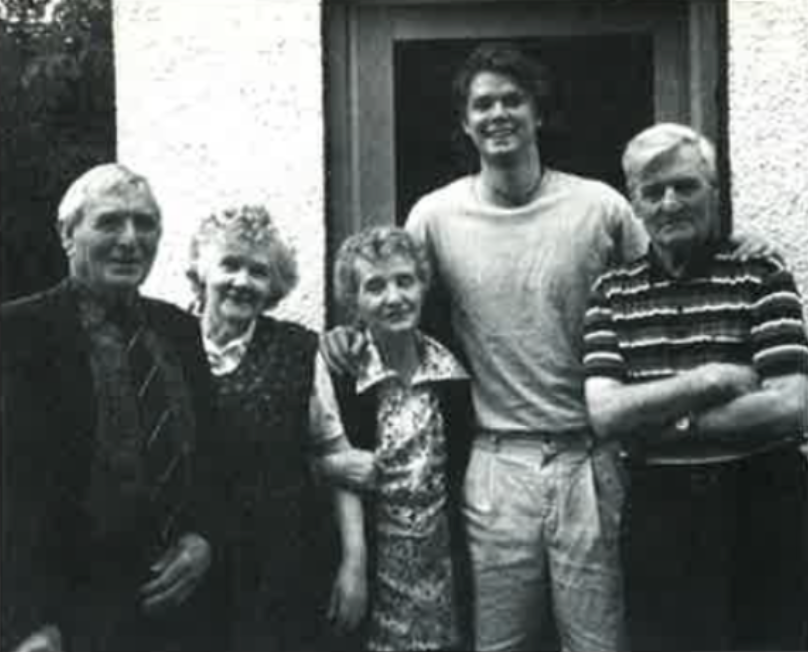

It had been 20 years since my first and only visit to Ireland — a month-long stay on my grandparents’ farm in County Mayo with my mother, father, six siblings, two cousins, and a lot of cows.

I was only six at the time, and in my mind Ireland remained a place where I could of play among haystacks twice my size, choose a pretty calf to be my own, buy Cadbury chocolate bars in the town of Westport, and watch for the leprechauns who supposedly lived on Fergus land.

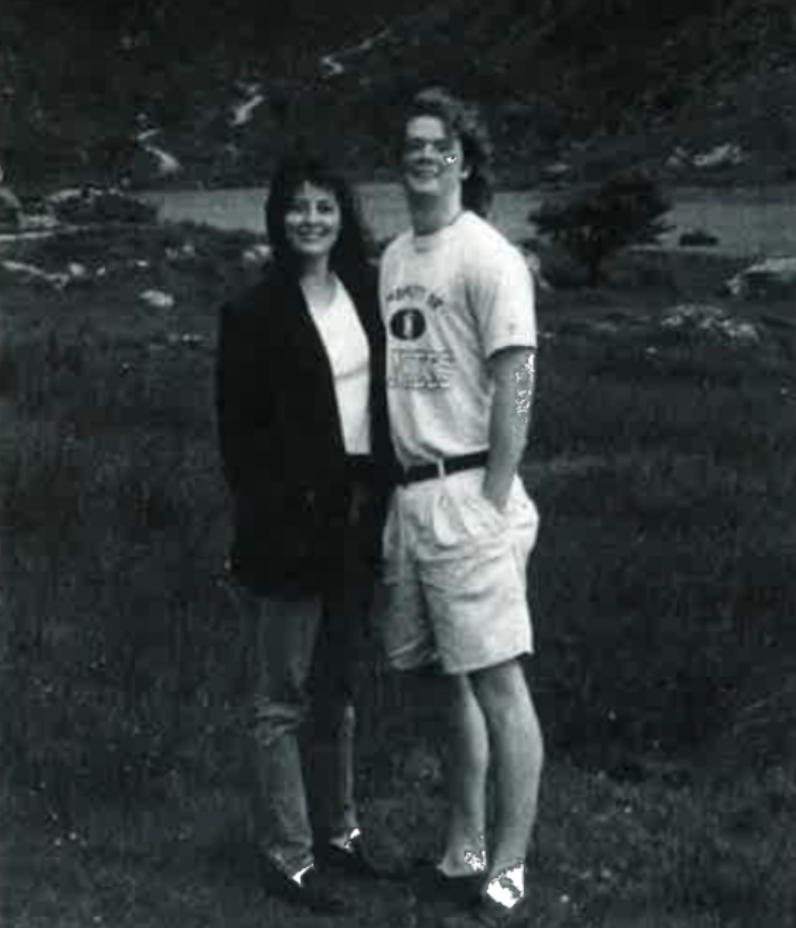

My grandparents are no longer alive, but my images of them and of the country have stayed with me. Twenty years was long enough. I wanted to see the old farm again, to visit the places my father talks about from his childhood — Clew Bay, Croagh Patrick, Louisburgh, and Knocknagree, the tiny town in the south where he met my mother. So last summer, my 24-year-old brother, Patrick, and I left New York City with an address book filled with the numbers of our many Irish relatives — people I hadn’t seen since 1975 — to reacquaint ourselves with them and with the land of our ancestry. I think my parents were more excited than we were, if that’s possible.

My mother’s cousin Eileen Walsh had invited us to stay on her 100-acre sheep farm on the outskirts of Cork. It was a three-hour drive from Dublin airport, and on the way Patrick and I agreed that the farm would be a perfect reintroduction to Ireland. As soon as we arrived, Eileen fixed sandwiches and tea, and we spent the evening catching up on Fergus and Walsh family news. (Eileen’s husband, Eamon, promised to show us the sheep first thing next morning.) Inevitably, photo albums appeared and we pored over black-and-white pictures. Other relatives dropped by, including Jamie and Davy Twomey. They showed us old newspaper clippings about their father, a local politician who may or may not have known Michael Collins (1890-1922), the great nationalist leader from Cork.

Eamon jokingly chided us when we rolled out of bed at 10 a.m. the next morning; he’d been up since dawn. Though we weren’t yet on farm time, our interest in the sheep was genuine. In an enormous field bordered by a split-rail fence, we surveyed his flock of about 250 animals. I was sorry to have missed the lambing season in February, when the sickly newborns are brought into the house to warm by the fire. That image made me wonder if Eamon ever got attached to them. “Well,” he said with a laugh, “it wouldn’t be a very good idea.”

In the afternoon we set off for Cobh, a seaside town 15 miles southeast of Cork. It was from here that steamer ships embarked on countless transatlantic journeys, separating thousands of people from their families — usually forever. The $4 million Cobh Heritage Center, completed in 1993, documents the sad saga of Irish emigration that essentially began with the Great Famine of 1845 and continued in waves until boat service was halted almost a century later. I felt as if I already knew the grim faces shown in the photographs, because one of those emigrants was my grandmother Hannah Twomey. In 1926, at are age of 17, she left Knocknagree to start a new life in America. She landed on Ellis Island, settled in New York, and eventually married a fellow Cork native with whom she had two daughters — one of them my mother, Bridie.

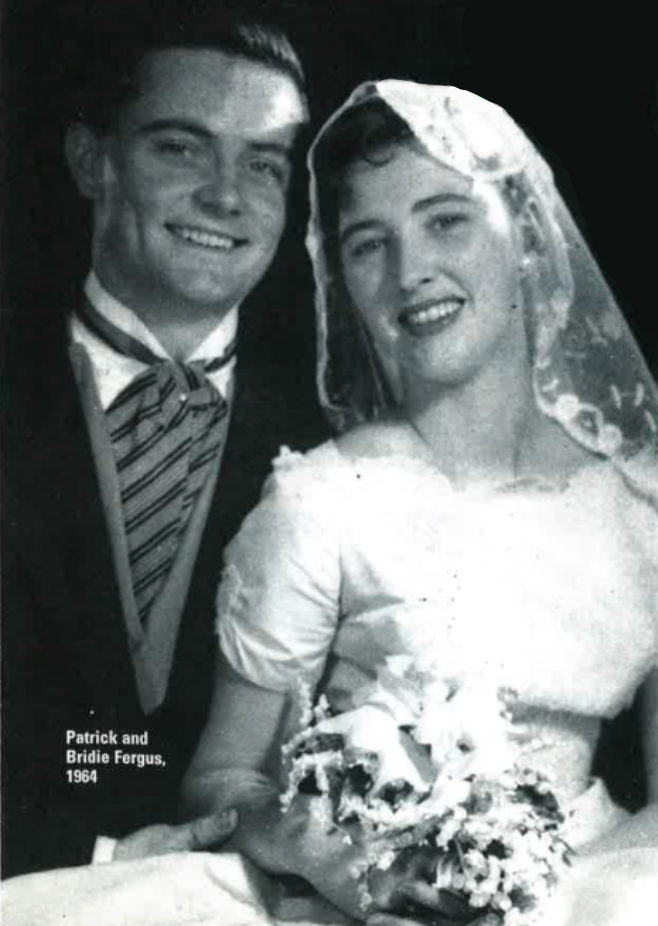

Back at the Walshes’ farm, Patrick and I had a late lunch (lamb chops, what else?), then set off on the 20-minute drive to Knocknagree. It seems I’ve been hearing that name my whole life; although it’s only an ordinary farming village, Knocknagree is where my parents met. As the story goes (and it gets more dramatic each time it’s told), in the summer of 1960, my 21-year-old mother planned to visit her aunt Mary, who lived on the town’s main square. Patrick Fergus, also 21, was a garda (policeman) with the good fortune to be stationed in Knocknagree: beyond the occasional cow theft or sports-related donnybrook, there wasn’t much in the way of crime.

Word spread quickly of the arrival of Mary Twomey’s niece from America. Aunt Mary told my mother all about the handsome garda from Co. Mayo, but Bridie wasn’t interested; she had a fiancé in New York. A few days later, as she rode her bicycle past the station house, he caught her eye and winked. Intrigued, Bridie wondered if this might he the fellow her aunt had mentioned. The next morning my father heard a knock at his door. A boy he’d never seen before said, “I was told to tell ya the Yank’s by the river.” My father guessed that his friends, who knew he wanted to meet the “Yank,” had put the boy up to it. Grabbing his bathing suit, he hurried to the swimming hole on the Blackwater river, where he and Bridie were finally introduced. For the rest of the summer they took walks together, went to dances, and kissed by the fireplace in Mary’s living room. Knocknagree, so vivid in my parents’ stories, seemed to me like an abandoned stage set. Mary’s house was sold after her death a few years ago, and the old police station is now a grocery store. In the small graveyard at the edge of town, we found several Twomeys, one born as early as 1762.

The next morning Patrick and I were on the road to Killarney in County Kerry while the rain came down heavily. The weather matched my somber mood. As I listened to Sinéad O’Connor’s haunting rendition of “The Foggy Dew,” I thought about something Jamie Twomey had said. He’d talked about the necessity of leaving Ireland to work in places such as America or England (where he’d spent most of his life) because of the scarcity of jobs. But he also said that you always come home. And here I was, in a sense, coming home. Though I was in the middle of a “moment,” Patrick started laughing hysterically. “If you’re like this now, you’ll be a wreck when we get to Mayo!” Around Killarney lies some of the most awesome scenery in all of Ireland. The Gap of Dunloe, accessible only by foot or pony cart (which we opted for), is as dramatic as it gets — broad rocky hills fronted by perfectly round lakes where puffs of mist rise. The lookout point at Aghadoe has stunning vistas of Macgillycuddy’s Reeks, Ireland’s tallest range. The long drive to Clifden, where we’d meet our English cousins Robert and Fergus Horkan, gave us a chance to see more of the countryside, including the famous Cliffs of Moher, where formidable 700-foot limestone slabs jut into the Atlantic.

We joined our cousins and about 40 of their relatives at the Alcock &Brown hotel in Clifden, capital of the Connemara region. They had all just arrived from London for their 15th annual family reunion. The “Horkan Connection” is planned so the group can spend time together in Ireland’s beautiful countryside. Rugged Connemara is the most romantic and unspoiled part of the country. Irish writers have often expounded on its lonely bog-filled landscape, but I’ll always associate it with the rosary beads my grandmother gave me, made from the greenish-black local marble.

Of all the events that take place during a Horkan Connection — music, dancing, card games, soccer — the highlight is always the treasure hunt. Six carloads set out along the eight-mile Sky Road scenic loop, searching for, say, the number of windows in an abandoned church, or haystacks in a certain field. At every turn we saw vignettes of traditional Irish life — a fisherman in an old currach casting his net, an aproned woman working in the yard of her thatched cottage, or a group of red-cheeked kids pausing in their games for a quick wave.

Our days in Connemara were long and relaxed. The biggest decision was whether to go for a swim off a deserted stretch of beach in water as warm and blue as the Caribbean -or just to while away the afternoon at an outdoor café over plates of oysters and pints of Guinness. Nights were filled with music, traditional Irish sing-alongs called seisiúns where everyone gets a turn in the spotlight. Kevin and Dermot, two of Rob’s cousins and fellow sports fans, spent hours discussing the state of Irish soccer with Patrick. It was great craíc (good fun), as the Horkan boys would say.

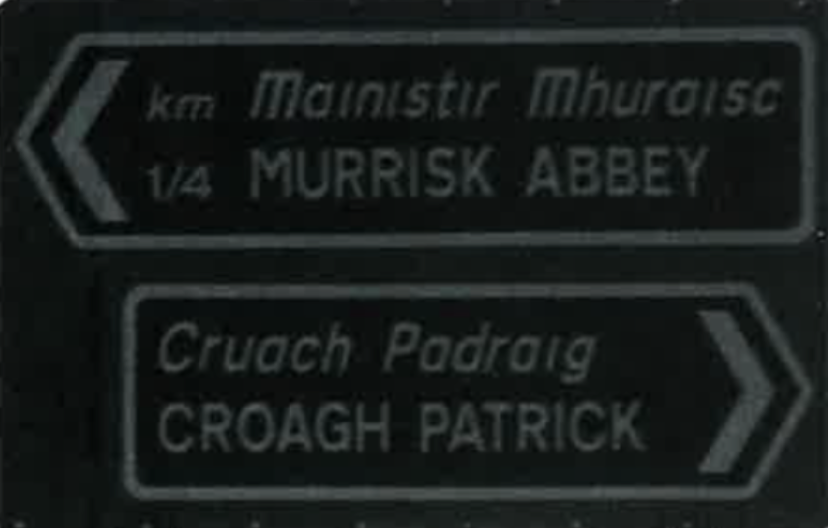

In the town of Westport, about an hour’s drive from Clifden, Patrick and I roamed with our cousins around Bridge Street, the main thoroughfare. Being back in Westport was special for me; this was a place I remembered from that first visit. We checked out the craft shops and art galleries, and looked for the spot where we’d taken pictures as kids, beside the canal that runs through the center of town. Robert and Fergus had spent many summers in the area, so they were our guides. We drove along Clew Bay, said to have 365 islands, one for each day of the year, and stopped for a picture outside Peggy Staunton’s Pub in Lecanvey. Years ago, my grandfather would tall politics and play cards with friends in Staunton’s back room. Now the room has a jukebox and pool table, but the amazing view of 2,510-foot Croagh Patrick, the famous pilgrimage site, hasn’t changed.

When we finally reached the small family farm in the village of Mullagh, it looked nothing like what I recalled. The trees and hedges were overgrown; the green fields, once lined with haystacks, now overflowed with weeds. My uncle Sean, who now owns the farm, travels frequently on business, and the land has suffered from years of neglect. The caretaker wasn’t expecting us, so there was no one to greet us. As I peered into the windows of the house, I almost felt like an intruder. Then on the kitchen mantel I saw a photograph of my two sisters and me. Just beyond the house. Robert pointed out the cherry trees we used to climb, and the old red barn that was our hiding place. I remembered all the hours we spent in those fields, playing with our cousins. We’d try to teach them American games, and my father explained hurling to us. He swore that on certain nights the leprechauns would play a hurling match — a Celtic version of Field of Dreams. I couldn’t imagine a more serene place, right in the shadow of Croagh Patrick. As the eldest son, my father was entitled to the land but he’d known early on that the life of a farmer was not for him. While he was hesitant to leave his family and his country to come to America, he had always dreamed of living in a large metropolis such as New York. Robert and I were heartbroken to think how the land would look in another ten years. As the eventual owners, we made a pact that one day we’d return the fields to the vibrant shades of green they once were.

I missed my father at the farm, but I missed him even more at nearby Murrisk Abbey. This Augustinian monastery is listed in guidebooks because of its 16th-century ruins and graveyard. But for the four of us it was especially significant: our grandparents Thomas and Rose Fergus are buried there. The sun beat down as we stood beside their joint headstone, and for a long time we gazed into Clew Bay without saying a word.

We lunched in Louisburgh, the closest town to Mullagh. In my dad’s time, it was the place to stock up on candy and books from the library. These days there’s an excellent museum dedicated to the 16th-century pirate queen Granuaile (also called Grace O’Malley), who from her castle on Clare Island ruled the western seas of Ireland, hijacking ships and smuggling goods. Years ago my father had given me a book about this infamous woman, and I’d always wanted to see the places it mentioned. To this day, Dad still tells tales about Granuaile and the legendary Cuchulainn, the most feared of all the mighty Celtic warriors.

That evening the four of us met up with Kevin and Dermot at Matt Molloy’s, a busy pub in Westport owned by a member of the Irish band the Chieftains. We settled at a large table to catch a bit of the impromptu seisiún. The musicians played the traditional instruments — tin whistle, fiddle, flute, uileann pipes, and bodhrán — and we sang along, silently lamenting that our trip was coming to an end. My brother and I were both overwhelmed by the reception we’d received from the Walshes, the Twomeys, the Horkans — and all the other Irish people we met. In fact, Patrick and I have even planned our own reunion with our cousins: ten years from now, when we have kids, we’ll all meet at the farm in Mullagh. It will be great craíc indeed.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January/February 1997 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply