The recent worldwide commercial and critical success of Celtic arts would lead the casual observer or consumer in the US to innocently assume that the Irish and the Scots have always been amicable, if not kissing, Celtic cousins. The theory is, as one Scots Gaelic historian said to me in Glasgow recently, “aren’t we all the same people?” To a large extent that’s true and sectarianism between the Scots-born Irish Catholics and native Scots-Protestants has declined significantly in recent years. The unprecedented worldwide success of Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, although far from historically accurate, did hint at Scotland’s pre-Reformation `Catholic roots,’ indeed, the sight of Scots hero William Wallace blessing himself with the sign of the cross before battle became in itself a minor talking-point in Scotland. The film also clearly showed how Scotland and Ireland were at one time military allies — a point some people would have trouble believing. But it’s also true to say the two countries are separated, as much as linked, by their shared histories.

“In the city of Glasgow in the 1790’s, there was at one time, only something like thirty-nine recorded Irish Catholics resident in the city…but at the same time there were forty-two registered anti-Irish Catholic societies.”

I’m talking on a transatlantic call to Rennie McOwan, a respected, award-winning writer, historian and broadcaster who lives in Stirling, Scotland. We are discussing the rocky path that Irish immigrants have taken since they fast arrived in Scotland in the early 19th century. Rennie reflects on my community’s difficult roots:

“The spread of Irish migration in different parts of Scotland caused alarm bells to ring, and organizations like the Church of Scotland produced resolutions mentioning `this Catholic menace’ in a way that you would never do nowadays…They were feared because, like all migrant communities, they had to accept the lower paid jobs, sometimes employers would take on Irish at a lower rate than they paid native Scots, and there was certainly friction with Highlanders who were also dispossessed. And of course there was a post-Reformation hangover about Catholicism. But I think that the absorption of the Irish into Scottish society has been what one prominent historian called ‘one of the glories of Scottish history’.”

To many this might all seem to be the stuff of dull, dusty history books. To me however it’s part of an ongoing internal debate that I’ve been having for years and I’m not quite sure if I agree one-hundred per cent with Rennie McOwan’s opinion about the “absorption of the Irish [being] one of the glories of Scottish history.” I was born and brought up in Scotland by an Irish mother and a second-generation Irish father. My accent is as unmistakably Scots as Billy Connolly or Sean Connery, yet I proudly hold an Irish passport and claim the right of citizenship to that country. I regard Scotland as my home; yet, paradoxically, I don’t feel as at home there as I do in Ireland. As a child I happily spent summers in County Offaly in Ireland where my family comes from and where, in 1996, my mother and father and one of my five sisters returned to. Yet I also have a sentimental attachment to the Irish-influenced West of Scotland where I grew up. I once wrote that I am neither McFish nor O’Fowl — only at home travelling between the two countries or, where I am just now, the U.S.A. It’s an odd, although by American standards not unusual, predicament to be in.

Scottish snapshot number one: I’m talking to a colleague, another professional journalist from Glasgow, who tells me that a quality-broadsheet newspaper in Glasgow had, until relatively recently, a strict rule about job applications for reporters. The personnel department in the newspaper always divided the applications into three piles: the rejections; the interviewees; and the ‘don’t-bother-to-even-ask’ pile. The last contained all the applications from Irish Catholic journalists.

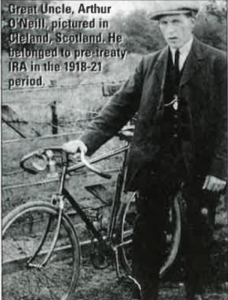

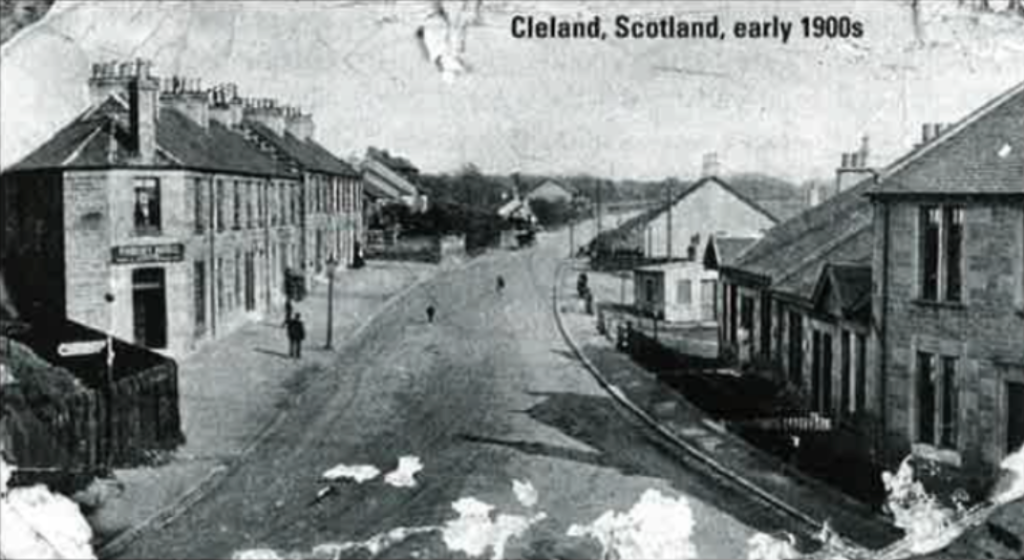

The community I grew up in Scotland wasn’t really Scottish. We never did things which were truly Scottish — I knew no one who played the bagpipes, wore kilts, ate haggis or read the poetry of Robert Bums. It was a gloomy little mining village called Cleland that lay forty miles from Edinburgh and fifteen miles from Glasgow. It once had thousands of Irish immigrant families living in it; nearly all the men worked in its numerous coal mines or in the steelworks nearby — all dislocated souls who lived for their work and for the chance to scrape any kind of living. Many were simply the Irish emigrés who hadn’t been physically fit or financially able enough to make it to America — so they’d left pre- and post-Famine Ireland for the nearest country — Scotland.

They had all taken the leap of emigrating from Ireland, yet on arrival in another country they’d immediately begun setting up all the familiar trappings of the place they’d just left. It was a cliché-ridden, typical tale. And the first place they all headed for when they gathered some cash together was back home, to Ireland.

On St. Patrick’s Day when I was a child we were lined up, marched to mass and told to sing in our thick Scottish accents:

“Hail Glorious St. Patrick, Dear Saint of Our Isle!”

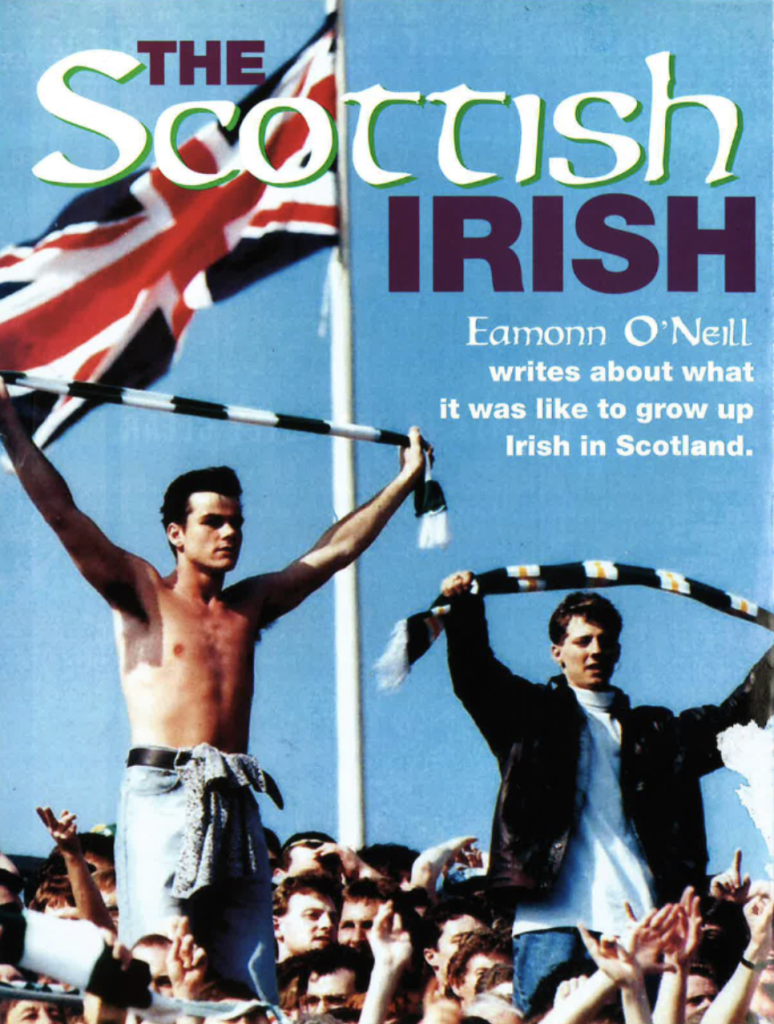

Even at nine years old I knew only too well that St. Patrick was not held dearly by the majority of Scots and that he certainly wasn’t regarded as `ours’ by many people in the UK. On Saturdays half the male population of the village gathered in huddled groups, decked out in green and white, while they waited in the foggy drizzle for the buses to arrive that would take them to the Celtic soccer matches in Glasgow. Going to one of these soccer games was for most people the one and only time they ever saw an Irish tricolor flying. This was the place they could feel part of something bigger, the place they could raise their voices and, however unlikely the location or inappropriate the reason, they could sing The Soldier’s Song and not feel out of place. As writer Colm Toibín says about the Celtic supporters he spent the day with in Glasgow during his travels for his ground-breaking book The Sign of the Cross: “They were having a great time: their team had won, they were with their tribe, and there was hope still.”

In truth I believe I went to about six Celtic matches in my entire life. My Irish mother disliked me attending them and I wasn’t encouraged to go regularly. The jingoistic, overt and at times antagonistic Irishness displayed by many second-generation Scots-born Irish families drove her up the wall. She believed they didn’t really understand what being Irish was all about; how could they, since many of them had never left Scotland to visit Ireland in their lives. She was unusual because she held hopes of assimilating and being accepted into the native population; she had loved Ireland but she was equally grateful for the chance to live and work in a new country. Others, however, blamed all their misfortune on Scotland and believed they were not welcome there. Many simply felt like second-class citizens. The only chance they had to peacefully celebrate their common heritage was at Celtic matches — for that reason the game of soccer took on a higher meaning. And the country that their forefathers came from, although only forty-minutes away by plane, also took on a greater significance. Ireland to them became a utopia, a place to escape back to in their dreams and barstool fantasies. Many had never been back to the land of their forebears; indeed in many ways they didn’t have to cross the Irish sea to get their `fix’ — they simply put their Irish music on, went to the local AOH meeting and jumped around on the terraces at a Celtic game to feel part of a wider community. Our family never went in for too much of that. When I was about eight years old, however. I can recall visiting a neighbor downstairs from us. Their name was O’Kane and I stood in silence in their house looking at the rows of pictures on the walls: Irish freedom fighters. poets. Celtic players and the slain Kennedy brothers. Beneath my feet was the pope’s face weaved into a lurid rug. The man who lived there had never been in Ireland in his life but that certainly didn’t discourage him from claiming Ireland as home.

Small Irish communities like this were in many ways, culturally speaking, completely self-sufficient. I remember coming home at lunchtime from school and hearing Gay Byrne on the radio, I listened to Gaelic Football matches from Croke Park in Dublin and heard the commentator mention players who had the same name I did. My mother baked Irish soda bread every week and we all received Irish guests from across the water every so often. We lived, more or less, in a green tinted cocoon.

Outside of our little world the country called `Scotland’ carried on as normal. We rarely ventured into it and when we did we made sure it was in numbers and done very quickly. People would ask us where we came from and when we’d tell them that or our names, they’d answer, “Well we don’t need to ask what foot you kick with.” This was a subtle way of saying they knew we were Irish-Catholics and, therefore, we should know our place. I never knew anyone who had actually visited the Scottish highlands on holiday — the North, despite its beautiful scenery and mountains, was considered a vast, thorny wilderness of Protestantism which would be unwelcome to us. I knew no one who even wore tartan scarves. When Scotland reached the World Cup soccer finals nobody paid much attention because the rumor was that Irish-Catholic Celtic players were never picked for the team anyway.

The only people I knew who had traveled anywhere to speak of were two guys who had gone from the village to Lisbon in Portugal, to see Celtic in the European Cup Final in 1967. One had disappeared never to be seen again, whilst the other returned bedraggled and shocked with horror stories of being abandoned by drunken friends on scorching highways with no money or water. Thirty years later he still talks about that trip with such heartfelt, wide-eyed and sincere fear that one would believe it only happened last week. Small wonder no one went very far. The only place people I knew felt safe going to was back home to Ireland. Every summer our large family piled into cars or onto buses and trains to head for the ferry terminals and the boats that crossed the Irish sea. I still recall as a child being held up by my father to see `Paddy’s Milestone,’ a small rock-island that lies halfway between the Western Scottish coast and Ireland. It became a symbolic milestone, telling the ex-pat Irish that they were either halfway to their adopted country or halfway home to Ireland.

The unspoken, underlying reality which many places like Cleland felt was simply the fact that we all knew we were the children of incomers. Scotland is a predominantly Protestant country and its roots are entangled in the roots of the present-day problems in Northern Ireland. Many Irish incomers were from the Northern Donegal area and they knew only too well about the awful tensions and troubles that sectarianism could give birth to. Everyone knows that the first British-sponsored plantation settlers in what is now Northern Ireland were from predominantly Scots Protestant families. Few in the U.S., however, realize the consequences for Scots of that small piece of history. There is still a significant, although probably less than it was in the ’70s and ’80s, amount of sympathy and underground support for the loyalist cause in Scotland. Every year in Scotland there are massive Orange Walks, just like there are in Northern Ireland, where thousands of marchers walk through city streets with bands, banners and hundreds of hangers-on following them. I grew up with the golden role never to be in a town or city near the middle of July, I wasn’t taught this rule because my family were bigoted — on the contrary — it was simply because my mother and father feared for my safety. The huge, often drunk crowds that followed the more orderly marchers didn’t look as if they were keen on peaceful diplomacy. They were merely warming up, practising for the `real’ trip to Belfast the following week. In some ways it was all harmless — I’ve read of claims that the Orange Order and the AOH in some West of Scotland towns even pooled resources and swapped flutes and drums for their respective marches. In other ways it was scary and confusing, and the image of the benign, hearty and welcoming Scots people went flying out the window when, as a Catholic with an obvious Irish name, you found yourself stuck on a public bus in the middle of a loud and aggressive crowd following the Orange Walk only a few miles from where you called home. I recall sitting there, barely suppressing a panic attack, sweating buckets and quickly examining myself to make sure I didn’t have any green clothes on. I was scared to death. In later years as a professional journalist I was horrified to feel exactly the same emotions of panic and fear wash over me when I watched a parade go by in Glasgow. I told my American wife that I knew how a U.S.-born African-American must feel when they see the Ku Klux Klan parading. Once the fear worms its way into your belly as a child it’s very hard to get rid of it. You are made to feel second-class, second-best and afraid.

In the early 1980s when unemployment was high and tension was stretched, I remember an Orange Walk being arranged to come through my home village of Cleland. This hadn’t happened, said my father, since the 1940s. Crowds gathered, like some mob scenes from a film about revolutionary France in 1789, with loud voices proclaiming that no such anti-Catholic organization would be allowed to parade in our peaceful village. In any event, the march did go ahead, albeit at seven o’clock in the morning when everyone was in their beds. I stood at my bedroom window in my underwear watching incredulously as two dozen bleary-eyed and very nervous Orangemen played `The Sash’ at double time and marched like the Foreign Legion in the clear early morning sun for about three hundred yards before jumping on a bus and driving like hell. It was mildly funny at the time. I didn’t know, however, what would happen later.

That night the local mob gathered at the village cross armed with bricks and stones and any other missiles they could lay their hands on, waiting for the marchers to drive back through the village. When the buses arrived, the locals set upon them like a pack of hounds on a fox. I saw one man with blood streaming down his face after a brick smashed through his window. This was the awful reality of an extreme, and to be fair, rare pocket of sectarianism in Scotland. It was a throwback to an earlier, more violent age when sectarian riots happened with sickening regularity. The parade should never have been allowed to happen in the first place. The people of Cleland who responded with violence were, of course, wrong but they feared that the event would become a regular fixture since other villages in the area with substantial numbers of Irish Catholics had become the annual venues for huge Orange Walks that attracted thousands from all over Scotland and Northern Ireland. That walk in my village was, thank God, a one-off affair. It brought out the worst in people. I’m glad it has never happened again and I have to say sectarian violence is, thankfully, now relatively scarce in Scotland.

Tradionally speaking, the oldest flashpoint for the sectarian problem in Scotland was the soccer match between Celtic and their arch-rivals the Glasgow Rangers. Rangers have always had a traditionally staunch Protestant following. Celtic’s working-class Irish-Catholic roots lend the frequent matches between these two teams an added air of palpable tension. The club was founded by a Catholic, Brother Walfrid, a member of the Marist religious order, as a charitable organization, its main goals being to raise money for free dinners, poor relief and to distribute second-hand clothing among the huge numbers of poor that crowded into the stinking slums of Glasgow’s East End. The club became a limited liability company in 1897 and happily signed players no matter what their religion was, although given its location in the heart of the city’s Irish Catholic population, Catholics inevitably outnumbered Protestants. Both teams have made attempts to disown their respective `extreme’ supporters — Celtic recently made headlines by asking its supporters not to sing Irish Republican songs at games and Rangers reversed its old unwritten but well-known policy of not signing Roman Catholics in the late ’80s — but the unspoken reality is that change will not happen overnight. As a Russian reporter once said to me about old Communists suddenly acquiring democratic tendencies in the wake of Perostroika: “You can’t wash a black dog white.” Many however believe that the frustration vented at these games by both sides of supporters serve as a safety-valve that allows the pressure to be aired without violent consequences. The realities of big business in soccer also now mean that the days of small Scots-Irish Catholic clubs not giving a player a game unless he had a letter of recommendation from his parish priest are long gone. A Celtic player is as likely to speak French or Dutch now as he is to be from Donegal.

Scottish snapshot number two: I’m talking to a telecommunications engineer who works for a leading Scottish media company. He’s fixing some wires for my computer in my office. I chat to him for a while, indeed I quite like him, he’s a good worker and a nice guy. I can truthfully say I’ve never given a second thought to his religion or political leanings. However, I’ve heard from a colleague that he has a framed picture of Lee Harvey Oswald on his office wall and I’m genuinely quite curious as to his reasoning for this, so I gently ask him about it. He sheepishly tells me that he’s sick of seeing photos of JFK and RFK on display everywhere and that it’s about time “we had a photo of Oswald up since he got one of yours [an Irish Catholic] didn’t he?'”

“There has been a change from the fortress mentality in the Irish community in Scotland,” says Rennie McOwan, who has edited the Scottish Catholic Observer in the past. “The Irish Catholic newspapers were in the past newspapers from the garrison. The situation was like the incoming Catholic cowboys on the frontier firing over the stockade at the whooping native Protestant Indians who were attacking. That was the atmosphere and there was prejudice against Irish and Scottish Catholics, there’s no doubt about that. There was legislation against them — as late as 1924 it was against the law for Catholics to hold a procession in public. Then we had separated schooling. In fairness to the bishops of the time we didn’t want separated schooling but the organization of schooling in Scotland was dominated by the Presbyterian ethos and by the Church of Scotland. The Catholic Bishops began their own schools and the Catholic parents paid twice — once for schools their children could not go to, so-called state-schools, and once for Catholic schools. Of course that situation has changed in our lifetime, and we’re hearing a lot of talk about the fusion of the schools long-term but gradually the community has become less tribal.”

The success of the 1982 Papal visit to Scotland certainly bolstered any insecurities that Scottish Catholics may have had about their identity. The children of Irish Catholic incomers were able to feel equals, some would say for the first time, in their own country. Many were heartened by the olive branch which the then Moderator of the Church of Scotland, Professor John McIntyre, extended to the Catholic Pontiff, Pope John Paul II, when he visited Edinburgh. The enduring image of that visit will always be the sight of the head of the Roman Catholic Church standing with the head of the Church of Scotland beneath the statue of John Knox, the man who brought Protestantism to Scotland. It was one of the more hopeful images in the thorny relationship between the two religions.

Although it was an uphill struggle, one area that the Irish Scots did take a full part in from day one was organized labor and politics in general. In Professor Tom Gallagher’s respected book about the Irish in Scotland, Glasgow: The Uneasy Peace, he details the roots of the Irish communitys involvement in the Scottish political scene:

“Where the Irish left behind casual open-air labor and became part of the factory workforce, they were affected by the class consciousness which grew up in the enclosed world of the factory. In 1836, employers who gave evidence before the select committee on the Irish poor, testified that Irish workers were more prone to rebellion and insubordination than English workers. The Irish were `the talkers and ringleaders on all occasions,’ the `most difficult to handle,’ having a `command of words’ by which they often misled English workers.”

This involvement manifested itself in the present century in Scotland with large numbers of the Irish community becoming active in and actively supporting the traditionally left-wing union-supported and union-funded British Labor Party. The fallout from this firm link between the Irish working-class immigrants and the Labor Party in Scotland has been recent accusations that a so-called `Irish Mafia’ is very much still at work in the 1990s in the Labor Party in some areas of the West of Scotland. Opponents of this allegation argue that it is actually Conservative Party mischief-making which is nothing more than a cynical attempt to split the working-class vote on sectarian grounds. Scottish working-class Protestants have, for the most part, united along class lines with their Catholic counterparts and voted for the left-wing Labor Party. At various times, however, anecdotal evidence suggests that since the Conservative Party is the traditional party of the Union of Northern Ireland and Great Britain, many Scottish Protestants have switched their vote to the Tories (Conservatives) for this reason or as a protest vote against perceived Irish Catholic bias in the much stronger Labor Party. The Irish influence in other areas of the Scottish political scene has been less contentious. The Scottish National Party, for example, which has traditionally proposed breaking away from the rest of the UK, now points to the success which Ireland enjoys with its policy of independence within the European Union. It believes that Scotland could benefit from pursuing such a policy and contends that the Scottish economy could, like Ireland’s, flourish if it were allowed to stand on its own two feet in Brussels. The stately welcome enjoyed by Irish President Mary Robinson during her highly successful 1996 trip to Glasgow also underlined the respect in which she is held in Scotland. Many Scots Nationalists point to her high international standing as an example of how a Scots President could function if Scotland broke away from the rest of the UK and in the process, ditched the Queen as its head of state.

Scottish snapshot number three: I’m talking to a leading Scottish poet and playwright; she grew up only three miles from the village where I lived. We exchange stories about our respective childhoods. She speaks in the `old Scots’ language about her upbringing and then listens intently as I talk of the Irish Catholic world I grew up in with its symbolism of priests, crucifixes, patriots, slain American politicians, Celtic matches and Popes. She says she’s never heard of this world, she knows nothing of it. I grew up within sight of her home yet we came from entirely different places, both emotionally and culturally. An awkward embarrassed silence follows our exchange.

The implications of this divide reach further than the two or three miles that separated my village and the village where the well-known poet and playwright lived. As an adult I’ve noticed how the arts in Scotland rarely, if ever, reflect the significant Irish Catholic population’s contribution to Scots culture. Surely, if only by virtue of our mere existence, we must have contributed something to the Scottish arts scene? There has been recent talk of a renaissance in Scots writing — James Kelman, Irvine Welsh to name but two well-known authors who were pictured smiling in a group photograph next to an article about this subject in the New Yorker recently — yet none of these new writers come from an Irish Catholic background which is surprising given the disproportionate contribution Irish writing has made to the world of literature over the centuries. No standard Scots works in print ever mention in any detail my community’s existence — we seem to be absent from the arts in Scotland all together. Anyone examining the works produced over the last hundred years would think nobody ever arrived in Scotland from Ireland at all. Then again, to the best of my knowledge, no one from my community has made a significant impact with a published or produced work which deals with the issues and problems which beset it. There could be many reasons for this: lack of access to education, lack of financial stability, etc. Figures suggest that, in 1919, only 8.5% of the Scottish Catholic school population enjoyed some form of post-elementary education, a figure that had risen to only 13.9% in 1939. “Glasgow only possessed five Catholic doctors in 1905,” reports Tom Gallagher in Glasgow: The Uneasy Peace. “Prejudice in the middle-class professions made it easier for those Catholics who secured a full education to start their professional careers elsewhere unless they were servicing the needs of the Catholic community as doctors or lawyers. The university-educated Scots Catholic was more likely to make a name for himself outside Scotland.” The implications this has had upon the community itself is interesting. Few of us can lay our hands upon a book which allows us to glimpse ourselves, which sheds some light upon where we fit into the greater scheme of things in Scotland and Britain. We can’t lay our hands upon such a serious work because as far as I can see none exists. One of my sisters still clutches her copy of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn like a lucky talisman simply because it told her more about our family than any Scots novel ever could.

That simple anecdote about my sister’s favorite book, to me at least, speaks volumes about the predicament of the Irish community in Scotland. We’d show you our feet if we could just find them. I know I’m still trying to find mine. I’m sure my mother and father and all the rest of my forebears left them lying around somewhere.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply