The relationship between John Devoy, the legendary Fenian, and Eamon de Valera is explored by Terry Golway.

In Neil Jordan’s film Michael Collins, there’s an 18-month gap in the pivotal conflict between Eamon de Valera and the movie’s hero. We see Collins helping to hustle de Valera out of Ireland, bound for the United States. A few minutes later, de Valera returns to Ireland, scowling when he hears Collins referred to as the Big Fella.

For understandable reasons, most of them having to do with the mind-numbing details that few viewers would appreciate, Jordan chose not to deal with what happened in America during de Valera’s long exile in the country of his birth. Had he done so, the bruised memory of Eamon de Valera might have taken yet another pounding.

Essentially, Eamon de Valera went to America and started the Irish Civil War. So, in an unenviable historical development, Ireland’s civil war preceded its war of independence. By the time de Valera left America, the formidable Irish-American national movement was split in two, in both its public and its secret manifestations. An internecine battle was fought over large issues, such as the proper use of the money being raised in America, to the small, such as the wording of resolutions submitted to American politicians. All of this took place even as the IRA was battling the Black and Tans.

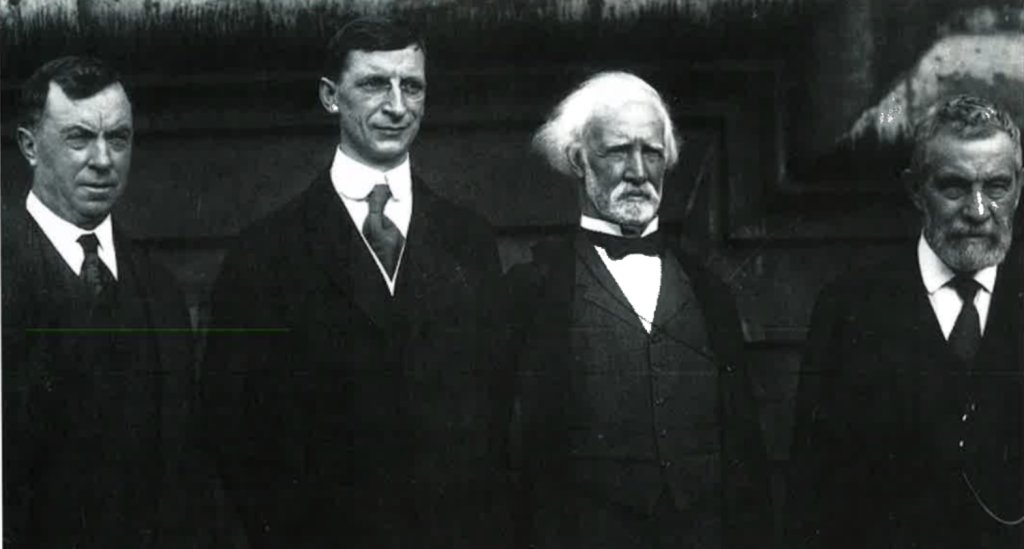

Eamon de Valera’s chief antagonist in America was a short, stout journalist with a quick mind and a talent for pointed invective. His name was John Devoy, a legendary Fenian who had outlived nearly all his contemporaries, and who, in this critical juncture in Irish history, remained a vital part of the trans-Atlantic effort to rid Ireland of British rule.

Devoy was 40 years older than Dev, and he had been the face of Irish-American nationalism for decades. Devoy was just shy of his 80th birthday when he and de Valera met in New York. De Valera established his headquarters in the palatial Waldorf. Devoy, too, lived in a hotel room, but in more austere surroundings. His two-bed room in the Vanderbilt Hotel, near Grand Central Terminal, was about what could be expected for a man who paid himself a salary of $25 a week. Devoy had spent his life in spartan, sometimes close to impoverished, pursuit of a single goal: Irish freedom, to be accomplished through the powerful use of Ireland’s exiles in America.

He came to America in 1871 after winning early release from the British penal system, to which he was dispatched after his arrest a year before the Fenian Rising of 1867. Slowly and with great patience, Devoy rebuilt Irish-American nationalism into a formidable, if stealthy and faction-ridden, force. It was a job that required immense fortitude — every advance, it seemed, soon was followed by retreat or even collapse. Devoy, however, persisted. Several times over, he built the Clan na Gael into Irish-America’s equivalent of the IRA, indeed, they were fraternal organizations and shared a Revolutionary Directory designed to coordinate trans-Atlantic conspiracies. And when he was not organizing, he was preaching — a fine journalist, he edited a paper called The Irish Nation during the Land War and, beginning in 1903, he was editor of the Gaelic American. Both weeklies, they were designed to forward the agenda of Clan na Gael.

To John Devoy, the Clan na Gael had proprietary authority over the Irish-American movement. To friend and foe alike, it often seemed that John Devoy had designated himself as Irish-America’s ultimate arbiter. But after devoting so many years and so many hardships to the cause, Devoy had reason to consider his claim to be legitimate. Eamon de Valera had a different view of things. As the duly elected Priomh Aire (or First Minister) of the underground Dail Eireann, de Valera considered himself the mega-authority to which disparate Irish nationalists and republicans owned allegiance and obedience. Perhaps to drive home the point, in America he would be introduced as President of the Irish Republic — the Republic to which John Devoy pledged his loyalty when he was an eager 19-year-old Fenian.

To say that the Irish Civil War started with Devoy and Dev in America sounds like an exaggeration, and to some extent, it is, at least to the extent that nobody took up arms during de Valera’s stormy American journey. But many of the elements that eventually would pit the Free State against the IRA were very much in evidence when de Valera crossed swords with the foremost Irish-American agitator of his day. By the time de Valera returned to Ireland, the nationalist movement to which Devoy had devoted his life was split, and disastrously so. Anyone who saw what happened in America in de Valera’s wake should not have been surprised when Dev walked out of the Dail after the Treaty vote. (Nor should they have been surprised to see Dev walk back into the Dail in 1926.)

De Valera arrived in New York on June 11, 1919, and promptly was introduced to Devoy and Devoy’s friend and advisor, Daniel Cohalan, a Justice in New York’s state Supreme Court. Cohalan was a formidable figure with an outstanding legal mind. He, too, had suffered for his involvement in Irish nationalism. When America entered World War I, Cohalan found himself fending off charges, fueled by an unfriendly Wilson Administration, that he was a disloyal American. The Wilson White House, remembering Cohalan’s active opposition to Wilson’s nomination in 1912 and his re-election in 1916, released documents showing that Cohalan, along with Devoy, a Philadelphia liquor importer named Joseph McGarrity and other Irish-Americans had been dealing with German agents at the time of the Easter Rebellion. In fact, they had, but they ceased all such activity once America entered the war against Germany. Still, the smear almost worked, and there had been calls for Cohalan’s impeachment.

Like Devoy, Cohalan was prepared to support Dev, and, in fact, the two leaders assisted de Valera — grudgingly at times — with a bond drive that brought in millions of dollars. It wasn’t long, though, before de Valera and Cohalan-Devoy clashed over all manner of issues: the bond drive, de Valera’s infamous suggestion that a free Ireland’s relationship with Britain could be modeled on Cuba’s relationship to the United States at the time, and, especially, de Valera’s high-handed involvement in American politics, about which he knew little.

Devoy began battering de Valera in the Gaelic American week after week. At one point, Devoy played the Collins card in an ill-advised attempt to undercut de Valera’s image. At a time when the British were desperate to find Collins, Devoy ran his picture on the front page of the Gaelic American, under the headline: “Ireland’s Fighting Chief.” A story carried a headline reading: “Michael Collins Speaks for Ireland.” Not long after, de Valera decided that since he could not control Devoy and Cohalan, he would form his own organization. His opponents had their Friends of Irish Freedom organization; de Valera would have the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic. De Valera’s allies in America then split the Clan na Gael into pro-Dev and anti-Dev wings.

De Valera returned to Ireland in late 1920, leaving behind bitterness and division. There would be more bitterness and division to come, and Ireland was soon awash with Irish blood. And when John Devoy returned to Ireland as a guest of the Free State in 1924, he told a Dublin audience that he wished he had been shot with Padraig Pearse and James Connolly in 1916.

He had lived long enough to witness the ultimate Irish split, and the cheers of the Free State did nothing to heal the old Fenian’s wounds.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 1997 of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply