The fascinating relationship between Coach Charles Riley and his pupil, the legendary, Jesse Owens, is an engrossing human interest story about a gentle, selfless, Irish American school teacher who became a second father to a disadvantaged Black adolescent. From completely different backgrounds, Owens and Riley grew to love and respect each other at a time of overt racial segregation.

The fascinating relationship between Coach Charles Riley and his pupil, the legendary Jesse Owens, is an engrossing human interest story about a gentle, selfless Irish American school teacher who became a second father to a disadvantaged black adolescent. From completely different backgrounds, Owens and Riley grew to love and respect each other at a time of overt racial segregation.

Charles Riley met the 13-year-old Jesse Owens in 1927 and, during the next ten years, would become not only Owens’ most important athletic mentor but also his second father. They were an unlikely pair to forge one of America’s greatest athletic collaborations. Charles Riley was a short, skinny, bespectacled Irish American who taught physical education and coached track at Cleveland’s Fairmount Junior High School. Jesse Owens was a taciturn, physically unimpressive teenager whose family had moved north from Alabama, where Jesse had worked in the cotton fields. Before meeting Riley, Jesse Owens had absolutely no athletic aspirations and was, in fact, prone to debilitating attacks of pneumonia.

One day in 1927, Riley quietly watched Owens in gym class and recognized in him a spark of untapped athletic potential. Riley asked Owens into his office, sat the young boy down, and thus set in motion one of the greatest careers in the history of American sports: “Would you like to try some running after school?” Riley asked. The perennially shy Owens suddenly perked up: “Sure!”

Owens had a job after school and since his family desperately needed the money, he asked Coach Riley if they could train before school. Riley, admiring the youngster’s determination, immediately agreed to this arrangement. Every morning at sunrise, Riley would arrive in front of the school with his whistle and stopwatch. Riley began by encouraging the skinny youngster to eat more, to build up his strength. Often, Riley took matters into his own hands and brought breakfast for Owens from his own kitchen. Attentive and eager for direction, Owens worked hard for his new coach. Riley taught with quiet encouragement and a gentle, wry sense of humor; he never bullied Owens, and he often made his point by telling amusing anecdotes that made the shy Owens chuckle.

The lessons Riley taught were simple, but they transformed young Jesse Owens’ life. First, Riley stressed the importance of a positive mental approach to running: he told Owens that a good runner uses his legs, but that a great runner uses his head and also his heart. Riley wanted Owens to focus on long-term goals instead of instant results, and thus repeatedly told him that he was not training for some race “next Friday, but four years from next Friday.” Similarly, Riley urged Owens not to worry about what the stopwatch might say or what his competition might do on any given day, but instead to “always run to beat yourself.” Under Riley’s gentle and patient tutelage, Owens began to develop both the physical and mental toughness that would make him a legend.

Additionally, Riley taught Owens the smooth, fluid running style that revolutionized the sprint events. Before Jesse Owens, the dominant sprinters ran with muscular, lumbering strides and wildly pumping limbs; they powered their way down the track with pained faces. Riley’s approach was completely different: Owens would have to run gracefully, and the coach explained this to his pupil in typically colorful fashion. He brought Owens to a racetrack and asked the boy to observe how gracefully the winning horses ran, how relaxed their muscles were and how they showed no strain on their faces. Owens got the message, and he was soon perfecting the smooth, graceful style that sprinters emulate to this day.

Riley’s influence on Jesse Owens went far beyond just athletics: he became the boy’s second father. Owens often ate dinner at Riley’s house, and Riley used these occasions to encourage Owens’ athletic and academic abilities. Riley was the first person to convince Jesse Owens that he could achieve his dreams with hard work and persistence. “I wanted to be like him because he was a wonderful person,” Owens remembered later in life. Owens even began referring to Riley as “pops.”

Owens’ own father, Henry, was frequently unemployed during this period. Increasingly disheartened by the lack of job opportunities for blacks during the Great Depression, Henry Owens worked whenever and wherever he could. He was barely able to buy enough food for his family of ten. Henry Owens was a stoical, emotionally distant father who once told his son that “it don’t do a colored man no good to get himself too high, ’cause it’s a helluva drop back to the bottom.” Jesse Owens badly needed a positive role model, and he found one in Charles Riley.

After training together for a full year, Riley felt that Owens was ready for competition. On weekends, they both packed into Riley’s dilapidated Ford Model-T and drove to local track meets. From the beginning, Owens performed brilliantly. Although still in junior high school, Owens set world records in his age group for the long jump and the high jump. He was also unbeatable in the sprint events. Riley began to realize that Owens’ potential was truly astronomical. The coach introduced Owens to Charley Paddock, a gold medalist in the 100-meter dash at the 1920 Olympics. Awestruck, Owens decided then and there that he too would one day win an Olympic gold medal.

In 1930, Owens enrolled at Cleveland’s East Technical High School. Soon thereafter, Riley was asked to become a track coach at the school. He readily accepted the job, happy to resume daily training sessions with Owens. As a high school athlete, Owens was dominant: a Cleveland sportswriter dubbed him “a one-man team.” While competing as a high school athlete, Owens set world records for the 100-yard dash (9.4 seconds) and the 220-yard dash (20.7). He was beginning to develop a national reputation.

After Owens enrolled at Ohio State University in the fall of 1933, Riley continued to be his mentor. On May 25, 1935, Riley drove Owens to a track meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan. With Riley watching, Owens gave a performance that has never been equaled in the history of track and field. In a span of just 45 minutes, Owens equaled or broke four different world records. At 3:15 p.m., he won the 100-yard dash in 9.4 seconds, matching the world record. At 3:25, he won the long jump, establishing a new world record at 26 feet, 8 1/4 inches. At 3:45, he won the 220-yard dash in 20.3 seconds, smashing another world record. Finally, at 4:00, Owens won the 220-yard hurdles in 22.6 seconds, setting his fourth world record of the afternoon. The crowd was stunned. They mobbed Owens, forcing him to sneak out the back entrance of the stadium, where Riley was waiting for him in the old-reliable Ford Model-T. From that day on, Owens was an international star.

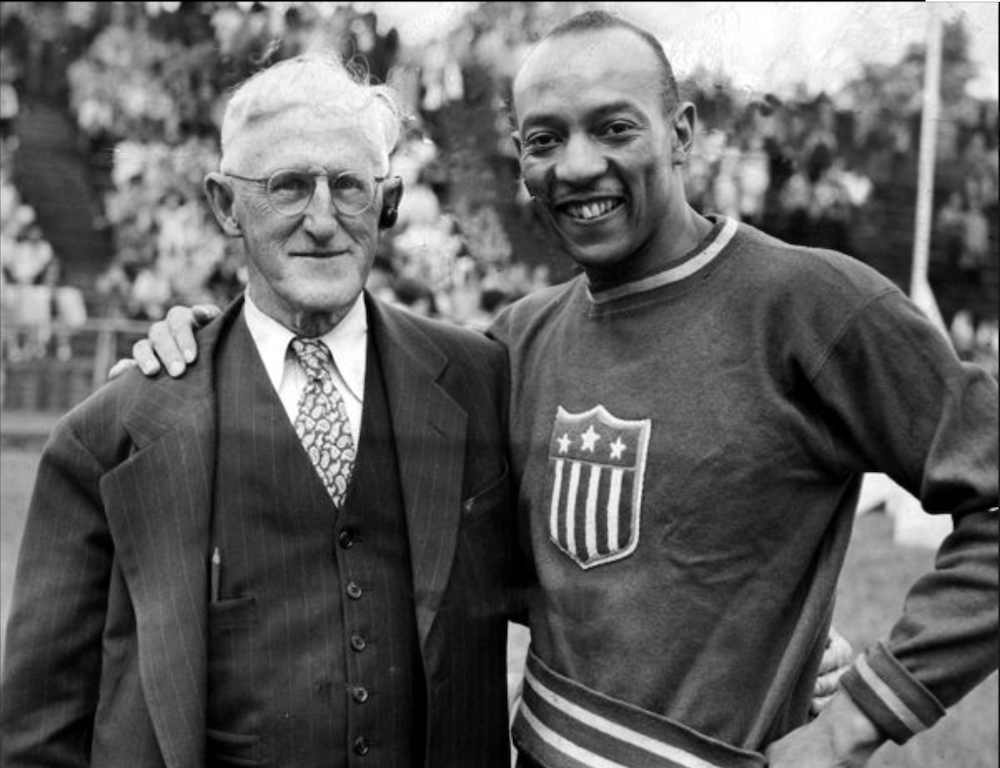

Continuing to train with Riley, Owens easily made the U.S. Olympic team in 1936. Unfortunately for Charles Riley, his meager teacher’s salary didn’t leave him enough money to travel to Berlin for the Olympics. Besides, the coach of the U.S. Olympic track team made it clear that he wanted no “interference” from outside coaches. However, after nine years of constant training and encouragement, Charles Riley’s influence (if not Riley himself) traveled to Berlin with Jesse Owens. Riley had to read about his pupil’s spectacular Olympic performance in the Cleveland newspaper. Jesse Owens’ victories in Berlin shocked the world: he won four gold medals, establishing four new world records in the process. Moreover, Owens’ performances embarrassed Adolf Hitler who, while at the height of his political power, had to sit stone-faced and watch an “inferior” black American from Cleveland, Ohio completely dominate Germany’s supposedly “superior” Aryan athletes.

When Owens arrived home after the Berlin Olympics, he was a national hero. Endorsement offers came in droves and, for the first time in his life, Jesse Owens had money to spare. To show his appreciation to his coach and “Irish father,” Owens presented Riley with a new Chevrolet car to replace the ageless Model-T. Riley cried with joy. The two of them had come a long way since that day in 1927: Riley had helped rum a scrawny, sickly little boy into the world’s greatest athlete. Jesse Owens himself gave Charles Riley all the credit: “He trained me to become a man as well as an athlete.” In becoming a mentor to Jesse Owens, Charles Riley left an indelible mark on American sports.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March/April 1997 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply