Six years have passed since Joe Doherty was deported from the U.S. in 1992 back to prison in Northern Ireland. Brian Rohan talks to Doherty about life behind bars and his thoughts on the Good Friday Agreement.

In a place like Her Majesty’s Prison, The Maze, even the tiniest of details can hold you up.

By ten o’clock on the morning of May 21, I had navigated a series of iron gates and a metal detector, walked down halls of barbed wire and steel, through a two-guard search party within a closet-sized room. At the sign-in desk, I stood — delayed — before a thick Plexiglas window. Behind me, a throng of wives, girlfriends and colicky infants grew larger, as a young, slick-haired guard considered my request for a visit.

The problem, it seems, is a middle initial.

“You want Joseph T. Doherty or Joseph P. Doherty?” the guard asks.

I rifle through my folder of yellowed news clippings: none of them list my prisoner’s middle name. Nor does a listing in my pocket address book. I’m seconds away from telling the guard, “You know — Joe Doherty the famous IRA man,” but I am interrupted by the woman with two screaming children behind me — the woman with green loyalist tattoos inked down her forearm.

“What?” she says, tapping the Plexiglas. “D’ya not even know who you’ve come ta visit?”

Seeing the commotion, an older guard walks up from the back. He speaks into an opening in the Plexiglas.

“Joseph J. Doherty is just Joseph J. Doherty,” he explains. “Joseph P. Doherty — he’s the Yank.”

Six years have passed since Joe Doherty last set foot in America, yet inside the Maze, the Belfast native is still known as “The Yank.”

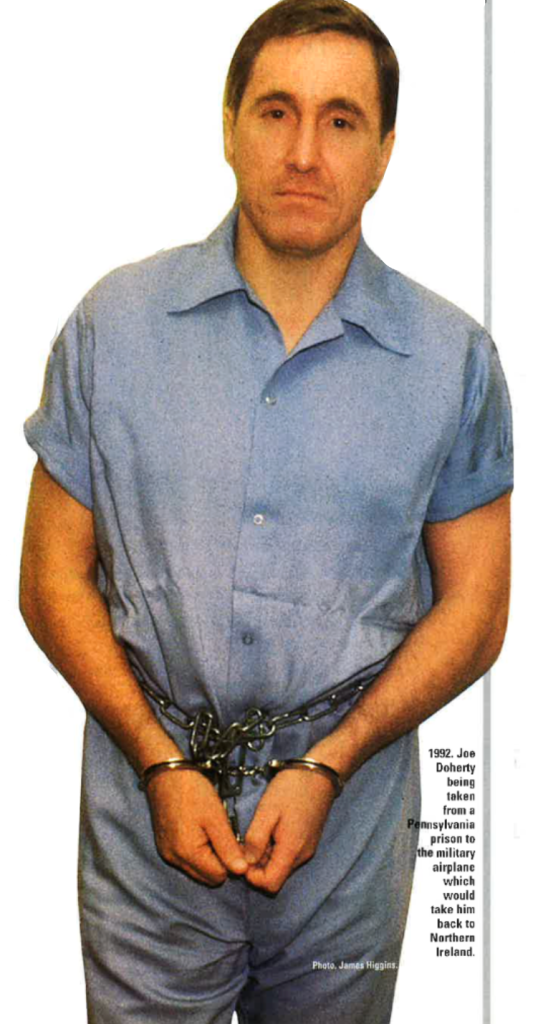

Doherty was deported from the U.S. in 1992, taken from a Pennsylvania prison cell before dawn and escorted by armed guards to a specially-appointed military airplane. It would take him back to where it all started for Doherty — Northern Ireland. On H-Block Three, a bunk was waiting.

Doherty is no longer famous; he is now just another of the hundreds of IRA men still doing time. But there was a time, in the late 1980s through the early 1990s, when the mere mention of his name sent hundreds and occasionally thousands to the streets of New York. It was in that city’s Manhattan Correctional Center that Doherty spent most of nearly nine years, while he and his New York attorneys fought a British extradition request all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

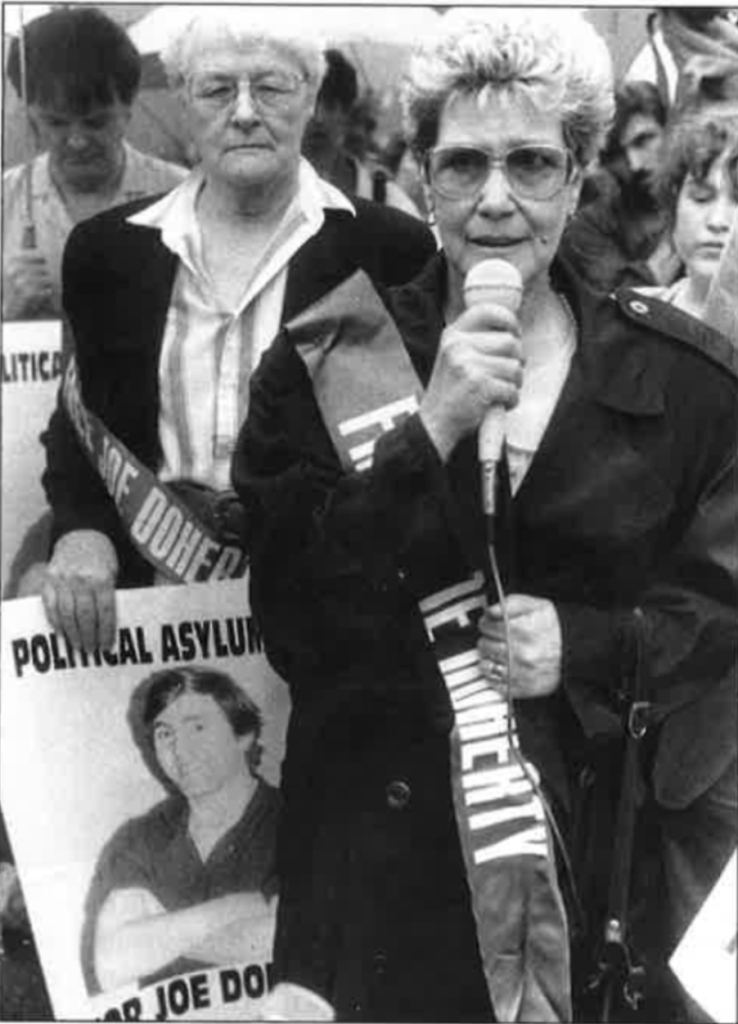

Doherty and his New York attorneys — Steven Somerstien and Mary Pike — won many battles, as court after court refused to extradite Doherty because of his status as a political, rather than criminal, prisoner.

But Washington and London eventually won the war. The case was repeatedly appealed and U.S. extradition law even rewritten, especially for Doherty. In the end, a loophole was used so as to merely deport Doherty, rather than extradite him. Since then, Doherty has sat on H-Block Three and on other wings of the Maze. After years of being hailed as a hero in New York — where even the former mayor, David Dinkins, dedicated a lower Manhattan street in his name — Doherty was just another jailed Provo in the Maze.

Yet Doherty’s worst indignity was still to come: months after his deportation from the U.S., the Northern Ireland prison authority — an arm of the British Government — announced it would not grant Doherty credit for the eight years and eight months he spent imprisoned in the U.S. A Belfast court upheld the decision, even though Doherty was not charged with a crime in the U.S. and served those years at the behest of the British Government, which was pursuing a lengthy and eventually failed bid for extradition.

“That was the one that broke my heart the most,” Maureen Doherty, Joe’s mother, recalled. “We still don’t know for sure when we’ll see our Joe.”

“Our Joe” suddenly appears, from behind yet another few walls of Plexiglas.

“Howya doing, welcome to the home-stead,” Doherty says, escorting me into a visiting room with plastic benches. There are other prisoners sitting at other benches, with other visitors: mostly women with fresh hairdos and Sunday dresses. Everywhere, there are kids, running, screaming, and eating candy.

“How do you like your tea?” Doherty asks.

Joe pours two cups from an urn at the end of the room, and we sit down. He is dressed in a grey-and-green striped Adidas shirt and blue jeans, the street clothes that were part of the hunger strike demands, in an effort to resist British Government attempts to “criminalize” the IRA.

“Cigarettes,” he laughs, accepting the only gift the guards will allow you to bring in. “I gave them up last year and, well, it was tough alright. I’ll take them though — there’s a few boys on the block who could use `em.”

Doherty’s famous American accent — picked up from hundreds of New York criminals with whom he lived in the MCC — is almost entirely gone. Occasionally his voice flattens into broad American vowels, especially after speaking with this visiting New Yorker for two hours. But he is nowhere near the days of his forced return in 1992, when fellow inmates in the Maze jokingly called him “John Wayne” or “Pacino.”

“We were watching that movie Once upon a Time in America there not long ago,” Doherty says, smiling, referring to the Robert DeNiro/James Woods gangster flick. “The boys started slagging me pretty bad, saying `Hey Pacino — get in here to do the translations.'”

Tape recorders are forbidden, and over cups of tea we chat informally about mutual acquaintances in New York. He asks what’s been happening in the case of another famous prisoner formerly at the MCC — John Gotti.

“I heard about Gotti alright, heard he’s having a rough time, where is it — Illinois or somewhere?” Doherty says.

Doherty and Gotti lived on the same block in the MCC for over a year, during which time they became friendly. Doherty says Gotti was very well-read and curious about Irish politics. As recorded by the New York City tabloids at the time, the jailed-for-life Mafia boss had a suit of clothes made for his Irish friend. The story added to Gotti’s reputation as “The Dapper Don.”

“He said to me one day, `You’re not going to go into court dressed like that,” Doherty recalled. Soon, Doherty’s measurements were taken. The suit was tailored and delivered. Where is it now? “‘The guards took it from me, they stole it I think,” Doherty says, trying to remember. “Whatever happened, I don’t have it anymore.”

Doherty says there has been no mail between the former jailmates, although there has been “the occasional postcard” from other MCC graduates, including one of the Westies, Kevin Kelley.

Doherty discusses his daily routine, which includes running laps in a small exercise yard, attending prisoner debates and meetings and chatting with his current next-door neighbor, Jimmy Smyth, who was extradited from the U.S. two years ago. Doherty is working on a university degree in economics. “It’s a lot harder than I thought it would be,” Doherty says.

The small-talk is enjoyable, but there is no escaping the topic consuming all of Northern Ireland. Within 18 hours of my visit, voters would begin turning up at polls across Northern Ireland and also in the Republic of Ireland, where they will essentially be asked to endorse or denounce what has come to be known as the “Good Friday Agreement.”

“This is the way forward, that’s how I see it,” Doherty says, speaking of the next day’s vote.

“The Sinn Féin leadership was allowed into the jail here to speak to us in a mass meeting for the first time.

Martin McGuinness was in here and he explained it all to us. There was much debate of course, but in the end the prisoners here are overwhelmingly in support of the leadership. The IRA prisoners have given their support.”

Doherty said that concerns among the prisoners mirrored those among the large republican “family” — those beyond the walls of the Maze. They too heard the cries of “sell-out,” they heard the allegations that this would be an untenable compromise for republicanism. They heard that this, after all, was not what their comrades had been killed for.

Doherty admits that there is a part of all those arguments that is true, but he repeats his statement: “This is the way forward.”

But is the Good Friday Agreement — with its scrapping of Articles 2 & 3 and also the establishment of a new six-county government body at Stormont — was this what Doherty had fought for all those years ago?

“When I was younger I really thought we were going to push the Brits out, physically,” Doherty says. “I thought we’d push them out into the sea, raise the Tricolor over Belfast City Hall and have a democratic, peaceful Ireland for all. But it’s just not as easy as that.

“In 1986, we entered Leinster House [the Parliament of the Irish Republic] and we never thought we would have done that either,” Doherty says. “Now we have this Assembly. It’s about evolution.”

Does he not have a problem with Sinn Féin members entering into a newly-founded Assembly at Stormont, identical in some ways to the Stormont Assembly that was torn down at the start of the Troubles? Doherty speaks of a “movable republicanism.”

“When Alex Maskey went into Belfast City Hall there was an uproar among some people just like there is now,” Doherty says, speaking of an old friend from West Belfast who is a Sinn Féin councilor. “There was talk of him having to take all sorts of pledges and vows, and in the end he stated a disavowal of violence. How can you disagree with that?”

Isn’t it natural, though, that a group of imprisoned men such as Doherty and his H-Block neighbors would support something — anything — which might get them out of jail sooner? After all, Doherty has served 21 of his 43 years on this planet behind bars.

“Absolutely not,” Doherty says. “That just wouldn’t happen. If that were true, we could have been out of here a long time ago if we just played the game. I myself could have been out years ago, except I refused to give in to them on the extradition. You think we’re all going to just give up now? We’re going to follow the Sinn Féin leadership because its the right thing to do, not because we can get out of here.”

Doherty does concede that, among the H-Blocks, there is a worry that IRA prisoners will be forced to sign some sort of pledge as a condition for early release, under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.

“Our worry is that they’ll make us sign some sort of pledge, make us take some kind of oath in exchange for early release,” Doherty said. “But if that arises, we’ll just have to figure out how to deal with it.”

He is asked about his impressions of the 32-County Sovereignty Committee, the “True IRA” and the other republican dissidents who have verbally and physically opposed the Sinn Féin leadership’s strategies in agreeing to the Mitchell Principles and also supporting the Good Friday Agreement.

“What I would say to them is, what are they [the `True IRA’ and the other armed dissident groups] going to be able to do that the IRA hasn’t done in 30 years?” Doherty says. “What do they think they’ll be able to achieve that the IRA wasn’t able to achieve over all this time?” Doherty has particular difficulty with the stance of the 32-County Sovereignty Committee, which is led by the sister of the late hunger-striker Bobby Sands and which argues that the current Sinn Féin strategy is a sellout. Doherty admits that their brand of absolute republicanism is similar to what he and other republicans used to endorse.

“It’s hard to argue with them because they’re using the same arguments that we were using 10 years ago, even five years ago.” Doherty says. “But we’ve got to move on. They’re using a document from 1919.”

Doherty dismisses some of the loudest of Sinn Féin detractors, and endorses the actions of an old comrade, Belfast man and current New York resident Gabe Megahey, who has confronted dissident representatives in the U.S. and has defended the Sinn Féin leadership.

“First of all, a lot of these people haven’t been around the movement in 20 years,” Doherty says. “And guys like Gabe have been through it all. There are plenty like him in here. I’ve been very impressed with how much unity there is among the men here behind the leadership.”

Does he see a day when the IRA will move against the smaller but increasingly noisy dissident groups? Within 48 hours of our talk, dissident republicans were being blamed for two explosions in the North, and a pair of men were stopped at the border with nearly 1,000 pounds of explosives.

“I don’t see that happening, I don’t see that as necessary,” Doherty says. “I remember the feuds in the early 1970s, the feuds we [the IRA] had with the Officials [the Official IRA, a long-gone splinter group]. They’d start out as fist fights and then escalate, and then people got guns. Let’s hope not, and I don’t think it will come to that.”

Doherty’s brand of “movable republicanism” is nothing new — though he is one of the longest-standing and most faithful IRA members, he has shown a penchant for irritating the purists. In 1986, Doherty — from behind bars in the MCC — had a newspaper spat with old-time republicans in New York such as Michael Flannery and George Harrison, who denounced Sinn Féin’s decision to enter Leinster House.

“I remember they were saying, who is this young punk and who does he think he is?” Doherty recalls.

More famously, Doherty was fired by his editor at the Irish People newspaper after one of his weekly columns contained a mild criticism of an IRA bombing in 1991. The republican purists who ran the paper at the time objected to Doherty’s questioning the IRA, and fired him. Those editors — who are currently vocal supporters in New York of the new dissident groups — were in turn fired from the paper for interfering with Doherty’s column, and Doherty was reinstated.

“I questioned whether it was good strategy for the IRA to bomb Musgrave Hospital, following a People editorial in which they praised the Musgrave bombing, I just said, we should think about these things and be able to argue them freely, whether they’re the right thing to do.”

Doherty laughs when told that his Irish People editor — New York radio broadcaster John McDonagh — has spoken in support of the 32-County Sovereignty Committee, using the same pro-debate argument. Clearly, Doherty remains loyal to his membership in the republican movement, but the republicanism he espouses is one that is capable of change.

“I just don’t know how you can go on basing everything on a document from 1919, or 1965 or whatever,” Doherty says. “Something’s got to happen to get us to the next level.”

Does he have any regrets? After all, 21 out of 43 years behind bars is a long time. “No, I don’t even think along those lines,” Doherty says. “If I did I’d go crazy. You can’t live your life like that.

“Maybe,” he laughs, “if I could do anything over I wouldn’t have shown up that day for work at Clancy’s [the Manhattan bar where he was arrested in 1983]. But that’s about it.”

For now, Doherty’s biggest focus is his college degree, which he hopes to complete by the end of the year. Does he ever think about what he’ll do once he gets out? Doherty says he’d like to enter into some sort of community work, being an activist on behalf of the tiny and embattled Catholic enclave in north Belfast where his mother still lives. His mother, father and sisters visit frequently, as do old friends from New York and even older friends from Belfast.

Does he ever think he might become a prisoner-turned-politician, like Sinn Féin councilor Gerry Kelly?

“Mmm, maybe,” smiles Doherty. “We’ll see when I get out.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September/October 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply