How journalist Januarius Aloysius MacGahan, the son of Irish immigrants, helped cause a shift in the European balance of power that made the liberation of Bulgaria possible.

“Since my letter of yesterday, I have supped full of horrors. Nothing has yet been said of the Turks that I do not now believe; nothing could be said of them that I should not think probable or likely…But let me tell you what we saw at Batak.”

With these words a young Irish American war correspondent, Januarius Aloysius MacGahan, opened his description of the Bulgarian town of Batak three months after it had been razed, and its rebellious people massacred, by Turkish irregulars. MacGahan’s descriptions in this and subsequent dispatches slipped out of Turkish territory in 1876 sent shock waves through Europe, shook British foreign policy to its foundations, and helped cause a shift in the European balance of power that made Bulgaria’s liberation possible. It is an incredible story but it is almost forgotten today, as is MacGahan himself, in his own country.

Januarius MacGahan was born June 12, 1844, on a farm near New Lexington, Ohio, to Irish immigrants James and Esther Dempsey MacGahan. He was the oldest of three sons. His devoutly Catholic parents had been married on the feast of St. Januarius. New Lexington, in the hill country of southeastern Ohio, had, for a rural area, a sizable number of Irish Catholics, brought west by road construction and then by the railroads. MacGahan’s father died when he was six, leaving Esther and the boys to straggle with the hard-scrabble hill farm. At age sixteen, Januarius headed west to join a cousin in Huntington, Indiana, and find employment to help support his impoverished family.

He took a job as a clerk, wrote occasional “space rate” pieces for the local newspaper, and sent money home. After three years, he moved on to a better clerking job in St. Louis. There, he cut a serious figure, saving money and reading classic literature in his off time. But he regarded his time there as existing rather than living; with some money saved beyond what he needed for his family responsibilities, he formed the idea of going to Europe to learn languages and/or law. Taking leave of his family, he fetched up in an artists’ colony in Belgium and spent the next two years learning French, supporting himself by giving English lessons, making avant-garde connections, and watching as neighboring France drifted towards the Franco-Prussian War.

Following the outbreak of the war, the by now impecunious but French-speaking MacGahan managed to get a job as a junior correspondent for the New York Herald, the flamboyant newspaper that had, shortly before, sent Stanley after Livingstone. The war was short, punctuated by decisive Prussian victories; MacGahan saw little action but, following the French surrender, went on to Paris to cover the actions of the new French government. He was in Paris when, in the aftermath of defeat, radical elements of the City Militia defied the government, touching off the 70-day rebellion known as the Paris Commune.

MacGahan, relied on for “heavy interpreting,” quickly made the acquaintance of some of the key leaders of the Commune, including its top military commander, and was able to cover the action from the Communard front lines. He sent a series of dispatches vividly describing Paris in the throes of war and revolution, and achieved a by-line in the Herald and some notoriety in New York and Europe. He also nearly achieved an early end to his career. In May of 1871, with Communard resistance collapsing, he and another Herald correspondent were arrested by government forces. This was a potentially life-threatening situation, since the Army was mopping up by summarily executing Commune supporters. MacGahan managed to get word to the American ambassador, who hurried to get their release. MacGahan characterized the often brutal suppression of the Commune tartly: “Here is [the government’s] system of putting down a revolution: Smith burns my house and for revenge I kill Jones, Brown, Green, and their families.” He believed that the Commune showed the excessive cost of overcoming dissent by force rather than reason.

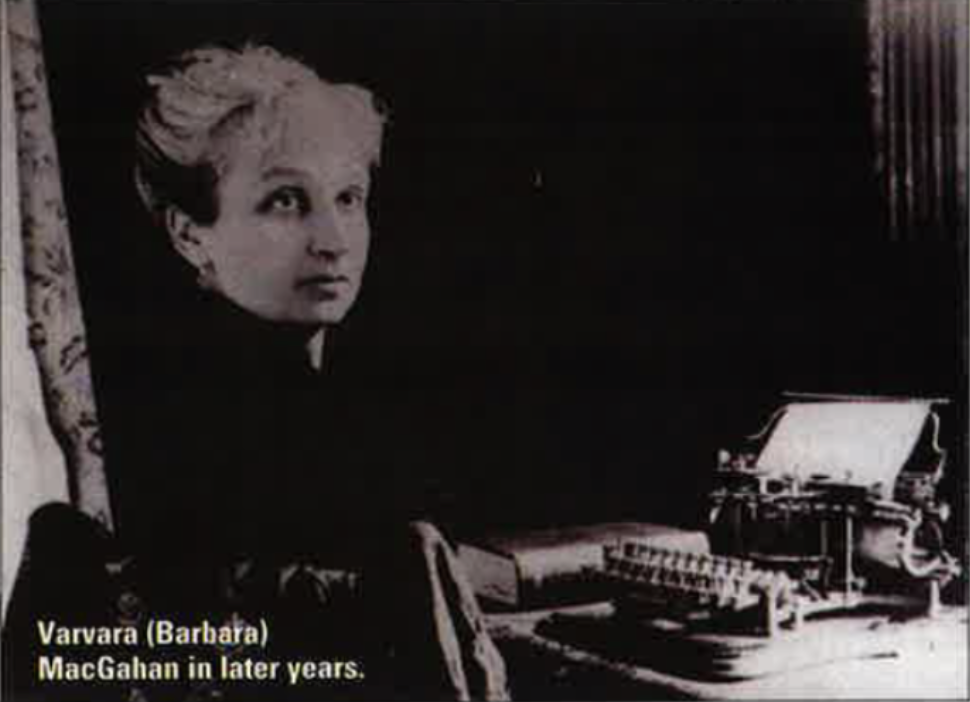

Following the fall of the Commune, the Herald sent its now notable reporter east to Yalta to cover the winter court of Russia’s great reforming Czar, Alexander II. There, he quickly fell in with the young Russian officers assigned to court, who were eager for information about the attempted revolution in Paris. A seemingly improbable pal for Russian aristocrats, MacGahan found them somewhat different from their autocratic reputation, forged friendships, learned Russian, and courted and finally married the daughter of an impoverished but aristocratic Russian family, Varvara Elagin. Awaiting a new assignment, he and Varvara set up housekeeping in London, for her to learn English. The assignment came soon.

Gordon Vincent Bennett, publisher of the Herald, ordered MacGahan to use his knowledge of the Russian military to find a way to join the Russian forces then forming in remote Central Asia to march on the desert-bound Moslem citadel of Khiva. As in a more recent war in that part of the world, correspondents had been banned from the forward areas.

Unable to get permission, MacGahan and a young American diplomat, Eugene Schuyler, also on an information-gathering mission, made a hard journey into Central Asia, arriving at the Russian outpost of Khazala shortly after the main column, commanded by General Kaufman, had left. Denied permission to follow, MacGahan, undaunted, left Schuyler and struck out into the vast Kyzl Kum desert, accompanied only by three native guides, hoping to catch the Russian army in mid-march. He had entered the territory of the nomadic Kirghiz people, reputed in more civilized parts to be “robbers and murderers.” He found them unfailingly generous and hospitable, and suspected that any attempt to Europeanize them would lower their standards.

His small party advanced through the desert, stopping at Kirghiz camps where they shared provisions and MacGahan bagged game for communal feasts. But if the desert people were hospitable, the desert itself was not, and MacGahan’s party pushed on through sweltering heat and despite increasingly scarce water. After crossing more than 500 miles of desert, the last thirsty and harrowing days spent avoiding Cossacks sent to bring him back and Turcoman tribesmen who were scouting the Russians for the Khan of Khiva, he arrived at the Oxus River, edge of the great Central Asian oasis dominated by Khiva, as Kaufman’s army was forcing a crossing against the Khan’s forces.

But word of MacGahan’s daring desert crossing, illegal as it was, had arrived before he did. He was welcomed by the Russian officers, who thought his feat was nearly impossible, and shortly was presented to both General Kaufman and the Grand Duke Nicholas, who had joined Kaufman. Far from having him arrested, Kaufman gave the “molodyetz” (daring fellow) an interview and described the entire progress of the campaign.

Stripped of its desert shield, Khiva surrendered in short order. MacGahan surveyed the previously forbidden city, finding it not very impressive, and celebrated with the Grand Duke and his regiment. And in probably his most outrageous exploit, he climbed into the Khan’s palace, which had been placed under guard by Kaufman, and, after blundering through a maze of darkened corridors, found the harem, which had been abandoned by the fleeing Khan, and obtained an interview of sorts with the amused head wife.

The Khan shortly returned and accepted Russian overlordship; and Kaufman undertook a punitive campaign against the Khan’s more valiant allies, the Turcoman tribesmen of the deserts to the south. Kaufman marched when the Turcomans said they couldn’t pay the heavy indemnity he imposed on them; but, though he admired Kaufman, MacGahan had no illusions about what he was doing: “They were an independent people who flouted all authority — the unpardonable sin in the eyes of the Russians.”

MacGahan watched as the Russians torched the Turcomans’ humble settlements at the edge of the desert; the tribes-people had fled with all that their wagons could carry. And he was nearly caught in the middle when the Turcoman horsemen suddenly turned and attacked. The dating attack was smashed; then, as the Russians overtook the fleeing mass of people, they abandoned their baggage and scattered. The baggage torched also, the Russians left the Turcomans to digest the lesson. MacGahan thought the Russian soldiers generally behaved decently — many of the officers, as well as he himself, rescued lost children — but the overall effect of the campaign was somber. Noting a Turcoman boy looking after several other children, while the bodies of three men, probably related, lay nearby, he wrote sadly: “Twenty years hence, some of the `Kaffirs’ will probably feel how well the child had learned to hate them.”

In Europe, news of the campaign was received with interest; the British in particular watched Russia’s advance in Central Asia (bringing it, in their minds, closer and closer to India) sharply. Back in London with Varvara, MacGahan wrote up the war in his first book, Campaigning on the Oxus, which was published in July of 1874, to universally good reviews.

Almost immediately thereafter he was dispatched to Spain, to cover a rebellion that had broken out over a long-standing Spanish dynastic dispute. He joined the forces loyal to the pretender to the Spanish throne, Don Carlos, and interviewed Don Carlos himself twice, sending back a series of dispatches that covered the entire “Carlist” theater of operations. But the Carlist rebellion subsequently collapsed, and MacGahan was arrested for wearing a distinctive Carlist beret, along with a correspondent for the New York Times, who was unlucky to be with him.

They were locked up in a makeshift jail — an outhouse, in fact; it was another potentially life-threatening situation, and the Herald thundered about the violation of the press, their American passports, and the “disgusting indignities” that MacGahan and his comrade were subjected to, and the American Consul again rode to the rescue. But MacGahan himself kept his perspective, and on release headlined his first dispatch “It was all my fault” and then went on to grumble about the hick Spanish police chief who had never heard of the New York Times.

Following the Carlist War, the birth of his son Paul, and an Arctic voyage, he wrote a second book, Under Northern Lights. But in the meantime, events were taking shape in the Balkans that would forge his destiny.

Bulgaria, a prosperous country in the Middle Ages, had endured five centuries of role by the Moslem Ottoman Turks that saw its Orthodox Christians reduced to poverty and servitude under Ottoman taxes and landlords, its institutions crashed and its culture and customs degraded. But in the nineteenth century, it underwent a grassroots renaissance, the Bulgarian Resurgence, that led inevitably to nationalist ferment and finally, in 1876, to rebellion. However, the rebels did not even enjoy the temporary successes of the Irish peasant rebels of 1798. The Ottoman army, aided by Moslem irregulars called Bashi-Bazouks, and armed with modern weaponry, crashed the rebel forces before they could advance far from their own villages. Chetas, or guerrilla bands, who retreated into the mountains with the Turks in pursuit, fared little better. And then, with the rebellion in its death throes, rumors began to reach Western Europe of Turkish atrocities. Back in Paris with Varvara and Paul, MacGahan couldn’t interest the Herald in sending him. But the London Daily News, the British Liberal newspaper founded by Charles Dickens, was interested; and in June 1876 MacGahan arrived at the Ottoman capital, Constantinople. Accompanied by his old friend Schuyler, now U.S. Consul there, he went directly on to Bulgaria.

The authorities, denying that any atrocities had taken place, tried to keep MacGahan and Schuyler from reaching the sites of the rising by ordering that no horses or equipment be provided to them. Distraught Bulgarians defied these orders and mocked the official denials. And on August 1, 1876, the two Americans reached the mountain town of Batak, a rebel center which had surrendered to the Bashi-Bazouks. His next dispatch, carried out of Turkish territory by courier, described what they saw in angry and unrelenting detail.

Entering a town that from a distance looked to him like the rains of Pompeii, he first saw a cairn of human bones, marked by scraps of women’s clothing. Skulls were scattered about, all separated from the skeletons. In the mined town he saw skeletons everywhere, some with putrid flesh yet attached. At one point he saw partly charred bones. Some of the survivors had tried to cremate some of the bodies but were unequal to the task. In the center of the town was its burned out church, where townspeople had taken refuge. Here he found human remains covering the churchyard, from wall to wall, three or four feet deep. The smell, three months after the fact, made it impossible to continue. Survivors (there were 1,000 or 1,200 in what had been a town of 8,000) sat vacantly by the remains of their families, or wandered about wailing. The cairn of bones, he found, was the remains of “200 young girls who had first been captured and particularly reserved for a worse fate.” He concluded, now in a fury, “Then, when the town had been pillaged and burned, when all their friends had been slaughtered, these poor young things…whose very outrages should have assured them protection, were…coolly beheaded, then thrown in a heap there and left to rot.”

MacGahan sent a series of ten dispatches out of Bulgaria. He pointed out proof “on all sides”(soon confirmed by Schuyler and others) of the atrocities that were to become known to history as the Bulgarian Horrors. The readers of the Daily News were shaken, and even Queen Victoria was momentarily disturbed (she concluded it had been Russia’s fault, for encouraging the Bulgarians). Public meetings denouncing the Turks were organized in several British cities, and the Tory government of Benjamin Disraeli, whose foreign policy in Eastern Europe was based on supporting the Ottoman Empire as a counterweight to Russia (Russia was thought to be a threat to the “balance of power” that favored British interests), found itself on the defensive, at home and abroad. The Tories had scoffed at the early reports; they were now reduced to arguing that the reports were exaggerated. And MacGahan’s origins were not lost on them; as one parody of official British reaction put it: “The man who first unveiled the conduct of our Turkish allies is either an Irishman or an American and…you must be cautious in adopting his statements.”

Disraeli’s policy came under furious attack by British Liberals, and outright military support for Turkey, as Britain had provided in the Crimean War, became impossible. And in Russia, both public and official indignation were boiling over.

Tied to the Bulgarians by Orthodox religion and Slavic origin, Russia also regarded itself as protector of Eastern European Christians, and saw the Balkans as a Russian sphere of influence. When the Ottoman Empire refused to sign an agreement protecting its Christian subjects, Czar Alexander declared war, and MacGahan joined the Russian forces for the last great story of his career. The Herald, embarrassed by the sensational story their man had broken for another newspaper, agreed to run his dispatches jointly with the Daily News; and Varvara made arrangements to translate them for the Russian daily, Golos.

The Russians succeeded in misleading the Turks and crossed the Danube into Bulgaria unopposed. With MacGahan riding along, a Russian advance force raced south through the Balkan Mountains; Bulgarian volunteers flocked to the Russian colors. But the real barriers to Russian conquest, unlike at Khiva, would not be physical ones. Before the Russians could consolidate their hold on northern Bulgaria, a capable Turkish commander, Osman Pasha, force marched an army of 50,000 from the Serbian border and occupied the crossroads town of Plevno. He beat the Russians there by a day; and when they got there he had dug in, and when they attacked, they were mauled.

The advance force retreated north under attack, and MacGahan, hobbled by a broken leg from a fall from his horse, went on to join the main Russian army near Plevno. There, on the Czar’s birthday, he watched as the Russians made their move and threw their full force against Osman’s defenses. Russian formations advanced on three sides, to be met by a mass of well-directed Turkish fire from protected positions. One Russian force, commanded by MacGahan’s friend General Skobelov, stormed the Turkish redoubts defending the northwest approaches -and then, as no other Russian units were able to break through, came under attack from two sides, and was forced to retreat, again in a hail of fire.

The losses were appalling. Modern firepower was making attacks in formation increasingly suicidal — a fact that had been repeatedly demonstrated, if never quite grasped by the generals, in the American Civil War. MacGahan filed a series of dispatches both vividly describing the carnage before Plevno, and harshly criticizing the Russians for attempting massed frontal assaults. His Turkish War dispatches described the human costs of war, and criticized strategy on that basis — also something of a novel idea. But if he blasted Russian strategy, he never wore out his welcome with the Russians; he was warmly received in every Russian command. And among the Bulgarians, it was said that he could enter any village, indeed any home, and be assured of a meal, no matter how hard circumstances were.

Varvara settled in Brooklyn, and made a career of writing on America for Golos. She died in 1908. Paul went to Columbia and became an engineer. As for MacGahan himself, New Lexington held periodic commemorations, attended by thousands, but as time passed these grew smaller and less frequent; and elsewhere he was gradually forgotten, relegated finally to the status of a local hero, comparable, say, to Benjamin Hanby of nearby Rushville (“Welcome to Rushville, home of Benjamin Hanby, composer of `Darling Nellie Gray'”). But the Bulgarians didn’t forget him.

“A pilgrim from the ends of earth I come / To kneel devoutly at your lowly tomb/To own our debt, we can never repay/To sigh with gratitude, thank God and pray / To bless your name and bless your name / For this I came.”

So wrote Bulgarian poet Stoyan Vratalsky, in a poem he left on MacGahan’s grave. MacGahan is remembered in Bulgarian histories; his role in Bulgaria’s liberation was told to Bulgarian children, even in Communist days. Streets are named after him in Sofia and Plovdiv, the two largest cities. A bust commemorates him in Batak, and an annual Mass reportedly is offered for him in the ancient cathedral in Turnovo. And in America the efforts of Bulgarian Americans (who joined forces with history-minded locals) have led to the erection of a statue of MacGahan in New Lexington, and to small annual commemorations that are now held there.

In our time, massacres and politically inspired genocide have not become less frequent. And the telegraph has given way to electronic mass media and global satellite relays that bring news of the most distant events almost instantaneously. Yet no correspondent in recent memory has changed the way the world responded to such an event the way MacGahan did. The reason for this suggests a reason that his life represents more than historical trivia. Newsweek, for example, had coverage of the Rwandan massacres; contrast it with MacGahan’s dispatch from Batak. The reader will see bodies floating in Lake Victoria, but won’t get too close.

And the writer won’t know, and won’t try to find out, who they were. MacGahan did. He not only brought his readers to the site of the massacre, he stripped away their psychological distance, first in his disturbing coverage of the horrid details, then in putting those details in the context of the victims’ lives. To the Ottoman government, the village girls at Batak were the cost of doing business in a rebellious Christian province. To the British government, they were an extraneous issue, complicating policy matters of wider import. But MacGahan saw them, virtually, as the girl next door; which is what they were to the Bulgarians. And they never forgot him for it.

This removal of psychological distance characterizes all his work, whether about Paris Communards, Russian officers, desert tribesmen, or the girls at Batak. Perhaps there is something especially Irish in this, and perhaps this is why, like MacGahan, Irish men and women have helped in the liberation of so many other people’s countries. But it is something that remains lacking in our electronic global “village.” And it remains a good reason for remembering the once famous young Irishman from Ohio.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November/December 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply