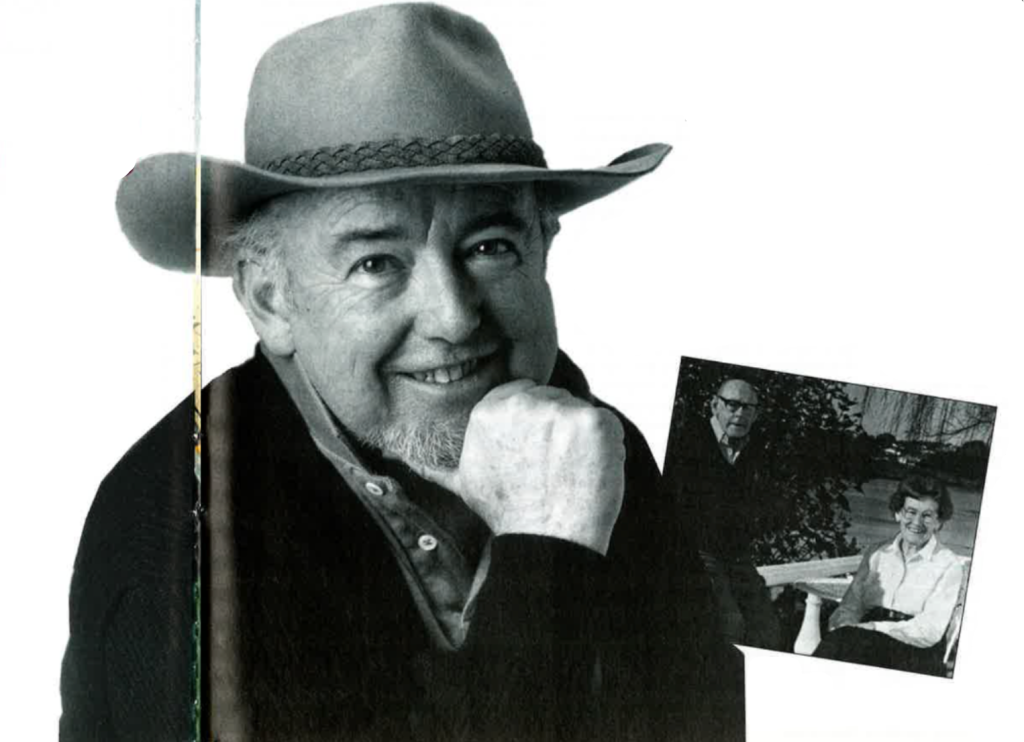

Thomas Keneally is one of the world’s great writers, an Australian who has revived the literary tradition in a country better known for shrimps on the barbie than the strength of its intellectual tradition.

Schindler’s List was the book which made Keneally’s worldwide reputation, but long before that he had solidified his Australian roots when he explored the differences between the white and aborigine cultures in The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith, like Schindler’s List made into a successful film, and examined his own Irish Australian upbringing in Homebush Boy.

In his latest work — which he completed this Fall — he chronicles the role of the Irish deportees in shaping Australia.

Keneally lives outside Sydney in the suburb of Manly, hard by the Pacific ocean in a wonderful house overlooking a beach that Hollywood directors would die for. His home is reached via an exquisite boat ride across Sydney Harbor, one of the grandest sweeps of water on earth, now full of pleasure craft, but in the 19th century it was the first sight of land for the transported wretches after months at sea.

Keneally displayed the great hospitality and warmth which is second nature to Australians, taking time to show a stranger his native city from several vantage points along the Manly shoreline, then sitting round the living room table with his charming wife Judy and two daughters, dissecting the world at large and the Irish role in it. Every so often he jumped up to watch the progress of a rugby league game on his television — he is passionately committed to his native Manly side.

Later we slipped away to his cramped work studio where, in the course of a lengthy conversation, he ranged expansively over Irish Australian topics, including his new book, which is based in part on the story of his wife’s relative who was transported to Australia in the last century. Though he spends lots of time in the U.S., Ireland and elsewhere, Keneally is the quintessential Irish Australian — an identity similar to Irish American, but different in key ways. We began our interview on that topic.

Irish America: In your book Homebush Boy there is an extraordinary section on the education given by the Christian Brothers here in Sydney. Reading it, it seems like the Christian Brothers’ upbringing was the same worldwide. What does that say about the Irish upbringing?

Thomas Keneally: It says that beneath the general oppressive umbrella of the British Empire there was another flourishing empire. The Irish let them have the real estate, but the Irish had something more permanent, something they really believed in, the rites and sacraments. There’s an Australian journalist, Phyllis Knightly, who was raised in Southern India by Irish nuns, and her soul is identical to mine. The only question the Irish have to ask themselves is whether to be proud of this potent worldwide effect of Irish Catholic education. I think it inevitably produced a sense of social engagement, worrying about the world, worrying about equity. I think the missionary impulse grows out of that tradition. The idea is that there’s something that produces positive social engagement through attending a Catholic school. It’s not always true, and one should not over-sentimentalize it. It’s not what the nuns and brothers thought they were doing, but they did.

We started by caring about black babies. My wife, Judy, used to shoplift the chips at the pictures, which gave her a spare three pence to sling to the black babies. Though nicking a bag of chips was a venal sin, redeeming black babies put you in the big leagues.

IA: Many of your books, including Schindler’s List, deal with the topic of the underdog. Your new book, about the Irish penal colony in Australia, does too. Why do you identify with underdogs so much?

TK: First of all, it’s because I wasn’t a tough kid. In an overt sense I don’t think I’m a tough human being at all, like most novelists. Most novelists are pushovers, they get depressed easily, they get defeated easily. I feel that in the Australia of my childhood we had a culture of loyalism, a culture of Britishness, but Australia had Irish Catholics too who didn’t quite identify. My formative years were spent before the arrival of the Poles, the Italians and the Greeks here. The massive explosion of immigrants was post-World War II. Australia was like Ulster in the southwest Pacific and remained fairly monarchically British until modem times. You had a great deal of anti-Catholic prejudice, and feeling that prejudice and then experiencing the tribalism to which you retreat in face of that prejudice is a potent experience.

Judy remembers going for a job in a bank when she was a kid and being told by her father not to wear her hair like that because she looked too much like a convent schoolgirl. That was a Catholic father. As deplorable as that sectarian divide was, I think it gave me a sense of what it was like to be a Jew in Poland. The experience of being on the margin was one I felt very much. This sense of embattledness has meant that I’ve written about embattled people, but it’s not a new phenomenon. In America, there were many Jewish writers writing about the same thing, and some Irish writers.

IA: A Jewish writer I know said that you got the Jews right in Schindler’s List, much like Leon Uris got the Irish right in Trinity. How did you do that?

TK: I don’t know. Schindler’s List was very much from the records, and from the living voices of survivors and others who were involved, so nothing was made up. That probably helps tremendously. The arrangement of material is a construct of mine, and the language or prose, but the dialogue is from eye witnesses or written records. I think it was a sensibility into which I was partially primitively keyed by the Australian experience.

IA: Let’s talk about that. You’ve written about the aboriginals, the Eritreans, the Jews, down-trodden people, and now your current book about the penal colonies is said to be a great Irish book.

TK: It’s also a great Australian book — great in the sense that it’s a bloody big book. It operates from the conviction that Australia was the gulag of the 19th century. It was a pretty pleasant gulag, of course, at least for gentleman prisoners like the Young Irelanders Smith O’Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher, it was better than a prison in Britain or Ireland. However, these people are not known in Australia. That stems from a very inadequate sense in a society which still, sometimes, when it’s looking to reassure itself, will invoke Britishness. But these Irish men and women were often aided by Australians who were progressive and democratic — they were English, Scottish or Irish but they considered their Australian-ness the primary definition of who they were. So in a way, this book is subversive on an Australian level, and that’s one of the reasons I wrote it.

IA: What does it say to Australians? Here is your history?

TK: That’s right. And it says here are people who were oppressed because they weren’t halfway up the monarchical ass. It’s never ceased to fascinate me since I was a kid that Ireland is the only nation in Europe whose population is roughly a bit more than half of what it was in 1841. In 1841 the population was 8.2 million, now it’s about five million. Between the 1830s and the 1880s, by which time the last of the Fenians had escaped from Australia or been liberated, you had a halving of Ireland. I think that created a culture of loss in Ireland and I think Ireland is, in a sense, a traumatized nation, the ways the Jews are a traumatized people.

People always refer back to history for justification, but only in situations where they felt squeezed, deprived, surrounded, besieged or stripped of their rights.”

IA: You wrote about the absent people in Ireland in Now and in the Time to Be, about driving through the countryside at night and seeing the dark hillsides where once there were lights and houses.

TK: Yeah. The big debate about Irish history and the Famine reminds me about the big debate over what to do with the Holocaust. Can you even write a book about it, or who should write a book about it? What should be said about it? Should you say there was a German like Schindler who saved an entirely finite number of people? The uneasiness, as soon as you begin to write about the Holocaust, is like the uneasiness and tormented state of the condition which attaches itself to writing about Irish history.

The Irish, having been through all they’ve been through, are now tormenting themselves about whether they ought to write about it, which seems to me an unnecessary torture.

IA: Should they write about it?

TK: Yes, they should write about it for this reason. I don’t think I’m being glib when I say that in Australia and America you have Armenians living next to Turks without falling on their throats all the time and getting vengeance for the Armenian massacre. Very few people sacrifice prosperity and freedom to settle an old score. I believe that, despite the references to history, the situation in Northern Ireland is about present paranoia, or paranoia carded over into the present. But very much present — present inequities, present perceptions, and [the ideal that history would look after itself if history were settled on the ground. To treat history as the primary trigger of terrorism seems to me not only false but almost laughable. It’s like the argument about not talking about the Holocaust, whether it happened or not, because it will only give right-wing Israelis a chance to beat the hell out of the Palestinians. People always refer back to history for justification, but only in situations where they felt squeezed, deprived, surrounded, besieged or stripped of their rights. In a society where equities operate, you don’t get Macedonians trying to ambush the Greeks. I think the new world is a demonstration of the falsity of the view that history is the cause. History is never the primary cause — it is sometimes justification, it sometimes reaches back to versions of history, but it’s not the trigger. The person pulling the trigger may think that history’s the truth, but, again, we have Serbs and Croatians living in Australia without falling on each other’s throats. What’s happening? Pluralism is happening.

IA: Let me ask you about Irish Americans and Irish Australians. You’ve lived in both cultures, and would be seen as one of the prime interpreters of the Irish Diaspora. What differences do you see?

TK: Well, until recently, the Australians, dare I say, weren’t as overtly sentimental about Ireland, St. Patrick’s Day, etc. Until I was a kid, these things were definitely Catholic festivals and a bit suspect. The problem for the Irish was that getting on in Australia meant that they were not as overtly or sentimentally Irish. But I think there’s a strong inescapable claim Ireland has on them. And, of course, as republicanism advanced on them, and as Australians got older and it became less shameful to have convict ancestors, a passionate interest in [their] Irishness happened. Irish history is now the great industry in Australia. There’s a book, for example, on shiploads of girls sent to convict barracks in Australia from the workhouses in Ireland. They were all found positions, were well fed, well supervised, and became pillars of society. That sort of history is being written a lot now.

I’ve often thought about the answer to Northern Ireland is to parachute half a million really tough Greeks in there. They’d be running the place in no time and everyone would resent them.”

IA: Irish Americans say the election of John F. Kennedy broke the great barrier for them. What was it for Irish Australians?

TK: I think it was just the modern Australia, and the flavor of Australians. It was always easy for Irish Catholics to identify with Australians. The hard thing was to identify with Australia via this constitutional fiction of the monarchy or the Queen being the head of state of Australia, so if you took any office you had to take an oath of allegiance to her. The more that diminished, the more you found people claiming their Irish background. This is something I noticed that people relished when they escaped to America — they felt it gave them a voice. They could say `I’m Irish, I’m here to do what I do, and to hell with the lot of you.’ In Canada, New Zealand and Australia, the Irish were under something of a cloud, because the great chivalry of their society was loyalism. But the Irish were always very visible and active. When the Fenians were pardoned, they came east to get support, and they got massive support. They were always very visible, but always under some suspicion. That suspicion began to die after two world wars, with immigration — with people arriving who got even more up the Anglo noses than we did. They even got up our noses! We found ourselves in a sort of Anglo-Celtic alliance! I’ve always thought what put an end to sectarianism was the arrival of the Greeks and Poles, and I’ve often thought the answer to Northern Ireland is to parachute half a million really tough Greeks in there. They’d be running the place in no time and everyone would resent them. The UVF men and the IRA men would get together for a drink and talk about what bastards the Greeks were. I think that’s one of the benefits of the New World. As sheltered as Australia has been, since World War II we’ve been subjected to an increasing expansion of what an Australian is. Of the kind that the Old Word never is. A kind that Northern Ireland never is.

IA: Do you think Australians’ sense of the Irish is the image of the famous bushranger Ned Kelly?

TK: I think our hero system is identical to that of the Irish American hero. His [Kelly’s] father was an Irish convict: in Kelly’s letters, as much as an IRA man today, he reaches back to Ireland’s historic role as his explanation. He’s also very Australian. His extraordinary magic grew out of the fact that he did all of the right things: he was doomed, and that’s very Irish. The way to get into the Irish pantheon is to say something good and do something stylish. And drink. And if you die on top of that, they give you a statue on O’Connell Street [in Dublin].

IA: So Kelly seemed to capture the essence of the Australian soul too?

TK: Malcolm Turnbull says the Irish won the fight for the Australian soul. What that consists of is anti-authoritarianism and begrudgery but also, far less belief in demigods. Because Australia was founded in what was called the Age of Enlightenment, albeit by second rate British officials and convicts, fundamentalist religion doesn’t have a powerful effect here. It doesn’t have the political power it does in the States. The idea of a Christian coalition setting an agenda for a political party just wouldn’t happen.

I think, in a way, because Ireland is such a profoundly Catholic country, there’s also an Irish cynicism, a sense that we’re not admirers of therapists very much. We go in for getting smashed instead. That’s no more admirable or otherwise than going into therapy. But our anti-authoritarianism means we don’t recognize prophets when he or she arrives. Our cynicism means that we suspect excellence. The Americans believe to a fault that everything is perfectible. That there are answers. In visible terms, it’s in the how-to book. If your girlfriend leaves you, there’s a book to tell you why so that it doesn’t happen again.

I remember a group of American senior students asking me if there was an Australian Dream, like the American Dream. I said yes, but it’s much more modest and pedestrian and banal than the American Dream, because you can be too bloody smart and work too bloody hard and bust a gut. Those feelings of skepticism, of a desire for quality of life on a more modest level, is a profound part of the Australian character. That’s why recreation has been the most important thing to me. I’m a workaholic, but sport is very important and the beach is very important to me. If I were an Irish literary man living tax free, I’d be huge, not only because of the Guinness, but because of the fact that I wouldn’t go on the beach so much and swim.

IA: You are one of the leaders of the movement for an Australian Republic.

TK: I was the founding chair. A lot of people criticized me for being of Irish descent, and said, `Well, what can you expect?’ They said the same of Paul Keating, the former Prime Minister, but I think it would be as wrong to adjust the Australian constitution for Irish reasons as it would be to accept what we’ve got for British reasons. I feel there are pressing reasons for being a republic. One of them is for one’s soul, which would certainly breathe more freely, but that’s true of all the British, Cantonese, Scottish, Croatian, Italian and Greek republicans I know. I was at a republican dance where one of the prizes was a collection of Italian wines put together by an old Calabrian family who are republicans. I like the fact that their action demonstrates that this isn’t an old Fenian plot.

Britain is now oriented into Europe in terms of trade, but the head of state, our head of state…We can’t say, `For God’s sake, go to Strasbourg and speak up for us in matters of trade,’ or `speak up for us in matters of French bombing in the Pacific.’ She [the Queen] can’t do that. So who speaks for us? There are also psychological reasons — believing one’s sovereignty lies 13,000 miles off-shore stroking Corgies.

The other reason is that our main block of trade, our main zone of interest, commerce and influence is going to be in Asia. Those people haven’t forgiven us for the “White Australia” policy. They look for signs of white supremacism in us. They see our connection to a vanquished empire as if a British fleet were out there in the Pacific to protect us from the fuzzie-wuzzies. They see that as a sign of unreconstituted white supremacism. And also they see the fact that our head’s in the wrong place, that we don’t know we’re in Asia. That we’d rather be dealing with Europe but we can’t, so we’re stuck with them. These attitudes from tough Asian governments are destructive to trade and diplomacy, and they’re destructive when we call on them to improve their human rights. So we will have greater authority when we have a republic. I’m also for it for my brothers and sisters of Czech, Croatian and other descent — they’re the power base.

IA: Thomas Keneally, thank you very much.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March/April 1997 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply