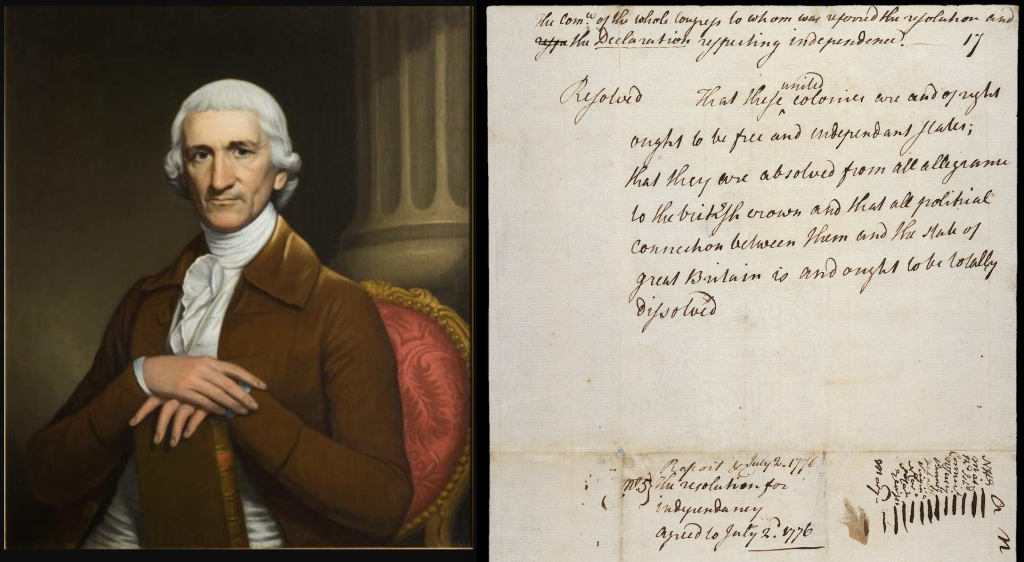

When Congress ordered the official reading of the Declaration of Independence, Irish-born Charles Thomson performed that duty on July 9, 1776, it was Irish-born Charles Thomson who called upon to organize the procedures for the election of the first president of the United States. The election over, Congress appointed Thomson as its representative to inform George Washington of the country’s choice.

For years, the Irish American community has been self-afflicted with a myopia that distorts its perception of traditional values.

As in Alzheimer’s disease, the condition is marked by an imperceptibly progressive forgetting of goals and a gradual decline into powerlessness. The final state is the death of a culture.

Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, the condition is reversible. Therapy is shockingly simple. It has to do with measuring and goal-setting.

The process assumes an awareness and ethnic perception of agreed-upon hierarchical values. One would think that Irish American values could be inferred from, for example, an analysis of the ritualistic choices of the Irish man/woman of the year.

Apparently not. A few choices appear to be based merely on personality cults, and a few others on the need for an organization to fund dinner tables.

Thankfully, many choices represent credible selections, but that doesn’t confront the problem. What is the goal? And what is the measure of attainment? “The rater rates the rater” is an old adage: Who confers honors reveals his own values.

A community honors itself by what it values. What it values, it becomes. The process is a push-and-pull mechanism by which the community identifies and cleanses itself. Goal-setting and measurement of attainment is the process.

Perhaps the discussion could be advanced by considering models who embody the values for which Irish Americans would choose to be respected.

In this bicentenary year (1987) of the American Constitution – when one can almost guarantee that its Irish associations will be overlooked – one such model for meditation could well be Derry-born Charles Thomson. (Have Derry societies honored him?)

Simply put, Charles Thomson was one of the 18th-century builders of this nation. Arriving here as an orphaned Irish boy, he made the most of his educational opportunities, becoming, in turn, a teacher, a prosperous businessman, and one of the key persons in the shaping of American independence.

A Presbyterian clergyman and fellow Irishman, Dr.Francis Alison, provided the lad with shelter and schooling. As a young man, Thomson, through his friendship with Benjamin Franklin, earned an appointment as a tutor at the Philadelphia Academy (later to evolve into the University of Pennsylvania).

Subsequently, he became the Master of the Latin School in the institution afterwards to acquire renown as the William Penn Charter School. While he was still in his 20s, his intellectual bent further showed itself in his participation in the founding of the American Philosophical Society. He later serves as its Secretary.

Before his 30th birthday, such was his reputation for justice in the community that area Indians petitioned him to register their rights according to the Treaty of Easton, later adopting him into the Delaware tribe with the name “Man Who Speaks Truth.”

About this time, he gave up teaching to try his hand at merchant trading. His rapid success in these ventures and the fairness of his business dealings enlarged his opportunities to influence the community. Steadfastly, openly, and fearlessly, in a city inclined toward conservatism, he espoused revolutionary ideas coming out of Boston.

His vision of freedom for the colonies was so fervent that he earned the sobriquet “The Life of the Cause of Liberty” from John Adams. It is no surprise that when the first Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774, Charles Thomson was its choice for Secretary.

Fortunately for U.S. history, Thomson was repeatedly elected to that post from 1774 to 1789. Only his records detail the birth pangs of the new nation.

Slowly, and not without opposition, the Congress came to support independence from Britain. With skillful diplomacy the Secretary’s private conversations guided doubters can only be inferred from the use of his position and the strength of his commitment to independence.

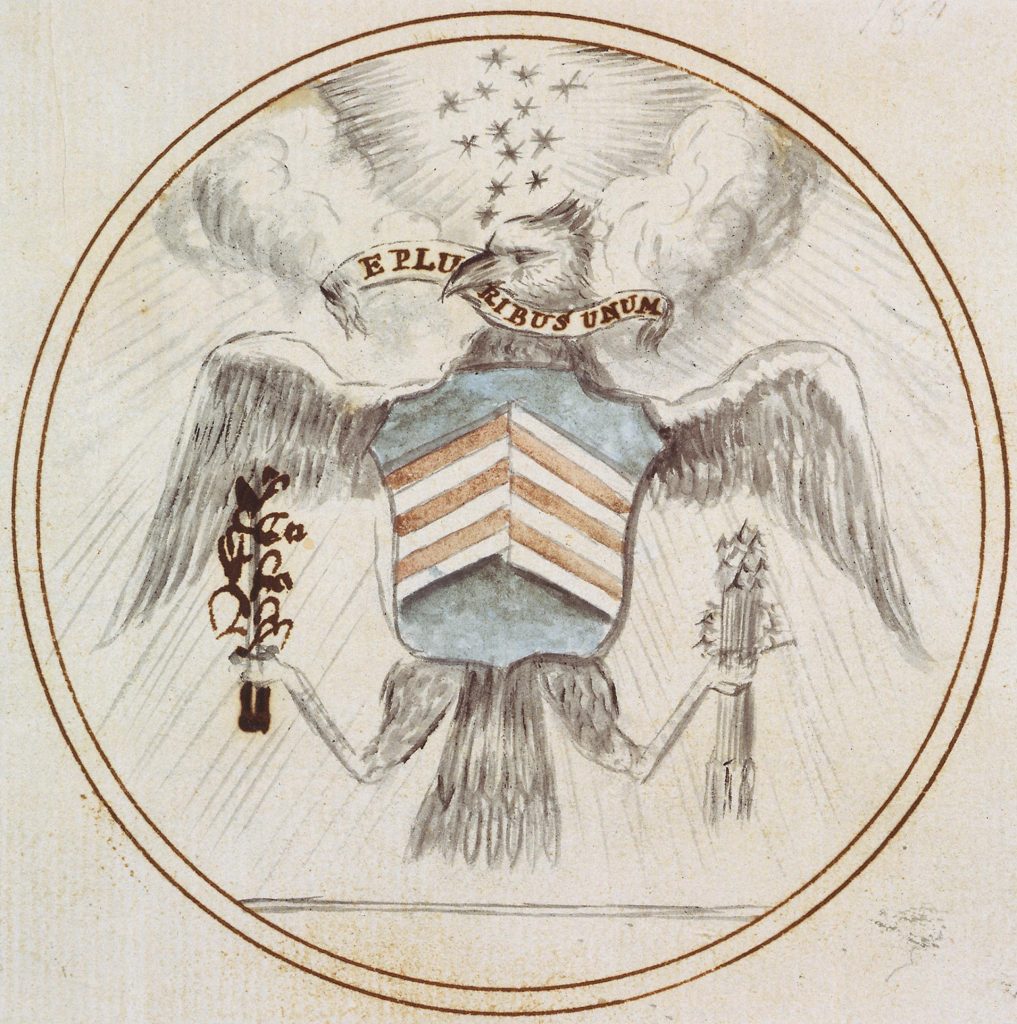

To Thomson, also assisted by William Barton, the country owes the design of the Great Seal of the U.S. – unchanged since Congress adopted his design on June 20, 1782. When Congress ordered the official reading of the Declaration of Independence, Irish-born Charles Thomson performed that duty on July 9, 1776.

Twelve years later, Charles Thomson was called upon to organize the procedures for the election of the first president of the United States. The election over, Congress appointed Thomson as its representative to inform George Washington of the country’s choice.

Then, at 60, resigning from an active life in service of his adopted country, Thomson focused on the more purely intellectual interests of his younger life.

Never having lost his skill in classical languages, he began a series of translations of the bible, resulting in 1808, the first English-language edition of the Septuagint, published in his 79th year. For six more years, he continued his biblical scholarship.

What is the measure of this man? A man of probity and integrity. Citizen par excellence. A man of thought, imagination, and action, dedicated to God and Country. A scholar. By his fruits, you know him. “The observed of all observers.”

What Irish Americans would not take this man for a model? Whom would he not inspire? If his virtues represent the goals of Irish Americans, who, measured in their attainment, would not be truly distinguished in the conferral of the Charles Thomson medal for excellence in citizenship, scholarship, and general probity? What an Irishman or Irishwoman of the Year would be there?

And what country — other than Ireland, of course — having given so great a son to the United States would fail to press the advantage such a relationship offers, particularly in this bicentennial year of the Constitution?

Note: This column was first published in Irish America in April 1987

Leave a Reply