THE invader, the trader, the traveller, the settler, the oppressor, the rebel and the writer have all added colour and culture to the ancient city of Dublin.

Few places have produced so many heavy hitters in the literary field— Swift, Joyce, Shaw, Wilde, Beckett, Behan. Plus the greatest horror-writer of them all, Bram Stoker.

Lesser-known writers too: Dublin man Robert Tressell, born Robert Noonan in 1870, left for England where he wrote The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, exposing the harsh realities of working-class life.

Their ghosts lurk in every corner, and often in the pubs.

The city that produced these writers along with the political thinker Edmund Burke, Dr Barnardo, the artist Francis Bacon, the Duke of Wellington and U2, hasn’t changed that much in character over the years, despite the many superficial changes.

Dublin is in equal measure thoughtful and frivolous, decadent and pious, creative and convivial — and undoubtedly one of the great cities of the world.

Enjoy pints and political chat (image by Gerd Eichmann on Wikimedia fCommons)

Enjoy pints and political chat (image by Gerd Eichmann on Wikimedia fCommons)Stories in every snug and in every sip

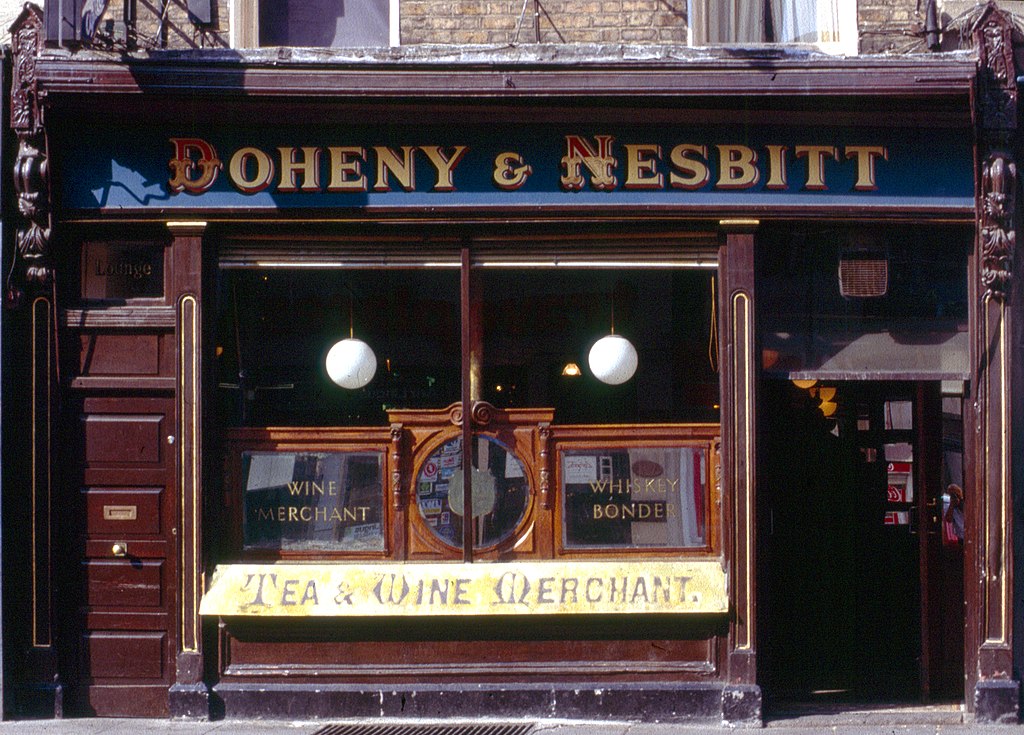

Doheny & Nesbitt on Baggot Street, has been serving the thirsty people of Dublin since the 19th century.

Vintage decor, cosy snugs, and a rich history, it’s popular among politicians, locals, and tourists.

Plus it’s just on the other side of the street from O’Donoghue’s, the cradle of traditional music seisúns which oversaw the birth of The Dubliners.

The Palace on Dublin’s Fleet Street is one of the great bars of the world, in the same company as the Bull and Castle on Lord Edward Street, near Christ Church. Both are almost the embodiment of “Dublin in the rare ould times”.

At the Shelbourne Hotel, waiting staff in black and white livery will sway as they carry silver platters of gleaming black Carlingford and Galway oysters through the famous Horseshoe Bar.

As well as being a five-star slice of studied luxury overlooking St Stephen’s Green, the Shelbourne resounds with echoes from Ireland momentous past.

This is where, you will be told by the barman, two very significant events in Irish history happened: the drawing up of the Irish Constitution and the creating of Black Velvet, the Guinness and champagne cocktail.

Unlike most other pubs in Dublin which have been frequented by battalion of the finest writers in the English, Ryan’s in Parkgate is notable in that Ludwig von Wittgenstein was a local’ The philosopher regularly sat in the pub, doubtless thinking thoughts along the lines of” “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof there must be silence.” Philosophy, eh? Makes you think.

There is music to be found around every corner in Dublin

There is music to be found around every corner in DublinBetween the jigs and reels

Dublin’s place in world literature is well documented. But it is an intensely musical city, famous not just for traditional seisúns, U2 and Fontaines D.C., but also for classical music.

In the 18th century Dublin had so many European classical composers and musicians living there (for many complex reasons) that some musicologists credit the rich embellishments that Irish traditional music displays, is in some part due to this situation.

One of classical music’s great set pieces was first performed in Dublin.

The world premiere of Handel’s Messiah was staged in 1742 in Neale’s Great Musick Hall, Fishamble Street.

Everything from rock to baroque is still available in the capital.

But of course what Dublin is famous for is traditional music.

Concerts, street buskers, workshops, festivals, fleadhs, and not forgetting endless pub sessions, are devoted to one of the finest expressions of folk culture in Europe.

The Cobblestone in Smithfield is basically pints on the table and music in the air. Sessions, gigs, classes, talks, dances — you can expect them all. And a very warm welcome.

Some years ago Armagh traditional music organisation Ceol Camloch held a party in the Cobblestone to launch their traditional music archive.

Some of the finest musicians from Armagh and surrounding areas gathered in the Cobblestone — generations of families playing banjo, accordion, fiddle, pipes were going at it with the afterburners on.

I was at the bar when a young Dutchman happened to arrive. He’d only been in the country some five hours, and had somehow stumbled into the function room at the Cobblestone.

He was amazed that the bar was free — and although this was a private event, none of the Armagh people seemed moved to show him the door.

So he tucked into his Guinness, and indeed some sausage rolls, also provided free.

Unlike most Dutch people this chap’s English was only marginally better than my Dutch, i.e, not very good at all.

I tried to explain that this wasn’t a normal evening in the pub; that it was a private bash, although he was more than welcome to stay.

But by then our young Dutch friend had downed a couple of pints and was entranced by an Armagh dancing master perform the brush dance, even taking to the floor himself before tripping over the brush. He had a ball.

He wanted to leave the Cobblestone, and head in the direction of Temple Bar, probably believing he’d find generations of Dubliners singing traditional songs, feeding him free Guinness and sausage rolls, the works. And maybe he was right.

But some helpful Armagh ladies said no, and persuaded him onto the coach that was taking us back to Camlough. Apparently he stayed two more nights there. Céad míle fáilte, we may assume, was extended to the young gentleman.

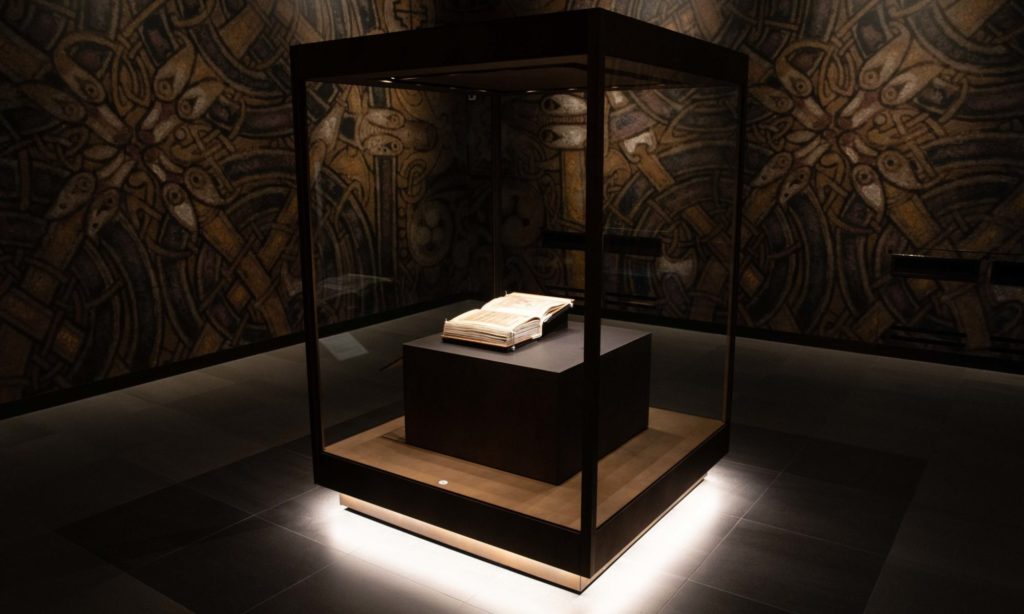

You must pay a visit to the Book of Kells (Pic: Copyright The Board of Trinity College Dublin)

You must pay a visit to the Book of Kells (Pic: Copyright The Board of Trinity College Dublin)Mona Lisa? Meh. Book of Kells? A must-see

I’m ashamed to say I got lost trying to find my way to Trinity College.

Rather than getting out my smartphone, I asked a young businessman (or at least he was wearing as a suit and carrying a briefcase) for directions.

He tutted, and turned from the opposite way he was headed. “Come on,” he said, “I’ll walk you there.”

It was a 15 minute traipse (I was really lost) but here’s the funny thing: the whole way he complained about how unfriendly Dublin is, how nobody has time for anybody else — presumably not grasping the irony of his showing me the way; something unlikely to be repeated in many other European cities.

Safely delivered to my destination, and in thoughtful mood, I went to look for De Buke.

The Book of Kells – also known as the Book of Columba – is an ornately illuminated manuscript (don’t ask them to switch it on, folks!)

Produced by Celtic monks around AD 800, it is quite simply one of the most beautiful man-made creations you’ll ever see.

It’s reckoned today to be one of the most valuable books in the world — when it visited Australia briefly a few years ago, it even had its own black box recorder.

In the unfortunate event of the plane carrying it going down, at least the Book of Kells might be saved.

Written in Latin on the velum of, reputedly, 170 cattle – sadly there’s no vegan version, no vegetarian option as it were — the four Gospels of the Bible are decorated with bling you could see from outer space.

People queue to see the Mona Lisa. They think you can’t visit Paris without seeing the painting. But you can. Really.

However, and it’s a very big however, there’s no way you can miss the Kells masterpiece. Just looking at it draws you into another world, another dimension.

(Sorry about waxing so lyrical there. Maybe I had too many Guinnesses at the Storehouse.)

Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin

Christ Church Cathedral in DublinThe power trio: Silkbeard, Strongbow and Swift

Ireland’s oldest cathedral, Christ Church, was founded sometime after 1028 by King Sitric Silkbeard, the Hiberno-Norse king of Dublin.

It was a Viking wooden affair, so a complete rebuilding was commissioned in 1172 by Norman overlord Strongbow, aided by Archbishop Laurence O’Toole, Dublin’s patron saint — both of whose remains lie in the Cathedral.

A short stroll from Christ Church is St Patrick’s Cathedral.

The patron saint baptised converts to Christianity in the grounds of the cathedral with water from a local well. Since then (5th century) a church has stood on the grounds.

The Normans built a substantial edifice in the 12th century, the core of today’s cathedral. Jonathan Swift, dean here in the 18th century, has a suitably impressive epitaph on his tombstone:

Here is laid the body of Jonathan Swift, Doctor of Divinity,

Dean of this cathedral Church, / Where fierce indignation can no longer

Rend his heart / Go, traveller, and imitate if you can

This earnest and dedicated Champion of Liberty

Near Swift’s tomb is a wooden door through which the Earl of Ormond and the Earl of Kildare shook hands ending a feud in 1492 — said to be the origin of the phrase ‘chancing your arm’.

The Guinness Storehouse in Dublin’s St James’s Gate has been brewing Guinness for 264 years

The Guinness Storehouse in Dublin’s St James’s Gate has been brewing Guinness for 264 yearsStout work at the Storehouse

No trip to Dublin would be complete without a visit to the Guinness Storehouse at St James’s Gate.

Dubs initially turned their noses up at the drink— because of Arthur Guinness’s opposition to the United Irishmen (visceral politics have always been part of Ireland’s story).

But the attractions of the new drink soon overcame political considerations. Up the rebels, down the hatch.

You can see where Sir Arthur’s brewing process began in the former fermentation plant, helpfully remodelled in the shape of a giant pint glass.

The secrets of stout, how roast barley gives Guinness its deep ruby colour, and how a perfect pint is pulled are dealt with in some detail.

The tour ends in the Gravity Bar – a drinking establishment with a 360 degree panoramic view across the city — a brew with a view.

This is the perfect place to contemplate Ireland’s capital, have a few more pints, ponder the meaning of life, have a few more pints, discuss with your friends whether this is the best day you’ve ever had in your life, have another pint.

City of love

“Some who have heard him, say that he speaks with a Dublin accent.”

That was James Joyce referring to the devil – and he could be right.

But there are plenty of people in Dublin who’d keep the devil in his place, not least the battery of saints acknowledged in the city

The St. Patricks weeks festival in mid-March is a knees-up of pagan abandon.

But it’s not all craic & roll. Dublin is home to the world’s third most popular saint after — St Valentine. His Feast Day is another of those calendar markers like December 25 which involves a saint, a bit of food, a scoff of chocolates, some vague traditions and the great organ grinder of commerce.

And yet the remains of St Valentine lie in a modest casket in an unassuming Dublin church, with little in the way of commercialism surrounding it.

Whitefriar Street Church on Aungier Street has no big red neon heart announcing the site of St Valentine’s remains, no interactive digital display welcoming you to some romance heritage centre. Well done to all concerned!

Valentine wasn’t Irish — it’s doubtful if Guinness ever passed his lips. However, his remains were brought to Dublin in 1835 by one Father John Spratt, donated to him by a grateful Pope.

EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum is well worth a visit

EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum is well worth a visitThe Irish Emigration Museum (EPIC)

The Irish Emigration Museum (EPIC), located in Dublin’s Docklands, offers an immersive exploration of Ireland’s emigration story.

Opened in 2016, it highlights the journeys of over 10 million Irish people who left the island.

Through interactive exhibits, visitors discover how Irish emigrants influenced global culture, politics, and science.

The museum covers the Great Famine, conflict, and opportunity, showcasing personal stories alongside broader historical narratives. EPIC emphasizes the enduring impact of the Irish diaspora worldwide.

Named Europe’s Leading Tourist Attraction multiple times, it provides a unique, engaging way to connect with Ireland’s rich heritage and its far-reaching global influence.

This digital museum features 1500 years of Irish history and relives some of the greatest achievements in music, literature, sport, politics, fashion and science.

From The Messiah to mummified Crusaders

OK, Led Zeppelin may have played the very first live version of Stairway to Heaven in the Ulster Hall in Belfast (really), but St Michan’s Church in Dublin 3 has the very organ, built exactly 300 years ago in 1724, on which Handel composed his Messiah.

The church, which was built in 1685-86 on the site of a former Danish chapel, is famous for its collection of mummified bodies stored in the vaults.

The limestone in the ground has kept the air dry and has helped preserve the earthly remains of crusaders, leaders of the 1798 Rebellion, plus the ordinary people of Dublin.

The Ha’penny Bridge over the River Liffey

The Ha’penny Bridge over the River LiffeyThe Liffey

The Ha’penny Bridge — officially the Liffey Bridge — is a pedestrian bridge built in May 1816, making it the oldest pedestrian crossing across the river.

The Liffey flows through the heart of Dublin, shaping the city’s geography and culture.

Rising in the Wicklow Mountains, it travels 125 km before emptying into Dublin Bay.

Its banks have inspired countless poets, including James Joyce and W.B. Yeats, who captured its reflections of Irish life.