The 50th anniversary of the All-Ireland Football Final, played in New York.

It’s been fifty years since County Cavan pulled a stunning upset victory against County Kerry at the Polo Grounds in New York City, in the only All-Ireland Gaelic Football Championship ever played outside of Ireland.

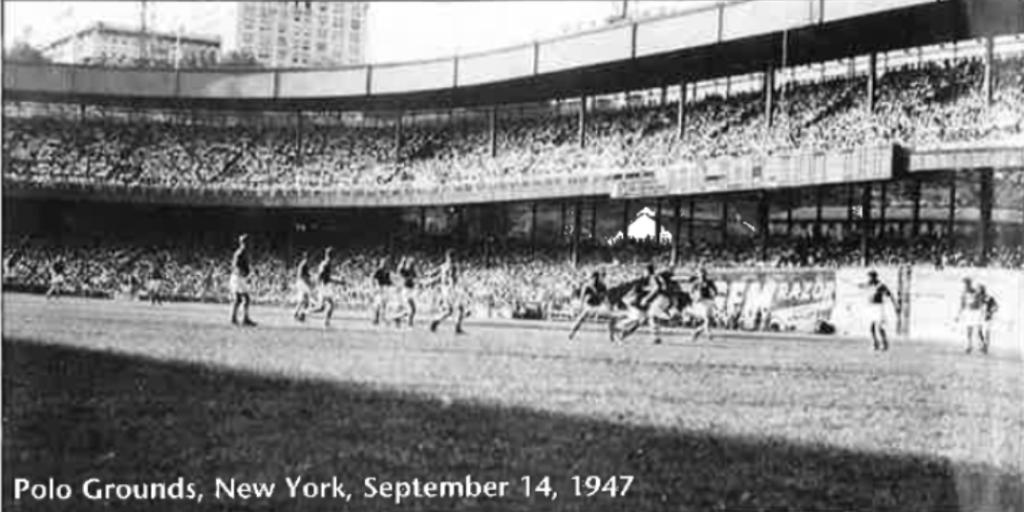

Back on September 14, 1947, the local press in New York seemed not to know what to make of the entire spectacle. The next morning’s Daily News described the 35,000 fans who packed the Polo Grounds as “howling Hibernians” while the on-field battle was described as “fast action, reckless daring and wild courage.”

One of the most colorful descriptions of the day was penned, surprisingly, by Arthur Daley, dean of the city’s sportswriters who drew the assignment for the New York Times. He labeled the hard-hitting game played without pads and helmets as “legalized homicide.” The star of the Cavan team, Peter Donohoe who scored eight points in the historic match, was promptly dubbed by the Times men as the “Babe Ruth of Gaelic football.”

Of course, none of the sports stories grasped the wider drama that was being played out before their eyes: that for the very first time, the Sam Maguire Cup — the top prize in a sport that had been crucial to Ireland’s national pride and identity — was leaving the country. It was meant as a gesture of friendship to Ireland’s exiled children in America.

The year selected for the gesture — 1947 — was no accident. It was 100 years after 1847 — the worst years of the Great Famine which had effectively wiped out, through starvation or emigration, half the eight million people who lived in Ireland in the early 19th century. To this day, Ireland remains the only country in Europe whose population today is half what it was 150 years ago.

As much as the Famine remains a permanent wound in a national psyche, Gaelic football remains a source of burning national and county pride. Another key reason for the game was to help revive the Game of Gaels, which had been hurt by the absence of young men as Irish and Irish Americans marched into World War II resulting in virtually no emigration during the war years to the States and elsewhere. Today, the games of the Gaels are played on every continent in the world except Antarctica.

By game day, September 14, 1947, Kerry had won the Sam Maguire Cup 16 times. They were proud of their football tradition in Kerry, a county so large it is called the Kingdom. “There are only two kingdoms,” the locals say to this day. “The Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Kerry.” The ’47 team had many of the same men who won the cup in ’39, ’40 and ’41 and then came back to win in ’46.

Cavan had always been a low-key province of small farms, little tourism and fierce independent pride. Heading into the ’47 championship, Cavan had carded home the Sam Maguire Cup only twice but was the first team from the historic nine-county Ulster province to do so. It was 12 years since they last held the cup. (Cavan was one of the three counties in Ulster that became part of the 26-county Irish Free State in 1922 while the remaining six Ulster counties formed the new statelet of Northern Ireland).

Even though many of the Kerry team members were nearing the end of their careers and even though Kerry star Paddy Kennedy was forced to line out at left full forward due to an injury, the Kingdom’s men in green and gold were heavy favorites to repeat their winning streak.

Fifty years ago, all across Ireland, after the local games were played and the evening cows milked, thoughts turned to the final in New York. The entire nation gathered around radio sets. As with all things Irish, the match in the Polo Grounds started late. Towards the game’s end, legendary sportscaster Michael O’Hehir, doing the play-by-play back to Ireland, knew the clock was ticking and at five minutes to five realized the game was going to run past its 5 p.m. cut-off time on the AT&T cable.

“I remember listening to Michael O’Hehir pleading with them to keep the wires open,” said Seamus Linnane, then a 13-year-old boy and now a Catholic priest back in Ireland.

In fact, in his autobiography, O’Hehir entitled the chapter on the game, “Give me Five Minutes More….”

Fortunately, O’Hehir got his wish and Ireland got to hear the entire game uninterrupted. Said O’Hehir in his book, “Can you imagine the uproar, the anger in Ireland if we had gone off the air with a few minutes to play?” The Irish Independent said “the biggest radio audience in the history of the GAA and Radio Eirann.”

“The success of the day is that we’re still talking about it fifty years later,” said Linnane at a dinner in Ireland earlier this year.

“It was packed,” said Edmund Stack, a youngster growing up in America who had gone to witness the historic showdown. In reality, about 34,941 showed up in a stadium that sat about 50,000 — but to those who were there for the wild shootout in the sweltering heat, it seemed a sellout. The game was said to have pulled in £38,000 or $153,877.

But it might never have been were it not for a letter “home” that Spring by an emigré lamenting how he missed many things, but most especially missed never being able to see the game of Gaelic Football played the way it was played back in Dublin’s Croke Park at the championship match.

It was a beautiful and moving letter.

And rumor has it that it may have been a total fraud as well. Father Michael Hamilton, a representative of County Clare and strong ally of the New York Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) and its rising advocate, John “Kerry” O’Donnell, lobbied furiously for the championship to move to New York to revitalize the game here. Since backroom arguing is one of the more popular activities associated with the Gaelic Athletic Association, it is guaranteed that the move was not met with universal approval. There were some who felt it would be sacrilege not to play the game before a big crowd in Dublin, where it was a guaranteed sellout. More pragmatically, there was the sheer cost of paying to move and lodge both teams 3,000 miles away. “It was controversial taking it out of Ireland and it took some courage,” recalled Mick Higgins, Cavan’s center forward who was to star in the historic match in New York.

But Hamilton probably knew that the Irish could not resist an appeal to the heart.

Once the letter was read at the Spring Annual Congress of the GAA, the motion was passed. The 1947 championship game that fall was coming to America.

And with a trip to America as the top prize, many fans in Ireland took to bringing the Stars and Stripes as well as their county colors to games that year. In the semifinals of ’47, Cavan beat Roscommon on August 4 before a crowd of 60,075 — setting a new attendance record. A week later, the record was shattered when 65,939 showed up to see Kerry beat Meath.

And so the stage was set.

The starting teams for Kerry and Cavan flew to America on the TWA Skymaster. It would be the equivalent of a sports team today flying the Concorde to a championship. But the four-engine propeller plane was not exactly a non-stop transatlantic flight. The plane was delayed for 12 hours at Shannon and when first airborne, flew south to the Azores, about a third of the way across the Atlantic, to refuel. Then it flew north, touching down in Newfoundland in Canada, and then briefly stopped in Boston to have visas and small pox vaccination papers checked. The players saw blistering heat then snow before touching down in New York 29 hours after leaving Ireland.

“I used to tell people that we had to push the plane to get it started and then we all piled in after,” said Mick Finucane of the Kerry team. They finally landed in New York, which was experiencing a mid-September heat wave, with high humidity and blistering 85 degree heat.

The second team and the referees were sent by steamer, and crossed in the relatively quick time of five days from Cobh, in County Cork to New York Harbor.

One of the passengers on the ship journey was a young Mayo man, Frank Durkan, emigrating to America where his uncle, William O’Dwyer, was the Mayor of New York City.

Of course, while most of Irish America in the city was primed for the visit, the majority of sports fans was more enmeshed with the local pennant races. The Yankees were cruising to the pennant over the Red Sox and the Brooklyn Dodgers, with Jackie Robinson heading to Rookie of the Year honors, were building a seven-game lead enroute to the pennant against crosstown rivals, the hated New York Giants. The Irish championship game made the famous back sports page of the Daily News, but top billing in the next day’s paper still went to the Dodgers and Giants race. The GAA game had to share second billing with Jack Kramer who won the tennis championship at Forest Hills.

It was doubtful if any of the players realized they did not have the undivided attention of the city. Landing in New York, it was red carpet treatment all the way. Francis Cardinal Spellman greeted both teams and offered mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on game day.

Brendan Kelly, a back-up player for Cavan, recalls, “Americans were very good to us. We were invited to the home of Mayor O’Dwyer.”

“The understanding engendered by this memorable occasion will endure to the benefit of the citizens of the American and Irish nations in all the years to come,” said O’Dwyer at the time. For once, a politician’s proclamation rings true fifty years later.

There was a tickertape parade up Broadway on the Saturday evening before the Sunday game. “It looked like we were going through canyons, the buildings were so tall,” recalled Finucane.

“I remember a construction worker stuck his head out and shouted, `How are things in Glocca Morra?'” recalled Cavan’s back-up goalie Brendan Kelly.

Finucane, one of the youngest players on the veteran Kerry team, emerged as something of a celebrity and team spokesman by quipping to the astonished local press that things were “fair and dry” in Ireland. He also recalled in a recent interview the great sport that both teams had in trying to send the reporter from the Dublin-based Irish Press uptown when the teams were heading to events downtown and vice-versa. The Press, to conserve money had sent Anna Kelly, its women’s editor to accompany the team although it was Arthur Quinlan, who was living in New York at the time, who actually drew the assignment for game day.

In a solemn moment, when the two teams packed up to visit West Point, three of the players donned the Irish Army uniforms of their young nation, Lt. Joe Keohane from Kerry, and on the Cavan side Commandant John Joe O’Reilly and Lt. Simon Deignan.

There were fights to watch at Madison Square Garden and even Gene Autry was in town for a rodeo.

The New York Police Department Emerald Society tossed a bash. And the New York GAA tossed a gala semiformal luncheon at the old Roosevelt Hotel in Manhattan on September 10.

“We were feted,” said Cavan man Joe Stafford, then a 29-year-old who would reverse Kerry’s early momentum and begin the Cavan comeback by scoring the first goal for his team on September 14. But there was plenty of life before the game. “Every saloon we went into there was no money accepted — it was all free. We had a wonderful time. It was my first trip to New York and I loved it,” said Stafford.

The GAA sport then and now seems to be from another era. Stafford, a Cavan hero, was a fruit merchant and a bread van driver for Cully’s back home.

Stafford, who turned 79 and is one of the returning veterans said, “I’m looking forward to it, because it will be my last trip.” Other heroes of ’47 slated to return include Eddie Walsh, and Mick Finucane from Kerry and Mick Higgins, Joe Stafford, Brendan Kelly and Peter Donohoe from Cavan.

Sadly, many of the comrades have passed on. At the Kerry vs. Cork league game in Tralee, County Kerry in early March there was a moment of silence for the death of one-time Kerry captain Tom “Gega” O’Connor. He loved America so much that he emigrated and settled in the Rockaways in the New York City borough of Queens. He died suddenly, only eight months short of the planned reunion tour.

Not a sound could be heard after the public address system crackled with the sad news just before the start of the league game played under a grey wet sky. It asked for a moment of silence in memory of one of the mainstays of the great Kerry teams of the 30s and 40s. In New York City, Frank Durkan, now a successful activist attorney in the law firm of O’Dwyer &Bernstein, founded by Paul O’Dwyer (younger brother of William O’Dwyer) did the eulogy for Gega O’Connor.

The survivors of ’47 grow fewer each year, but the men who survive recall the game with crystal clarity, as if it were yesterday.

Throughout most of the first half, the Kerry team appeared to be building a commanding lead and went up eight points to two. As the Daily News noted at the time, “Cavan won the toss, and for a while, it appeared that was all they would win.”

But the tide soon turned. “My greatest memory of the day was scoring the first goal for us,” said Stafford.

Cavan center forward Mick Higgins scored the goal that put Cavan in the lead just as the first half was ending.

“We never looked back after that,” said Stafford, who is as famous today for his hats off the field as he was for his play on it. At half-time, Cavan was up by one point over Kerry’s 2-4 (two goals and four points).

Several key Kerry men went down in the first half. Eddie Walsh, who had been marking the great Cavan wing forward Tony Tighe, was landed an elbow into one of his eyes in one dust-up and the swollen eye forced him out early. Sportscaster O’Hehir had once said that “the fastest hands for the ball I ever saw belonged to Eddie Walsh of Knocknagoshel.” And Walsh, who had already amassed five All-Ireland medals, was out.

More bad luck befell Kerry later in the first half when Eddie Dowling went down after taking a wrenching tumble. Many on both sides saw his fall as decisive. “The turning point was when Eddie Dowling went,” said Walsh, in an interview at Walsh’s Bar in Knocknagoshel, now run by son Eamon.

“He went up for a ball and he came down on his head,” recalled Finucane. The fall was tougher because the pitcher’s mound on the baseball diamond had not been leveled for the GAA match and Dowling landed on it. He left the game woozy with a concussion and was out of action for the day.

Higgins on the Cavan team also felt it was a crucial blow to Kerry’s chances. “Eddie Dowling played for about 20 minutes and while he was playing, they were winning,” he said. “If he had been there, we wouldn’t have gotten them.”

Observers also recall that the heat was taking more of a toll on the Kerry team — where many of the veterans were in their 30s and nearing the end of their playing days — than it was on the younger legs of the up-and-coming Cavan team.

In the opening minute of the second half, Kerry rallied when Gega O’Connor tied the game with a point. But then Kerry’s defense appeared to flounder and Cavan’s star, full forward Donohue, scored four unanswered points to put Cavan ahead for good.

One of the best plays by Cavan’s men in blue was said to have occurred three-quarters of the way through the second half. It was a 70-yard play that involved Cavan’s Phil Brady picking the ball up at mid-field. He brought it down to left forward Tony Tighe who feinted a shot and passed to T.P. O’Reilly, who scored from 14 yards out.

By game’s end, Cavans blue had two goals, 11 points to the Kerry green and gold’s two goals, seven points. Each goal counts for three points, so it meant Cavan had a 17 to 13 victory.

It was one of the more bruising championship games and one for the ages. That evening, 1,400 showed up the Commodore Hotel for the post game dinner. Both teams sailed for home together on the Queen Mary, which one night in their honor printed the ship’s menu in Irish Gaelic. Stafford recalls he was nearly drowned in the ship’s swimming pool by a teammate who did not realize Stafford could not swim and was only pulled to safety by two other mates who alertly realized his difficulty.

They arrived home on the night of October 2nd, and were received by President Sean T. O’Kelly and Taoiseach Eamonn de Valera the next day. They had a parade thrugh Dublin and a banquet later that night at the Gresham Hotel.

Now it’s coming full circle, the GAA in Dublin has made another gesture of support to its exiled children in America as we approach the 50th anniversary of the ’47 game. They are dispatching the current senior teams from Kerry and Cavan to America once again. They will play in a national league game, and be accompanied by the surviving heroes of ’47. Over 2,000 people are expected to fete them at Terrace on the Park at the old World’s Fair site in Queens on October 18, the day following the commemoration Cavan-Kerry game.

As Father Linnane commented at a local GAA dinner in Kerry in early March which was honoring the Kerry and Cavan teams from ’47: “Part of the evening is looking back. But if we don’t take the torch that has been passed on to us and carry it into the future, then we will all be diminished.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September / October 1997 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply