CO-FOUNDER OF AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL – 1961

UNITED NATIONS COMMISSIONER FOR NAMIBIA – 1973

AWARDED THE NOBEL PEACE PRIZE – 1974

THE LEVIN PEACE PRIZE – 1977

THE AMERICAN MEDAL FOR JUSTICE – 1978

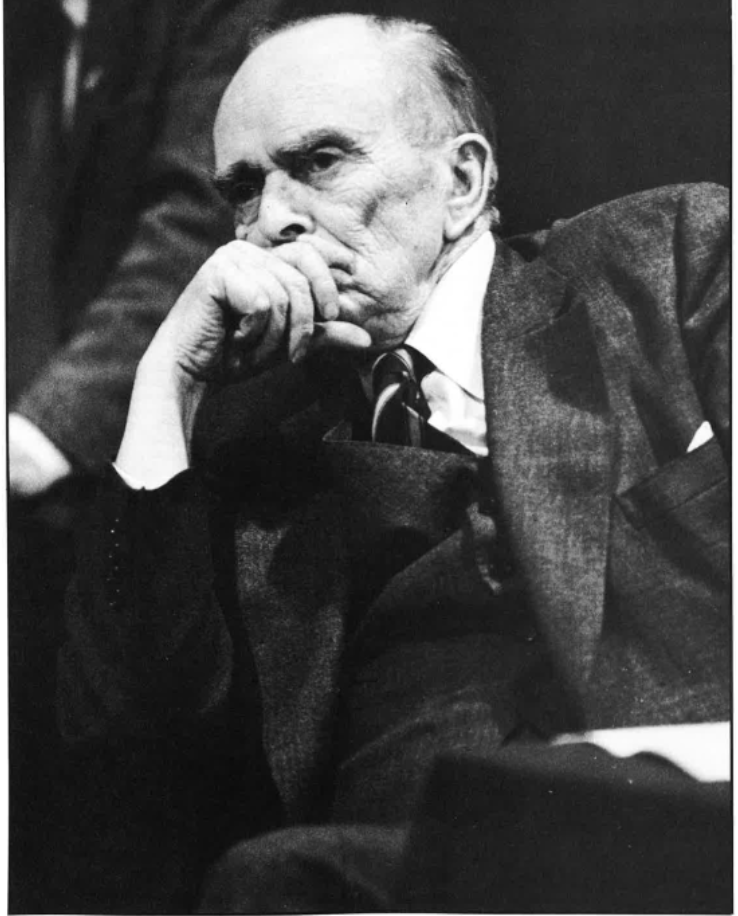

Seán MacBride’s career spans the history of independent Ireland.

His father was executed by the British after the 1916 Rising, when Irish independence was first proclaimed. As a teenager, he fought in the War of Independence and went with Michael Collins to the London negotiations in 1921 that produced the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the New Irish Free State.

He took the Republican side in the Irish Civil War and was with the anti-Treaty IRA leaders the night before they were executed by the Free State authorities in December 1922. He was Chief of Staff of the IRA in the 1930s and was Foreign Minister in the government that declared southern Ireland a Republic, taking it out of the British Commonwealth in 1949.

MacBride went on to become an international statesman. He was a joint founder of Amnesty International in 1961, United Nations Commissioner for Namibia in 1973, and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1974, the Lenin Peace Prize in 1977, and the American Medal for Justice in 1978.

Seán MacBride was born in Paris in January 1904. His parents were two of the best-known Irish rebels of the time – Major John MacBride, who had led an Irish Brigade fighting against the British in the Boer War in South Africa, and Maud Gonne, a famous beauty who had been deeply involved in the Irish land struggle in the 1890s. The poet W. B. Yeats was in love with her and wrote some of his most famous poems about her.

The young MacBride grew up in a house filled with poets and revolutionaries and was to become an active IRA member and organizer for almost 20 years. He then became one of Ireland’s most distinguished political and criminal lawyers and founded a new political party that ended 16 years of unbroken rule by Eamon de Valera and his Fianna Fail party.

As well known abroad as at home as a tireless campaigner for human rights and peace, Seán MacBride is still extremely active, advocating disarmament, opposing apartheid, and campaigning against injustice in Northern Ireland. He is a frequent visitor to the United States, where he has recently sponsored the MacBride Principles in an attempt to end discrimination against the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland and has opposed the new Extradition Treaty with Britain.

Dr. MacBride’s wife, Catalina “Kid” Bulfin, a former member of Cumann na mBan, the women’s section of the IRA, died in 1976. He has two children, Tiernan and Anna, who both live in Dublin.

Irish America: We are approaching the seventieth anniversary of the 1916 Rising. Your father was executed for his part in the Rising. What are your memories of that?

Seán MacBride: I was at school in France at the time when I heard of my father’s execution. I appreciated very much the way the French reacted. At the school, every week, there was a ceremony for any of the boys’ fathers who had been killed fighting in World War I, and they included my father, who had died fighting not for the Allies but against them for the freedom of another small nation.

Irish America: On your return to Ireland in 1917, wasn’t your mother also arrested?

MacBride: Yes. In 1918, the British announced they had discovered a German plot, and pretty well, all the Republican leaders were rounded up and interned in England. I commuted between Dublin and London to see my mother, who was in Holloway jail, and W.B. Yeats gave me his flat in London to stay in.

Irish America: Of course, Yeats is now recognized as one of the most important poets of the twentieth century. What was your impression of him?

MacBride: He and James Stephens [another famous Irish writer] were very frequent visitors to our house. I liked him and got on well with him. He taught me how to fly a kite. But I preferred James Stephens. I thought Yeats was a bit distant from me as a child, whereas James Stephens was full of stories and fun. Mother was very fond of Yeats, but she was always worried that he might succumb too readily to British influence. I remember heated arguments at home about the possibility that he might be made Poet Laureate or offered a British title. Mother said, “If you accept a British title, you need never come into our house again.”

Irish America: You became involved in the IRA yourself about the beginning of 1919 when you were 15, isn’t that right?

MacBride: I was involved in the Fianna [IRA youth wing] at first, and that was accepted at home, but mother didn’t want me to join the IRA. She thought I was too young. I transferred to the IRA without her knowing about it.

I joined an IRA company that wasn’t in the area where we lived – B company of the Third Battalion, Dublin Brigade, that was operating in Pearse Street, Mount Street, Baggot Street area. I formed an active service unit, which was very active because we had in our area the main route between Beggars Bush barracks, the headquarters of the Black and Tans, and the city. You could mount an ambush at any time of the day and be pretty sure you would not have to wait too long for some convoy to pass by.

In 1920, Michael Collins sent for me and asked me to investigate the possibility of an arms deal that had been suggested by Clan na Gael in America – to raid a dump of British arms on the French coast. I did and reported back. [It did not come off.] Later, in 1921, he asked me to form a small Flying Column with some of my men in Dublin and try to get things going in counties Wicklow, Wexford, and Carlow, which had been very quiet.

I was doing this work in Wicklow when I heard of the [Anglo-Irish] Truce. I was very opposed to the Truce because we had been doing very well, carrying out operations that were forcing the RIC [paramilitary police] barracks to close down.

I went up to Dublin and saw Collins and told him I wanted to resign. He argued with me and said, “No. We needed the Truce badly; we had to get more supplies of arms and had to have better training for IRA officers. We needed six or eight months to do this.” He said, “I want you to act as adjutant at an officers’ training camp at Glenasmole, County Dublin,” which I did for a couple of months.

Irish America: Collins took you to London with him as an aide and courier during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations in 1921. What did you think of him, and why do you think he accepted the Treaty?

MacBride: I had a tremendous admiration for Collins. He was my hero, if you like, but I was afraid in London that he was getting swept off his feet a bit by the atmosphere there. I remember him coming back one day from a conference with Lloyd George [the British Prime Minister] and telling us how Lloyd George had put his arm round his waist and had taken him over to a map on the wall where the British Empire was all marked out in red. He said to him, “Mike, we need your help to run this part of the world.” While he used to tell us these things to show he wasn’t taken in by them, I felt they were having some effect on him.

I’m certain he was not satisfied with the Treaty, but he did accept it as a stepping stone. Throughout all that period I had been investigating for him a proposal for the purchase of a very substantial quantity of arms from Germany. He was doing all he could to import more arms and train more officers for the IRA.

Irish America: But he did accept the Treaty, and you were on opposite sides in the Civil War.

MacBride: When the Treaty was signed, I saw Collins immediately, and he said, “I take it you don’t agree with the Treaty, and I can understand why. But we needed more time.

“You just carry on with the projects you are doing on the importation of arms as if nothing had happened, and I will provide any finances you need.” And so I continued on right up to the start of the Civil War, with Collins’ full knowledge and approval.

At the same time he made arrangements with us (the anti-Treaty IRA) for the exchange of arms the British gave the Free State army for ours, which couldn’t be traced, to be sent to the North. This went on until the very eve of the attack on the Four Courts [which started the Civil War].

Rory O’Connor [one of the IRA leaders with whom Seán MacBride shared a cell after they were captured by the Free State forces after the attack on the Four Courts] was convinced that Collins would break away from the rest of them [the Free State leaders], that it was only a question of time, and that an arrangement could be made between Collins and the IRA.

That is a corner of history that needs researching. Collins resigned from the Provisional Government just a short time before he was killed and set up an army council of three people [General Richard] Mulcahy, [General Eoin] O’Duffy and himself. I have an idea that this was linked with reaching a settlement with the IRA and breaking away from the rest of the Provisional Government.

[Collins was killed during an IRA ambush in August 1922, and Rory O’Connor was executed with other Republican leaders by the Free State authorities in December 1922. The Civil War ended in defeat for the IRA in 1923.]

Irish America: You remained actively involved in the IRA throughout the 1920s and most of the 1930s, becoming Chief of Staff for a time in 1936-1937. Then you resigned. Why?

MacBride: I felt that if the Oath [of allegiance to the British king] was removed, and if there was a constitution that recognized the jurisdiction of the state over the whole country, then we should be able to work within the framework of the constitution to achieve reunification.

When the new constitution was adopted [1937], I felt there was no more need for the IRA, and we should put all the energy we had into starting a Republican party. And, by political means, we would be able to achieve reunification and an Irish Republic.

Irish America: Then the Second World War intervened, during which you supported De Valera’s policy of neutrality, and you were kept busy because you qualified as a lawyer and represented many IRA prisoners, including some who were sentenced to death and executed. But eventually, in 1946, you started a new Republican party called Clann na Poblachta. What were your objectives?

MacBride: My primary concern was the failure of the government to pursue any forward-looking economic policy, the lack of progress on afforestation, and any long-term development plan. I had several long talks with de Valera on that and I had failed completely to convince him.

Then there was TB [tuberculosis] and hospital building and monetary policy, the policy of the government of investing all its money in England.

And there was the question of the treatment of prisoners. There had been the McCaughey inquest [on an IRA prisoner who had died on hunger strike in protest at conditions in Portlaoise prison].

And, of course, Partition was very important, as the repeal of the External Relations Act [which kept the State linked with Britain].

Irish America: Your intervention in the 1948 election ousted De Valera from power after 16 years and you became Foreign Minister in Ireland’s first coalition government. How do you assess that government now?

MacBride: It was a very good government in many ways, probably about the best one we have had. It accepted the policy of investing more in Ireland and utilizing the Irish Hospitals Trust money for building hospitals and eradicating T.B. It released all political prisoners and suspended the operation of the military courts. It was quite active on Partition and it adopted the policy I put forward of planting 25,000 acres of forest lands every year. And the External Relations Act went.

Irish America: You also, of course, declared a Republic and took the state out of the British Commonwealth. But one of the most controversial aspects of that government, which eventually helped to bring it down, was the Mother and Child Scheme – a plan for a free, no-means test health service for mothers and children which was attacked by the Catholic hierarchy, who were opposed to the idea of free medicine for all as constituting excessive state interference. The government dropped the scheme, and Dr. Noel Browne, the young Minister for Health and MacBride’s Clann na Poblachta colleague in the Cabinet, resigned from the government and the party. How do you look back on that and on the Catholic hierarchy’s role now?

MacBride: The issue wasn’t the Mother and Child Scheme. Dr. Browne made it into that. The issue was internal dissension within the Clann itself. Browne was determined to change the leadership of the Clann and bring down the government. The Mother and Child Scheme was only incidental because we had already reached an agreement whereby anybody not in receipt of £1,000 per year would get free medical services…I thought the hierarchy was completely wrong. There was nothing in the health scheme that could be regarded as contrary to Catholic principles. But I felt we couldn’t ignore the hierarchy completely.

Irish America: As Foreign Minister, you took some initiatives on Partition and visited America in that connection.

MacBride: Yes, both before and after the 1948 election, I was in close touch with Congressman John Fogarty of Rhode Island, who had gotten a lot of support for a resolution in Congress calling for Irish reunification.

I spoke quite a lot in the United States and addressed the House of Representatives in support of the resolution. We also built up quite a large organization in England and all our diplomatic missions were used to put the case for reunification. We financed some pamphlets as well; Conor Cruise O’Brien edited them.

Irish America: In 1961, you were one of the co-founders of Amnesty International. How did you become involved in it?

MacBride: Well, I had been very involved in European affairs and had helped draw the European Convention on Human Rights, and I was very conscious that there were many political prisoners still in Europe at that time. Then, an English lawyer named Peter Benenson wrote an article in The Observer about the forgotten prisoners, and a number of other lawyers contacted me, and we met in Luxembourg and set it up.

It made a tremendous impact in Europe at first, and then it spread all over the world.

We secured the release of thousands of political prisoners. I was involved in getting Archbishop Beran of Czechoslovakia released and Agostinho Neto, the future president of Angola. At first, it was relatively easy. It’s harder now and the worst area today is probably Latin America, especially Central America.

Irish America: You’ve been awarded the Nobel and Lenin Peace Prizes and you were the first non-U.S. citizen to be awarded the American Medal for Justice. What were these honors awarded for?

MacBride: I don’t really know. With the Nobel Prize, the award talked about what I had done for human rights in the world. The Lenin Award talked about my work in bringing about better relations between states and working in favor of peace. The American Medal for Justice was for strengthening the rule of law throughout the world.

Irish America: Recently, you have given your name to the MacBride Principles to outlaw discrimination against the Catholics in Northern Ireland, and you have opposed the planned changes in the Extradition Treaty between the United States and Britain to allow the handing over of political offenders. Why have you become involved in these issues?

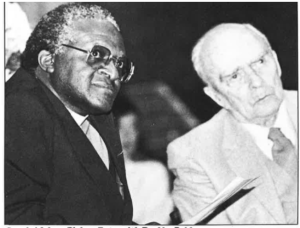

MacBride: Well, on the employment issue, I, first of all, came into direct contact with the Rev. Leon Sullivan, a black clergyman who drafted the Sullivan Principles in regard to employment by American corporations in South Africa to get rid of apartheid, and naturally I thought we should try to apply the same principles in regard to American money invested in Northern Ireland ..I see the issue of discrimination in Northern Ireland as very closely linked with Partition.

The extradition treaty, I think, is a complete reversal of the laws as they have existed up to now. Asylum is a very old right that has been part of international law throughout the centuries, as extradition is merely a branch of the right of asylum…It would certainly be a weakening of the traditional application of international law.

Irish America: You have spent a lifetime in politics and public affairs in Ireland and internationally. What do you see as the most important issues facing Ireland and the world today?

MacBride: The most important world issue is to avoid a third world war because a third world war would inevitably become a nuclear war, and that would probably be the end, not so much of our civilization, but probably the end of the human race.

As far as Ireland is concerned, I think the most important issue is that of the reunification of Ireland and enabling Ireland to develop normally as a national unit and adopt much more advanced and progressive economic policies. The massive unemployment that exists here now is at least in part due to a deficiency in economic planning about afforestation, natural resources and agriculture. All these things have been completely neglected.

Thank you very much, Dr. MacBride.

Note: This interview was published in April 1986. Seán MacBride died in Dublin on January 15, 1988, eleven days before his 84th birthday. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery alongside his mother and his wife, who died in 1976.

Publisher Niall O’Dowd wrote about the MacBride Principles in Irish America’s premiere issue in 1985.

Leave a Reply