The Irish have long loomed in American imagination. From Mr. Dooley to Scarlett O’Hara to Randall Patrick McMurphy, they have appeared as powerful symbols in popular American fiction, standing for will power and unbowed determination (in the case of Ms. O’Hara, who would never go hungry again) or for deep-seated sanity and freedom of spirit (in the case of R.P. McMurphy, the Irish-American hero of German-Lutheran acid-head Ken Kesey’s fable of the Sixties, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) or for the slywit and wisdom of the eternal underdog (in the case of Finley Peter Dunne’s Mr. Dooley). But these three figures are only tips of the proverbial iceberg; and I choose them purposely to alert the reader to the pervasiveness of this positive image of the Irish in American literature, so pervasive that it amounts to something of an archetype.

Even in more serious, more “literary” fiction, we find the same archetype at work. To mention but one early example that few are likely to be familiar with, there is a story by Sarah Orne Jewett, the great Maine writer who was born only a few years after the Irish famines began, entitled, “The Courting of Sister Wisby,” which contains an old woman’s reminiscence of her childhood and of “the first Irishman that ever came this way”: “He was a good-hearted creatur, with a laughin’ eye and a clever word for everybody….Fiddle! He’d about break your heart with them tunes of his, or else set your heels flyin’ up the floor in a jig, though you was minister o’ the First Parish and all wound up for a funeral prayer. I tell ye there win’t no tune sounds like them used to. It used to seem to me summer nights when I was comin’ along the plains road, and he set by the window playin’, as if there was a bewitched human creatur in that old red fiddle o’ his. He could make it sound just like a woman’s voice tellin’ somethin’ over and over, as if folks could help her out o’ her sorrows if she could only make `em understand. I’ve set by the stone wall and cried as if my heart was broke, and dear knows it wa’n’t in them days.”

At length, the old woman tells of how Mrs. Foss, a neighbor, was widowed and then lost her three children – “she set the world by `em” – to scarlet fever. The widow’s distraught friends gathered at her house but were all at a lost for words with which to comfort the bereft mother. “Everybody was wrought up, and felt a good deal for her, you know. By an’ by Jim Heron (the fiddler) come stealin’ right out o’ the shadows an’ set down on the doorstep, an’ ’twas a good while before we heard a sound; then, oh, dear me! ’twas what the whole neighborhood felt for the mother all spoke in the notes, an’…Mis’ Foss’s face changed in a minute and she come right over an’ got into my mother’s lap-she was a little woman-an’ laid her head down, and there she cried herself into a blessed sleep.”

So, in addition to determination, sanity, freedom of spirit, wit, and wisdom, we must add that the bewitching power of art – the power to transmute the longings and sufferings of life into symbolic resolution and even comfort – has long been associated with the Irish in the American mind. But I think this cluster of positive associations is something many Irish-Americans, familiar with the racist images of Irish drawn by nineteenth-century cartoonists and the usual accounts of “No Irish Need Apply” and the ancient American prejudices demonstrated during the Al Smith campaign, may be largely unaware of.

Of course, we are all aware of the way in which President Kennedy’s masculine grace and playful wit captured American imagination. Here was a figure in life who might have stepped right out of literature – a figure whose life, and even whose death, seemed more like a kind of story. (I knew his widow, Jacqueline, who was a colleague at Doubleday, and who was fascinated by the parallels between “Jack,” as she called him, and Art O’Leary, the subject of the great Irish poem, The Lament for Art O’Leary, written by O’Leary’s wife, Dark Eileen, aunt of Daniel O’Connell, whose tribute to her murdered husband bears real parallels to Jackie’s extraordinary acts of reverence for Jack: “And your blood in torrents – / Art O’Leary – / I did not wipe it off,/ I drank it from my palms”). Another exceedingly Irish life, which many Americans are familiar with, is that of F. Scott Fitzgerald – the high-style Norman “Fitzgerald” being common to both men. And both men were intensely attractive figures, full of promise, ending in tragedy.

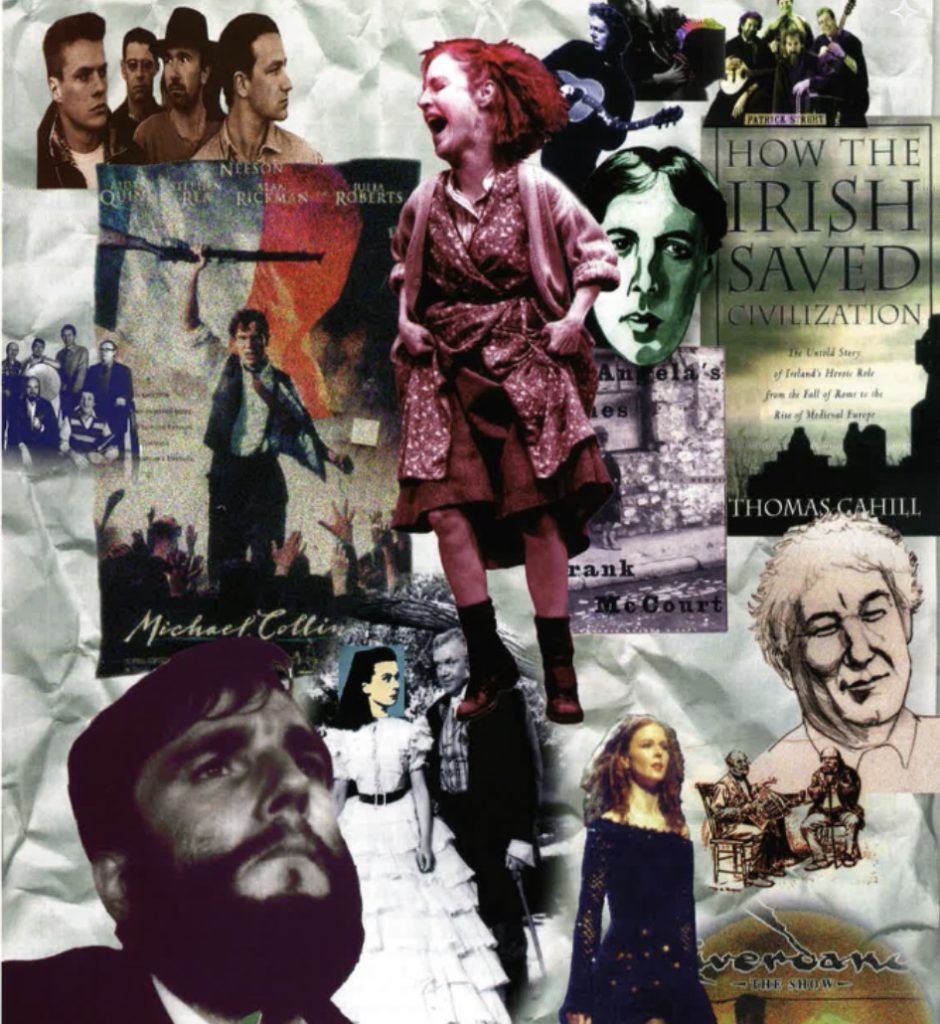

So the archetypes abound, romantic, if you like, but certainly positive – though confined, up till now at least, to fiction and a few comet-like lives that have come to rest as permanent stars in our mythological heavens. All this is about to change. For, in an explosion of creativity, the Irish (and their cousins, the Irish Americans, between whom Americans make little difference), aware at last of the huge reservoir of American good will toward them, are finally making use of that good will in a dazzling outpouring of new endeavors. From dance to film, from music to drama, from autobiography to history, the Irish are suddenly everywhere.

Who did not want tickets to Dancing at Lughnasa? Who does not want them now to Riverdance, about to begin its sensational national tour? Will the droll Broadway production of Oscar Wilde’s An Ideal Husband run forever? How many films in recent years have rivaled My Left Foot for humor and pathos or In the Name of the Father for dramatic impact and political acuity? When was the last time anyone made a top-grossing film for $25,000 (as Edward Burns did with The Brothers McMullen)? What country twice its size has the lineup of major films opening this winter that Ireland is about to bestow on the world (Michael Collins and Some Mother’s Son being just the beginning)? Have you counted recently just how many top box-office stars have Irish last names? (Almost half of them, I’d say.) When was the last time there were two books of Irish interest hitting the best-seller lists (Frank McCourt’s magnificent Angela’s Ashes and my own not-so-humble How the Irish Saved Civilization)? Whoever suspected an Irishman could win the Booker (as did Roddy Doyle, that master of the spoken word and the secret thought who will soon see the premiere of the third film to be based on one of his hilarious “Barrytown” books)? Nor in this stellar lineup can the massive figure of Nobel prizewinner Seamus Heaney be forgotten.

When it comes to music it’s hard to know where to start. The outsized success of two Celtic (largely Irish) record labels, Seanachie and Green Linnet (which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary in a grand hooley at The Bottom Line), featuring the sounds everyone is listening to from Altan to Patrick Street to Niamh Parsons to the monks of Glenstal Abbey, would make old Jim Heron proud. And if he could hear The Cheiftains’ new album, Santiago (a genuine Celtic revelaton that I predict will take off like greased lightning), he’d pop his buttons. Celtic music, astonishingly popular everywhere, is quickly becoming a kind of new international language.

Even a mid-sized American city like Milwaukee (population 600,000) has its own sprightly Irish newspaper, The Irish-American Post (circulation 25,000), an Irish Culture and Heritage Center (harbored by a Congregational church where Calvinist ghosts are surely being made to endure exceedingly distasteful scenes of wild dancing and general merriment), and an annual Irish Fest that attracts more than 115,000 visitors each summer, supporting the boast that it is “the largest Irish cultural event in the world.” When I was on a book tour last March, I spent a glorious evening in Milwaukee at the Black Shamrock pub, which features weekly poetry and drama readings and nightly sessiuns with impossibly fine young Irish musicians (Irish in that they’re playing Irish music; ethnically, they’re as diverse as America), most of whom got their initial inspiration as volunteers among the thousand or so that the Fest recruits each summer from local high schools. As I left the pub that night, I was told that Milwaukee had six other Irish pubs of equally high quality!

As our stages and screens and bestseller lists become crowded with more and more Irish offerings, as scenes like those at the Black Shamrock are played out every night in cities throughout the country, we have truly reached the Irish Moment, a moment of unparalleled influence in America’s (and perhaps the world’s) imagination. It was Clarence Darrow, the great public defense attorney, who long ago said that he always hoped for Irishmen on his injuries because they of all human beings could be counted on to be compassionate. May we use this moment to continue to articulate the compassion that has always been the hallmark of the Irish soul.

Leave a Reply