A descendant of Famine immigrants recounts her trip home.

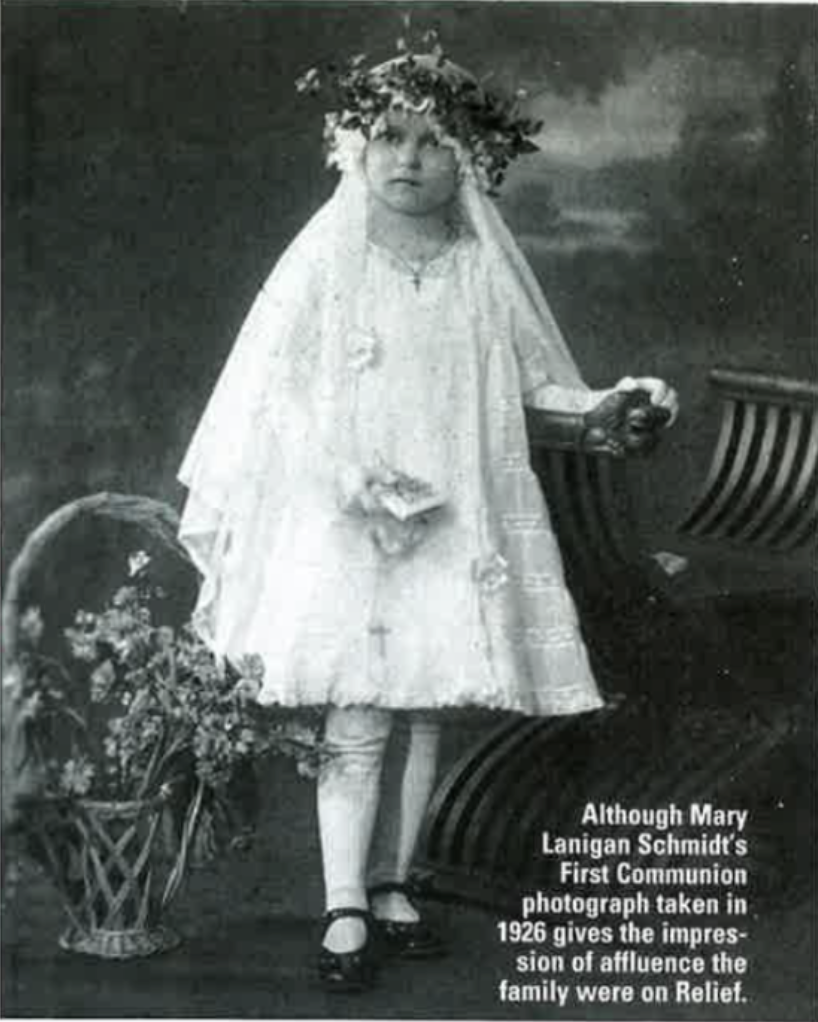

It was our first trip to Ireland. And it was a trip my mother, Mary Lanigan Schmidt, always yearned to make, but never did. Now dead these 12 years, she left behind so much, including her First Communion veil from 1926, now yellow with age. I took two snippets of the delicate lace and brought them with me, a part of her, back to the Ireland she never visited, but always kept close to her heart.

My mother, whose family came over during the Famine years, said her family hailed from Cork. But a Cork cabdriver told my husband and me with great certainty that “the Lanigans and Flanagans were from Tipperary and Kilkenny.” Could it be that because so many of the “coffin ships” departed from Cork, it was passed down in my family that that was where we came from?

Because we had no time to journey to Tipperary and Kilkenny, I buried the first snippet of my mother’s First Communion veil in the dark soil at the base of a tree in the grounds of our Cork Bed &Breakfast, a former monastery. My mother was a deeply religious woman who would have appreciated that part of her veil was being interred in what was once holy ground. My fingers dug into the moist, cool soil and I felt in touch with my roots.

From Cork, after a day of heavy driving, it was time to stop at the town of Listowel. A bustling market-town of 4,000, Listowel is located on the north bank of the River Feale. According to tradition, the river is named for a beautiful princess, Fial, who drowned while bathing in the river now famous for its salmon angling.

Horse racing, music and literary tradition are the big draws of present-day Listowel, home of Maurice Walsh, author of The Quiet Man, and John B. Keane, who wrote The Field and owns the bar bearing his name in the town center. The local tradition of literary achievement and music enables Listowel to claim that it is the cultural capital of Kerry. Many international and top Irish groups are proud to say they have “played Listowel.” But it was the famine graveyard that left an indelible impression on us.

“Teampaillin Ban,” or little white churchyard, located a quarter mile outside Listowel on the Ballybunion Road, is “where many nameless victims of the Irish Famine 1845-47 were interred in mass graves,” as the signpost at the entrance notes. Next to the sign, a narrow path that passes a makeshift iron crucifix fashioned into the wall, leads onto a stone walkway that borders a field; the graveyard itself is surrounded by a bit of a fence.

A large Celtic cross inscribed: “Erected 1932. In Loving Memory of GOD’s poor. R.I.P., P. Whelan, Listowel” marks the grave. There are no headstones. A wooden frame shed serves as a shrine to those departed. Empty plastic bottles of holy water lie about a small table where a large holy picture is adorned by old plastic flowers that spill out of a vase. Ironically, a handcarved depiction of the Last Supper sits on top of one of the limestone columns that border the cemetery.

An eerie quiet pervades as we walk the stone path and survey the graveyard. Were any of my relatives — the Lanigans and Flanagans — interred beneath the grassy expanse, below our feet? I will never know.

I felt an urgent need to return to Cork. My husband agreed. At Cobh Harbor, I took the remaining piece of yellowing lace from my mother’s First Communion veil, and let it fall into the green waters. And I said a prayer for all my relatives who perished in the Great Hunger, and for those who survived. But for their efforts, I would not have been able to “come home” to the land that my mother had always wished to see.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 1997 of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply