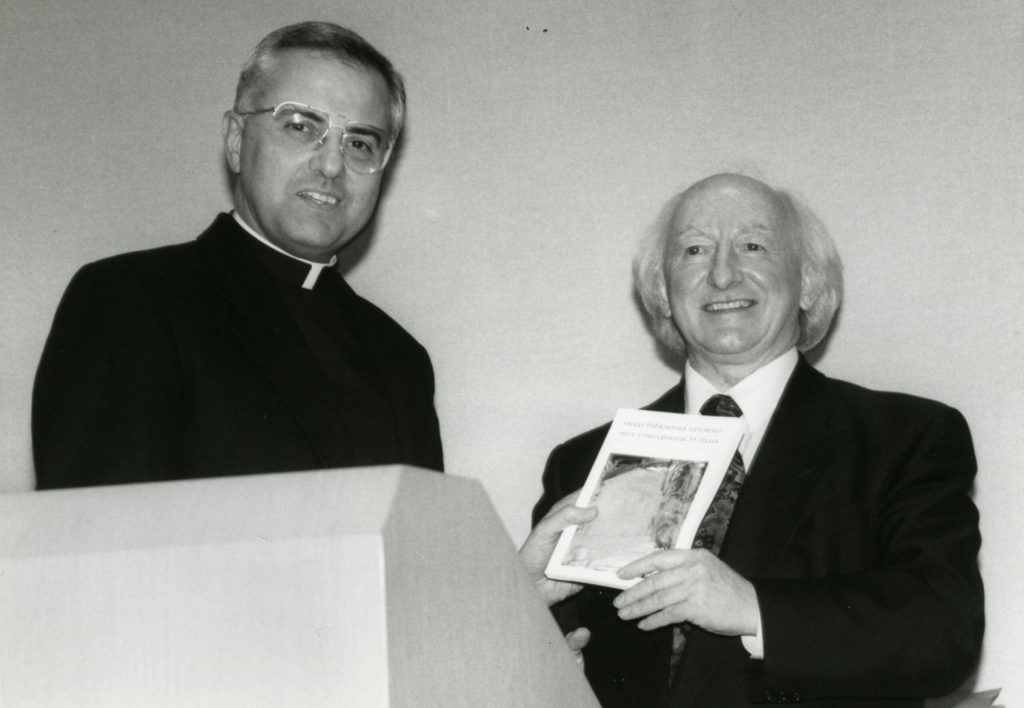

Colin Lacey talks to Michael D. Higgins (recently dubbed by British Vogue as the world’s grooviest arts minister) about the renaissance of the Irish film industry.

The Crying Game: My Left Foot; Braveheart; The Playboys; The Commitments; The Snapper; Circle of Friends; Window’s Peak; The Run of the Country; Into the West; Frankie Starlight – if you haven’t been closely watching behind-the-scenes developments in the film industry over the past few years, you could be forgiven for thinking Hollywood had packed it s bags and moved, lock, stock, and clapper-board, to Ireland.

There’s a fully-fledged renaissance underway in the Irish film industry, a boom that has been production levels surge almost 1,000 percent in less than four years, from a total of three features completed in 1991 to 29 major television and cinema productions in 1995 alone.

And remarkably, this intensive growth rate shows few signs of slowing down. Indeed, film production reached such a level of intensity last summer that Billboard magazine, the journal of record for entertainment industry insiders, reported that the schedules of almost every cinematographer, lighting expert, camera operator and film technician in the country were so overbooked producers were reduced to secretly poaching qualified crews from rival productions. “You used to be able to walk into Dublin on a Thursday and ask for the best crew and you had them by Friday morning,” said pioneer Irish film producer Morgan O’Sullivan. “Now you have to approach people a couple of months in advance and have a firm start date.”

But while available crews may be relatively scarce, the investment production companies are making in Ireland certainly aren’t. An independent analysis carried out by the Irish Business and Employers’ Federation in 1993 found that the sixteen television and feature productions completed that year contributed more than £50 million to the Irish economy. In 1994, Mel Gibson’s epic Braveheart alone brought at least pounds25 million in direct spending to the country, the largest figure ever spent by a single production on an Irish shoot, and between July 1994 and September 1995, productions with combined budgets of pounds185 million were scheduled for Irish-based filming, with an estimated pounds106 million of that being spent in Ireland.

Measured in terms of its financial influence on the Irish economy, in terms of its boost to direct and indirect employment, and even in terms of less calculable consequences like its effects on tourism and cultural prestige, the Irish film industry is clearly a material success. But how did a country whose presence on the international film scene before 1990 was largely marked by St. Patrick’s Day television reruns of Ryan’s Daughter, The Quiet Man, and Finian’s Rainbow emerge in the 1990s as an internationally popular, creatively significant, and financially lucrative center of film production?

If anyone figure can take credit for Ireland’s metamorphosis into a sort of mini-Hollywood, it is Michael D. Higgins, Labor T.D. for Galway, and current government Minister for the Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht. Higgins’ tax incentive program for the film industry – known informally as Section 35 – has radically altered the structure of movie financing in Ireland, and in turn, electrified the nature and level of film production in the country.

“People have come to know Section 35 because accountants and lawyers discuss it,” Higgins told Irish America from his office in Dail Eireann recently. “But the point is that it really works. The British Heritage Commission went to Los Angeles, Australia, and New Zealand to Study their industry structures, and they also looked at us. The principal recommendation of their report to the British government was to set up a scheme like Ireland’s Section 35. Also, when the European Parliament was debating the Audio Visual Committee report [in summer], it said that the one scheme that would in Europe was the Irish one.

“The rule in the film industry abroad is that when you are producing for five years at a certain level, you’re taken for real. You’re not a flash in the pan. The Irish film industry is not a flash in the pan. It has emerged and stabilized, and will continue to be stable into the future.

Described by one was as “Europe’s grooviest cabinet minister” (popular Irish rock band, the Sawdoctors, have even dedicated a song, “Rockin’ the Dail,” to him), Higgins, a former university lecturer, author of two books of poetry and founder member of Dublin’s Focus Theatre, was first elected to the Dail in 1981. A long time proponent of government-funded arts initiatives, his background and personal interest in the arts made him the natural choice to head the Department of Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht when it was founded in 1993.

The establishment of Department brought about a fresh emphasis on the promotion of artistic and cultural expression in Ireland, and Higgins, a quite-spoken West of Ireland native whose low-key deportment conceals vast reserves of energy and enthusiasm for the arts, indicated early that the expansion of production levels in the Irish film and television industry would be integral to his arts policy. One of his first acts as head of the new Department was to revamp existing laws governing investment and finance in the industry, essentially creating a framework to increase corporate and individual investment in Irish film and television production through a series of tax-relief measures.

“Section 35 is one step in a long set of measures,” Higgins said. “And it works. When I changed the scheme in 1993, we made twelve feature films. In 1994, we made fifteen films and twelve television series, In 1995, we will make somewhere between 25 and 35 feature and a number of series. [U.S. entertainment giant] Warner Bros. makes eighteen films a year. Section 35 has put us in the position whereby this country now makes more than Warner Bros..”

Prior to Higgins’ new initiatives, Section 35 had offered tax relief on film financing only to corporations, and limited investments to approximately pounds6000,000 every three years. The overhauled version significantly extends the program, raising the limit on investment by corporations to pounds1.05 million, and extending tax relief to individuals who can invest up to pounds 25,000 per annum. The investments are 100 percent tax-deductible, but Section 35 financing cannot account for more than 60 percent of a single film’s budget.

“The package now means most of the cost of production of a film can be raised by investors in the Irish tax system,” Higgins added “Does it cost the economy money? Of the 16 major television dramas and features that commenced in 1993, the cost to the exchequer was pounds6.1 million. The return, by was of Value Added Tax nd thing like that, was pounds7.7 million. In other words, without taking in any of the secondary effects, there is going to be a surplus on Section 35 projects.”

Higgins’ initiative also re-established the Irish Film Board, a production and finance resource for filmmakers which had lain dormant since being de-funded due to government cuts in 1987, and specified that all films certified for Section 35 financing hire and train young film graduates and film makers for the duration of the production. According to Higgins, this has provided up-and-coming film makers with a huge boost: of the 29 movies scheduled for shooting in 1995, at least six were by first-time Irish directors.

But despite the obvious advantages it has brought to the industry, Section 35 has been criticized as an open invitation for foreign film makers to come to Ireland, receive the budget-conserving tax breaks other countries don’t offer, and shoot a film with little regard to its cultural and artistic relevance. Reviewing Braveheart – the story of 13th century Scottish nationalist William Wallace, and one of Section 35’s biggest successes – influential Irish Times critic Fintan O’Toole remarked on the film’s fudging of historical fact with audience – friendly fiction and it s use of Irish defense forces as unpaid extras, and asked rhetorically, “Is this what an Irish film industry is for?”

Perhaps in anticipation of such grievances, Higgins instituted a rigorous certification process for producers applying for Section 35 tax relief. As well as the financial and training requirements, films must also conform to tough artistic, cultural, and social specifications.

“I’m fascinated with the discussion of what makes an Irish film,” Higgins said, perhaps a little wearied by the lingering argument and its implied criticisms of his efforts. “But I’m afraid I hold a rather peasant view of that. I believe it’s better to discuss what is an Irish film when Irish film crews are working rather than unemployed. Now, we do have a lot of business and I can turn to and deal with these sort of issues.

“[The Irish film industry] is, of course, about money and jobs, but it isn’t about that only. As Minister for broadcasting, I say this issue is one where citizenship is tested. Citizens have the right to use the technology to carry their stories, their expressions, their imaginations, their madnesses and their sanities. The alternative is to see a population as a consumer of other people’s images, so the issue is a cultural as well as an economic one. Section 35 is about training and producing people to use this art form, this cultural expression, in a way that will make statements about themselves.

“I have certified about 29 films for production in 1995. Of that 29, eight are totally Irish, twelve are predominantly Irish, and six are by first-time Irish directors who started off with the Irish Film Board. The point is that film making is an industry and an art, and what Section 35 really means is that we’re using Irish creativity and Irish workers to create a future for Irish film activity.”

Higgins is convinced that Section 35 will continue to attract investment into Ireland; by the end of 1995, he had already certified up to twenty films for production under Section 35 in 1996, with more to follow. And the success of the program can hardly be doubted – barely a month goes by without a major international release that owes at least something to his Department, and even critics feel assured that Ireland’s place in the international film making community is assure certainly in the short term.

With government across the globe – and in the U.S. in particular – backing off from involvement in the arts, Ireland provides an examples to the rest of the world of how the balance between commerce, art, and government sponsorship can be maintained.

And according to Higgins, Ireland’s politician mogul, the industry is still only finding its feet.

“The next phase would be to go for an alternative distribution system,” he said. “For the Irish film industry, the best is yet to come.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January/February 1996 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply