Frank Shouldice explores the relationship between Irish travellers and the settled community.

When Mary Robinson announced she would not be staying on for a second term of office as President of Ireland it was worth observing the reaction from various quarters.

For most people, the announcement heralded a conclusion to a uniquely popular presidency. As a most impressive public figure she brought vitality, intelligence and charm to a previously moribund ceremonial office.

Robinson will be a hard act to follow but without doubt, some minority groups will really miss her.

One such group is Ireland’s traveller community. It’s a social grouping in which Mary Robinson, unlike almost every public representative, has taken close personal interest. When she invited a group of 30 women from the Clondalkin Travellers Development Group to Aras an Uachtaráin (official home of the Irish President) they were the first travellers to be welcomed there.

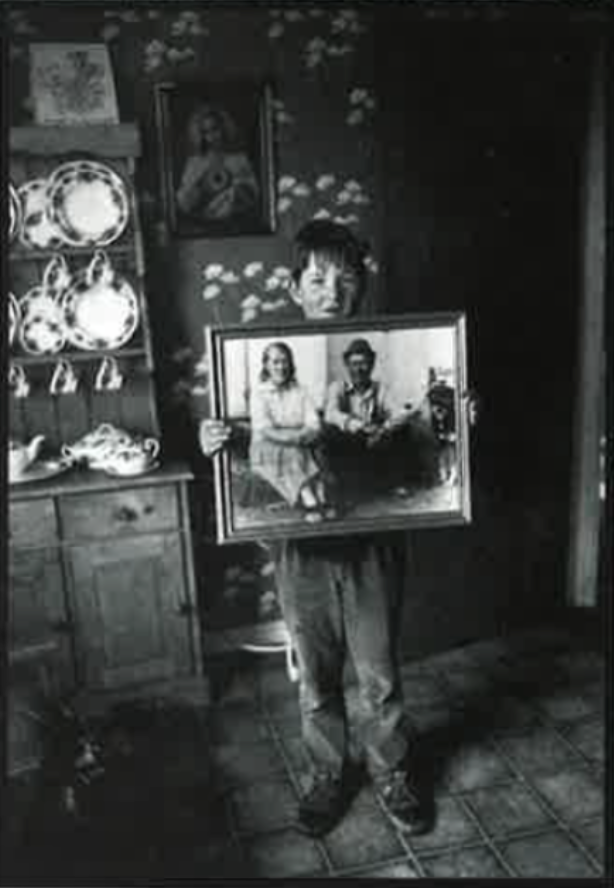

Her involvement with them has been reciprocated with genuine respect and affection. Travellers are fully aware she became their champion, giving them strong representation within the political establishment. For a minority that continually pays for its preference to exist on the fringes of society, the president’s support has been invaluable. Numbering about 30,000 in total, only a small percentage of travellers live in houses. Most live in caravans or mobile homes and move around the country, parking at official and unofficial campsites for weeks or months before moving on. It’s essentially an outdoor life although traditional trades, such as tinsmith or novelty carvings, have become outdated.

Unemployment is extremely high and the vast majority receive welfare assistance. Some have adopted door-to-door businesses, selling carpets, or laying tarmacadam on private driveways. Others deal in scrap metal, usually by recovering abandoned cars and selling car parts.

The situation is not so simple however. Relations between travellers and the settled community are fraught with tension. The nomadic tradition of the travelling lifestyle is scarcely understood by those who pursue a more conventional way of life.

Misunderstanding translates into low tolerance, and violence against travellers is not uncommon. Other forms of prejudice, whether refusal of services at shops and bars, are also widespread.

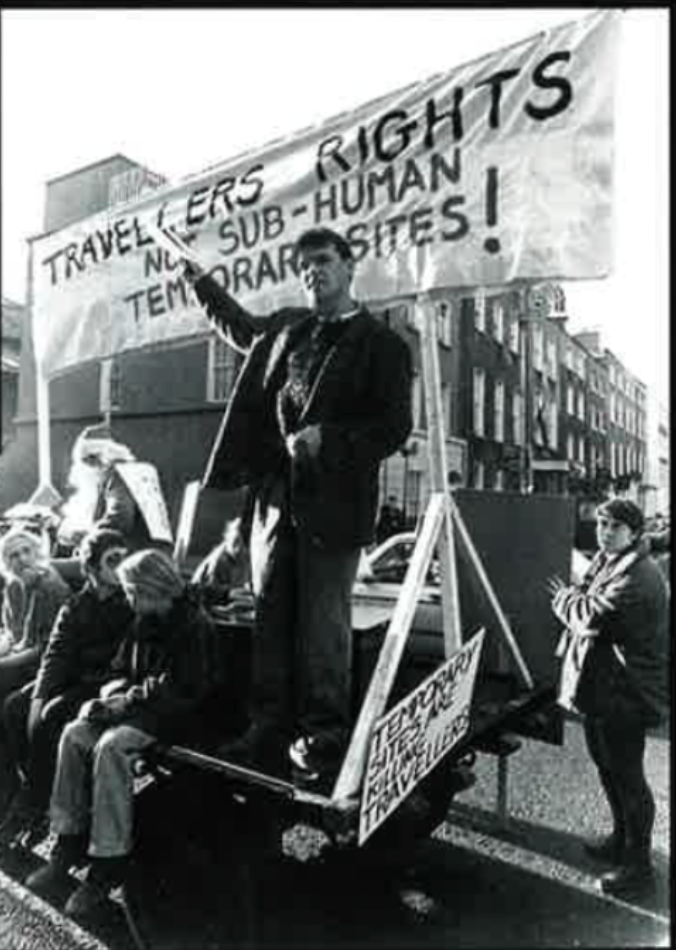

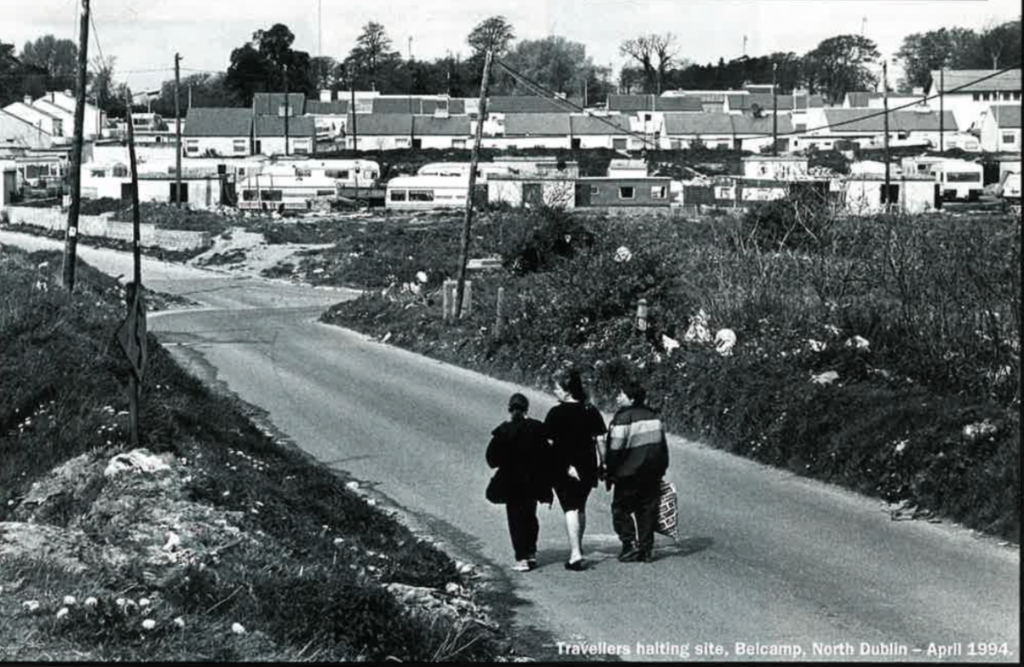

Where travellers are concerned, local authorities in Ireland have also faltered in their legal obligation to provide housing for all constituents. The principle is quite simple: rather than provide standard housing, each authority is supposed to provide a number of secure halting sites for travellers. Ideally, these sites work like fully-serviced caravan parks but the main difficulty is that settled communities invariably object to having sites located anywhere near them.

With some exceptions, the outcome is that official sites are placed in the most inhospitably remote areas where nobody would want to live. Services are completely inadequate. In Mulhuddart, Co. Dublin, for example, over 32 people shared one cold water tap up to last year while in a nearby Dunsink site, 38 people shared one toilet.

At the Dunsink site, located right beside a refuse tip, there was no electricity. The nearest shop lay two miles away at the end of a narrow, winding road and garbage was collected, not once a week like settled people reasonably expect, but once every two months. The appearance of both sites reflected this thinking.

The broader impact is that travellers feel they cannot get what is due to them so they set up unofficial sites wherever possible. Without any services at all sanitation is almost non-existent. The accumulation of scrap — abandoned cars, refrigerators, metal — makes roadside sites a chaotic and unsightly mess.

In this way society’s prejudices are quickly reactivated. Settled people see the run-down state of unofficial sites, which are notoriously dirty and unhygienic, so when the next application for an official site is made, the objection is almost routine.

Whatever the many foibles of the settled community, it seems finding ways to describe travellers comes easiest with descriptions like dirty, lazy, greedy, untrustworthy, irresponsible and/or alcoholic. But just as many travellers are not like this at all, these adjectives could equally apply to a minority within the settled community.

A discussion of this unhappy relationship prompted Jim MacLoughlin of University College Cork to conclude his “Travellers in Ireland” study by saying, “Keeping travellers on the move has become a national obsession in Ireland.”

He continues, “This form of `ethnic cleansing’ should be as unacceptable here as it is elsewhere in Europe.”

Indeed the ritual application and rejection of council sites for travellers has marked the entire country. Despite a Sunday Independent/IMS survey last year which found 61 percent of respondents in favor of accommodating the lifestyle of travellers, it seems each time a site is selected the plan is scuppered by local objection.

Public compassion is deeply ambiguous. Even if the majority appear sympathetic to cultural difference, sympathy evaporates on personal doorsteps. Find a place for “them” – as long as it’s not here.

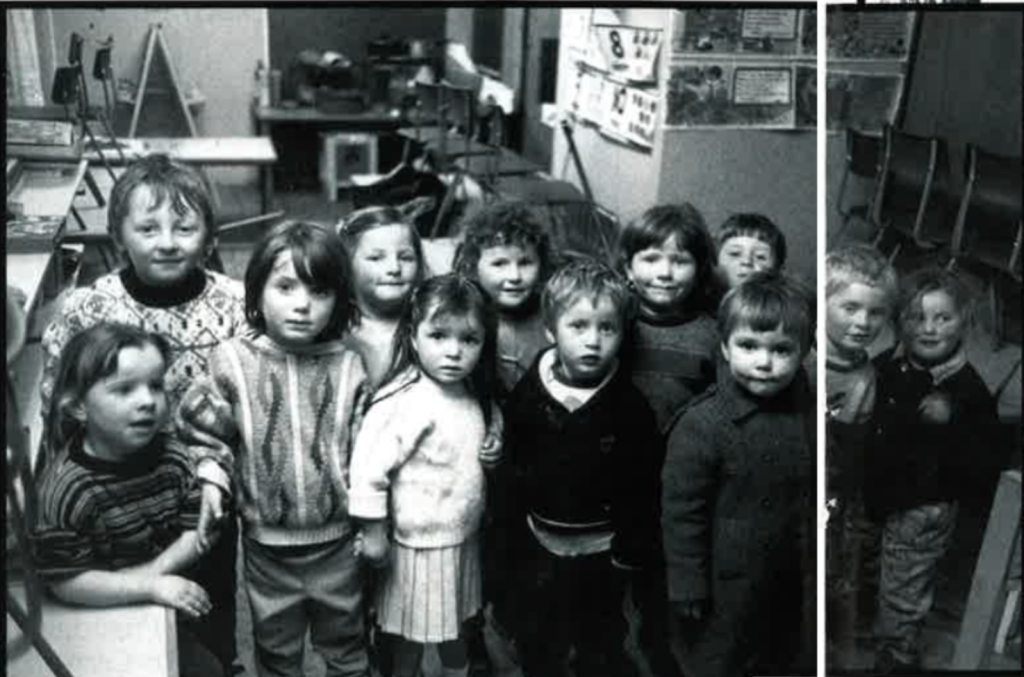

The origin of Irish travellers — known variously as gypsies, tinkers, itinerants or more derisively as knackers — is less clear. Raised with the most basic education — if any — literacy levels have alway been very low among travellers. Their tradition is oral, not written, so research into the history of travellers is hampered by the complete absence of records.

The debate into the origin of European gypsies, for example, has led inconclusively to beginnings in Romany, Egypt and India. Historical connections between Irish travellers and the world’s nomadic community have yet to be determined. There is also the notion that at least some of the travellers are descendants of those driven from their lands during the Cromwellian “To Hell or to Connacht” reign of terror, or from the 200,000 evictions that took place during the Famine era.

Comparisons between European gypsies and Irish travellers are quite obvious — early marriage, high birth rates, high infant mortality rates, lower life expectancy, strong religious beliefs, closer connectedness between families (frequently with cousins marrying) and isolation from the rest of society.

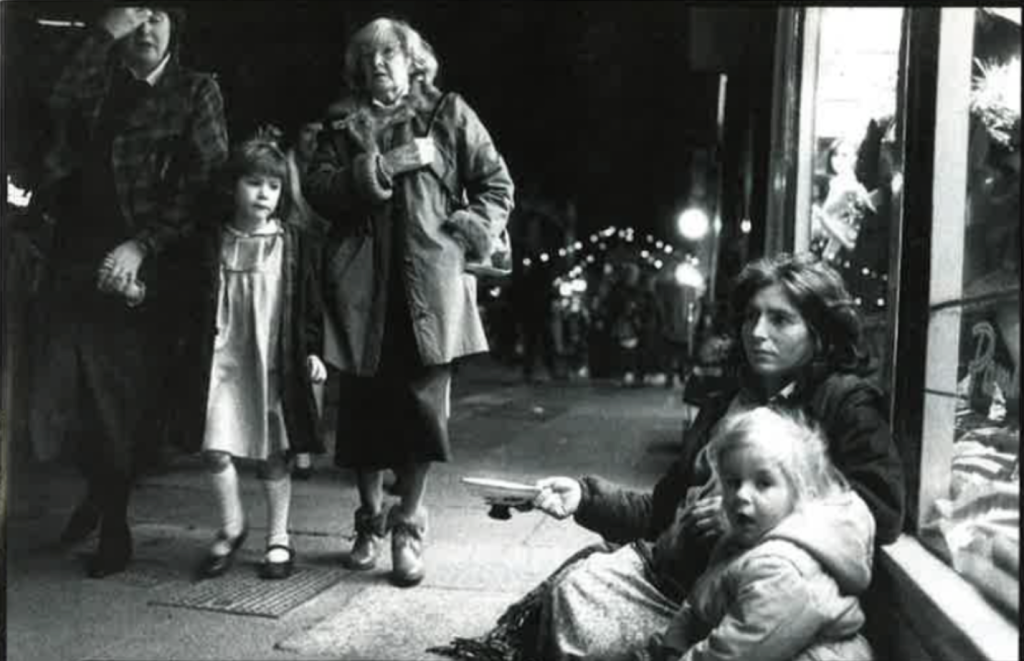

The most visible form of traveller life in major Irish cities is street begging by children. To most people this is an appalling indictment of how travellers treat their children. The fact is however, that most traveller families would never subject their children to this type of abuse.

“Only a very small amount of travellers beg,” counters Nancy Collins of Pavee Point, a Dublin-based traveller organization. She points out how the entire minority community always take a rap for the actions of a small number.

“There’s a few people that beg but why blacklist everybody for it?” asks Collins. “A lot of travellers I know wouldn’t dare put their children out to beg. Within the travellers it would be looked clown on, that they shouldn’t be doing that with children. But no one can interfere with that. That’s their family.”

“I think with rights there come duties and responsibilities,” says Martin Collins (no relation) also of Payee Point. “We acknowledge that some travellers need to be challenged about that. There are some that don’t do their rubbish properly — just as there are in the settled community. But it’s very difficult for travellers to fulfill their responsibilities when they have not been given their rights in the first place.”

Jim MacLoughlin’s study stands as a scathing indictment of national policy on travellers. He makes a strong case that their adherence to a nomadic lifestyle itself almost now passes as a criminal offense, as though by being different to the majority they relinquish ordinary rights as Irish citizens.

In the Greater Dublin area for example, over half of the travelling community have no access to hot water, electricity, bath or shower facilities. Not one halting site provides access to a public phone. Little wonder that MacLoughlin writes, “This type of anti-traveller racism is rooted in a belief that the way of life of settled people is the modern norm and that the way of life of travellers is a throw-back to less civilized times that are best forgotten in a modern society like Ireland.”

The negative image is easily reinforced. Many travellers realize that as soon as one traveller commits a crime or is seen drunk the entire travelling community takes the blame. Minorities, they have discovered, provide ready scapegoats for the majority.

Some recent developments include halting sites designed and managed in consultation with travellers. Up to now they have been excluded from policy-making. The indications are that a project like the £2 million St. Oliver’s Park halting site near Clondalkin is the way to go.

There are no abandoned cars lying around. No dirt, no litter. A large refuse dumpster sits in the comer like a communal bin, collected each week by the Corporation. The estate’s general cleanliness suggests local pride among its residents. Their own sentiments confirm this, reflecting a positive change of heart and a housing model that works.

“Travellers’ achievements are never celebrated,” argues Martin Collins. “The only media coverage is around the accommodation issue, usually in a conflict situation. Or two travellers down the country having a bare fistfight. You never see any other aspect of our lives in the media.”

One of Pavee Point’s objectives is to promote a better understanding of traveller culture. If tolerance is the first obstacle to understanding, the settled community is certainly proving slow to respond.

But is the settled community always to blame? No traveller will claim to belong to a community of angels. In this they feel they have at least one thing in common with the rest of society.

Leave a Reply