From poor immigrant acceptance – the struggles and triumphs of an Irish American family

My County Mayo-born grandfather, David Fleming, could not read or write. He had a brogue so thick I couldn’t understand a word he said. But I knew one thing. He was Irish and proud of it. He had a favorite poem that he made me memorize and recite when I was six. It was called “Why I Named You Patrick.” I can only remember one verse of it.

When you wear the shamrock, son,

Be proud of your Irish name.

No other one I know of

Can stand for greater fame.

Old Davey was a big bulky man, with thick arms and solid shoulders. He looked like he could put his fist through a door if he got mad. He liked jokes about fighting Irishmen. One of his favorites was about the Irishman who got shipwrecked and drifted up to the shore of an unnamed country. “Is there a government in this place?” he asked the natives. They said yes. “I’m agin it,” the Irishman said. The joke had some personal meaning to Davey. In 1870, when he arrived in Jersey City, the place was run by Anglo-American Protestants, better known these days as WASPS. No Irish Need Apply signs were plentiful. During World War I, when an Irishman was promoted to foreman at the Colgate factory, it made headlines in the local paper.

Old Davey, as I called him privately, was an angry man. He would not tolerate a bag of Lipton’s tea in the house. He disliked Thomas Lipton because he was English and flaunted his wealth, winning all sorts of prizes on his famous racing yacht.

Davey also disliked insurance men. Around the turn of the century, there was a big exposé about how the insurance companies had cheated millions of poor people by collecting fifty cents a week from them long after they had paid up their little policies.

Fifty cents was real money to David Fleming. It was what he had gotten paid for a day’s work at Standard Oil when he started out there as a laborer. He told my Aunt Mae, with whom he lived after his wife died, that he never wanted to see an insurance man in the house.

My Aunt Mae used to meet the insurance man out on the corner. One day someone’s schedule got confused. The insurance man came to the door of their second-story flat.

“Metropolitan Life!” he chirped as Davey opened the door.

Wham! Davey punched the poor guy down a whole flight of stairs. Aunt Mae had to change insurance companies.

My father always referred to Davey as “the old gent.” He never said the old man. Or my old man. I sensed there was a lot of respect in his choice of words. Now I think I know why. The old gent got up and went to work at Standard Oil every day for fifty years. He never drank his pay. He cared about his wife and kids.

When my publisher, W.W. Norton, started a series called The States and the Nation, they asked me to write the history of New Jersey. My agent, a Wasp from California, said he didn’t think the money was good enough. I said: “My grandfather couldn’t read or write. Now they’re asking me to write the history of the state. I’ll do it for nothing.”

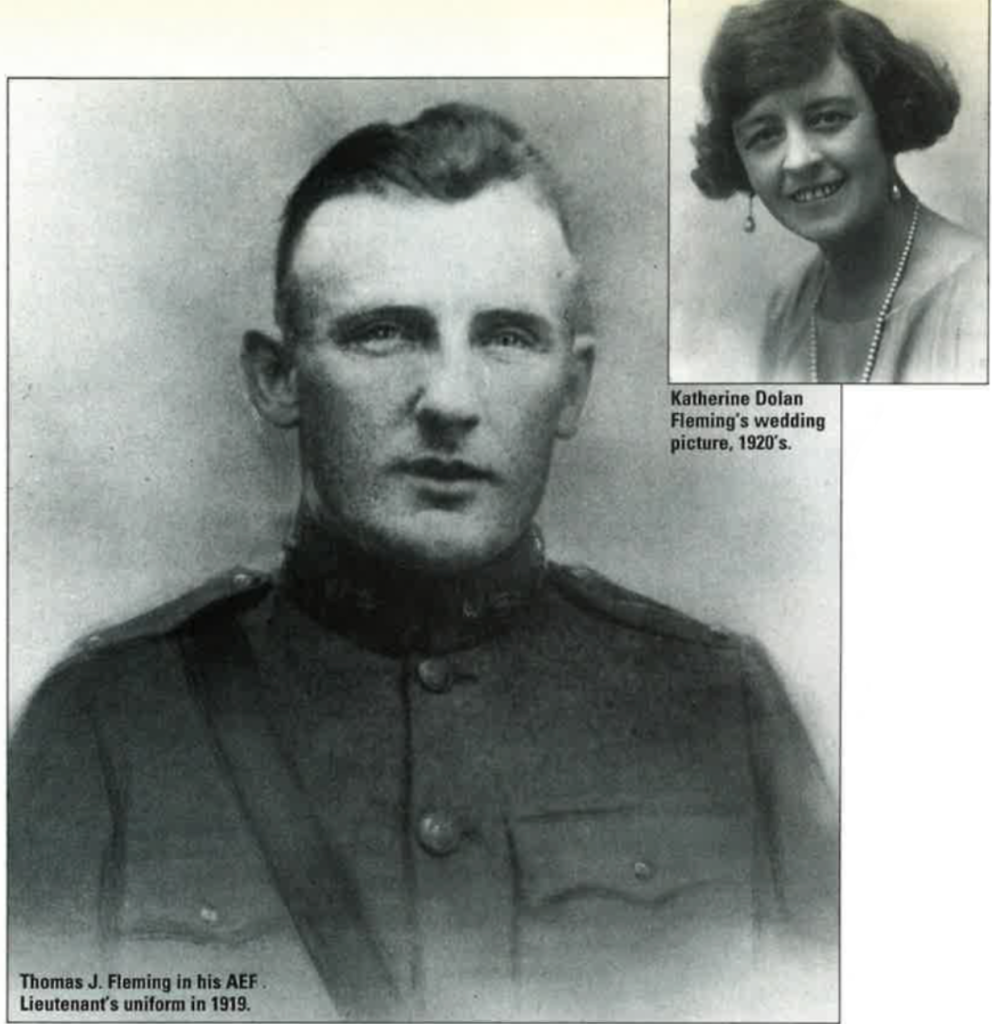

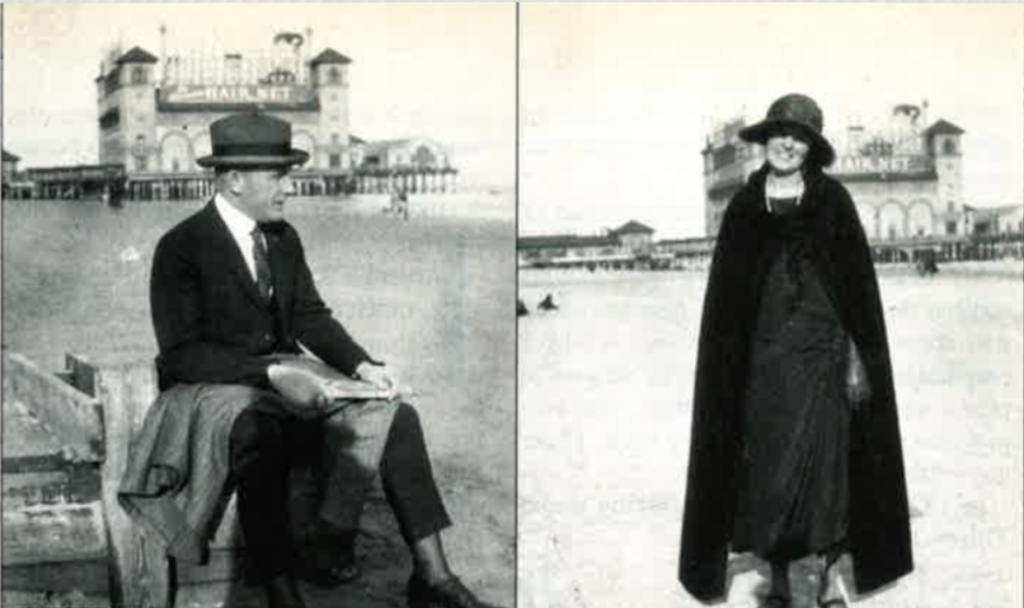

My mother didn’t like Davey very much. She called him a Thick Mick. She never said that to my father, of course. But that’s what she called him to me and my brother. My mother was what they used to call lace curtain Irish. She was a beautiful dark-haired woman, a stylish dresser. Her father had been a pretty prosperous carpenter. Her mother was the daughter of a schoolteacher in Ireland. She could read and write and my mother was one of the few Irish-Americans to graduate from Dickinson High School and spend a year in normal school to earn a teaching certificate.

My mother considered culture more important than a well-decorated house — though she liked that too. She read the latest novels, she loved the theater, especially the plays of Eugene O’Neill. She started taking me to shows when I was seven or eight. She had a lot to do with making me a writer.

The kind of Irish jokes she liked were about thick micks. One told how this Irishman, just off the boat, was invited to a banquet. They served a consommé. He had never seen anything like it, but he drank it. They served a salad. This baffled him too but he ate it. Then came a lobster. He threw down his napkin and left the table. “I drank your wather and I ate your grass,” he said. “But I’ll be damned if I’ll eat that bug!”

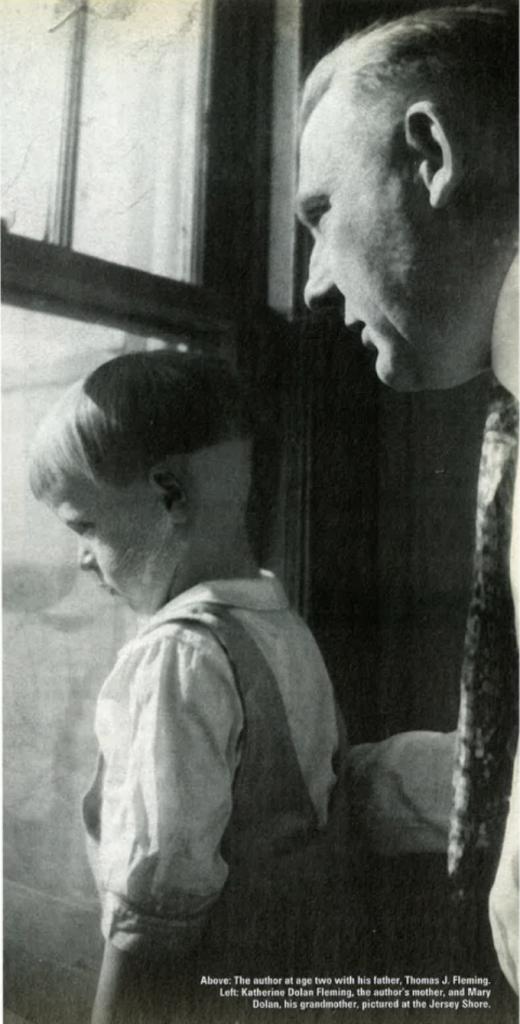

My father, Thomas J. Fleming, whom everyone called Teddy — that was my Jersey City name too — was built like my grandfather, big hands and arms and the same shoulders, but somewhat shorter.

His side of the family told me what it meant to grow up Irish and poor in Jersey City. During the summer, while he was still in grammar school, he and his brothers Dave and Charlie used to work in a watch factory next door to their tenement on Pacific Avenue. Each morning they faced a clerk in a high white collar who looked down at them from a tall desk and asked: “Protestant or Catholic?”

If you said Protestant, even though the map of Ireland was on your face, you got a job. If you said Catholic, the clerk said: “No work today.”

You can imagine what David Fleming thought of this Protestant supremacy act. It gives you a glimpse of why the Irish supported a politician named Frank Hague, who took over the city in 1917 and soon made it clear that no one was going to push the Irish around anymore.

Before Hague arrived, my father’s ambition when he was a kid at All Saints School was to become a major-league baseball player. He loved the game. Some mornings he and his friends would get up in the dawn and play a few innings before school began. Sometimes in March they had to shovel snow off their field down in Lafayette.

I’ve always liked the name of the field — The Happy Nines.

Watching them on many mornings was a big black-robed figure — Monsignor Michael Meehan, the pastor of All Saints. When my father graduated from the 8th grade he called him into the rectory.

“What are you going to be, Fleming?” he asked.

“A major leaguer,” my father said.

“No you’re not,” Monsignor Meehan said.

“You can’t hit a curve. We’ve got too many tramp Irish athletes already. You’re going to business school.”

Thirty years later, when my father became leader of the Sixth Ward, Monsignor Meehan was still there. He called my father into the rectory again. “I suppose you’re going to work your head off to make good down here,” he said.

My father allowed that he was going to do something like that.

“Well just remenber this,” the Monsignor said. “Jesus Christ himself couldn’t keep these people happy.”

My father never became the businessman Monsignor Meehan envisioned. History had other ideas. In 1917 he found himself in the U.S. Army on the way to France to fight the Germans. He went because Monsignor Meehan and other leaders said it was a way to prove the Irish were good Americans.

He and other Irish Americans in Jersey City were not exactly worshippers of President Woodrow Wilson. They elected him governor in 1910 on his solemn promise that he would allow Boss James Smith of Newark and Boss Bob Davis of Jersey City to have the okay on patronage. The minute he got to Trenton, Wilson went back on his word.

That was a mortal sin to an Irish-American politician. They might pad the voting rolls, tolerate gambling, cut a deal or two with a local contractor. But your word was your bond. Then Wilson made a speech in 1915 in which he accused Irish and German Americans of “pouring poison into the veins of American life” because they did not like the way he sided with the English in the war that was killing millions of people in Europe.

But the Irish, including Teddy Fleming and a lot of his friends from Jersey City, went to Europe and fought the Germans. In the gigantic baffle of the Argonne in 1918, all the officers in my father’s company were killed or wounded. He was the top sergeant and they made him an instant lieutenant.

In 1968, on the 50th anniversary of the Argonne, my wife and I went to France and I followed my father’s straggle through the Argonne, using his regiment’s diary. I saw the price the Irish in the 78th Division paid to prove they were Americans.

We got to a place where the diary said they attacked La Ferme Rouge — the red farm house. It was still there. We went to the door and with the help of an interpreter introduced ourselves. The farmer, a guy built like my grandfather, had been there when my father’s regiment attacked! He had been sixteen at the time.

He took us to the trenches around the farm’s perimeter. He pointed out a nearby wood, the Bois des Loges, which the Gen had filled with machine guns. The regiment lost almost a thousand men attacking it. It was as bad as Belleau Wood, but it never got the publicity the Marines got for that show.

My father, like most doughboys, utterly despised the Marines for the way they bragged about themselves.

Back at La Ferme Rouge, the farmer broke out a bottle of Moet et Chandon and he offered a toast: “To the son of the man who freed the Bois de Loges.”

That was one of the proudest moments of my life.

My father never made a big deal about his combat days. His favorite Argonne story was about four Irish-Americans, led by a corporal named Delaney, that he sent out to patrol no man’s land one night. The two previous patrols had not come back. These guys didn’t either.

In 1920, my father was walking down Thirty-Third street in New York. Who comes toward him but Corporal Delaney. “I thought you were feeding the worms in the Argonne,” my father said.

“Lieutenant,” Delaney said. “Do I look crazy? The minute we got out there, we found a break in our trenches and ran like hell for the rear. After about a mile, we yelled `gas’ and started coughing our brains out. They put us in nice comfortable beds at the hospital and sent us home on the next ship.”

My father always shook his head over that one. “I might have done the same thing if I was in his shoes,” he said.

When he got back to Jersey City, my father discovered that getting commissioned in the Argonne had changed his life. Frank Hague was looking for war heroes to give his organization voter appeal. Teddy Fleming soon became a politician. Doc Holland, the leader of the Sixth Ward, made him his right-hand man.

In private, my father always strenuously denied he was a war hero. He never had much use for guys who won promotions or medals. He said he had seen too many people do things under fire to save the life of a friend and get nothing for it — except maybe get themselves killed. But he let the organization add “commissioned officer” in his biography every time they ran him for office.

He meant what he had told Monsignor Meehan. He worked hard at being a politician. Especially during the Great Depression. Night after night, he sat in the ward clubhouse talking to people who were desperately looking for jobs. He never promised a job he could not deliver. That was basic to his Irish-American code. The people knew his word — plus his handshake — was his bond.

One night that saved his life. A man with a Slovak name appeared for the third or fourth time. My father said he would go all out to get him into the ironworkers. The man wept — and put a loaded pistol on my father’s desk. “If you turned me down again, I was going to kill you,” he said.

Almost every night after the clubhouse closed, he would spend a couple of hours in the ward’s bars, listening to political opinions, complaints, pleas for promotion at city hall or on the cops or fire department.

I remember, after he retired, trying to tell him what a good job I thought he’d done as a leader. How the kind of work he did kept a city together.

He looked at me as if I’d gone nuts. “But Teddy,” he said. “You had to listen to an awful lot of baloney.”

When I was a teenager, I used to go down to the ward for political rallies. My father wasn’t much of a speaker. He had a short set piece, which mostly consisted of telling the voters: “You are my people. Never forget that. If you need something, come to me and I’ll try to get it for you.”

He meant that too. He was one of the few ward leaders who was willing to go head-to-head with Mayor Frank Hague to get promotions and raises for his people. This often led to screaming arguments and threats of exchanging punches.

It was one way — probably the only way — to win Mayor Hague’s respect. I remember the first time I met the Mayor, who was about six foot two and looked as if he could eat you for breakfast. He mashed my hand and said: “You’re old man’s one in a barrel.”

What does it add up to? I think — or hope — it’s a kind of window on what being Irish-American was all about in Jersey City. It’s a rather surprising mix of pride and anger and a kind of ongoing conflict between the two sides of that hyphen, between Irish and American.

It wasn’t always pretty or noble. It was hard to be pretty or noble when your father made 50 cents a day — and you had to deny your religion to get a job. Things happened that made you mad — that made you want to get even.

One day when my father was a teenager he came out of All Saints Church and he met a local Protestant who said: “Hey Fleming, did you tell the Monsignor what you do to your sister?”

In ten seconds the guy was on his back in the street with about a thousand dollars’ worth of new bridgework mined. My father had to leave town for a few weeks while Monsignor Meehan cooled off the law.

But going to France, commanding men in battle, dealing with people in the ward made my father and a lot of other Irish Americans outgrow that early anger. I’ll never forget the night I realized this.

Answering the doorbell, I confronted a small snub-nosed man in a velvet-collared coat that had seen better days. He asked to speak to my father. I said I would see if he was at home.

My father was upstairs in his bedroom, dressing to spend the evening at the Sixth Ward Club. When I told him the man’s name, he frowned. “He’s the son of the guy that owned the old watch factory,” he said. “They went bankrupt last year. He’s looking for a job.”

My father went downstairs. I hung over the second-floor railing above the stairwell, expecting to hear a parable of Irish vengeance acted out. I was totally disappointed. My father greeted the man courteously and they discussed where he might find work. My father finally decided his training as an accountant might win him a slot at the IRS. He promised to put in a word for him at City Hall.

I asked my father why he hadn’t made the ruined Protestant scion crawl. Had he forgotten what they made him do at the watch factory? My father looked at me with mild disapproval. “That happened a long time ago,” he said.

Many years later, while I was writing books about the American Revolution, I came across the motto of the greatest Irish-American of 1776, Charles Carroll of Maryland. He said as Irish “We must remember — and forgive.” I was stunned to realize I had seen my father, who never got beyond the 8th grade in All Saints School, act out that profound — and profoundly difficult — advice in Jersey City.

When I was finishing my novel Rulers of the City, I found myself in a bind. The mayor of my imaginary city, which has strong resemblances to Jersey City, is trying to cope with a busing crisis. He’s the son of one of the old era’s ward leaders. His liberal Protestant wife was giving him hell from one side and his ethnic Democratic supporters were doing the same thing from the other side. The mayor finds himself wishing for the good old days, when the Organization could settle things with orders from City Hall and a few nightsticks.

In the book, the mayor digs out his father’s papers and starts to read the letters he got as a ward leader, the speeches he made. I did the same thing in real time. There were letters of thanks for favors, from canceling a bill at the Medical Center to reports on how a son or daughter was doing in a new job in Trenton or Washington. There were copies of those speeches, telling the voters of the Sixth Ward, a mix of Irish, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Italians and Blacks, “You are my people.”

The Mayor, in concert with the author, realizes the only thing worth preserving from the old organization was the caring. The rest of it, the world where all the answers were written in advance in the Baltimore catechism and the okay from City Hall — they were probably well rid of it. The caring. Caring about people of every race and creed, because they’re fellow Americans — and hopefully — but not necessarily — Democrats.

I like to think that idea, that political and spiritual reality, is what the Irish-American years have left as a heritage for Jersey City.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November/December 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply