“Imagine co-authoring a book with someone who’s been dead for 130 years,” laughs Ipswich, Massachusetts native Marjorie Harshaw Robie. “Well, that’s exactly what I’m doing and I’m enjoying every minute of it.”

Robie’s co-author, whose work she is revising and collating in the hope of finding a publisher, is County Down farmer James Harshaw, who died in 1867. Long before Anne Frank was ever heard of, Harshaw kept methodical daily records of life on his farm and in the surrounding parish.

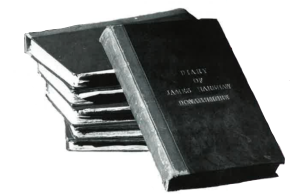

Over a century and a half after he first put pen to paper, his diaries, which spent over 100 years in at least four American states, are finally back where they belong — in Northern Ireland.

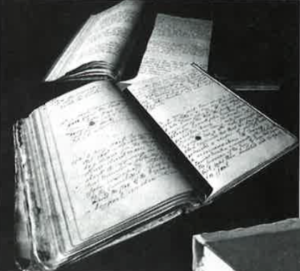

The diaries, which are believed to be unique, provide an intriguing glimpse at life in the 1800s, recording every detail from births and deaths to the weather, politics and daily farm activities.

Beginning with a narrative on February 28, 1841 which was primarily concerned with the business of running a farm, the entries were sporadic over the first few years, but by 1844, with one exception, James Harshaw wrote faithfully every day in his diary.

The story of how the diaries came to be restored to the people of Northern Ireland is one which is almost as intriguing as the diaries themselves.

It’s a story which began back in mid-1980s when a Pennsylvania woman named Sally Lowing received a call from the management at the Grove City Bank, which had been founded by her grandfather, William J. Harshaw.

The caller described a bunch of old books with the Harshaw family name printed on them which had been found in the basement of the bank. Sally agreed to take the books, and after a curious glance through them, decided to try and find who they belonged to.

She eventually sent the books to another Harshaw descendant who lived in Iowa. Karen Hickey, who had been trying to compile a family genealogy, received the volumes completely unexpectedly, and was probably the first person this century to actually sit down and read each diary from cover to cover. Enormously excited by what she had in her possession, Hickey felt that her primary obligation was to make back-up copies.

Meanwhile, up in Ipswich, Marjorie Harshaw Robie was trying desperately to locate the diaries. Having become interested in the study of family history, Marjorie was anxious to begin studying her family genealogy.

“I was only vaguely aware that my family came from Ireland because they never really talked about it. My great-grandfather, Michael Harshaw, was the Irish immigrant on my father’s side, and my mother’s parents were also both born in Ireland.”

Through her research, Robie came across a book written in 1914 by a County Down reverend which referred in passing to James Harshaw who “kept a diary for many years, in which he recorded the daily events of his life, even the most trivial being noted.”

Armed with a computer provided by her son, and a list of all the Harshaw families in the U.S., Marjorie set about trying to track down the Harshaw diaries.

Three months before she and her husband were due to make their first ever trip to Ireland, Robie received a call from Karen Hickey in response to one of her multitude of queries. She remembers being “just stunned” when Hickey identified herself as being in possession of the diaries.

With Hickey’s help, Robie managed to trace some Harshaw relatives on her trip to Ireland, and even tracked down James’ great-grandson, Hugh Harshaw, who lives in Poyntzpass, County Armagh.

“Hugh was just speechless when I told him I knew where the diaries were,” laughs Marjorie as she recalls that first meeting.

“He had worked the fields with his father Robert, and said that Robert always talked about his grandfather writing the diaries and wondered where they were and wished he could get them. Hugh has also kept a diary all his life. When I saw how he reacted to the news that the diaries still existed, I told him I would see what I could do to get them to him,” she said.

In early 1996, much as she herself had received the diaries, Hickey sent the remaining five volumes without warning to Robie. Figuring that Sally Lowing was the only person who could make the decision on where the diaries should end up, Robie tracked Lowing down, and told her she had found the Irish family descended from James the diarist.

“I told Sally that I felt the diaries were a valuable history of the community and belonged back in Ireland. I could look at those books and find the day my mother’s father was born in Ireland and discover what the weather was like that day.

“So I knew they were very important and needed to go back to Ireland, but didn’t know how to proceed. I figured that Belfast was closer to the community and the diary mentioned a lot of ancestors of people who still live there, so it would be better to send them there.”

Lowing agreed, and Robie’s next move was to contact the New England Historic and Genealogical Society which agreed to make microfilm copies of each of the volumes for safekeeping.

Once this was done, the society advised Robie to transcribe the manuscripts. She started in the spring of 1996 and worked all the way through the summer. Once the transcription was complete, she knew it was time to take them home.

In November of 1996, Marjorie packed the Harshaw diaries and prepared to bring them back to Ireland. She contacted the Office of Public Records in Belfast who said they would be delighted to showcase and preserve the diaries.

It was then discovered that the final volume of the diaries, spanning the years from 1864 to James’s death in 1867, had been in the possession of the Public Records Office for some years, and they had a copy on film. Finally, the complete set was restored to its entirety, and James’s story, including a moving account of his death written by his son Andrew, was returned to his descendants.

On this trip to Ireland, when Robie discovered there was no marker on the Harshaw grave, she urged her Irish and American cousins to join forces in raising the necessary funds.

In March of last year, James Harshaw was finally commemorated with a tombstone erected at his grave at the Glasgar Churchyard and several descendants from various Harshaw lines traveled from the U.S. and England to be at the dedication ceremony.

What is especially interesting about the Harshaw diaries is the family link to the famous Brontë clan. James’s oldest son Hugh was named for Hugh Brunty, the grandfather of the famous literary sisters who was hired by the diarist’s father to work the farm.

James Harshaw Sr., a Presbyterian, was fond of Hugh and helped to arrange his marriage to Catholic Alice McGlory, a match which would have gone against the prevailing wisdom of the times.

In another interesting sidebar, Harshaw’s sister Jane was married to a man called Samuel Martin. Their son John, James’ nephew, was one of the Young Irelanders, a group founded in 1842 to help promote the romantic nationalism which was sweeping much of mainland Europe at the time. Martin was arrested along with Young Irelanders, John Mitchel and Charles Gavan Duffy, and sentenced to ten years transportation.

His brother, who was in the court, was outraged and immediately challenged the jury foreman to a duel. He ended up receiving a sentence of his own, and was duly imprisoned for a month.

John Martin was sent to Van Diemens land and was then granted parole in 1855 but not allowed back to Ireland. He moved to Paris for a while, and managed the family business when eventually allowed back to Ireland. James also maintained a steadfast interest in his nephew’s well-being, and the diaries contain many references to communication between the two men.

Famine references also abound through- out the diaries, though Harshaw’s parish in Northern Ireland was not as severely hit as other parts of the country. Even still, emigration played its part, and Harshaw lost two sons to New York in 1849 (see excerpt).

Two things become immediately obvious during even a casual perusal of the Harshaw diaries. The first is that James was a man who had a light-hearted manner and he enjoyed conferring nicknames on his nearest and dearest. His wife Sarah was referred to throughout as “the Dandy,” son Samuel Alexander was “Absalom,” and Andrew became “the Chieftain.”

One also gets a sense of James’s unerring love and regard for his wife, ten children and extended family, especially in the moving passage he writes about his sister Jane’s death in July 1847 (see excerpt).

Although his spelling and grammar may not have been perfect, Harshaw proved himself diligent and intelligent, faithfully recording years of farm transactions, along with providing a valuable insight into life in Ireland in the 1800s.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September/October 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply