180 years after his birth on June 28, 1844, the lessons of legendary Irish rebel, patriot, poet, and activist John Boyle O’Reilly deserve to be remembered and cherished.

In today’s society of discontent and distrust mingled with guarded hope and optimism, O’Reilly would be hailed simultaneously as a disruptor of the status quo, a man unafraid to speak truth to power, a uniter not a divider, a change-maker. He would be recognized as both an American patriot and an Irish patriot in equal measure. He would be valued for his friendship and loyalty, for his unfettered curiosity and sense of adventure, and for his sense of purpose to something bigger than himself, namely, the principles of democracy, liberty and freedom.

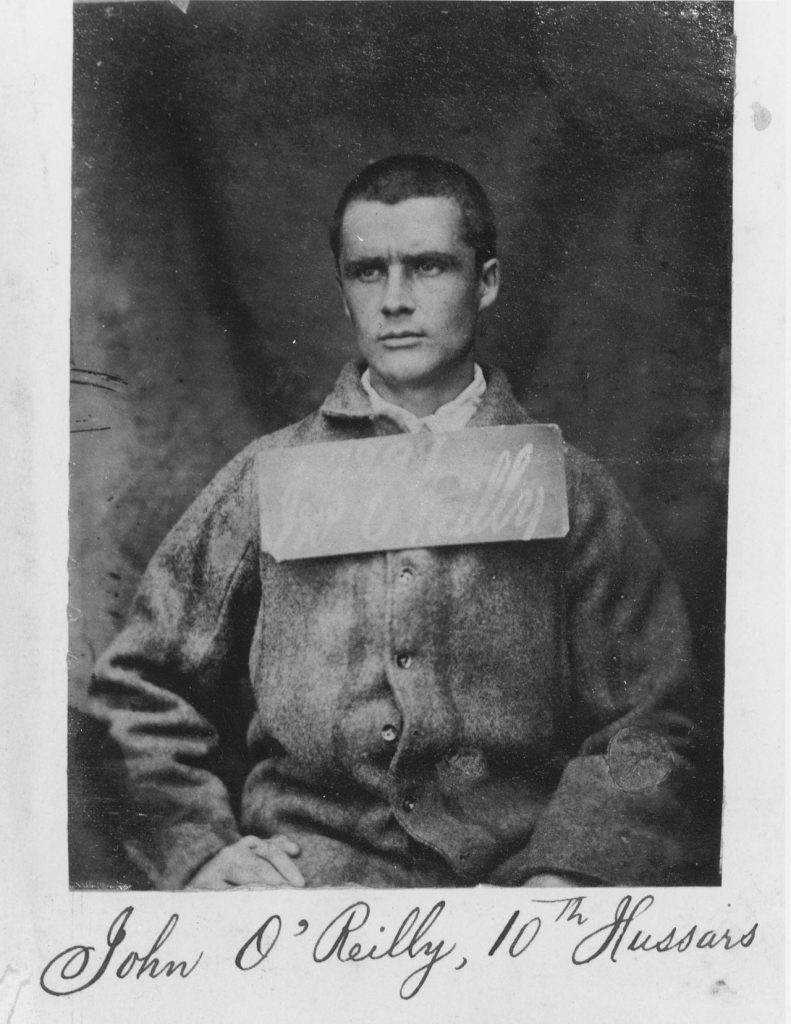

As a young man living in post-famine Ireland, O’Reilly (1844-1890) first gained notoriety as an escaped convict from an atrocious and imperialist brand of British justice. Sentenced at age 23 to life imprisonment for sedition against the Crown, he and his fellow Irish rebels were shipped to a penal colony on the outer edge of western Australia, a part of the world known as No Man’s Land.

Within months, O’Reilly made a daring escape, scrambling at night through the desert and the bush before rowing out to sea on a boat and jumping aboard the New Bedford whaling ship Gazelle that carried him across the high seas. The whaler was frantically pursued by British ships hoping to capture O’Reilly and prevent him from becoming another hero in the Irish cause.

Arriving in America in 1869, O’Reilly spent a brief time in Philadelphia and New York City before visiting Boston in January 1870, where he quickly decided to settle. He spent the final two decades of his brief but shining life here, where his legend truly took shape. O’Reilly’s early infamy quickly turned to fame, for it was as a writer, orator and unabashed defender of the downtrodden that his lasting contribution to society became apparent.

A printer’s apprentice as a boy and a journalist briefly by trade, O’Reilly used his language and literary skills to secure a job at Patrick Donahoe’s Boston Pilot newspaper, the mouthpiece for Boston’s Irish Catholic community with a national readership. His first assignment was covering the failed Fenian invasion into Canada in April 1870, and before long he was promoted to editor and eventually became co-publisher of the newspaper.

The Pilot gave O’Reilly a perfect platform to pursue his most cherished cause: Ireland’s freedom from British rule. This advocacy caused the British to double down on their acrimony toward him; they refused to let O’Reilly return to Ireland for his father’s funeral in 1871 and vowed to arrest him if he came to Canada for a speaking engagement.

But he persisted, advocating for Ireland’s Land League and Home Rule movements, and welcoming Michael Davitt, Charles Stewart Parnell and numerous Irish leaders to Boston. In 1876 O’Reilly and John Devoy hatched a daring plan to rescue six of the remaining Irish prisoners still in Freemantle. They employed another New Bedford whaling ship, the Catalpa, to pull off one of the great escapes of the 19th century.

Perhaps O’Reilly’s most enduring contribution was his tireless efforts to reconcile the city’s fractured racial and ethnic factions. He immediately befriended the Yankee establishment, who admired his poetry and intellect, even while he firmly admonished them for their own prejudices. He defended African Americans seeking post-Civil War equality and Indigenous tribes being slaughtered out West. He was sympathetic to new immigrants such as Jews and Chinese, insisting that they deserved the same privileges as Americans.

O’Reilly’s active alliance and friendship with local Black leaders such as Frederick Douglas and Lewis B. Hayden put into motion a continuous tradition of respect, common purpose and mutual support between Boston’s Irish and Black communities that remains unbroken today, despite challenges and setbacks along the way.

In his famous poem about Crispus Attucks, a sailor of mixed African and Indigenous ancestry and the first victim of the Boston Massacre, O’Reilly posed the question, ‘Where shall we seek for a hero, and where shall we find a story?’ before praising Attucks and the other American patriots who stood up to British tyranny and created the United States of America.

O’Reilly’s power as an orator was legendary. He was chosen to recite original poems at the Boston Massacre Monument dedication on Boston Common, the Pilgrim Fathers Monument dedication in Plymouth, and Memorial Day and Veterans Day services in Everett. He spoke with passion and conviction at multiple gatherings, from the Thomas Moore centennial banquet at the Parker House and the gravesite of Fenian Thomas J. Kelly at Mt. Hope Cemetery to the Massachusetts Colored League convention at Faneuil Hall.

Leading American writers of the day such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman openly admired O’Reilly, and so did Irish writers Oscar Wilde and W.B. Yeats. In fact, Yeats credited O’Reilly as being among the first editors to publish his early poems in the 1880s.

In addition to his intellectual interests, O’Reilly was a celebrated amateur sportsman who believed in the physical, mental and spiritual benefits of sports. His 1888 book, Ethics of Boxing and Manly Sports, included a treatise on pugilism — he was friends with heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan — and sketches of O’Reilly’s canoe trips throughout New England and Pennsylvania. An essay in the book, “How to Grow Strong by Exercise, Training, Diet and Sleep,” was described by one newspaper as “probably the most complete study of this important subject ever made in this country.”

O’Reilly was an original founder of the now-famous Boston Athletic Association, founded in 1887. The BAA put together the American team for the first modern U.S. Olympic Games in 1896, and the following year, created the Boston Marathon, which the BAA still runs today.

He was affectionately called Boyle by his many friends and admirers and had a rich and fulfilling family life with his wife and four daughters.

Looking through today’s lens of social progress, O’Reilly had one glaring blind spot: he was adamantly against the women’s suffrage movement. He wrote in an 1885 editorial, “Women ought to be fully guarded by law in all rights of property, labor, profession, but roughly stated, the voting population ought to represent the fighting population.”

Had he lived beyond his 46 years, I like to believe O’Reilly would have tempered his views and gotten on the right side of history. His wife Murphy was a talented writer whom he met at the Boston Pilot, and he encouraged numerous young women writers such as Katharine Conway, Louise Imogen Guiney, Fanny Parnell and Minnie Gilmore. After his death, three of his four daughters — Mary, Elizabeth and Agnes, went on to become trail-blazing women in the spirit of their cherished father.

As activists, educators and writers, the O’Reilly sisters collectively exposed unfair labor laws against women and children, started experimental schools, covered World War I as reporters from the front lines, lectured widely and published several books, all the while confronting hypocrisy and inequality wherever they found it. They would have surely made their parents proud.

Nearly two centuries after his birth and 134 years after his death, the answer to John Boyle O’Reilly’s poetic musing, ‘Where shall we seek a hero . . .’ may well be O’Reilly himself.

The O’Reilly Women in Massachusetts

For a man whose life was filled with adventure and daring, who loved the great outdoors and sports, especially boxing and kayaking, John Boyle O’Reilly’s greatest joy in life was actually in the comfort of home with his wife and four daughters.

He met his wife Mary Murphy of Charlestown at the Boston Pilot newspaper, shortly after he began working there in 1870. Mary was already a talented writer who published stories in local magazines, using the pen name Agnes Smiley in honor of her grandmother. Mary launched a popular Pilot column for boys and girls called ‘Little Ants,’ creating a wonderful archive of children’s literature for young readers.

John and Mary married on August 15, 1872 at St Mary’s Church in Charlestown, just around the corner from 34 Winthrop Street where the family settled; John was 28 and Mary was 20. Within a year, their first daughter Mary Boyle was born on May 18, 1873, followed by Elizabeth Boyle on July 25, 1874, Agnes Smiley on May 19, 1877 and Blanid Boyle on June 18,1880. These women deeply inspired O’Reilly’s writing for the final 18 years of his life. He dedicated his book, Songs, Legends, and Ballads to his wife, writing, “Her rare and loving judgment has been a standard I have tried to reach.” His last volume of poems, In Bohemia, was dedicated, “To My Four Little Daughters.”

After John’s sudden death from an accidental overdose of medication in 1890, Mary and their four daughters, who ranged in age from 10 to 17 years old, became devoted to his memory and legacy. At the unveiling of Daniel French’s O’Reilly Memorial in 1896, newspapers reported that “Mary, the poet’s widow, came to the stage with her four daughters. They sat as a group on stage….Each of his daughters carried a bouquet of roses and Miss Blanid unveiled the memorial.”

Their mother Mary’s sudden death from pneumonia in December 1897 sent the daughters fully onto their own paths in life, and not surprisingly, they followed in the footsteps of their parents as writers and social activists.

Mary Boyle O’Reilly (1873-1939), nicknamed Molly, wrote creative stories under her mother’s pen name, Agnes Smiley, before becoming a fierce social activist for women and children. She established Boston’s Guild of St. Elizabeth Children’s Home and supported various social service causes. In 1910 she disguised herself as a mill worker to expose child labor abuses in New Hampshire, which led her to a brilliant career in journalism.

In 1914, Mary began reporting for Newspaper Enterprise Associates of America, a syndicate of 200 newspapers. At the onset of World War I, she entered Belgium disguised as a peasant and reported extensively from the front lines, writing, “If half the world has gone mad, it is for the women to see that something like common sense comes back to the world.”

Later in life, Mary built a small stone bungalow in Auburndale near Boston as a tribute to her father, according to her Collected Papers at John J. Burns Library at Boston College. She died at age 66 of a heart attack.

Elizabeth Boyle O’Reilly (1874-1921), nicknamed Eliza or Bessie, also began as a poet, publishing a selection of verse in 1903 titled My Candle and Other Poems. After traveling to Europe with Agnes and Blanid in 1904, Eliza remained there, conducting extensive research for two massive cultural travel books. Heroes of Spain, published in 1910, was praised for its “sympathetic estimate of the Iberian peninsula and its people, drawing chiefly from the less traveled region of the Peninsula where the dominant characteristics of old Spain are still said to flourish. ”Her masterpiece was the 600-page tome, How France Built Her Cathedrals: A Study in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, published in 1921. The New York Herald called Eliza “noble” for undertaking “this elaborate study of the French cathedrals, which is at once history, description and interpretation.”

Agnes Smiley O’Reilly (1877-1955) was interested early on in education and was a substitute teacher in Charlestown after college. On June 28, 1905, the day of her father’s birth, Agnes married philosopher William Earnest Hocking, professor at Harvard College and Yale University. Her request to be married by a Catholic priest was denied by the Archdiocese when she refused to sign a paper promising to raise her children Catholic.

In 1915, the couple launched The Cooperative Open Air School for children on their back porch in Cambridge, a progressive, non-traditional place of learning. It was renamed Shady Hill School in 1925 and still flourishes today. Belgium writer May Sarton, a pupil there, wrote later, “There is no doubt that my creative mind stemmed in those early years from the genius of Agnes Hocking, the schools’ founder and moving spirit.”

Blanid Boyle O’Reilly (1881-1918) the youngest daughter, was named for a mythical Irish character in a book by close family friend Dr. Robert D. Joyce. John wrote a poem entitled “To My Little Blanid,” describing her lovingly as “my little daughter with eyes of blue” who responded to every fairy tale he read her with the question, “Oh, is it true?”

Not much has been written about Blanid, and there is no evidence she took up writing or social activism. After their trip to Europe in 1904, Blanid returned to attend the wedding of her sister Agnes. Five years later, the 1910 US Census reported her as being an inmate at the Worcester State Hospital for mental patients. In 1918, she died in Maryland at age 38.

In later years, mental illness cast a dark and mysterious shadow upon the lives of the O’Reilly sisters. When Elizabeth returned from Europe in April, 1918 to complete her book on French cathedrals, her sisters Mary and Agnes had her committed to an insane asylum in Massachusetts, for “talking in an irrational manner.” She escaped after 18 months and fled to New York, where her sisters again tried to have her admitted to Bellevue Hospital psychopathic ward. Eliza was placed in protective custody with her lawyer while Judge Robert F. Wagner weighed the evidence, eventually ruling that she was indeed sane and free to go. Her book was published a year later by Harper & Brothers in June 1921, and she died of cancer on September 11, 1922 in New York City.

While this sibling dispute was a tragically sad coda to Elizabeth’s life especially, it is indisputable that the O’Reilly women were extraordinary in their own right, much like their parents.

For more information about John Boyle O’Reilly, follow Michael Quinlin’s blog, Irish Boston History and Heritage.

Leave a Reply