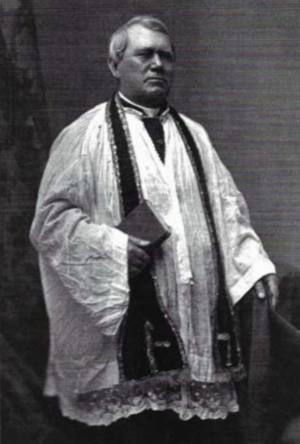

A Shy Priest from Cavan Who Helped Tame a Frontier Town

Imagine him, pale Irish skin against a black robe. On that bright spring morning in 1845 when he first arrived in the little town that was fast-filling a mud shelf overlooking the Missouri River, the Indians – the Shawnee in their calico flocks and turbans, the Sac and Fox with their shaved heads and painted faces – must have viewed Bernard Donnelly with curiosity and amusement.

Freshly ordained, the young priest from Kilnacreva in County Cavan could probably sense even then that this isolated and seemingly godforsaken Town of Kansas would test his stamina and his faith. His friend and mentor, the veteran traveler Father Thomas Burke, had warned him about the ambivalent Indians and the half-wild French Canadians who came and went from the muddy trading center near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers.

“Keep yourself in the friendship of God, Bernard,” Father Burke had counseled, “and like St. Patrick, the very snakes will run away from you. As you are a canny North of Ireland man, take it from me, you’ll give more out here than you’ll ever get.” The older Irishman’s words could hardly have been more prophetic. For 35 years, Father Donnelly would give his heart, his soul, his sweat, his cash and, ultimately, his entire life to the little settlement at the far western edge of Missouri that today we know as Kansas City.

Born of parents who could neither read nor write, Father Donnelly grew up interpreting letters from America. Letters in which emigrant friends of the family boasted of well-paying jobs building the Susquehanna Canal; of huge, wide open spaces; and of home sites out west “just there for the takin’.”

But what the young Irish priest found at the far end of the Missouri River steamboat line was rougher and muddier and lonelier than he ever could have imagined. In his handwritten memoirs, Donnelly recalled that spring day in 1845: “On arriving at the far distant Mission of Westport Landing — now Kansas City — I found a small congregation of Catholics, strangers to me in language, dress and personal appearance. Some of them were fair, some semi-white, some dusky Indians and even some were Negroes, but the majority of them were pale-faced, sickly looking halfbreeds, all — with very few exceptions — a pious, honest and hospitable class of people.”

That first day on the levee, Father Donnelly assisted the circuit-riding bishop of his new mission by administering the sacrament of confirmation in a log cabin. Wearing their vestments and equipped with miter, cope and crosier, the two priests were a matter of great curiosity to the rough-clothed citizens of the Town of Kansas.

“They gazed with childish intensity at the bishop and myself during the ceremonies,” the priest wrote. “They were calm and respectful enough until a serious dispute arose among the crowd of non-Catholics around the door. The matter in discussion being’ `which one of us was the clown?'”

But saving souls was and is serious business, and Father Donnelly would return again and again as part of his pledge to minister to his “parish,” which he likened in size to a “European kingdom.” The young priest was responsible for all the pioneer souls scattered across several thousand square miles, from the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, north to Cameron, east to Boonville and south to the Arkansas border. From 1845 to 1855, he went virtually anywhere there was a pocket of French, German or Irish Catholics in need of sacraments, often traveling more than 30 miles a day on horseback.

His homes were a pair of log cabins, one in Independence and one atop a high bluff above Westport Landing and the Town of Kansas, and, on any given night, the floor of a farmhouse or barn, or the ground beneath a wagon. He preached in English, French and Osage, and it is said that when he heard a response in the soft brogue of Ireland — as he did whenever he visited the James Egan family in the better-established town of Westport — he generally stayed put for an extra day or two.

No starvation, No Misery Here

His diary details near-inhuman conditions — floods, frostbite, ravenous insects, dark, unmarked roads and nights hopelessly lost in the wilderness. Still, Father Donnelly would recall that time in history as “the Golden age of Missouri. The country literally overflowed with milk and honey,” he wrote. “Every table was loaded with luxuries and every meal was a feast. No paupers, no thieves, no swindlers, no burghlars, no police, no taxes worth considering, no houses of ill fame, no divorces, no infidels, no misery, no incindieries, no shiplaisters, no poverty, no starvation, no purchaseable lawmakers, no villains of any kind.”

Sadly, that would change. But to a young man who had grown up with oppression and poverty — and whose countrymen at home were at that moment starving by the millions — the new and tyrant-free land in Missouri must have seemed near in size and bounty to Heaven itself.

In the ensuing years, Father Donnelly not only assimilated into the growing little river town; he became one of its leading citizens, and an architect of its emergence as one of the most important centers of cattle processing, banking, and warehousing west of the Mississippi.

Educated in Dublin as a civil engineer, and having taught school in Philadelphia, Father Donnelly was on a more-than-spiritual mission. In the years before the Civil War, he issued a call to Irish immigrants stuck in the tenements of New York and Boston to come west and help whittle down the river bluffs so the Town of Kansas could grow and, eventually, become a full-fledged city.

When not traveling to remote regions of his extended parish, Father Donnelly made the best of his little cabin atop the river bluffs, in the heart of what is now downtown Kansas City. He survived those early winters thanks to an Irish stonemason named Connor, who built for him a small fireplace and chimney. Father Donnelly chinked cracks, fashioned chairs and walked over the 40-acre wooded site above the confluence of the Kaw and Missouri, studying the jaybirds, coons, squirrels and rattlesnakes. He raised a few pigs and shared his meager bounty with a cat “about the size of a rat but not so fat.”

In the 1840s, the permanent population of the fledgling river town was at best “fluid,” with a couple of hundred teamsters, trappers, traders and fishermen constantly coming and going from a hundred or so cabins and small warehouses located mostly in the East and West Bottoms. Women were few, and genteel conversation something of a rarity. So, when a learned and traveled fellow missionary paid a visit, nearly every word of conversation was joyously recorded in Bernard Donnelly’s diary.

A Wild Indian from Tipperary

A few weeks in front of winter’s wrath, the legendary Jesuit missionary Father Pierre De Smet and his French-Indian interpreter, Gabriel Prudhomme, tied their flat-bottomed skiff to a tree at Westport Landing in November 1847.

After an exhausting journey down the Missouri from the headwaters in what would one day be called “Montana,” De Smet was disappointed to find that he had just missed the last steamboat of the season. It would be a week before a stagecoach could take him home to St. Louis. Tired as he was, he had little choice but to accept the hospitality of the settlement’s greenhorn priest.

Resting in front of the tiny fireplace in Father Donnelly’s rickety log cabin, with winds off the river whistling through the cracks, the great missionary leaned back and told young Donnelly the following tale of adventure, which had happened just the year before, on a journey to the Flathead country, home of what he called the “relentless” Blackfeet Indians.

The Jesuit and his French voyageurs had been traveling for weeks without sign of the fearsome Blackfeet when, one day just after their morning meal, they were surprised by “a cloud of painted, mounted Indians approaching at full gallop.” The little band was helpless and quickly surrounded. The silent, grim-faced Indians motioned for the teamsters and others to begin walking.

Father De Smet was separated from the group and ordered to sit on a buffalo blanket. The Jesuit said he prayed and, in spite of his strength and experience, cried, for he knew his probable fate. Four robust Indians picked up the blanket and carted him away. But something about the eyes and the muscular physique of one of his captors struck the doomed priest as odd.

The Indians marched their prisoners across grass fields for three miles until they came to a village of wigwams. Squaws with their papooses gathered around, the missionary assumed, to “enjoy the savage satisfaction of torture.” Father De Smet prayed faster. In spite of himself, he cried again and offered supplications to God, his Savior. The brawny savage with the twinkling and seemingly bloodthirsty eyes was his only guard. Suddenly, the huge savage stepped toward him. Father closed his eyes in anticipation of the deadly tomahawk blow.

Then the Indian spoke: “Arrah be me soul it’s a big shame to hear a dacent priesht, cryin’ and lamintin’ in that way lyke an ould hag wid de toothake. Shtop now and don’t be after makin’ a Paddy Fitzsymmon’s mother av yerself, just as if the poeleese, bad luck to thim, were after ye.”

The missionary jerked his head up at the sound of the brogue, and opened his eyes. “Who are you?” he asked incredulously. “And shure it’s meself that’s Andy Ryan from Tipperary’s own county, in ould Eyreland, with respect to your rivirince entirely.” “What did you bring us here for?” inquired the priest. “Is it to murder myself and the poor harmless men who are with me?”

“To kill ya do ya means?” asked the Indian, Ryan. “Augh. A hair of yer heads trim painted crathers will not touch — not while Andy Ryan’s here. But shure we expected you last year but you didn’t come so we watched for you this time and gloory be to God, we have ye now and we will give ya something to do, to raise yeer holy hands over us for we want it badly.

“Begorra, yer rivirince,” the Irish Indian continued, “we are as bad as haythens in this hell of a kinthry, beggin’ yer rivirince’s pardon fer cursin’.”

Father De Smet came to discover that the Indian Andy Ryan was wed to a tribal chief’s daughter, and was worded sick that something would happen to his four children — or the other children in the village — before they had a chance to be baptized into the Catholic faith. So that, Father De Smet told Father Donnelly, is what he did for the next few days. He baptized Blackfeet children, sacramentalized Ryan’s marriage to the Indian princess, ate what he suspected was canine stew, and “smoked a peaceful calumet” in the wigwam palace of the tribal chief.

Note: This story is purportedly true — at least it was faithfully transcribed by Father Donnelly himself after his 1847 visit from Father De Smet. There is, of course, an off-chance that as the two men exchanged stories before Father Donnelly’s fireplace, they might also have shared a bit of brandy.

A footnote to Father’s Donnelly’s handwritten account claims that, about 1840, a prosperous immigrant named Ryan, who was living in eastern Missouri, sent money home to Ireland to pay for his “softheaded” brother, Andy Ryan’s, passage to America. Andy, the story goes, fell into bad companionship in Missouri and “in a short time became a Sot, a Rioter and a worthless Loafer.”

After witnessing a band of captured Indians — “in their savage glory of paint and feathers” — parading across the hurricane deck of a steamer docked at the St. Louis levee, Andy apparently got the bug to see the untamed West for himself, and signed up to work with the American Fur Company.

He was sent with a group to the Yellowstone country, where he hunted and trapped furs. At some point, the trappers were attacked by Blackfeet braves and all but Andy were killed. Wounded, the big Irishman was dragged off as a human trophy by the Blackfeet. He eventually grew healthy, and because of his size and strength, found favor with the chief and, eventually, the chief’s daughter. Father Donnelly’s memoirs do not say whatever became of the Blackfeet Indian with the Irish brogue.

Leave a Reply