The most important American sculptor of the late 19th and early 20th century was born in Ireland.

If there was such a thing as an American Renaissance, Augustus Saint-Gaudens embodied it in sculpture. To Saint-Gaudens, an artist is an interpreter of beauty in the world. A work of art is the artist’s vision of a subject, colored by the light of imagination and expressed in symbols that convey what he or she has seen, in terms that will make others see believe, and revel in the vision.

A pioneer in moving sculpture from carved stone to cast bronze, Saint-Gaudens completed more than 150 commissions. Between his professional flowering in the 1880s and his death in 1907, this individual provided dramatic evidence that America can produce world-class art. “Aspect,” the Saint-Gaudenses’ family home in New Hampshire, is the only national historic site in America devoted to a visual artist.

From his mixed French and Irish blood, Saint-Gaudens may have derived that mingling of the Latin sense of form with a Celtic depth of sentiment that so characterized him.

In 1888 the sculptor told a correspondent “My name should be spelt without a hyphen.” Notwithstanding that assertion, the name still appears in many reference works as `Saint-Gaudens.’

His father was born in the village of Aspect, in the Pyrenees. His forebears on his paternal side were shoemakers. At an early age, the father, together with his family, left the native village and moved to the town of Salies du Salat. From there they moved to Carcassonne, where the father learned the trade of shoemaker from an elder brother.

The father eventually left home, ending up, by 1841, in Dublin. There he made shoes, which he sold to Dublin shops. At one such shop, he met a girl who was sewing bindings on slippers. She was the most beautiful girl in the world, he said then, and he continued to say it until the day he died.

Mary McGuinness came from County Longford. She had, Augustus tells us in his Reminiscences, “wavy black hair and the typical long, generous, loving Irish face.” Of her ancestry, Augustus knew nothing, except that her mother was married twice, the second time to a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars.

After marrying, Bernard and Mary Saint-Gaudens found rooms in a Georgian brick house on Charlemount Street in the southeastern section of Dublin. Two boys died in infancy before Augustus was born on March 1, 1848. At the time of his birth, the Potato Famine was in its third year. While the Saint-Gaudenses did not appear to suffer greatly, the situation undoubtedly was depressing. Consequently, the family sailed for America when Augustus was six months old. Bernard Saint-Gaudens quickly concluded that Boston was no place for a Frenach-born shoemaker. He journeyed to New York, there advertising his wares as “French Ladies Boots and Shoes,” and was followed by his family.

Augustus began to draw as a youngster, but his drawings were not remarkable. The only thing that made them noteworthy at all was that they coupled persistence with abundant energy. Those qualities drove the boy to seek an apprenticeship with a man named Avet, one of America’s first stone cameo cutters.

Eventually falling out with Avet, Saint-Gaudens went to work for another carver. Since his evenings were free, he also attended classes at the National Academy of Design.

At age 19, Saint-Gaudens traveled to Europe to continue his education. After arriving in Paris, he began studying at the studio of Jouffroy in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. It quickly became evident that Saint-Gaudens’ latent genius was for sculptural modeling: the buildup, lump by lump, pinch and pinch, of complex volumes out of clay or wax, later to be cast in bronze.

The time of Saint-Gaudens’ sojourn in Paris was one of great importance in the development of modern sculpture. Although Jouffroy was not a sculptor of the highest rank, his studio nonetheless was a center for what was then a new movement in French sculpture. The essence of that movement was the use of Italian Renaissance sculpture as an inspirational source.

During the Franco-Prussian War, Paris ceased to be a place for the serious study of art; consequently, Saint-Gaudens traveled to Rome. While there he met a partially deaf young woman named Augusta Homer, a sometime artist (and first cousin of the artist Winslow Homer), for whom Saint-Gaudens made the last of his cameos as an engagement ring.

After returning to America, Saint-Gaudens rented a studio in New York City. Soon thereafter he received his first commission for an important public work: the Farragut Statue in Madison Square Garden.

No work by Saint-Gaudens better personifies elegance and grace than his Diana. He had long wished to create an ideal female figure. The opportunity to make the weather vane to top Madison Square Garden allowed him to gratify that desire.

Davida Johnson Clark posed for the original Diana. Long before Saint Gaudens met Davida, he had been searching for her. His dream of fair women never varied. His own mother the long, beautiful Irish face established the ideal.

The Shaw Memorial on Boston Common represents a different kind of public sculpture. Considered by many to be Saint-Gaudens’ masterpiece, this Civil War monument commemorates Col. Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a black regiment that he commanded. Shaw and many of his men died in an assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina in 1863. After the Civil War, historian Henry Adams commissioned Saint-Gaudens to design a bronze statue in memory of his wife, who had committed suicide. the historian gave the sculptor only general instructions concerning what he wanted. “The whole meaning and feeling of the figure is to be found in its universality and anonymity,” Adams wrote.

In the Adams Memorial, which resides in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C., Saint-Gaudens’ imaginative powers reached their apex. The figure has been given many names; her creator gave her none. The meaning is a mystery; an eternal enigma. Saint-Gaudens’ General Sherman Monument was unveiled in New York City’s Grand Army Plaza in 1903. For a model, the sculptor used a famous horse named Ontario. For his principal, he used Gen. Sherman himself but complained that since the general insisted on looking at him straight in the eye, he could never get a good profile.

When dedicated, the monument was compared with earlier equestrian statues, including Donatello’s Gattamelata in Padua, and Andrea del Verrocchio’s Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice. As a result, Saint-Gaudens was accorded a place in the pantheon of world-renowned sculptors.

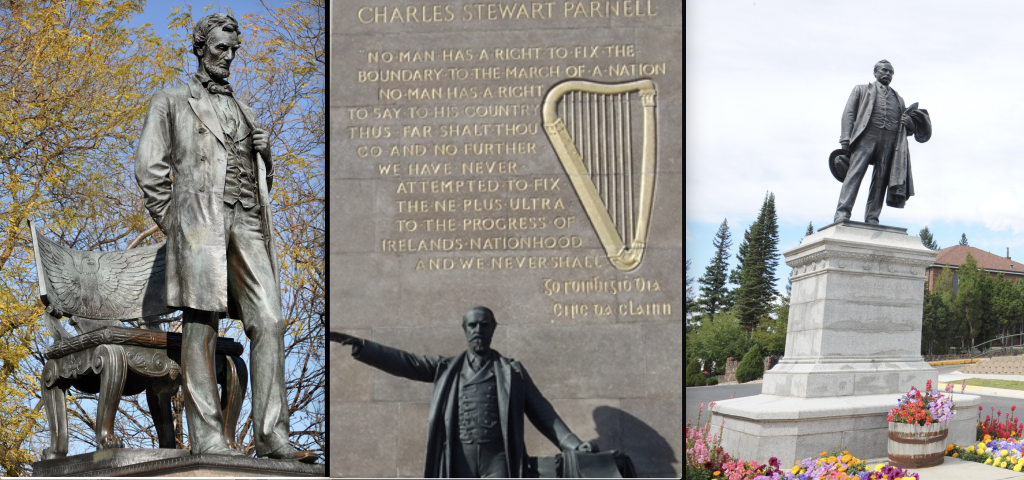

Flashes of “Irishness” were often observed in Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Biographer Burke Wilkinson says he possessed an openness and desire to please others that are more characteristic of the Irish than the French. In honor of his Irish mother and the place of his birth, Gaudens hoped to make the statue of the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell his finest. However, while working on the statue Gaudens was sick with the cancer that would kill him, and the finished work, which can be seen in the city of Dublin, is not considered to be his “finest.”

No one, however, will dispute the beauty of the American coinage that the sculptor designed. When President Theodore Roosevelt commissioned Gaudens to design a coinage “worthy of a great civilized nation,” Saint-Gaudens used as his model a shy 24-year-old Irish immigrant girl, Mary Cunningham. Her face became the face of “Liberty” on American coins, including the $20 gold piece. Saint-Gaudens died in 1907 before he was able to complete the finished design for the one-cent coin.

He died as he had lived, a member of no church, but a person of lofty character. his cancer-ridden body was cremated and his ashes deposited in the cemetery at Windsor, Vermont, across the river from his home.

By age 37, Saint-Gaudens had come to realize that there was an appealing world beyond the confines of the city; he therefore began searching for a summer home in the country. He found it in the area around Cornish, New Hampshire – hill after hill sweeping back from the Connecticut River to Vermont’s majestic Mount Ascutney.

In 1885, Saint-Gaudens, his wife, and several assistants rented an 18th-century brick tavern that had originally been called Huggins’ Folly. They came on the invitation of Charles Beaman, their lawyer and friend, who had purchased the inn the year before.

Saint-Gaudens found the place well-suited for the creation of sculpture. He eventually purchased the property from Beaman and changed the name to Aspet, after his father’s birthplace.

In July of 1900, the sculptor set up a studio on the property. He also lavished attention on the grounds. After the studio burned in 1904, Saint-Gaudens had a new one built, which became known as the Big Studio, also known as the Studio of the Caryatids. In time, the area attracted other artists, including poets, painters, playwrights, and musicians.

Soon after Saint-Gaudens’ death, the public began visiting Aspet. By 1919, family and friends had established the Saint-Gaudens Memorial. Its charter from the State of New Hampshire expresses its purpose: to aid, encourage, and assist in the education of young sculptors, and to encourage the art and appreciation of sculpture.

In 1964, Congress authorized the National Park Service to accept the property as a gift. Today, Aspet is officially known as the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site. It is unique among National Park Service properties in that it comprises both an art museum and a historic home, replete with original furnishings.

The Site includes the sculptor’s home, the studios where he worked, gardens, an extensive collection of artwork, and surrounding woodlands. Visitor activities include taking guided tours, viewing Saint-Gaudens’ artworks on exhibit, attending concerts and art exhibitions in the summer, as well as snowshoeing and cross-country skiing on the grounds in winter.

Begin your visit by viewing the introductory audio-visual program, then join a house tour. Inside Aspet, the original Saint-Gaudens furnishings reflect the character and taste of the man.

Visitors exit the house onto a spacious porch and proceed down a short flight of steps to the garden. A beautiful assortment of flowering perennials similar to the ones Saint-Gaudens planted makes the gardens at Aspet an attraction in themselves.

Saint-Gaudens is best known for his outdoor monuments, and Aspect has copies of two of the most well-received. A bronze reproduction of the Adams Memorial sits a short distance from the Little Studio. Nearby is a plaster reproduction of the Shaw Memorial. What makes this piece so riveting is its blend of the real with the symbolic. Individual soldiers – from their finely chiseled faces to their packs and rifles – are so lifelike that each could stand alone as a portrait.

Each summer, exhibits are mounted in the gallery on the grounds. They vary in subject matter from retrospectives of Saint Gaudens’ works to the works of contemporary artists. From mid-June to mid-August concerts are held at the Site on Sunday afternoons.

The opportunity to view one artist’s work in an ambiance of distant mountains, formal gardens, and unhurried quiet is infrequently encountered. The Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site is a tribute to one of this nation’s cultural giants.

The magic of Aspet lies in the way it brings to life an important personality. From the furniture Saint-Gaudens sat on, to the studio where he worked, to the brook he sometimes swam in – all of it can be seen and experienced so that a visit here provides a rare opportunity to savor the context in which the sculptor lived and worked.

The National Historic Site is located just off State Rte. 12A in Cornish. From I-89, take exit 20. From I-91, use exit 8 if northbound; exit 9 if southbound.

The house, studio, and other structures are open from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily, Memorial Day through October. Visitors have year-round access to the grounds. For more information, visit the Saint-Gauden National Park Service webpage or call (603) 675-2175.

Leave a Reply