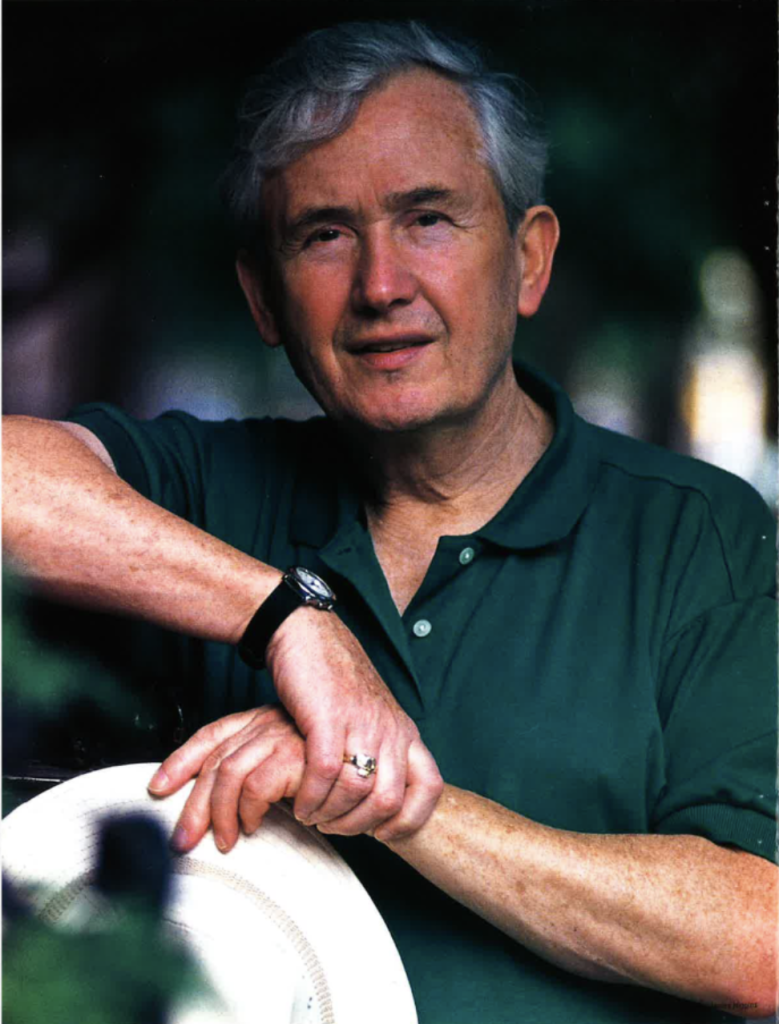

Frank McCourt has gone from retired New York City high school teacher to 66-year-old international celebrity in a matter of months. Almost a year after the publication of Angela’s Ashes, McCourt tells Brian Rohan “it’s been lovely, thank you, but I wouldn’t mind a bit of peace and quiet, either….”

Frank McCourt sits in the back room of the Old Town tavern, acting not at all like a man who has just won the Pulitzer Prize. The white-haired 66-year-old twirls his spoon and pokes at a damp teabag staining the wood before him, assuming the same deadpan expression — what he calls the “hangdog” — whether addressing the waitress or delivering yet another remarkable story. Like the one about his internationally celebrated best-seller, Angela’s Ashes.

“Oh it’ll die away soon enough,” he sniffs, deadly serious. “My 15 minutes of fame are about up.”

He said something similar in mid-December, when Angela’s Ashes first hit Number One on the New York Times bestseller list. “It’ll drop like a stone after Christmas,” he predicted at the time. “As soon as everyone buys a present for mammy, it’ll be done.”

Six months later, the book is in the top three nearly every week. Since publication late last summer, Angela’s Ashes has spent more than 40 consecutive weeks — and counting — among the Top 20, nine of them at Number One. It has been sold to 13 countries and nearly as many languages; has been bought by Hollywood for a sum in the high six figures; has landed its author on the couches of Conan O’Brien, Rosie O’Donnell, Bill Maher, Charlie Rose and Tom Snyder (three times).

Just the other night, hundreds violated fire department regulations at another saloon, Rocky Sullivan’s on Lexington Avenue, where McCourt gave a reading for charity: the medical bills of a recently-deceased local actor and friend, Chris O’Neill. The event had been sold out for weeks, at $15 a ticket, yet dozens stood outside, just to get a glimpse. One woman tried to get past the bouncer with a hundred dollar bill; she was turned away.

Despite all this, McCourt still speaks as if he’ll have to resume teaching in the New York City public schools, something he did for 30 years. Fifteen minutes into his first cup of tea on this rainy Manhattan afternoon, he is proven wrong again, this time by a kid of about twenty, wearing blue denims and a nosering.

“Dude, can I get your autograph?,” says the kid.

McCourt swivels his head up to the young fan, pausing for a moment on the nosering. The kid is asked how he enjoyed the book.

“Oh I didn’t read it,” says the kid. “But I saw you on TV the other day, and you really kicked ass on Katie Couric.”

McCourt, his attention focused on a ball-point pen and a cocktail napkin, barely raises an eyebrow. “Really?,” he responds. “I don’t recall kicking anything on Katie Couric the other day.”

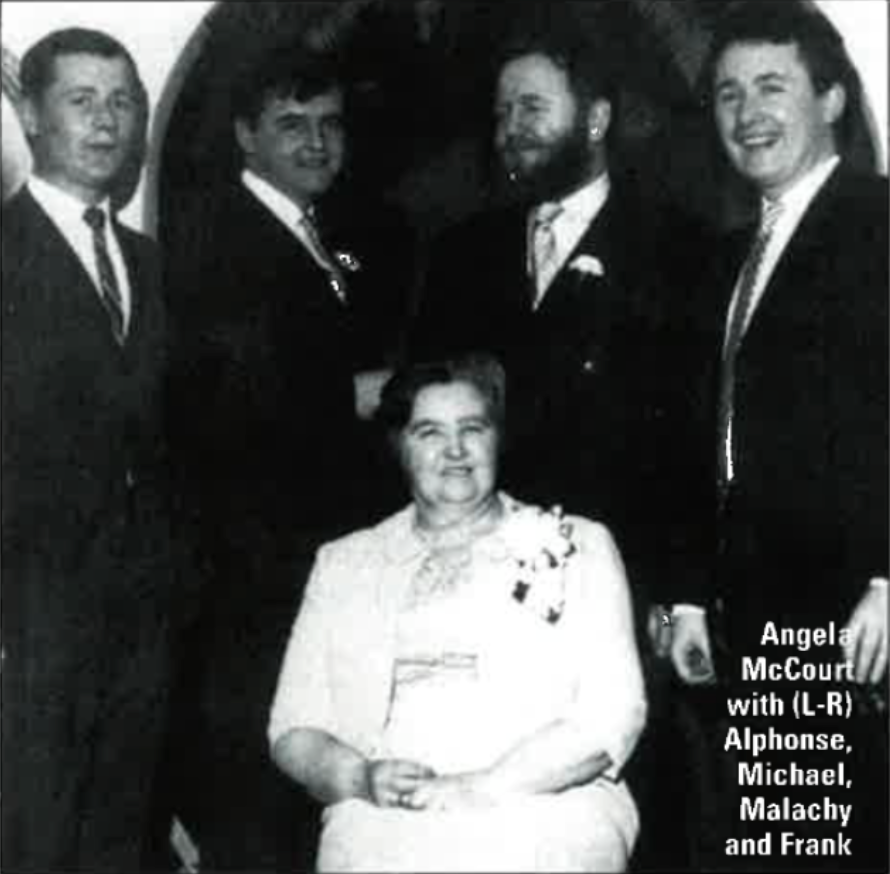

IT’s been that kind of year for Frank McCourt: women stopping him in airports; men fighting to buy him a drink. As told in Angela’s Ashes, this was not always the way for Frank, the grey-faced and black-humored eldest of Angela McCourt’s seven children.

Born in Brooklyn in 1930, Frank was reared by the fiercely determined Limerick native Angela (of the book’s title) and her Belfast-born husband, the alcoholic and work-shy Malachy McCourt. Near-destitute, the family relocated to the slums of Limerick City. Angela’s Ashes juggles tragedy and comedy in a style reminiscent of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. When Mr. McCourt drinks the dole money and Angela has to beg lot the family’s Christmas dinner the huge. dripping head of a pig the boys in the lane are merciless as young Frankie struggles to carry it home:

Hey Christy, do you know how to ate a pig’s head?

No I don’t, Paddy.

Grab him by the ears an’ chew the face offa him.

Hey Paddy, do you know the only part of the pig the McCourts don’t ate?

No I don’t, Christy.

The only part they don’t ate is the oink.

Frank managed to save the fare for a boat to America by the age of 19, the point at which Angela’s Ashes finishes. He arrived in New York City by ship, on the eve of the Korean War. The young Irish kid was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent on a troop ship to Hamburg, West Germany, where he recalls a gruff-voiced drill sergeant handed out the assignments:

“McCourt!”

“Yes sir.”

“McCourt, what’s the first thing you do with a dog?”

“Er…Feed him, sir.”

“No, McCourt. The first thing you do with it dog is let him know who’s master.”

With that, Frank found out that he would be spending the Korean War training German shepherds.

“They figured, hey — he’s Irish, so it must be animals or agriculture,” McCourt recalls. “But of course I was from the slums of Limerick, I knew absolutely nothing about animals. They gave me six weeks of training and then they gave me my own dog. Then I became a trainer of dog trainers. Surrounded by dogs. And to this day, I hate the things.”

McCourt returned to New York where he joined a generation of young men suddenly able to change its situation through the G.I. Bill.

“Every day of my life I say, `Thank Christ the Chinese invaded Korea,'” he says. “It was a terrible thing to do on the Koreans, but it was one of the best things that ever happened to Frank McCourt.”

The Army vet went to New York University and read voraciously: novels, histories, plays, poetry — whatever he got his hands on. He supported himself by working at Merchants’ Refrigeration in Lower Manhattan.

“On a hot, horrible day you’d be taking these sides of beef off refrigerator trucks from Chicago out into New York and 95 degrees and into the deep freeze room, then back out into New York and 95 degrees and back in the refrigerator trucks, and so on. From an early point, I realized I was always going to be too scrawny, so I kept reading.”

McCourt qualified as a teacher and began work at a tough, public vocational school on Staten Island.

“That was in the days of Blackboard Jungle,” says McCourt, referring to the 1959 film about rebellious and gang-crazy schoolkids and the post-war phenomenon of ‘teenagers.’ “They were poor kids who were told from an early age they were stupid, so they were sent to vocational school. Naturally, I decided to teach them Shakespeare.

“The other teachers thought I was crazy. ‘Shakespeare?’ they’d say, ‘They’ll kill ya.’ All they had in the school were these dreary old novels, books like Silas Marner. The dirty old man book, the kids called it.”

McCourt bought a box of $1.65 Shakespeare collections — with his own money — and handed them out to a classroom of thirty-five skeptics. McCourt says the students were soon converted.

“They loved it,” says McCourt. “There was no analysis or any of that, we just started reading out loud. We got to Hamlet and they’d heard of it, they knew it was this famous or important play. They’d start reading these soliloquies in a big, theatrical voice, you know, `To be or not to be….’ I’d say No, no no — didja ever worry about life or didja ever feel depressed? That’s the way it is — just talk it. They began to understand what Shakespeare was up to.”

McCourt soon became noticed for his unconventional way of teaching kids how to read and write: heavy on drama, with kids singing the words to Mother Goose rhymes and ancient Irish folk songs which McCourt learned from his father.

“We used to read The Brothers Grimm and a lot of children’s stuff. In high schools, real literature is often used as nothing more than a threat,” says McCourt. “You do something bad, you have to memorize a poem. I figured out you had to make children superior to the material, so you use children’s material. Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen and Irish songs — I’d bring in my harmonica or tapes and records of Liam Clancy and Tommy Makem doing the `Rocky Road to Dublin.’

“They loved it, especially the gruesome old Irish sing-songs like `Weel-a-weel-a-waulya,'” says McCourt, breaking out into song. “Stuck the knife in the baby’s head/Weela weela wallya….”

“The other teachers would walk by and hear 35 kids singing some old Irish tune and they wouldn’t know what to think,” said McCourt. “But you see, I was trying to ease the kids into poetry in a sneaky way. What were they going to do? Say you can’t sing songs or teach grammar in a vocational school on Staten Island because the kids are dummies and they’ll kill ya?”

By the time McCourt ended up teaching at the prestigious Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan, he’d earned a reputation as an unconventional and challenging teacher who demanded his students write what they know, in straight, simple language.

“I had one young fella who liked to write high-flown prose,” McCourt recalls. “You know, grand, purple prose. I would say, Simplify it. Cut it out. Say what you have to say and get it over with. He couldn’t understand, and I don’t think I ever got through to him. He thought he was being elegant. I said just tell your story, tell it straight. But no, he’d say, Henry James…..

“I’d say, F— – Henry James,” he says. “`Once upon a time’ is good enough for you right now.”

It was a lesson McCourt had been learning all along in his own writing. For many years, McCourt says he carried the stories of his family’s poverty and alcoholism like a shameful secret, something not to be told in his new world as a teacher and man of words in America.

“When I was in NYU I used to tell people that my father had been a postman,” McCourt recalls. “That was the highest I could aspire to. I was ashamed like my mother was that we had to eat pig’s head for Christmas dinner or that we had no shoes. And of course, a lot of it was me in NYU with all these beautiful young American girls. I couldn’t exactly tell them that we ate the head of a pig, could I?”

An early incarnation of Angela’s Ashes was written while McCourt was at NYU in the Fifties: a short story detailing the crushing poverty of the author’s youth. McCourt says his teacher loved it, but McCourt was too embarrassed to fulfill the teacher’s request that he read it aloud to the class.

Eventually, McCourt was joined in New York by Malachy, the younger brother who has outshined him since birth, when Frank was just 13 months old. Whereas Frank was thin and quiet, Malachy was round and jovial, with red cheeks and a personality that expands to fill any room. Malachy is a bounding, singing barroom performer, yet Frank’s humor is understated and dark. He takes a certain pride in the fact that Angela’s Ashes, for all its humor, does not have a single exclamation point.

Malachy took to New York like a young Brendan Behan: he was known to New York bartenders as the man with all the stories and songs and to midwestern housewives as the bartender on `Ryan’s Hope.’ The 65-year-old West Side resident still works on soaps such as `All My Children’ and `One Life to Live.’ “I’m usually the bartender or the priest,” Malachy jokes. “Sometimes they let me branch out and I play an Irish terrorist.”

Frank moonlighted from his teacher’s position with a nighttime career as “Malachy’s brother.” They went together to literary haunts and political events, with Malachy doing all the talking and Frank hanging back.

“I never thought of Frank as a writer,” says Pete Hamill, the novelist and New York newspaper veteran, also a Brooklyn-Irish kid raised on the G.I. Bill. “I knew he was a teacher, and of course I knew he was Malachy’s brother, and he used to come down to the Lion’s Head, but it never occurred to me that Frank would be the one to write such a great book.”

Mary Breasted, a longtime friend and author who socialized in the same circles, said that when Frank did open up, the room was often astounded.

“Malachy always would bring him to these parties and functions at the Irish Consulate,” recalls Breasted. “One day, [Frank] opened his mouth at the Consul General’s house. He started telling these stories and everyone just stood, their mouths wide open.”

Both the McCourts were told by people to put all the stories down in one place, and so Frank wound up in the 1970s in Malachy’s kitchen on West 93rd Street, putting together what would eventually become a two-man show.

“I said to him, you’re telling your stories at the bar and I’m telling mine to the kids — let’s sit down and put them together,” Frank recalls. “We made a list of these anecdotes and stories and decided Right, there it is.

“We never had a script, we just had lists of stories,” Frank remembers, laughing. “It was such a bulls — t venture.”

The brothers staged their one-man show — A Couple of Blaguards — at a small East Side bar called Billy Monk’s.

“I would tell one of the stories on the list, and then Malachy would tell one,” says Frank. “He’d stand up and I’d sit down, I’d stand up then he’d sit down, we would sing a song or two, and we were charging people ten dollars for this. We did it for about four weeks.”

A Couple of Blaguards, which Frank and Malachy performed in various incarnations over the course of almost two decades, featured the same type of hilarious tragedy that would one day be found in Angela’s Ashes. Frank was the ultimate `straight’ man, the Bud Abbott to Malachy’s Lou Costello. At the opening night in Billy Monk’s, Angela McCourt, who was now an old woman and had since moved back to New York from Limerick, stood up in the middle of the show and cried out, “It wasn’t like that at all! That’s all a pack a’ lies. A pack a’ lies.”

“It was that shame all over again,” recalls Frank. “That notion that you couldn’t talk about these things, that it was something to be embarrassed of. She stood up and started shouting at the stage in the middle of the show.”

The show was received well by a handful of critics, including one from the Daily News which praised “the greatest talker ever to come out of Ireland.” And his brother.

News of the show traveled, and in 1984, a producer called. This prompted Frank to do what he had never done before — type out a script. The show ran in the now-closed Village Gate on Bleecker Street and traveled to Chicago, where it ran for six months.

“I used to fly out after last class every Friday afternoon, on the 3:20 People’s Express from Newark,” says Frank. “They had a stand in for me on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday. Malachy didn’t like the stand in’s delivery or his timing, so he used to be so glad to see me — two shows on Friday, two on Saturday and another on Sunday, then I’d run for the last flight back to New York. I didn’t know where I was half the time.”

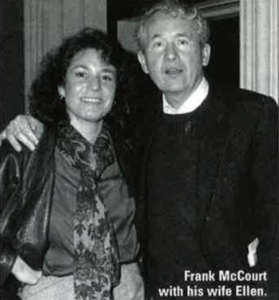

All the while, the germ of a book was growing in Frank’s head, someplace where he could get all his stories — or at least some of them — down in one place. But there was always class in the morning, and parties and plays with Malachy at night. Frank married twice — “the second one lasted about five minutes,” he recalls — and fathered a daughter, now in her twenties. Angela McCourt died in 1981. (Malachy, the father, disappeared when Frank was still a child).

The success of Angela’s Ashes has prompted an army of friends and strangers to tell McCourt that he should have done it a lot sooner.

“Of course I should have done it a long time ago,” says McCourt. “I should’ve cut back on the teaching, I should’ve gotten it down, but I don’t know if I could have. I wasn’t ready, I think. Or maybe I was.”

Hamill says that McCourt obviously had to shed a few demons in order to find the peace of mind to write a book like Angela’s Ashes.

“There was a lot of that silence in Irish childhoods of mine and Frank’s generation,” he says. “The things not spoken of. The scandals. There’s some things that, when you’re a writer, you could not write about until you gain the proper distance, the proper perspective.”

Jim Dwyer, another New York newspaperman who won a Pulitzer for journalism in 1994, agrees. “Irish America has always aspired to respectability,” says Dwyer. “They were hated when they arrived here in the 19th Century, and they’ve tried since then to become the establishment, to become respectable. Now, we’re more mature and settled enough to open up the trunk a little bit, where all the nasty bits of our history are kept. Frank’s book does that masterfully.”

“I suppose I could have done it earlier,” says McCourt. “I suppose I had the talent, but I didn’t have the balls.”

Ultimately, though, it seems as if Frank’s third and current marriage in 1995 — to New York publicist Ellen Frey — provided the necessary peace of mind to write Angela’s Ashes. On the first morning of the couple’s honeymoon, at a country cottage along a river in Pennsylvania, Frank woke up, went outside and started writing.

“It all just flew out of me,” he recalls. “It just came so naturally. I wrote the first page of Angela’s Ashes that day pretty much exactly as it appears in the finished book.”

“He just wrote and wrote and what he was writing was so obviously wonderful,” says Ellen. “Here I was thinking I was getting married to a recently-retired high school teacher and suddenly he’s an author.”

McCourt asked a friend — the above-mentioned Mary Breasted — to take a look at the first 80 or so pages.

“I told him it was wonderful, and would he mind if I showed it to a friend who was an agent,” Breasted recalls. “I brought it to Molly Friedrich and she said to me, `Okay, it’s a memoir by an unknown writer set in nineteen thirties and forties Ireland — Tell him not to expect me to get back to him too soon.’

“That was on a Friday,” said Breasted. “On Monday Molly called me back and said she couldn’t put it down, and asked where was this guy McCourt, she needed to talk to him right away.”

The rest, of course, is history. The book landed on the desk of Nan Graham at Scribners, and Frank was signed up for a major release.

“I didn’t even have a full book and next thing you know I had an agent,” says Frank, shaking his head. “Next thing I have a publisher. Who’s given me a six figure advance. Even though I’ve only written half a book. Next thing I’m being recognized in the airport.”

ONE million copies of Angela’s Ashes have been sold by Scribners in the North American market alone. The book is still on bestseller lists around the world, and there’s no telling when it will end. McCourt says he’s still somewhat baffled by its appeal.

“I think it’s got an old-fashioned appeal, maybe because of the child’s voice that is the narrative; certain words, certain details,” he theorizes. “People seem to think they know me from the book, and they like that I guess. A woman stopped me the other day and said, I read your book, I know all about you now. They like the connection with the writer, with the person.”

After several awards including the National Book Critics Circle Award and an honorary chair at Limerick University, news of the Pulitzer — awarded in early June — rounded off McCourt’s wonderful year.

“Jesus — the Pulitzer,” he says. “I was lying awake this morning and I said it to myself: Pulitzer Prize winner. Pulitzer Prize winner. Ha ha ha ha. It sounds so ridiculous. There are so many great writers who’ve been writing for years who never won a Pulitzer Prize, some of them can barely make a living. I write one book and I’m a Pulitzer Prize winner. Ha!”

Frank has been signed up by Scribners for a sequel, and has become an international celebrity. Earlier this year, a TV crew flew him and his three surviving brothers — Malachy, Alfie and Eugene, who all live in the U.S. — back to Limerick for a documentary. In late June, Scribners are throwing a huge congratulatory party for McCourt on the East River, at the Water Club.

As for Malachy, he has suddenly become “Frank’s brother,” and jokes good-naturedly about his newfound obscurity. He too is at work on a book — also his first — a memoir about his days carousing in New York.

Frank, meanwhile, tries to find time to write and he and Ellen are in the process of finding a place to live other than their crowded one-bedroom. McCourt says he keeps his head down to its proper size with the customary self-deprecating humor. He tells how the Angela’s Ashes film rights have been bought by Hollywood (for a sum rumored to be near one million dollars), and the book is being turned into a screenplay by the screenwriter who last adapted Henry James’ Portrait of a Lady.

“I think she’s re-naming Angela’s Ashes `Portrait of a Scabby-Eyed Kid from Limerick,'” he says. “Coming soon to a theater near you.”

With the way things are going for McCourt, it should be a huge success no matter what the title.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply