The historic connection between Black American civil rights activists and Irish nationalists.

Exactly 30 years ago this October, the Northern Ireland civil rights movement burst onto the international scene when television pictures showed marchers being batoned off the streets of Derry by the police.

Non-violent protests against discrimination had been percolating for years, but it was the small march in Derry that really launched the movement. When film showed the police using water canon against the marchers, commentators all over the world compared the scene to black civil rights marches in the U.S., an identification the marchers themselves were keen to encourage.

Like the black American activists, they demanded an end to gerrymandering, fair housing distribution and “One Man, One Vote,” and sang “We Shall Overcome” at rallies, sitins and marches across Northern Ireland.

They called themselves Ulster’s White Negroes, and drew on the historic connection between black American civil rights activists and Irish nationalists.

The links went back for several centuries. In the mid-1600s, Oliver Cromwell’s English army invaded Ireland and banished many Irish to become slaves in the West Indies, where some worked side by side with black slaves in Caribbean sugar cane fields. In Bermuda in 1661 and Barbados in 1668 the Irish on the islands were suspected of collaborating with black slaves in planning insurrection against the British authorities. The small Caribbean island of Montserrat became particularly closely identified with Ireland, and a 1780 book recorded that the vast majority of the inhabitants were either descendants of the original Irish settlers or natives of Ireland, “so that the use of the Irish language is preserved on the island, even among the Negroes.”

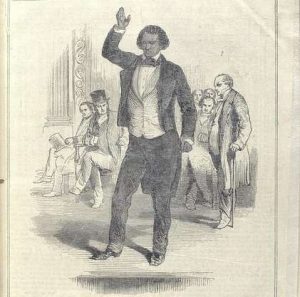

Ties were strengthened in the mid-Nineteenth Century, when Daniel O’Connell publicly condemned American slavery. In 1845, former slave Frederick Douglass toured Ireland to rouse support for the campaign to abolish slavery in America, and appeared with O’Connell at a political rally in Dublin’s Liberty Hall.

Douglass witnessed the destitution of many Irish peasants — his visit coincided with the first year of the Famine — and was struck by the similarities to Southern slaves.

After addressing a huge meeting in Cork, Douglass wrote: “Never did human faces tell a sadder tale. More than five thousand were assembled…these people lacked only a black skin and wooly hair to complete their likeness to the plantation negro. The open, uneducated mouth — the long gaunt arm — the badly formed foot and ankle — the shuffling gait…all reminded me of the plantation, and my own cruelly abused people.”

Throughout Douglass’s rise to the top levels of the U.S. Government — eventually becoming Minister to Haiti — he vigorously championed Irish independence, calling for an end to British rule, and hosting receptions in Washington D.C. for visiting Irish MPs.

The black American-Irish connection was strengthened in the early years of this century by Marcus Garvey, the political grandfather of black nationalism, who modeled the organization of his Universal Negro Improvement Association on the structure of Sinn Féin. At the month-long UNIA rally at Madison Square Garden in August 1920, Garvey telegrammed Eamon de Valera in the name of 25,000 black delegates to formally recognize him as president of the Irish Republic, and that same year Garvey sent repeated messages of support to IRA hunger striker Terence MacSwiney.

By the early 1960s, the black American struggle was again providing inspiration and support for Irish activists. The fledgling anti-discrimination movements in Northern Ireland repeated the sit-in and marching tactics of Martin Luther King, and borrowed some of the more radical strategies of black student organizations.

Northern Ireland civil rights leaders like Michael Farrell carefully studied the black American movement, and in the tense months following the Derry march of October 5, 1968, deliberately copied its methods of exposing government violence.

Farrell was prominent in People’s Democracy, the student movement that had sprung up around Queen’s University, Belfast, in the days after the Derry march. He led a civil rights march from Belfast to Derry in January 1969 that was carefully modeled on the black civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery of 1965. “The Selma-Montgomery march forced the federal government to intervene in Alabama…the local law enforcement agency was completely biased against blacks, and you could not achieve any sort of justice within the legal institutional or political structures within Alabama, so they staged a dramatic march across Alabama which was attacked by white racists,” argued Farrell.

The Belfast-Derry march turned out to be no less dramatic. The young protestors sang “On To Selma” as they walked, in conscious imitation of black American marchers. They were violently attacked by hundreds of counter-demonstrators at Burntollet and (like in Alabama) the local police refused to protect the civil rights demonstrators.

The police inaction at Burntollet made comparisons with Alabama all the more obvious, and undermined the credibility of the Northern Ireland government — precisely the result Farrell had been hoping for.

Links between the student protestors in Northern Ireland and the radical elements of the American movement were cemented later that year when Eilis McDermott of People’s Democracy visited Black Panther headquarters

in New York and was made an “honorary Panther.”

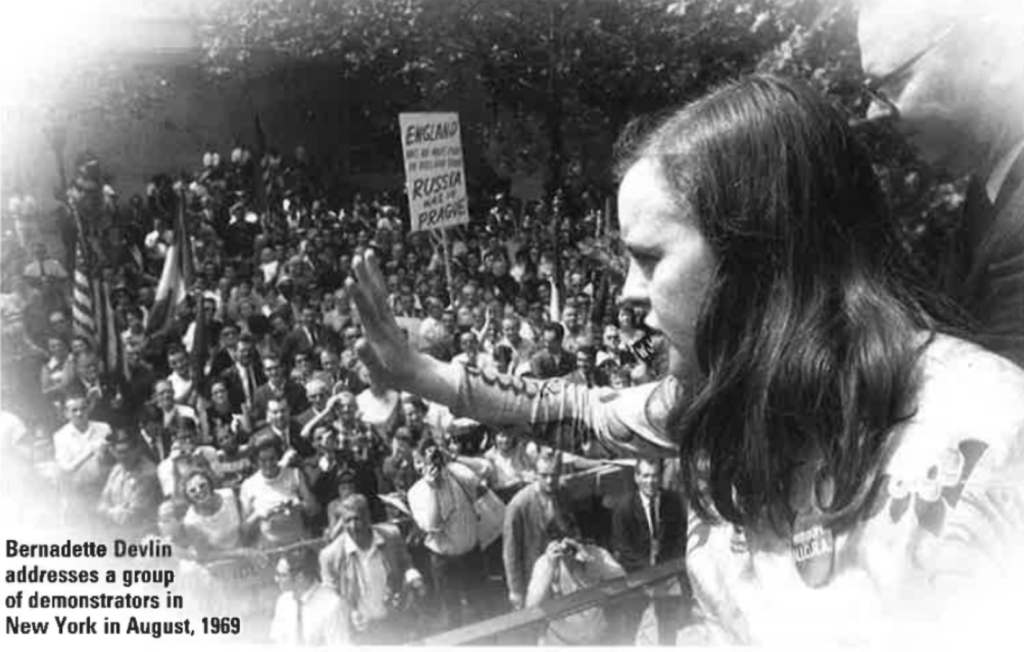

Ninteen Sixty Nine also saw Bernadette Devlin’s first visit to the U.S. Spirited out of Derry as British troops arrived to end the Battle of the Bogside in August, she arrived in America to give an eyewitness account of the fighting between police and Catholic residents of the Bogside, and to raise money for the civil rights effort in Northern Ireland.

Devlin [later Bernadette McAliskey] was a 22-year-old student at Queen’s in Belfast, the most prominent activist in People’s Democracy, and had been elected to the British parliament for the mid-Ulster constituency in April 1969 on a civil rights platform.

An undeniably articulate and engaging personality, Devlin became an instant hit with the U.S. media, appeared on major TV shows across the country, and won a wider audience for the Northern Ireland civil rights campaign than all previous visiting spokes-people combined.

Apart from speaking at the usual round of Irish American clubs and political meetings, Devlin also visited Operation Bootstrap in Watts, the black district of Los Angeles torn apart by riots a few years earlier. Devlin disturbed many of her Irish American hosts by pointedly reminding them that if they supported civil rights in Ireland, they should also support them in the U.S.

Four days into the trip, she astonished an Irish American rally in Philadelphia when she sang — even danced — with a black man, and asked him to sing “We Shall Overcome” to the audience. When presented with the keys of New York City by Mayor John Lindsay, she promptly had them turned over to the local Black Panther Party as a gesture of support for their efforts. Her vocal criticism of Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s handling of New Left protests at the Democratic Convention the previous summer alarmed many Irish Americans, and her popularity in conservative circles rapidly dwindled.

“Those who were supposed to be `my people,’ the Irish Americans who knew about English misrule and the Famine and supported the civil rights movement at home…looked and sounded to me like Orangemen. They said exactly the same things about blacks that the Loyalists said about us at home,” she said.

In Detroit she admonished Irish Americans for refusing “to stand shoulder to shoulder with their fellow black Americans,” and the trip ended in confusion when Devlin became increasingly suspicious that the funds she was raising were to be used to buy guns. She had specifically told audiences that she did not want the money for guns, but had overheard an organizer of her trip suggesting that the dollars might be diverted for arms anyway. Devlin cut short her trip, refusing to go to Boston or Washington D.C. to ask people for money when she could not guarantee how it might be used.

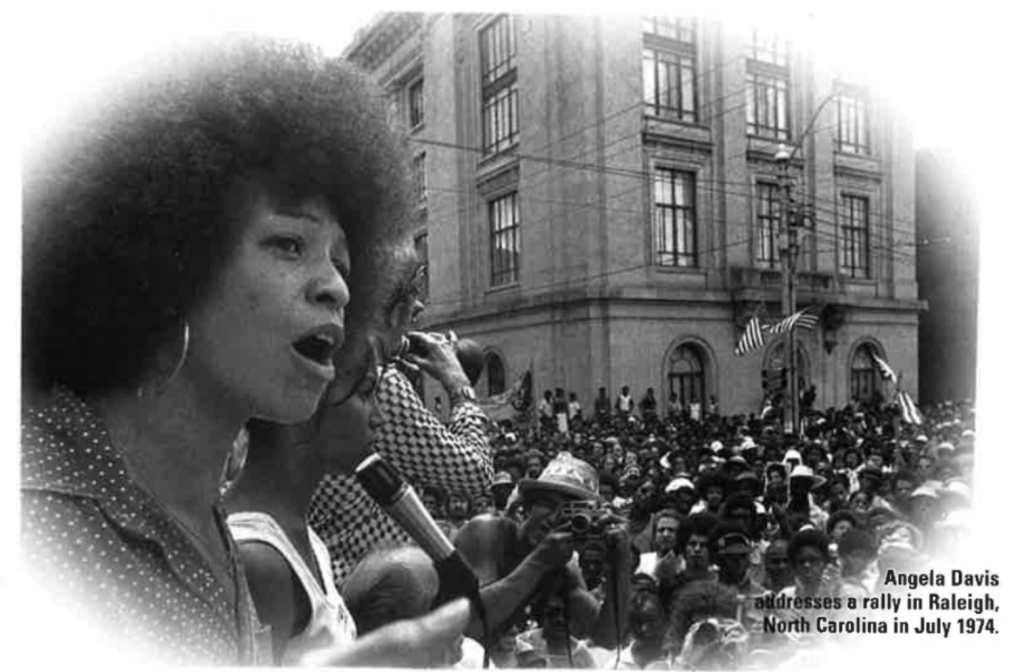

She returned to the U.S. in February 1971, and the conservative Irish Americans who now stayed away from her appearances were being replaced by black Americans as word spread of her interest in the civil rights struggle in the U.S. During the trip she met prominent radical black leaders like Huey P. Newton and Stokeley Carmichael and — despite strenuous objections from the local Irish-American community in San Francisco — even visited Angela Davis in prison.

Davis had been on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted” list, been publicly identified by President Richard Nixon as a “terrorist” and was awaiting trail for murder and kidnaping when Devlin visited her. “Angela Davis and I are involved in the same struggle…for the liberation of our own people,” said Devlin after the visit. (Davis was acquitted of all charges.)

Devlin confronted Irish Americans with the ambiguity of supporting civil rights on one side of the Atlantic and not the other. Daniel O’Connell had done the same over a century before, when he unsuccessfully urged Irish America to join the anti-slavery movement. Both O’Connell and Devlin saw their political and financial support in America collapse when they attacked Irish Americans for not supporting civil rights for black Americans.

O’Connell was attacked by the Tyrone-born Archbishop of New York, John Hughes, for his opposition to slavery, condemned by Irish American newspapers like the Boston Pilot and cut off from donations from various Repeal Associations across the country. The Repeal Associations had funded O’Connell’s efforts to have the British Act of Union repealed, but his call for Irish Americans to join the abolitionist movement caused disarray in the network of Repeal Associations, and those in Charleston and Natchez broke up in protest at O’Connell’s anti-slavery position.

Relations between Irish Americans and black have been complicated and, at times, even violent. In the mid-1800s, newly-arrived Irish immigrants often competed with freed black Americans for jobs, and the two groups

shared a similar social status. American employers in the middle of the Nineteenth Century often had their pick of Irish or black labor. In his study of the American slave system in the 1850s, Frederick Law Olmsted recorded that some preferred Irish workers, others black.

One Virginia landowner claimed Irish workers would perform over 50 per cent more work in a day than black slaves; another tobacco farmer from the same state explained to Olmsted that he employed Irish laborers over blacks not because they were more productive (“he thought a negro could do twice as much work, in a day, as an Irishman”) but because the work could be dangerous, and “a negro’s life is too valuable to be risked at it. If a negro dies, it’s a considerable loss, you know,” Olmsted was told.

Whatever their relative merits, black and Irish workers were commonly regarded as comprising the lowest social strata of American society. An English historian visiting the U.S. wrote home in 1881: “This would be a grand land if only every Irishman would kill a Negro, and be hanged for it. I find this sentiment generally approved — sometimes with the qualification that they want Irish and Negroes for servants, not being able to get any other.”

The sense of persecution shared by black Americans and Irish immigrants did not always lead to solidarity between the two groups. Violence broke out in several north American cities as freed blacks competed with Irish laborers in the job market, and black Americans were famous for telling “Irish jokes” during the 1800s, as laughing at Irish immigrants was one of the few ways that black Americans could openly take revenge on whites. To make fun of white Americans was not acceptable, but to join in the laughter at the Irish was. In 1876 one writer noted that black stevedores working in Cincinnati “can mimic the Irish accent to a degree of perfection which an American, Englishman or German could not hope to acquire.”

The Irish featured in the jokes told by blacks are characterized by their stupidity and laziness. One told of an Irishman who bought a gun and immediately killed his friend by trying to shoot the grasshopper on his chest, another of the Irishman who bought a water-melon and only ate the rind.

During the Twentieth Century, the perception of Irish American hostility towards blacks has often been rooted more in reputation than fact, although the Clann Na Gael branch in Philadelphia only agreed to carry a civil rights banner during the 1969 St. Patrick’s Day parade on condition it clearly supported civil rights in Northern Ireland, not black civil rights in the U.S., and the chant of “Niggers out of Boston, Brits out of Belfast” rang out from Irish Americans during the busing controversy of the early 1970s.

Other Irish Americans were more supportive of the black struggle. The late Paul O’Dwyer, for example, represented American blacks in civil rights cases and was involved with black political campaigns in Mississippi. O’Dwyer also wrote for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People magazine Crisis, and suggested that blacks should concentrate on highlighting the positive contribution made by their culture on American society, as the Irish had done.

Prominent ’60’s student radical Tom Hayden traced his Irish roots back to County Monaghan, and for much of the mid-1960s organized a black community union in Newark. (Now a California state senator, he spent much of July 1998 with the residents of the Garvaghy Road, waiting to see if the controversial Orange Order march would take place).

An Irish priest, Fr. Eugene Boyle, was the first person to open his doors to the Black Panthers’ free breakfast program in San Francisco when it began in 1969. According to the Black Panther newspaper, Boyle allowed his Sacred Heart parish facilities to be used by the Panthers for the program despite being “subjected to police intimidation and racist epithets and slurs, some even calling him a nigger-lover.'” Boyle also allowed the Sacred Heart Church to be used for Panther memorial services and even Panther political meetings. In May 1971, he flew from California to New Haven, Connecticut to appear as a witness for Panther leader Bobby Seale, who was being tried for murder.

More famous figures like the Kennedys also identified themselves with the struggle for civil rights in the U.S., and proved very popular with black voters. Despite being physically assaulted by some of his Irish American constituents in Boston for his support of busing in 1975, Ted Kennedy has remained an unswerving advocate of black civil rights.

Robert Kennedy was particularly identified with the black struggle during his years as Senator for New York (1965-1968), and proved a remarkably popular candidate with black voters during his presidential election campaign in 1968. He set up a ghetto renewal scheme in the Bedford Stuyvesant ghetto of New York, continually gave financial support to militant black leader Floyd McKissick, and was one of the first major American (or foreign) politician to go to South Africa to attack apartheid.

When he landed in New York after the South Africa trip in 1966, he pointed out the similar reactions to American blacks and Irish Americans in the U.S. “Everything that is now being said about the Negro was said about the Irish Catholics. They were useless, they were worthless, they couldn’t learn anything. Why did they have to settle here? Why don’t we see if we can’t get boats and send them back to Ireland?” he said.

Whatever the attitudes of Irish Americans to the black civil rights movement, activists in Northern Ireland benefitted enormously from its example and direct support.

Two weeks after Bloody Sunday in January 1972 — when 14 unarmed civilians were shot dead by the British Army during a civil rights march in Derry — the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, founded by Martin Luther King, despatched senior officials to Belfast to take part in protest marches and to speak at a Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) meeting.

Bernard Lee, a veteran of the Atlanta sitins and a close associate of Martin Luther King, was part of the group which included Juanita Abernathy, wife of Rev. Ralph Abernathy, another key King confidant. Juanita Abernathy told the NICRA conference that “the struggle for Irish freedom is the same struggle as that going on in the United States.”

Since then, many other prominent black American leaders have made political visits to Northern Ireland. Angela Davis was reunited with Bernadette McAliskey in 1994 when she visited Belfast to take part in a local women’s political conference. The military presence in Northern Ireland, Davis said, reminded her of apartheid South Africa.

Donald Payne, the first black American to be elected to the U.S. Congress from New Jersey, noted during his trip in 1995 that “What I have heard and seen here about the discrimination of Catholics is the same kind of thing that I see at home. High unemployment rates, high school drop-out rates and the sense of alienation from and resentment towards the authorities.” In 1997, Payne introduced a bill in the U.S. Congress to ban the RUC from using plastic bullets.

Such actions have helped intensify the identification between Nationalists in Northern Ireland with black Americans. SDLP leader John Hume is among those who quote enthusiastically and liberally from Martin Luther King, and his party still sings “We Shall Overcome” at its annual conferences.

Bernadette Devlin McAliskey has become something of a legend in black political circles, and has been a frequent visitor to the U.S. since 1969 and a regular speaker at black political gatherings, highlighting the cause of both Irish Republican and black American prisoners. In 1996 she spoke at fundraisers for the black churches destroyed by racist arson attacks across the American South.

In 1997, several prominent black Americans joined the campaign for the release of Roisin McAliskey, Bernadette’s daughter, from jail in Britain.

Roisin McAliskey was pregnant when arrested in November 1996, spent 15 months in various British prisons awaiting extradition to Germany on a bombing charge, and gave birth to a girl under harsh security conditions in May 1997.

New York’s first black Mayor, David Dinkins, addressed a meeting in the city protesting Roisin’s treatment, and a still radical Angela Davis spoke at a rally in San Francisco, attacking the “terrible mistreatment of Roisin McAliskey by her British captors…Roisin must be freed and Northern Ireland released from the shackles of British imperialism!” Roisin McAliskey was released in March 1998.

The recent ties have also helped Irish nationalists to more easily contextualize their political situation. During the recent clash over the proposed Orange march through Garvaghy Road, the international press often described Loyalist protestors as akin to the Ku Klux Klan, and the image of Northern Ireland Catholics as White Negroes still resonates in much of the media.

It is a useful image for Nationalist politicians in Northern Ireland, eager for the credibility of close association with the black civil rights movement.

When Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams visited the U.S. in September 1994, he made time in his hectic schedule to visit Rosa Parks, the woman whose refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus in 1955 sparked the historic bus boycott and catapulted Martin Luther King to the leadership of civil rights movement. (The boycott was itself an Irish form of protest initiated by Mayo laborers in 1880 who refused to harvest the crops of the notorious land agent Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott.)

Adams told Rosa Parks he had sung “We Shall Overcome” at the early civil rights marches in Belfast, and had been inspired by her principled and courageous stand. A few days later, Adams was hoping President Clinton would ignore British government protests and invite him to the White House.

Reminded of Parks’ refusal to be classed as a second-class citizen 40 years before, Adams told the intermediary between himself and the White House that he wanted an invitation, that he “would not accept a place at the back of the bus.”

Adopting the vocabulary and tactics from each other’s movements, and identifying with each other’s struggle, is a deeply rooted tradition in both Irish and black American political culture, and has proved crucially important in Northern Ireland over the last 30 years.

Editor’s Note: Brian Dooley is the author of Black and Green: The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland and Black America. (Pluto Press 1998.)

This article was originally published in the September/October 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

This is a good reminder of the similar struggles between two groups of people who have much more in common but who have also been baited by outside influences to compete against each other. The pie has always been big enough for all and I find it shocking that in this present day prejudices still exist and are also extended to the Palestinian people who are being decimated. There is definitely more sympathy in Ireland than here in the USA where our own rights are being eroded daily.