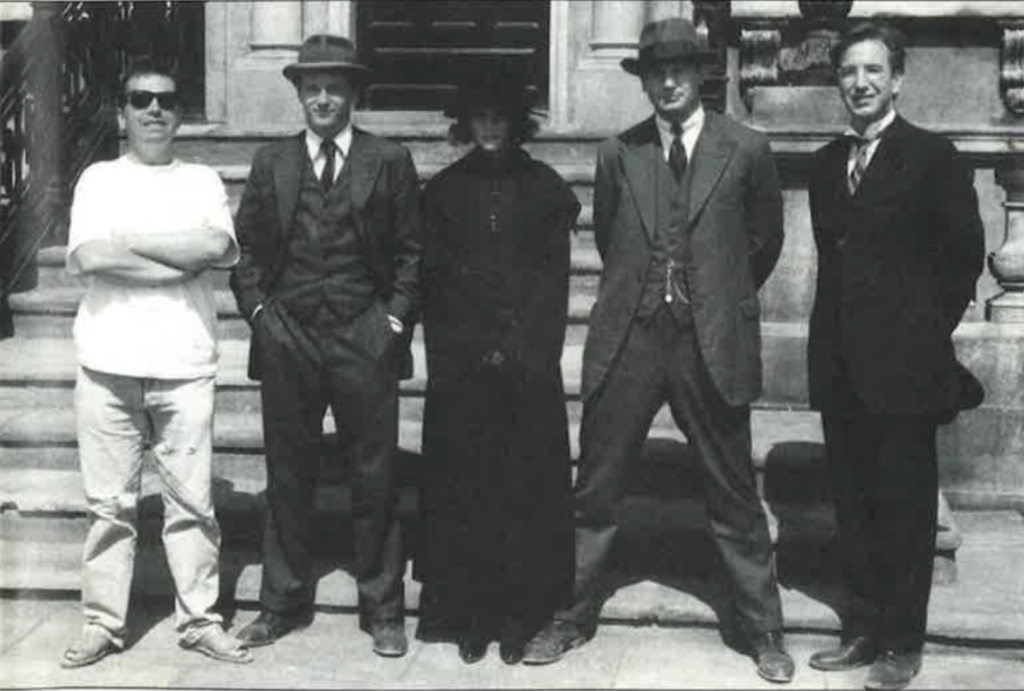

Neeson along with Aidan Quinn, Stephen Read and Julia Roberts worked with Jordan to tell one of Ireland’s most dramatics and tragic stories. For Neeson it was the “pinnacle of my career.”

He discussed the new film and the journey that has taken him from his home town of Ballymena in County Antrim to his current position as one of the world’s most respected actors during a recent interview with Irish America. He emphasized repeatedly how his success was rooted in “where I come from” and in people who never sacrificed their inner lives to outward violence.

“During the worst of the bombings and sectarian killings,” Neeson recalls, “there was always a drama festival going on in some little village hall. It was always supported by the people. I remember playing the Patrician Hall in Carrickmore, County Tyrone, both as an amateur and as a professional with Field Day. It was a big place, and the first time I went, I was surprised that at eight o’clock the hall was almost empty. But then I learned that the play would start at nine. That was so the cows could be milked and the farmers would have a chance to get washed up before coming to the play. Professionally I did Brian Friel’s Translations there with Stephen Rea, a Field Day production. In amateur days, I did Tennessee Williams’ Sweet Bird of Youth. I also played in Philadelphia, Here I Come.’

Neeson’s performance in Philadelphia, Here I Come won the Best Actor award at the festival held in Larne, county Antrim. At Carrickmore, another production of Philadelphia Here I Come took the prize. “It starred the McArdle twins, Kevin and Tommy, they were fantastic. They took the acting awards.”

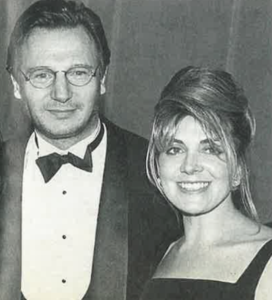

So in a sense, when I Liam Neeson accepted the American Ireland Fund’s heritage Award in Beverly Hills recently, he brought with him both those audiences who had first discovered him and comrades such as the McArdle twins. The Fund’s president, Loretta Brennan Glucksman, and the co-chairman of the dinner, producer Frank Price, presented the award in recognition of his professional achievements, but Neeson reached back 23 years to Ballymena for his acceptance speech, and told the following story to a glittering group that included two of his idols, Gregory Peck and Bob Hope:

“In 1972 I worked as a fork lift truck driver at a company called Murphy’s in my home town of Ballymena in Northern Ireland. There were two of us who were fork lift truck drivers. My partner, senior partner I should say, was like God. He was called Sam Hannaah. He’s the sort of man John Steinbeck would have loved, and would have written a book about. Stoic, very, very deep, a man of few words but a genius on a fork lift truck. I revered him. And he treated me as if I was a kind of piece of dust.

I was there just over a year and one day there was a break in the production line where Guinness and Harp were being bottled. Other man would take the bottled from the line and stick them onto pallets and the fork lift drivers would pick up the pallets and store them at the back of the factory. This particular day there was a lull. I’ll never forget it, Sam said to me, “Don’t stay here long, son. Get on with your life.” I was so stunned that he had actually said these pearls of wisdom to me. He didn’t look at me. He just said it straight out. And I thought O.K. I’ll tell him my innermost desires, which were my aspirations to become an actor. He listened to me, never looked at me, kept drawing on his cigarette.

“When I’d finished he took another pull and said, `You do it, son, you follow your dream because you never know, you might be the next Roy Rogers.'”

The dinner audience responded warmly and the entire evening became a celebration of that Northern spirit that enabled Liam Neeson to follow his dream. Neeson seemed to take a moment himself to marvel. “When I chose to follow my dream, the North of Ireland in 1972 was an incredibly violent year with unbelievable political turmoil. If anyone had told me then that 23 years later there would be a peace process occurring – or that I’d be on standing here tonight having made 35 films, received an Academy Award nomination, played my hero, Michael Collins, and in addition that I’d be married to a wonderful, beautiful woman, and would have a four-month-old Irish-American son, I’d have asked what Blarney Stone have you kissed? Neeson confided to Irish America that he had approached the dinner with a certain trepidation. “Before it happened, i felt terribly embarrassed, but when I got there. I had an incredible sense of pride. I knew that I was where I was because thousands before me had laid down the tracks. I was really honored to have Phil Coulter play at the dinner. I’ll never forget looking over during “The Town I Loved So Well” and seeing Bob Hope, I mean Bob Hope, with a big tear running down his cheek. The music really touched him. I saw Gregory Peck singing along to “Steal Away.”

“Then there was a realization that so many in the audience were descendants of those who had left Ireland during the Great Hunger.” In his speech, Neeson referred to this. “This year marks the 150the anniversary of Ireland’s Great Famine, when thousands of my fellow countrymen came to this country with only the cloths on their back and, wait till you hear this, an average life expectancy when they got here of six years. America has given a lot to the Irish. The Irish have given a lot to America as an immigrant population. We have worked hard, and thrived in industry, commerce, government and the arts. I am part of that heritage which the American Ireland Fund Actively works to preserve and nurture.”

Neeson said the Famine was very much on his mind during the making of Schindler’s List. “I spent a lot of time talking to the other actors in the film while we were staying together in the hotel. We agreed that there were many similarities between the Jewish people and the Irish people in their histories. Of course the Jewish people suffered in a much more dramatic and traumatic way, but there was a great deal of similarity in how we dealt with the suffering and oppression. For examples, we discovered similar rhythms in our music and our songs. After the movie came out, Steven Spielberg and I talked about how it made us realize the power of cinema and the responsibility one has. When a film maker deals with history, there’s a special accountability because of the power of those images which millions of people will see. Every scene in Schindler’s List actually took place. Obviously we took dramatic license with the chronological order, but with hand on heart, I know everything happened.”

Neil Jordan assumed a similar responsibility with the story of Michael Collins. Neeson said that Jordan had been working on the script for more than thirteen years. “All these years, Jordan was chiseling away at the script, tearing it down, improving it. A lot of people had talked about the subject before. John Huston had tried years ago to make a movie, and more recently Kevin Costner attempted it, but you needed the right script. Neil Jordan has told the story in such a way that you don’t have to have a degree in Irish history to follow it. Leaving aside one’s personal opinion about Michael Collins or Eamon de Valera, that period of Irish history in which it was literally brother against brother, uncle versus uncle, father against son, as it was in America’s Civil War, explains a lot about the fashioning of our country. David Geffen, God bless him, got Warner Brother to put up 25 million dollars, which, while not a huge budget for a Hollywood movie, it a lot of money by anyone’s standards. It shows a commitment to the concept and a confidence in Neil Jordan. We all took drastically reduced salaries to make sure that this movie was made. I had heard about Michael Collins since I was able to walk. He was a part of my life, and then eleven years ago, Neil asked me to play the part. It has taken up until this year for all of us to achieve that bit of clout to warrant David Geffen and Warner Brothers putting the money into it, so it’s been long road.”

A long road that had its own number of turnings. When Neeson first arrived in the United States, he ran into some old stereotypes about Irish people. “If I was playing an Irish character at some point, the director would come over for may be a cur away or a close-up, and would say, `No, let’s see, you’re Irish. Let’s get a glass of whiskey.’ I would say, `Excuse me, for a start I don’t drink spirits, and it’s wrong to think that every Irishman drinks.’ We should always guard against allowing ourselves to be stereotyped and at the same time, fight against making assumptions about others. It’s daily battle, because it’s unconscious. We internalize stereotypes about ourselves and others.”

Working with writers, directors and actors whose connections to Ireland are strong and immediate has helped to break that stereotyping and allow stories to be told that would never have been dealt with in the past. Michael Collins is one of those.

“All during these last year, Michael Collins has been on the back burner for me. I’ve been thinking about it and reading about him.” How does he feel about opening old wounds at a sensitive time in the history of Ireland? “I think this film can only help the peace process. It goes some way toward explaining what it is in human nature that ignites the passion and love for a country and how each person expresses that fire.”

When Liam Neeson thinks back to his early life, he sometimes shakes his head about how determined he was to pursue acting in the face of the Trouble. “I would hitchhike into Belfast after work on the fork life and I wouldn’t think anything of it. I was part of a group called the Clarence. We did the American play Johnny Belinda and Dylan Thomas’ Under Milkwood. On Monday, Wednesdays and Fridays, I would hitch into belfast for rehearsals because that’s what my life revolved around. I could have been short, anything could have happened. The innocence,” he marveled.

An even earlier outlet for his energy and a way of connecting to a wider world came for him through amateur boxing. At age nine he joined the All Saints Boxing Club in Ballymena, which was organized by Father Darrah, a 6’6″ amateur athlete himself. Neeson became an All-Ireland Junior Championship. One of his opponents in those days was Mick Tohill, now a staff member of prestigious Los Angeles law firm, who was credited as “Director of Moral” on Jim Sheridan’s In the Name of the Father. In those early days Tohill fought for a Belfast club called Dominic Savio nd traveled to Ballymena on Sundays to take on All Saints. “The church hall would be packed, “he remembers, “and it was murder – those country boys were tough.” He recalls the young Neeson in matches. “He would never step back! Ballymena men had that reputation – they would not give up. I was trying to be a boxer – I’d do a bit of dancing around the ring but they were fighters – straight on.” He fought as a bantam weight – 110 pounds. So did Neeson. “But then he sprouted up,” Tohill recalls.

Neeson remembers, “Mickey Tohill was six times All-Ireland Junior Champion, To my mind he was one of the greatest boxing artist Ireland ever produced. He would never tell you that, but we would just sit and watch him. He was like a performance artist – amazing.”

So Liam Neeson has much to draw on for the performances that so enthrall audiences and excite critics. He has played everywhere from parish halls to Broadway. And perhaps it’s because he gave so much of himself to his earlier theater groups, the Slemish Players, the Clarence, Field Day and the Lyric Players, that he is able to bring his fierce integrity to multi-million dollar Hollywood productions. He has played the great roles of the Irish theater and explored characters created by such American greats as John Steinbeck and Eugene O’Neill. But perhaps Michael Collins will be the role in which all of Liam Neeson’s past experiences will coalesce. The teenager hitching to Belfast, protected from the violence around him by his own passion and desire, will make his own profound contribution to the future and to the renaissance he has done so much to further.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January/February 1996 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply