Daylight hasn’t quite settled over north Co. Wicklow yet, but even at 8.30 a.m., this Monday is already teetering on the brink of total disaster.

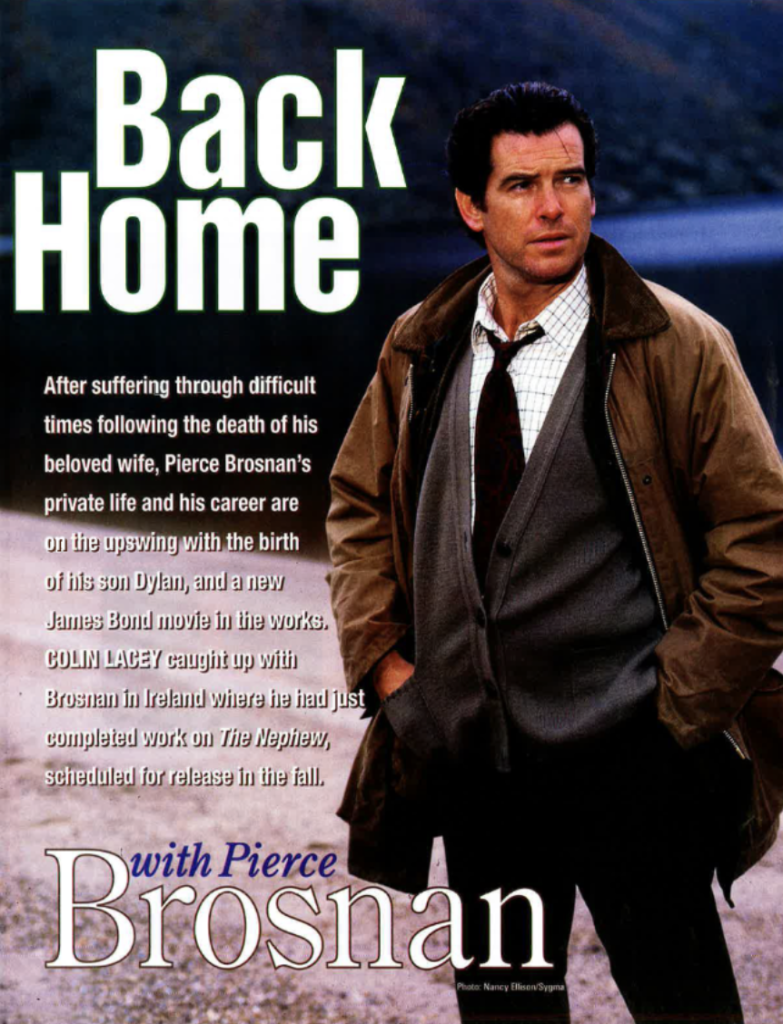

For three days now, 70mph winds and vicious rainstorms have bullied the eastern coast of Ireland into a state of rain-saturated submission. Over the weekend, local news bulletins have become little more than official damage reports: a roof cleaved from a house near Rathnew, fishing boats fractured against the pier in Arklow, the lowest parts of low-lying towns plunged beneath feet of water, and no end in sight. It’s the kind of weather bedlam that gives mid-winter Ireland a bad name. And worse — forecasters on national radio are warning conditions will deteriorate throughout the day.

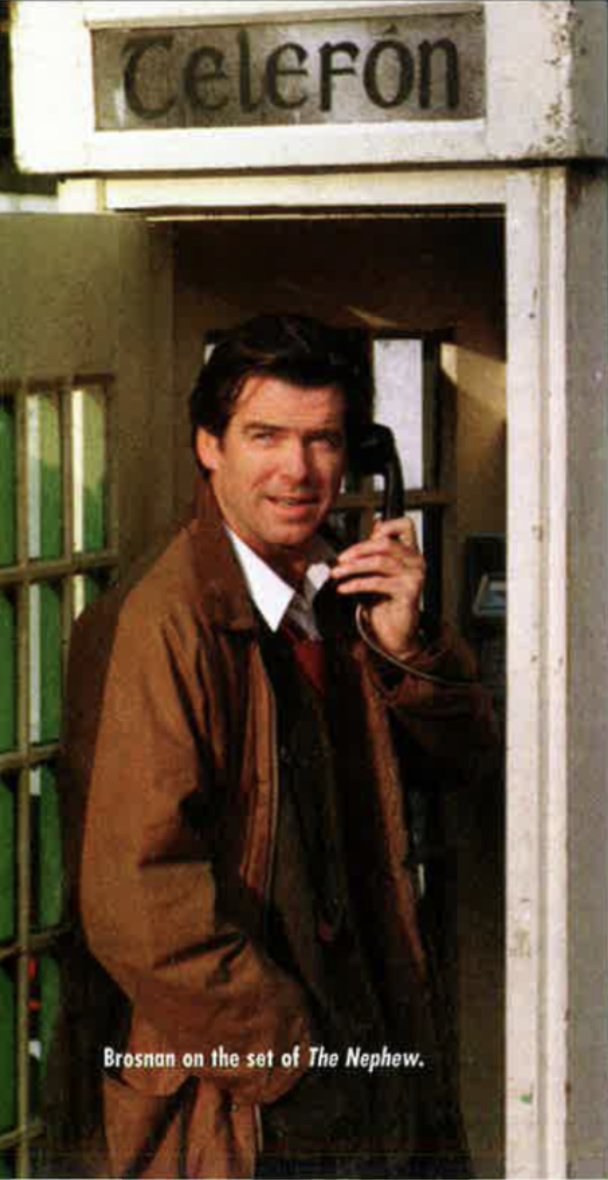

Two miles south of Wicklow town on a rented cattle farm, this is bad news indeed. It’s the first morning of the final scheduled week of shooting on The Nephew, the $4 million debut film of Pierce Brosnan’s production company, Irish Dreamtime, and the way the weather is misbehaving, it looks like it’s going to be a very, very long seven days.

Seen in less uproarious conditions, the set for today’s shoot probably made very happy people of the location scouts on The Nephew. An exposed, 700-square-foot tongue of land poking nervously out into the Irish Sea, little Wicklow Head is probably one of the most camera-friendly sights in the country, and with a realistic-looking, thirty-foot-high dolmen added for the cameras, the place just reeks of atmosphere. But this morning, after trucks, tractors, mobile camera cranes and almost seventy crew and cast members have hiked, waded and lurched through a maze of enclosed fields (a hand-written notice on one gate warns, “Beware: Bull Loose With Cattle”), the pint-sized peninsula is a swampy, sorry island of mud.

And it’s almost impossible to work here. Director Eugene Brady has, for what seems like the entire morning, been trying to set up a simple crane shot beneath the dolmen, but with the gale distressing the camera and the skies darkening by the minute, he is getting nowhere, slowly. The crew and the actors — including Donal McCann, Niall Toibin, and Sinead Cusack, all sheltering together in the back seat of a small car — are very wet and very tired and very cold. Brady is too, and you can just tell everybody is wondering where the fabled glamour of film making has gone and how much nicer it would be to wrap for the day and leave the wind and rain to fight amongst themselves.

Into this teeming disorder strides Pierce Brosnan, smiling and affable, from a truck that looks like it’s recently taken a mudbath. Despite his fiat tweed cap, heavy raincoat, kneelength boots and a python-like woolen scarf, he is immediately, unmistakably identifiable, and the first thing you think is, how does this guy do it? Soaked by rain, half-frozen by wind, and shouldering responsibility for a budget large enough to cripple his fledgling company before it’s even learned to walk, he looks as if he’s just this minute stepped out of a health spa operated by angels with advanced qualifications in tanning and relaxation techniques. Calm in the eye of the storm, he takes in the situation with a concerned, proprietorial air, then greets the camera crew and moves to what’s laughably called the `comfort area’ to hand out cups of hot chocolate and coffee to anybody within reach.

Some women nervously request a photograph. Without batting an eyelid, Brosnan gathers them around him in the rain and smiles like they’re long-lost relatives. He poses with them, then digs a tiny camera from deep in his pocket and snaps them right back. He’s been doing this with crew, with locals — with anybody who happens to get in his way, really — ever since The Nephew set up shop in the area almost a month ago. He could be a politician angling for votes. But he looks like he’s actually enjoying it.

Like the whole thing is his baby. By noon the rain on Wicklow Head has become practically a monsoon, and the crane shot — normally a two-hour job, including camera set-up and rehearsal — still isn’t in the can. Anyone not already on set is told via radio not to come near the peninsula; a mini-tractor has already slipped and overturned in the mud and there’s a real danger somebody could get hurt. The 150-foot drop from the cliff edge to the stones below seems to get suddenly steeper.

Shielded from the elements and eavesdroppers by a giant umbrella, Brosnan consults privately with his director and cameraman, and the word filters round that everyone is staying until the scene is finished.

Back at the comfort area, Brosnan is grinning. “The rain is starting to stop,” he says. He isn’t even close, but everybody smiles anyway. He is the producer around here, after all.

It wasn’t at all like this over Christmas 1995 on the southwest Pacific island of Fiji, when the idea for Irish Dreamtime’s first film was hammered out in the sun.

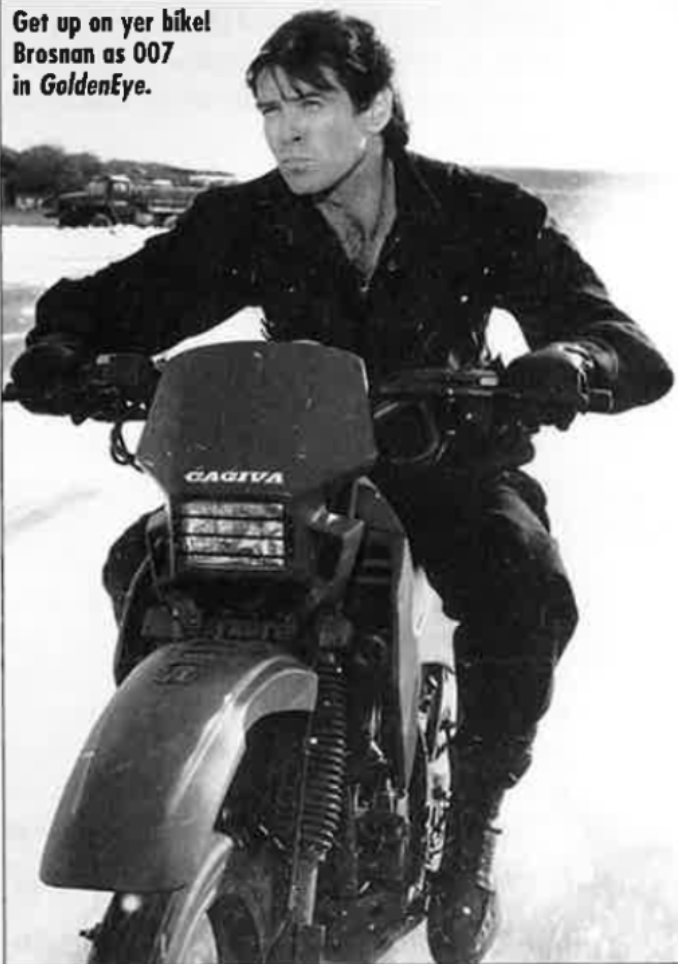

With his debut as James Bond in GoldenEye headed for the record books as the most profitable 007 film ever, Irish actor Pierce Brosnan was looking to consolidate twenty years’ experience and a new-found industry clout into something more substantial than a succession of roles in other people’s films. One of the very few actors to make the great leap forward from television to the big screen with any significant degree of success, Brosnan had been around the block a few times since starring in ABC’s hugely popular 1981 miniseries The Manions of America. He was looking to extend his reach a little, and a production company — which, as well as the risks, offers the benefit of increased control over projects — seemed the way to go.

Together with business partner Beau St. Clair, he formed Irish Dreamtime and began casting about for suitable projects to film. In the Pacific over the holidays, the pair met with Irish film pioneer and industry insider Morgan O’Sullivan, who showed them the script for The Nephew, the debut screenplay from 31-year-old Dubliner Brady. Brosnan and St. Clair loved the unconventional take on the story of a young man’s return from America to discover his Irish roots, and after a round of phonecalls to an astounded Brady, then producing a television commercial in New York, the actor left the Pacific with his behind-the-camera career already out of the starting blocks.

The way Brosnan tells it, becoming a film industry executive was as simple as that. “I’ve been an actor since I was 18 and I’ve been part of Hollywood in one way or another for the past 15 years, so I saw myself as someone who could find a piece of material and say, `I want to work with these actors, this director and create a movie’,” he says, nursing an after-work pint of Guinness and turkey sandwich in a turf-heated Wicklow pub. After continuing through the afternoon until the fading light made further work impossible, shooting on Wicklow Head has mercifully closed down for the day. And the novice producer’s persistence had actually paid off: the scheduled take was finally captured on film.

But at 5 p.m., Brosnan’s shift is only beginning. There are still production conferences to attend, problems to discuss, scenes to be arranged, the next day’s shooting schedule to approve. Beau St. Clair is waiting at the bar with a thick file of papers and a mobile phone, waiting to hear how today’s rushes have turned out. Brosnan is eager to hear the news too. He has only a minor acting role in the film, but says he worked at least as hard on The Nephew as on any of the twenty-odd features he has made since his speaking-role debut as an IRA man in the 1980 British gangster film, The Long Good Friday.

But the difficulties that come with running a production company, like today’s absurdly uncooperative weather, are a small price to pay for the benefits a successful film career has delivered. Indeed, the 44-year old sees his new role as a producer as a way of reinvesting some of the fruits of his success back into the industry.

“The genesis of Irish Dreamtime was to find material, to find young writers and actors and directors and put back into the cinema community, whether in L.A. or in Ireland, a little of what we get out,” Brosnan explains, his voice, despite roaring above the wind all day, slow and soft as honey — James Bond with a dash of L.A. and a sprinkle of Irish slang.

He could recite the menu in a restaurant and make it sound sexy, or at least appetizing enough to order seconds. It’s probably a canny old actor’s trick too, but he rarely rises above a whisper in conversation, and you find yourself leaning toward him, as if every word was an issuance from the oracle.

“We hoped at the beginning to find a project that would be Irish and exciting and a challenge,” Brosnan says, and adds that Brady’s script for The Nephew fitted the bill perfectly. In the film, Chad Egan, a 17-year-old from New York, travels to Ireland to distribute his late mother’s ashes. His uncle, and the whole population of Inishdaragh, the tiny island from which his mother emigrated, are initially shocked to discover that the visitor is black, and Chad is greeted with a mixture of suspicion and curiosity. A search for information on his mother’s departure for America, combined with a romance with a local girl, serves only to dredge up long-buried hostilities and secrets, and Chad’s mother seems destined to remain a mystery until he discovers Uncle Tony has some secrets of his own relating to her emigration.

Brosnan describes the film with great warmth and affection, like a parent itemizing the antics of a favorite child. Coming on the heels of his success as James Bond and a spate of appearances in recent box-office hits — he played a dashing volcanologist in Dante’s Peak, which pulled in an impressive $52 million in its first three weeks of release, and showed up as a mad English boffin in cult favorite Mars Attacks — Brosnan’s first self-produced movie is an important watershed in his career. Success behind the cameras has strengthened the industry positions of leading Hollywood figures like Clint Eastwood, Mel Gibson and Danny De Vito, and Brosnan, who was listed last year for the first time among the 20 most powerful men in the British film industry, could be constructing his own route to similar successes.

After GoldenEye, he has already signed to play Bond at least two more times (the next 007 film, tentatively tided Shatterhand and scheduled for 1998 release, began shooting last January in France), and has a clutch of Irish Dreamtime projects in development over the next several years. One feels that, whatever the reception afforded The Nephew when it is released later this year or early in 1998, Brosnan’s particular combination of charm and determination to succeed will see him remain at the top of the Hollywood pile for a long time to come.

I was made ashamed of being Irish, so I buried my Irishness and I buried my accent.”

All in all, he says, he has come a long way since his boyhood in Navan, Co. Meath, where he was born in May, 1953. Raised by his aunt after his parents separated, he moved to London to join his mother in 1964 (ironically, so the story goes, on the same day Bond creator Ian Fleming died), and attended a comprehensive school there for four years. He quit aged 15, and began a career as a trainee commercial artist in a studio in the London suburb of Putney. An interest in acting came later, but in retrospect, Brosnan believes he actually began acting in earnest as soon as he reached London. It developed, he says, as a simple defense mechanism.

“Starting in London in 1964 I had to create an identity for myself, and I took on the role of a young Cockney lad,” he remembers. “I was made to feel ashamed of being Irish, so I buried my Irishness and I buried my accent. I lived in an exclusively non-Irish area in Putney and was shamed in the school yard by the way I sounded and behaved. I had no one to protect me or to look to. I had to think on my feet and I addressed a lot of the aggression that would come my way, sometimes by fighting, and ultimately with humor. I became a kid from [drops into perfect Cockney] Sarf Lahndan. All my mates were like tha’ an’ I became like tha’. So as time has gone on, I suppose, I’ve readdressed some of that and fought back as an actor as I did then as a young boy. I suppose the seed of acting was there.

“Possibly it was also there as an altarboy in Navan,” he adds. “The first stage I was ever on was serving Mass. I had not at that time any dreams or aspirations to be an actor, but by the time I got into my teens and had discovered films and the whole world of cinema, that then had another added layer for me.”

Brosnan took to acting proper after a workmate introduced him to the theater, and at 18, having had enough of drawing illustrations for British retail businesses, he turned to acting professionally. Success came relatively quickly. Tennessee Williams personally recruited him for a London production of his play The Red Devil Battery Sign. Italian director Franco Zeffirelli offered him a role in another high-profile production, and by the late 1970s, he was picking up guest appearances in prestigious British television shows. A handsome six-foot-one, with dark hair, sea-blue eyes and a sense of composure that marked him as the kind of star a camera likes to linger over, it was only a matter of time before the big time came a-knocking.

His crucial break came in 1980, when he was cast as firebrand Rory O’Manion, the male lead in The Manions of America, the first maim stream American television series to use the Great Famine and emigration as a backdrop. Brosnan still recalls the sense of excitement he felt at landing the role and the opportunity to move to America as an actor. After over a decade in the business, he felt he had finally `arrived.’

“When I got off the plane in America, I felt the greatest I ever had in my life,” he says, smiling. “I remember leaving Heathrow in London on Aer Lingus with a copy of The Great Hunger by Cecil Woodham-Smith under one arm and the script for The Manions of America under the other and this great, great surge of emotion as we lifted off the runway. I thought, by God I’ve done it. It’s my time and I’m gonna take it by the throat and fly, in every sense of the word, with it. Because it was my time to take the anger and the shame of the playground and to put it on film and perform it in a piece about what had been done to this country by the English back then.

The Manions was a bit of a soap, but a lot of it was good, strong stuff.”

The success of The Manions was a major boost to Brosnan’s resume. By now married to Australian actress and former Bond girl Cassandra Harris, he decided to uproot the family (Cassandra had two children by former partner Dermot Harris, a brother of actor Richard) from London and launch a do-or-die assault on the American entertainment industry. Even then, Brosnan’s belief in his own ability to succeed was strong enough to get him halfway there.

“After The Manions, I felt a great sense of strength and knew and hoped it would be a new beginning for me,” he says. “And it was, because when the mini-series came out we borrowed $3000 from the bank manager and went to America for two weeks. I hooked up with an agent there, he had a spare bedroom, we got a car from a place called Rent-A-Wreck, and the first audition I went to was for NBC, who were looking for this character Remington Steele.

“At the end of the two weeks, having traipsed around L.A., banging on doors with my tapes of The Manions, I went back to see the producers of Remington Steele and they asked me to come back. And that was it, I got Remington.”

Remington Steele made Pierce Brosnan a household name. If The Manions of America marked his arrival as an actor, Remington Steele showed he had the range and charisma to attract large audiences on a regular basis. The series ran for 91 episodes, bringing Brosnan’s debonair, wisecracking investigator into American homes at prime viewing time for more than four seasons. Within twelve months of the show’s debut, he was on the cover of People magazine being called “the new Cary Grant.”

He was becoming a bankable star — “America embraced me,” he says, fondly, “and I embraced it right back.” But television is a dangerously fickle medium, and with ratings falling, Remington Steele was cancelled in May 1986. Around this time, rumors began to fly in the entertainment press that the producers of the James Bond series of films were looking to replace aging star Roger Moore in an attempt to reinvigorate 007’s performance at the box office. Brosnan, with his playboyish good looks and a proven ability as both a straight and comedic actor, was an obvious candidate. For his part, the opportunity to move to the big screen as the star of one of the most lucrative movie franchises in the world was hugely attractive. But, in a cruel irony, media interest in the possibility of Brosnan landing the Bond role brought new attention to Remington Steele. Audience figures rocketed — summer reruns of the show reached the Nielsen Top 5 for the first time ever — and the producers decided to bang out one more series, and refused to release Brosnan from his contract. The Bond role in The Living Daylights went to Australian Timothy Dalton (since consigned to the “where-are-they-now” file), and Brosnan had to complete another season on the small screen.

Even now, ten years later, he finds it difficult to conceal his disappointment at the way he was treated, and is characteristically frank about what was then a significant setback to his career.

“I was pissed off,” he says, bluntly. “I was extremely angry. I had wanted to move on from Remington Steele after the first season but I had signed a contract, and I think that once you commit to something and say you want to do it you see it through to the end. There wasn’t much point in stamping my feet and saying, `I’m gonna dishonor this project.’ It gave me a career in America and a wonderful lifestyle and schooling for my children and a home and…it was a wonderful education as an actor to work constantly in front of the cameras.

“But there were men who were behind the scenes who were very `short’ people in many respects, greedy people, and it was hurtful when they said I couldn’t move. I really felt Bond had slipped away from me then. As far as I was concerned it was done. Finished. Move on. Next. Don’t look back. I don’t think it was meant to be back then. There are too many twists and turns — too many to go into in an interview; some day I’ll write them all down myself — but it was just not meant to be.

“I think the Great One up there wanted me to sit tight. I didn’t know at that point I was about to lose a wife, that my life would be changed so dramatically. So I was meant to live through and experience the loss.”

Brosnan is disarmingly candid about the death of Cassandra, who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and died on December 28th, 1991, one day after the couple’s eleventh wedding anniversary. He refers to her frequently, with a casualness that belies the magnitude of the loss. Without becoming sentimental or morose, he softens visibly when discussing her illness and the effects of her death on the children and on himself. But he also appears to draw strength and composure in the retelling.

“Losing Cassandra affected me profoundly, in many ways, forever,” he says, without pause. “The loss was very great, and Cassandra is forever with me and in my heart. But you move on. You live on. There are things to do.

I have a life to live and children to bring up, and I wish it hadn’t happened, but it did. It happens to people every second of the day. It’s just that being a public figure, it was written about and in some ways many great things have come from it. I have a daughter that lives under the mantle of ovarian cancer, which my wife died from, and that is a terrible thing to have in the back of your mind when you’re growing up.

“I’m Catholic, and I have a good faith that carried me through my wife’s diagnosis and illness, but you do fear death. You find a partner whom you love, somebody who is beautiful and you step out into life with, and then you watch them struck down by this disgusting, insidious disease. It’s very, very powerful.

“But you get an incredible gift when you see someone you love die. As terrible as it is, it’s a profound thing to share, and I give thanks every day for the good fortune I’ve had. I still light candles occasionally too — once a Catholic, always a Catholic!” Cassandra’s illness and death were devastating, but Brosnan refused to let the loss overcome him and his family. He continued working while he raised the children (Charlotte and Christopher, Cassandra’s children, took Brosnan’s name early in the couple’s relationship, and a third child, Sean William, was born in 1983), and, quietly, behind the scenes, became involved with a range of charities for cancer victims. Like Cassandra, he is also a strong supporter of environmental causes.

“I found a voice, in some respects, for women’s healthcare, and I will speak up, stand up and be part of any organization that is trying to do their best to address that,” he says. “You really have to try to know yourself in this business and keep it as simple and pure as possible.

“Because you can be led down many avenues with the glory and the glitz and the glamour and the backslapping. But at the end of the day when you go home, you just have your own worries and troubles to deal with.”

After the Bond/Remington debacle, it looked like Brosnan’s chance for big-screen glory had slipped away. And when his wife’s death made him a single parent with three children to maintain, his primary concern was simply to keep working. He sailed through a series of roles in now-forgotten features and TV films — including melodramas like Mister Johnson, Victim of Love, Death Train and 1992’s execrable sci-fi thriller The Lawnmower Man -without making the kind of impression he had seemed capable of a decade earlier. But a role in the Robin Williams-Sally Field crowd-pleaser Mrs. Doubtfire arrested the decline in quality and when Timothy Dalton stepped down after a second Bond film, Brosnan again found himself heir apparent to the License to Kill.

In 1994, as he was preparing to begin filming a new version of Robinson Crusoe, longtime Bond producer Cubby Broccoli — who had reportedly said, on meeting Brosnan in 1986 that “if he can act, he’s my guy” to take the first available 007 slot — offered Brosnan the opportunity he had earlier been forced to forgo. This time, there were no contractual obstacles in Brosnan’s way, and he was announced as the fifth James Bond at a press conference in June 1994. GoldenEye, the eighteenth Bond movie, cost $60 million to produce and went on to become the biggest Bond movie ever, raking in over $350 million worldwide. Brosnan turned out to be the most popular 007 since Sean Connery’s 1960s prototype. He was — again — a major star.

Naturally, he is pleased with the film’s success and its effects on a career many saw as floundering. But the impression is that Brosnan has more than a lifetime of 007 films on his mind; Bond, as quintessentially English as warm beer and Yorkshire pudding, may only be temporarily Irish.

I am an Irishman – spiritually and creatively and emotionally, I’m Irish. It’s the starting point of my life. It’s given me the strength and the background and the dignity and the grace to be an actor.”

“I’m not sure if I’ve given my `definitive Bond’ as yet,” he says archly, as if such a statement is as ludicrous as it sounds. “It remains to be seen. But I’m contracted for two more, with a possibility of a fourth.”

He emphasizes the word “possibility,” but it’s difficult to imagine Brosnan hanging on to the 007 tag beyond his current contract. For one thing, he has too many other acting and producing projects lined up. And for another, the attention such a role attracts also has its less welcome sides.

Brosnan’s current partner, NBC journalist Keely Shaye Smith, gave birth to their first child, Dylan Thomas Brosnan, in January, amidst a hail of media attention. Although he is well aware that fame and success are double-edged swords, Brosnan is wary of journalists who probe his personal life.

“I’m a family man,” Brosnan says, “and I have been since I was 23. But it’s very difficult right now, because the success of James Bond has sent my life into top gear in some respects. It’s a very important time in my life and I’d like to set the markers now for the later years, so it means I’m working back to back on projects. My two eldest children are very much grown up now, but they still need parenting and guidance and security and confidence and reassurance. My thirteen-year-old is at a very tender age and the success becomes an intrusion into day-to-day living sometimes when you’re out and about and just want some privacy to be with your son….You try as much as possible to keep the two things separate.

“My private life is scrutinized and it can be very bothersome, especially if it’s negative and derogatory. Then it’s very painful and hurtful. I went into the public eye and onto the public stage when I went to America. Cassie and I and the children went there and there was so much attention and we were written about a lot. So it’s hard to backpedal and say `I don’t wish to talk about that.’ But I’m also very proud of my children, and what I do I consider to be a wonderful way of making a living. So it’s not easy. But I try to keep it as simple as possible.”

Brosnan peppers his conversation with frequent references to his children. His stepdaughter Charlotte is studying acting in London, and stepson Chris is a film student in New York. Both are proud, he says, of what he has achieved in his career, and particularly pleased that Irish Dreamtime’s first feature is an Irish movie.

“Charlotte and Christopher’s father was an Irishman, so they have Irish blood coursing through their veins,” he explains, and one cannot help sensing he feels a certain pride in sharing an Irish background with them.

“They adore this country. My younger son, Sean, does too, and it’s nothing that I consciously work on. It’s just there. I’m an Irishman — spiritually and creatively and emotionally, I’m Irish. It’s my roots; it’s my heritage. It’s the starting point of my life. It’s given me the strength and the background and the dignity and the grace to be an actor.”

It was also, he believes, a significant impetus behind the founding of Irish Dreamtime. With The Nephew almost finished, Brosnan is already looking forward to two future Irish Dreamtime productions, the next being a remake of the Steve McQueen/Faye Dunaway classic The Thomas Crown Affair, with Brosnan in the McQueen role. After that there’s a curious project called Mr. Softy, which Brosnan himself developed and describes as “the story of a 50-year-old Teddy Bear.”

Brosnan’s ambitions for Irish Dreamtime are far from limited. He hopes to produce three films over the next several years, and for his company to foster the talents and careers of actors, writers, and directors from Ireland and beyond. Never having had the benefit of a real family as a child, he now finds kinship in the film community.

“The people on The Nephew I’ve known since The Manions of America,” he says. “They know me and they knew Cassie and they’ve watched my children grow up. I never felt part of a family per se, but to be able to coax and cajole and nurture and support and guide, as one does in film, there’s a great satisfaction in that. The world is getting very small, and I think we have to pay attention to each other and look out for each other.”

The next ten years will be crucial for Brosnan’s Irish Dreamtime. But with industry trends favoring smaller, more story-oriented productions, the time may be right for a vibrant new company to make its mark in Hollywood.

Brosnan is under no illusions about the difficulty of making a credible splash in a crowded pool, but knows precisely what he wants from his next decade as a producer and actor.

“I would like to have the same enthusiasm and passion and openness for life that has led me down the road all these years,” he says. “I would like to see Irish Dreamtime spawn the careers of some wonderful actors and directors. I would like to see a body of films to be really proud of.

“And I would like to have hung my hat up as James Bond, and to be growing old gracefully.”

That shouldn’t be a problem. It’s difficult to imagine Brosnan doing it any other way.

Back on Wicklow Head next morning, the storm is still blowing hard. In the converted double-decker bus that serves as cafeteria, smoking lounge and gossip center, the crew of The Nephew are huddled around a small gas heater, waiting for word from above on what time shooting will begin. Nobody says anything, but the way all eyes are drawn to the leaden skies and the rain outside betrays the fact that the prospects of spending another ten hours on the set are unappealing in the extreme. For the crew, at least, it looks as if Irish Dreamtime is about to generate another water-logged, wind-whipped nightmare.

Finally, through the silence, a walkie-talkie crackles enthusiastically to life. “Mr. Brosnan will be ready to go in fifteen,” a man’s voice announces behind a wall of weather-boosted static. “Would everybody please move to the set and take up their positions.”

Nobody budges. Then one crew member, wearing a Braveheart baseball hat and a raincoat the size of a two-man tent, sighs and slowly drags himself away from his seat. One by one, the others follow towards the door. “Mr. Brosnan will be ready to go in fifteen,” the walkie-talkie repeats.

“Ah, good old Mr. Brosnan,” the crew man grumbles sardonically, in a thick Dublin accent.

Behind him, someone has begun humming the Bond theme tune. Everybody laughs. “Good old Mr. Brosnan,” the crew man mutters again as he exits the bus. Then he shrugs his shoulders against the wind, adjusts the collars on his raincoat, and arches one eyebrow exactly as 007 does when facing adversity. The rain has begun falling harder. “Licensed to splatter about in the Wicklow muck,” he says, and disappears into the weather.

Leave a Reply