She came from the west of Ireland, an earthy and fearless convent girl who went on to be the most sensual, sexualized character in 20th Century fiction, Molly Bloom of Ulysses, a book she never bothered to read. When asked if she was the model for Molly, Nora huffed, “No, she was much fatter.” But she was Molly, and she knew it.

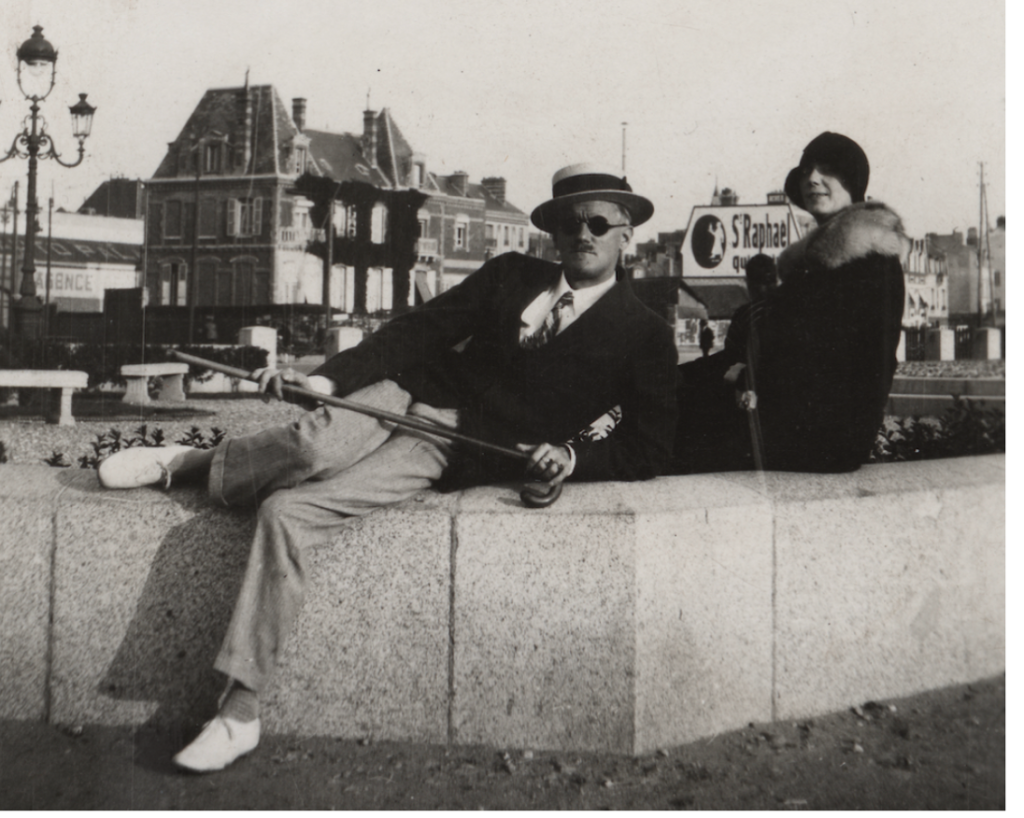

Nora Barnacle was 20 when she arrived in Dublin and met James Joyce in 1904. She had run away from Galway, her absentee mother, her strict uncles, and her friends, without goodbyes. She began work as a chambermaid in Finn‘s Hotel. Nora and Jim spotted each other on Dublin’s Nassau Street. Noting his nautical cap, canvas shoes and long frame, she thought he must have been a Swedish sailor. Rather he was a myopic, 22-year-old university graduate, recently returned from Paris who was developing, in Dublin, a reputation as a gifted writer.

Joyce was immediately drawn to Nora, especially her erect carriage (he later said, “she walked like a queen”), her proud strut and her gorgeous mass of auburn hair. A devotee of Ibsen, he was gobsmacked when he heard her name, Nora, the heroine of The Doll’s House! It was love at first sight.

Shocking for the time, they struck up a conversation and made a date to see each other, June 16th. Shocking even today, after they strolled to the harbor, Nora immediately unbuttoned his trousers and began fondling him. With this incident, Joyce claimed, “she made me a man.” His limited sexual experience had been confined to prostitutes, and she was, by all accounts, still a virgin though sexually assured. But she knew what she wanted (him) and, sensing his sexual hunger, knew how to get it. He immortalized the encounter by making June 16 the day Ulysses takes place, a day universally known as Bloomsday.

Days later, he asked her, “Is there one who understands me?” She said she did, and it was settled. A mere three months after the night at the harbor, they left Ireland to start life together on the Continent. How reckless it was for Nora, a churchgoer, to run off with a man at open war with Catholicism, a man who held marriage in such distaste that she knew they would never marry, and a man who had yet to tell her he loved her. She noted, too, that Jim enjoyed the drink, often getting, as he would say, ‘peeloothered’ and the rare times he came into money was extravagant, presaging a life of poverty. Always unflappable, Nora was confident the elopement would work, and she was right. They stayed together, monogamous, nearly inseparable, for the next 37 years.

Nora and Jim borrowed all over Dublin to raise money for their self-imposed exile. Jim had a big sendoff at the boat, but Nora stayed hidden. John Joyce, the father, knew his son was leaving Ireland but unaware he was accompanied by Miss Barnacle of whom he did not approve. When the drunken spendthrift heard her last name, John Joyce conjured up a clinging crustacean, warning, “She’ll never leave him.” Even the kind-hearted brother, Stanislaus, said that Nora “had something common about her lips.” Dublin’s Irish Literary Renaissance, spearheaded by Yeats and Lady Gregory, were likewise snooty to the Galway girl, perceiving (incorrectly) that she was simple and probably illiterate.

No one heard what Joyce heard, her lyrical life stories and Irish colloquialisms, Nora was to become his “portable Ireland,” the muse that inspired Gretta from The Dead, Bertha in Exiles and most famously, Molly Bloom. He was a Dubliner, she was from Galway, she was the “other half of Ireland soil…” Jim once wrote to her, “Wherever thou art shall be Erin to me.”

After brief stops on mainland Europe, they set up household in Trieste, Austria-Hungary, Joyce teaching at a Berlitz school during the day and writing at night. Nora was homesick and unlike Jim who spoke several languages, she was oblivious to the lingua franca, Triestine Italian. She would stand silent while he entertained his new friends and drank too much. Nora hated the heat, thought the food too oily and the people, rude.

Three months after they left Dublin, Nora was pregnant. Both she and Jim were happy with the news but ever needy, he wrote Stanislaus urging him to read books on midwifery, somehow thinking that would help. No help needed since Nora easily delivered Giorgio in 1904, a healthy, unbaptized son.

It was a life of relentless poverty for a young couple with a baby. They were evicted frequently and shades of Joyce’s peripatetic youth, moved constantly, an endless succession of rented rooms, flats, friends’ homes and the odd hotel stays. Their dire circumstances forced Nora to take in laundry. But she learned Italian.

Two years after Giorgio came their daughter Lucia. After having her baby in the pauper’s ward, Nora returned home to find Jim lying in bed with rheumatic fever. Desperate, he got Stanislaus a job at Berlitz, enticed him to Trieste and live with the family. Nora, knowing Stanislaus found her beneath Jim, was at first aloof to her common-law-brother-in-law, flaunting her Italian. But she soon appreciated Stanislaus especially his salary, which went directly to support the family.

She needed the money: the Joyces lived way beyond their means, always dining out, leaving lavish tips, going to the opera and indulging Nora’s flair for fashion. Truly, they had style, charm and charisma. Their sense of fun and celebration was evident in their many parties, usually with music. A gifted tenor, Jim sang, and Nora played the raconteur, together they were known, lovingly, as “the Irish couple.” The Joyce family of four lived on top of each other which suited them all, through the years they were always together moving through Europe like a single cell organism.

In 1909, the Joyces had a rare separation. He returned to Ireland to meet with his publishers and to pursue a quixotic business scheme—a foreign cinema in Dublin. Once away from Nora, he developed an abnormal fear of being cuckolded and was consumed with morbid jealousy. Nora, too, was troubled, worried that he might resume his youthful brothel visitations. She initiated their famous “dirty letters,” their erotic, pornographic and often, scatological, letters. Besides being “pornosophical” (a Joyceism) the letters were also romantic, poetic, and funny. Nora was his equal in the fueling and fouling of desire, Jim wrote, “Your letters are worse than mine.”

Brenda Maddox, author of Nora: The Real Life of Molly Bloom, finds the roots of Molly Bloom’s interior monologue in Ulysses in Nora’s unpunctuated, epistolary style. She may have been absolving herself when, later in life, she claimed, “I don’t know whether my husband is a genius or not, but he certainly has a dirty mind.”

World War I broke out, the Joyce’s British passports put them on enemy soil, forcing them to leave Austria for neutral Switzerland. They arrived in Zürich in 1915, a time when Dubliners and Chamber Music had been published, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was being serialized and Jim was getting famous. More importantly, he attracted wealthy patrons, including Harriet Shaw Weaver. Still they were penniless, Nora as feckless as Jim with money. She outfitted the family (and herself) with new, elaborate wardrobes every season. But even prim, Protestant Zürich took to the “Irish couple.” Nora and the children had many friends while Jim devoted himself to creating modern 20th Century literature, writing Ulysses.

By 1917, their financial good fortune continued but Jim, always suffering poor eyesight, now had glaucoma and iritis. Nora was forced to be his secretary, a job she despised. It was around this time Lucia began to exhibit signs of the mental illness that would dominate the rest of her life. Still Jim found time to direct Nora as Cathleen in a local production of Synge’s Riders to the Sea. She proved, unsurprisingly, to be a natural actress who used her rich, strong voice to great effect and got rave reviews.

When WWI ended the Joyces planned to re-locate in Trieste but Ezra Pound, now becoming a force in Jim’s life, convinced them to come to Paris. On July 19, 1920, they came for a brief visit and stayed for the next 20 years. On one of their first nights, Pound had arranged a soirée so the Joyces would meet the intellectuals of Paris. It was that night Jim met the second most important woman of his life. “So this is the great James Joyce,” Sylvia Beach said in her American accent, and the following morning he was at her bookshop, Shakespeare and Company. She would be the first person brave enough to publish Ulysses. He still had yet to meet his British patron, the third most important woman, Harriet Weaver Shaw. Miss Shaw, knowing he had relocated to Paris, sent him her recent inheritance to get settled.

Nora and Jim went through Miss Weaver’s gift quickly. After meeting them, Ernest Hemingway cracked, “The report is that the family is starving but you can find the whole Celtic crew every night at Michaud’s.” On February 2, 1922, Joyce’s birthday, Sylvia Beach and her partner Adrienne Monnier handed Joyce a bound copy of Ulysses.

The Joyce family now moved in international literati circles with TS Elliot, Peggy Guggenheim, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Djuna Barnes. It was a drinking crowd, and Jim drank more than ever, often needing to be carried home. A furious Nora once met him at the door, “Well here comes James Joyce, the writer, drunk again, with Ernest Hemingway.”

Over the years, she had threatened to leave him, take the children and, worse, have them baptized, but she always stayed. In 1922, Nora, against her husband’s wishes, made her first trip to Ireland since her exile. But her timing was unfortunate, Ireland was in the middle of a Civil War and when she was on the train to Galway gunfire rifled her car. She left soon after, she never saw Ireland again.

Ulysses, the “dangerous book,” called, alternately, a masterpiece or filth, had made James Joyce famous. While her husband was being both glorified and vilified, Nora was coping with Giorgio and Lucia and their respective chaos. Giorgio had taken up with a married woman 11 years his senior, a rich Jewish New Yorker, Helen Fleischman, who happened to be Nora’s close friend. Nora was losing her favorite child, Giorgio, to…her galpal! But the situation with Lucia was worse.

The Joyce family dynamic was divided along Oedipal lines, Nora doted on Giorgio, Jim was besotted with Lucia. This became painfully evident as Lucia’s mental illness raged, she became estranged from her mother as her father showered her with gifts. In Paris, Lucia had studied avant-garde dancing, showed promise but after she was only a runner-up in Paris’s International Festival of Dance, she quit dancing and put all her energies in seducing her father’s secretary, Samuel Beckett. Nora encouraged the relationship believing it would bring stability to her daughter’s life.

When Beckett explained to Lucia that his visits were only about her father, she lapsed into a catatonic state. Le tout famille exiled him, wrongly believing young Beckett had led Lucia on. This was a particular hardship for Jim working now with only 10 percent of his vision; he needed Beckett as he was in the middle of his most ambitious epic, Finnegans Wake. Only Beckett saw Joyce’s radical intention of “grinding up words, crossbreeding them and marrying sound with image.” They reconciled after Beckett was stabbed by a pimp and seriously wounded. Nora took charge of his recovery and brought him his favorite Irish dishes, custard pudding and colcannon potato cakes.

Lucia worsened. Friends and relatives tried to help, taking the troubled girl into their homes but the trips always ended in disaster. Lucia was violent, given to fits of hysteria and pyromania and causing public scenes in London, Paris and Ireland. Everyone but her father knew she needed to be institutionalized but he refused, assuming responsibility, “Whatever spark of gift I possess has been transmitted to Lucia and has kindled a fire in her brain.” When she was finally committed, Nora wasn’t allowed to visit Lucia, her very presence was deemed a trigger for the schizophrenic daughter.

On July 1, 1931, Nora and James Joyce married in London. They did it for “testamentary reasons,” to secure the estate for the children and future descendants. A few months earlier, Giorgio and Helen Kastor Fleischman married, a union that still troubled Nora. For a lesser mortal, it all would have been unbearable: her daughter was going mad; her husband was going blind, and her beloved son had married an inappropriate woman. But Nora persevered and kept the family together, she was both resilient and practical.

When Jim started Finnegans Wake, Nora complained to her sister, “He’s on another book again,” then complained to Joyce that he was keeping her awake, writing and laughing at this own jokes. It took him 17 years to write the book in a language of his own invention, it was his most opaque, obscure work, disappointing his loyal readers. Not so Nora: Finnegans Wake was her favorite of all his work, she read it cover to cover. (It’s been noted that Ireland’s two greatest prose writers of the 20th Century chose to shun the language of the conqueror, Joyce by creating his own language, Beckett by writing in French.)

In 1932, Nora and Jim were over the moon when Helen and Giorgio had a son, Stephen James Joyce, the descendent who would carry on the name of Joyce. They adored their grandson, spending much time with Stephen but mental illness struck their lives again. Giorgio’s wife, Helen, was diagnosed with manic depression and her erratic behaviour landed her in jail and a sanitarium until her family took her back to America. Giorgio, now drinking heavily, took Stephen to live with Nora and Jim, the child bringing much-needed joy to their lives. But, in 1939, Hitler marched into Poland.

The Joyces left Paris in the autumn of 1939 with Swiss visas for all but Lucia who was denied an exit permit, so they resettled in Zürich without her. On January 13, 1941, following an operation for a perforated ulcer, an ulcer he didn’t know he had, James Joyce died at the age of 58. Though Nora had returned to the church, she refused to give her husband a Catholic burial. Edna O’Brien said Joyce’s finest epitaph came from his widow who, after his death, wrote to her sister, “My poor Jim, he was such a great man.”

Nora lived for another ten years without him, daily visiting his grave. She couldn’t access Jim’s resources because of the war forcing Miss Weaver had to smuggle her money though it was illegal. Many of the intellectuals who worshipped her husband shunned Nora having now decided, after enjoying many evenings of her hospitality, she was “vulgar.” Giorgio, who managed to never work a day in his life, descended into alcoholism. Helen Joyce, now recovered, brought Nora’s grandson back to America in 1945, further saddening Nora’s final years.

In 1948 the Irish Navy brought Yeats body back from France, to have him interned, with a state funeral, in Ireland. Nora contacted the Irish embassy suggesting a similar honor be bestowed on James Joyce. De Valera’s puritanical government coldly rejected her and her pornographer/blasphemer spouse. Times have changed: today Irish tourism monetizes and revels in Joyce; Bloomsday has become a worldwide celebration, its capital is Dublin. And his body still remains in Switzerland.

She died of heart failure on April 10, 1951, and was buried with her husband in the same Zürich cemetery. In the 73 years since her death, she’s become, not unlike Queen Maeb, an icon of Celtic womanhood—brave and headstrong and with a healthy libido. Nora Barnacle Joyce’s invaluable contribution to world literature—she sustained and inspired its greatest artist—should never be forgotten.

Epilogue

Giorgio Joyce lived in Germany until his death in 1976. Lucia Joyce died, still institutionalized, in 1982, outliving all her immediate family. Nora’s grandson, Stephen James Joyce (one must use all three names), became the executor of his grandfather’s estate and was reviled as a wildly litigious, greedy jackass. It’s generally agreed he held back Joyce’s scholarship for decades. Worse, Stephen James Joyce defied his grandparents’ wishes to have descendants by remaining childless, once declaring, “The line dies with me.” This would have saddened even the redoubtable Nora.

Leave a Reply