Families of the victims of the November 1974 IRA Birmingham pub bombings say that British authorities are deliberately obstructing their search for the truth about what happened that night, and denying their rights to accountability.

Between March 1973 and November 1974, the IRA exploded hundreds of bombs across Britain, including several attacks on Birmingham. In 1974, Britain saw an average of one attack — successful or otherwise — every three days.

The security forces were under enormous pressure to find those bombing Britain, and they framed the innocent. Judith Ward, a homeless English woman, was wrongly convicted for the February 1974 bombing of a bus of British soldiers and their families, when 12 people were killed. She was freed by the Court of Appeal in 1992. Five people were killed in the October 1974 Guildford pub bombings, and 11 wrongful convictions followed. Their convictions were quashed between 1989 and 1991.

On 21 November 1974, 21 people were killed and 220 others injured when two bombs destroyed the Mulberry Bush and Tavern in the Town pubs in Birmingham city center. Six Irishmen – Hugh Callaghan, Patrick Joseph Hill, Gerard Hunter, Richard McIlkenny, William Power and John Walker – were abused and tortured by police after their arrest, and wrongly convicted for the bombings. Some were forced into signing false confessions, and flawed forensic evidence was used against them.

The Birmingham Six were finally freed in 1991 when their convictions were overturned. They had spent 17 years in prison for crimes they didn’t commit.

As now, Birmingham in 1974 had a large Irish community. Many of the casualties of the pub bombings had Irish parents. Two Birmingham brothers – 22 year-old Desmond and 23 year-old Eugene Reilly – whose parents were from Donegal, were killed in the explosions. Their father John was called by police to a mortuary to identify the body of one of his sons. The Irish Post newspaper reported at the time that “He believed the body would be that of Eugene and that his other son Desmond was 200 miles away in Durham. But the two brothers had been having a reunion drink in the Tavern in the Town [pub] when the bomb exploded and a heartbroken John had to identify the first body as that of Desmond. He was called again to the mortuary by police and found the body of Eugene.”

An estimated 35 of the injured had Irish parents, including 20 year-old junior solicitor Peter Long, whose father was from Cork; Bernadette O’Connor, aged 17, whose parents were from Athlone and Kerry, and 17 year-old Yvonne Donnelly, whose parents were from Kildare and Laois.

After the bombs, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson made a plea for no acts of retaliation against Irish people or people of Irish descent, but within hours of the Birmingham pub explosions bombs were thrown into an Irish-run Prince of Wales pub in Ealing’s Boston Road, an Irish tobacconist’s in Streatham, south London, and an Irish pub in Kingstanding in Birmingham.

The Irish Community Centre at Digbeth in central Birmingham was petrol bombed, and St Gerard’s Catholic School in Castle Vale to the north of the city was hit by an arson attack. Workers at Liverpool and Manchester airports refused to handle flights bound for Belfast or Dublin.

Historian C. Desmond Greaves noted “The disastrous bomb outrage in Birmingham did the Irish movement in Britain more harm than a regiment of cavalry.”

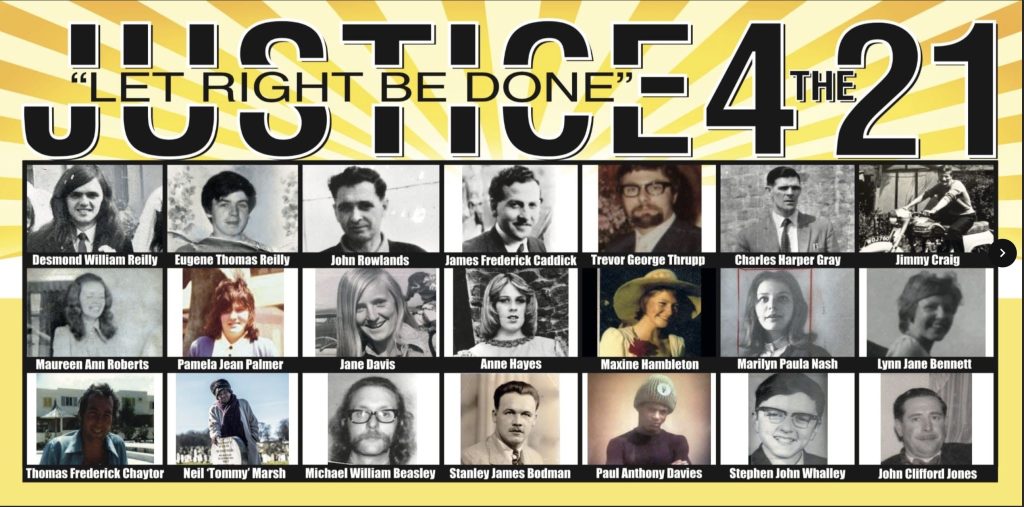

Following the 1991 release of the six wrongly convicted men, survivors and bereaved families assumed the police would reopen the investigation into who been responsible for the bombs. But nothing happened. Around 15 years ago Julie Hambleton joined her brother Brian in campaigning for the truth about what happened to their sister Maxine, who was 18 years old when she was killed in the bombings.

“I started wondering why there was no public inquiry into the biggest mass murder of the Twentieth Century in Britain,” she said. “So in 2009 I wrote to the Chief Constable of the West Midlands Police to ask what he was doing.”

It was, she says, the beginning of a long and painful realisation that the families were being fobbed off, obstructed and underestimated by the British establishment. “It took the Chief Constable five years to respond to the letter,” she said. “They thought if they ignored us we’d go away. They were wrong.”

The families of the victims began to find each other and joined together in a Justice for the 21 campaign. The families applied for and obtained the resumption of the inquest which had stopped because of the conviction of the Birmingham Six in 1975. But they had to fund a legal action to challenge restrictions placed by the coroner on that inquest investigation, a challenge which was successful in the High Court but which was overturned by the Court of Appeal.

“The families got no legal aid. We’ve been denied it 14 times.” said Hambleton. “We had to raise the costs ourselves – fundraising concerts, donations from groups of football supporters, wherever we could. People have been amazing in helping us, but they shouldn’t have to.”

The inquest was finally reopened, but with such strict limits that the families dismissed it as a farce. Hambleton said: “The rules were that the issue of [British State] informants in the IRA couldn’t be discussed, and nor could the issue of who had done the bombings.”

A witness whose identity was protected at the inquest – a convicted IRA bomber known as Witness O – testified that the IRA had told him he could reveal the names of four alleged perpetrators: Mick Murray, James Francis Gavin, Seamus McLoughlin and Michael Hayes. Another man, Michael Patrick Reilly, was separately named in a 2018 TV documentary and it was suggested he might have been one of those who planted the bombs.

Maxine Hambleton’s mother, Margaret Smith, has taken a civil court case against Reilly, and is also suing Sir David Thompson, chief constable of West Midlands Police, claiming the force’s investigation was conducted negligently.

Julie Hambleton says the British authorities continue to cover up the truth, that officials knew the bombings would happen but deliberately let them go ahead, for three possible reasons. “First, although a Prevention of Terrorism Act giving police greater powers had been discussed, it hadn’t become law. It was passed within a week after the bombings. Second, Birmingham was a lucrative place for IRA fundraising in Irish pubs and clubs. The horror of the bombings ended that; and third, the British were and are protecting informants they had in the IRA.”

Some of the families’ frustration is also directed at Chris Mullin, the journalist (and former Member of Parliament) whose research did much to expose the false convictions of the Birmingham Six. While the families applaud that work, they are angry that he refuses to name those he says are guilty of the bombings, citing promises to protect his sources.

Lawyer Christopher Stanley of KRW solicitors represents some of the families. “The way the families see it, this is an unsolved murder case with no justice for the victims.” he said. “They’ve been left in limbo because there has been no active investigation since 1991.”

Last year, Britain’s Crown Prosecution Service said there was insufficient evidence to bring charges following a re-investigation into the deaths of the 21 people killed in the bombings.

But the campaign for a full public independent inquiry continues. “I’m not interested in an apology or compensation,” said Hambleton. “This isn’t about money, it’s about truth and accountability. The authorities are delaying and denying, and dismissing us, waiting for us all to drop dead. If they’ve got nothing to hide why are they trying to block us at every turn – what are they scared of the public finding out?”

Follow Brian on Twitter @dooley_dooley

Leave a Reply