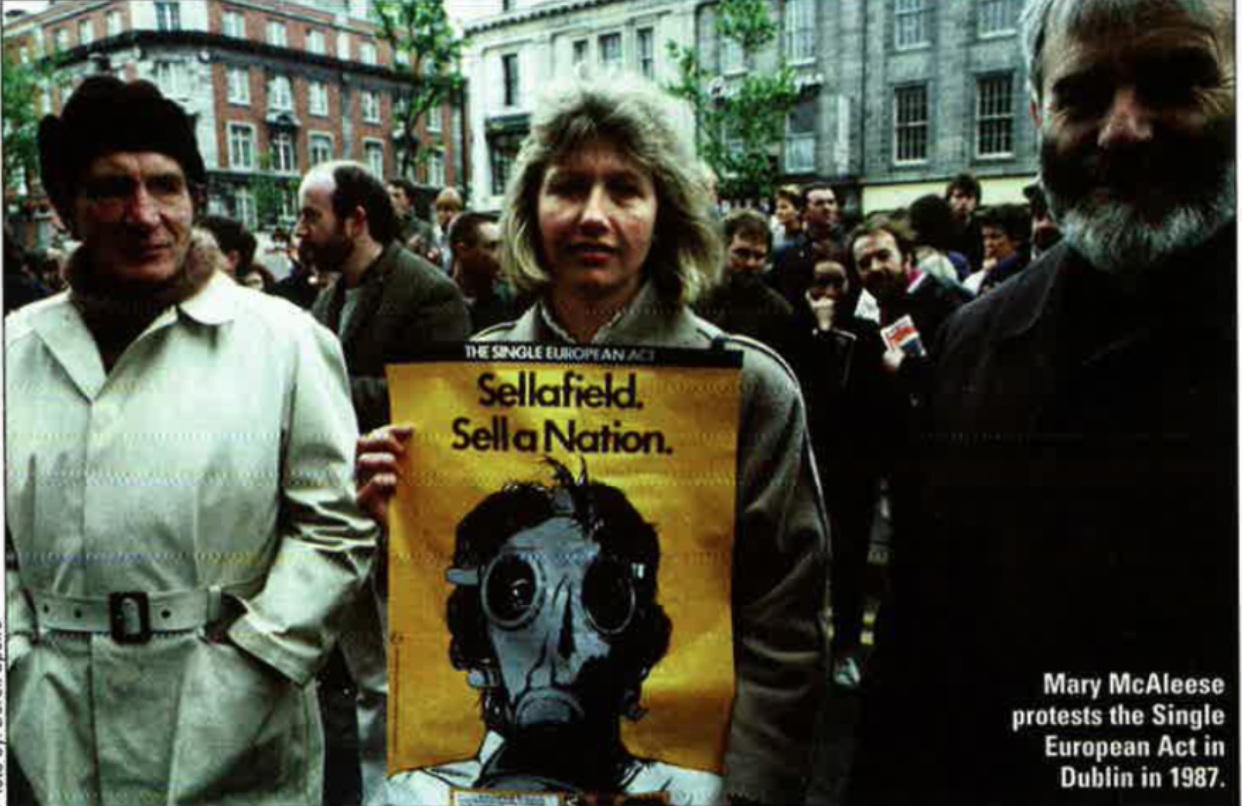

Mary McAleese was elected president of Ireland in October of 1997. It was an astonishing outcome. Just a few months previously, the 46-year-old law professor at Queens University in Belfast was hardly known in the Irish Republic and the notion that a Northerner could be elected president of Ireland seemed a farfetched one.

Then in one of the most stunning ascents to power in Irish history, McAleese defeated odds-on favorite former Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Albert Reynolds for the nomination of the Fianna Fail party, the largest in the nation.

She won out in a bitter presidential campaign against four other candidates, during which her Northern roots became the focus of the election race. This happened after leaked summaries of private conversations she had about the Northern situation with a Department of Foreign Affairs official from Dublin became public.

Despite that and a huge campaign against her in sections of the Irish media, the smearing tactic backfired in spectacular fashion and McAleese was easily elected to the highest constitutional office in Ireland, succeeding Mary Robinson.

Since taking office McAleese has adopted a more informal style than her predecessor, a fact very evident in our interview conducted at the presidential residence in the Phoenix Park. McAleese is an animated talker with a wry sense of humor and a relaxed style which puts people instantly at ease. It is an American-style trait which will stand her in good stead when she visits the U.S. in late June this year. We began our interview by speaking about President Clinton, a man she hopes to meet on her first presidential visit here.

Irish America: You met President Clinton during his visit to Northern Ireland in 1995. What were your impressions of him then and now?

On the day that he came to Northern Ireland, I don’t think there is any doubt that the Unionists, for instance, were very skeptical. And you know as well as I do the minefield that is Northern Ireland. If you use the word Derry instead of Londonderry, or Londonderry instead of Derry, everyone is exercised. The opportunities to make a mess are total. For a president to come, and speak off the cuff as he did was amazing. He spoke flawlessly. He did not put one single foot wrong. He didn’t get one inflection wrong, he didn’t get one name wrong. I was absolutely mesmerized by his sheer intellect — the man is incredibly clever.

I don’t know a politician on this planet who has the intellect, the depth, the charismatic skills of this man. He is extraordinary.

What he did that day was a miracle, because there was a lot of Unionist skepticism about him, a lot of determination that no matter how good this party got, they weren’t going to enjoy it. And yet they did. Over the twenty-four hour period, he effectively seduced them. He won them over.

He and his wife worked a miracle that day. I just want people to know how very grateful we are for this president who is so committed. He has been a large part of the scaffolding that is holding up this kind of precarious edifice of peace.

What are your own American influences?

Like everyone else on this island, many of my family are either in America or Canada, and there are quite a number of influences from there. But having been a teenager in the 1960s, I would have to say that the biggest influence on me was John Fitzgerald Kennedy. I have portraits of him in my study, and for all the attempts that have been made to debunk the myth, it was terribly and still is very real for me. On my first trip to Boston two years ago, I went, as a sort of pilgrimage, to the John F. Kennedy Library. I just stood and cried. I think that probably says something about the passion that I have for him and the vision that he had for the `60s, which I regard as the watershed generation. He had a strong sense of commitment to public service. I believe they [the Kennedys] never forgot where they came from. I hope that I never forget where I come from, and to whom this victory belongs and to whom I belong. It does not belong to me. It belongs to all those generations whose lives were lived in frustration, who prayed their way out of it. They were angry, bitter and resigned and far too stoic at times, but they kept hoping for a better world for their children. Well, this is it. People like me have had to make it. We are going to keep on making it.

I would be one of that generation who owes to John F. Kennedy the view that as a child of God, as a young Irish woman, no matter where I was in the world, no matter what forces raged against me, particularly those [forces] of psychological oppression that said you are a lesser person, that those elements were not worthy of anything but contempt. These were things that had to be overcome. Not just for your own sense of self worth, but in order to thank and redeem the effort of those generations that are gone past.

How do you see your role as president with regard to the Irish in America?

I see it as very important. I think our relationship with the Diaspora, or what I call the global Irish family, is vital and in some ways, defines us.

We are all familiar with the sorrow and loneliness of emigrants leaving for America, many of whom established good, modest, hardworking lives. Out of that modest existence, money was saved and sent back home to try and help put the seed corn into Irish education and economy. That investment has now paid off.

We are very grateful to the ongoing American commitment to Ireland in all its aspects because we are on the way to achieving phenomenal success. As a small island off the west of Europe, it is desperately important to us that we have friendships that open a window onto an entirely different world to ours. It helps us to blossom and grow. I want to be able to celebrate, and thank people for that and develop a sense of the global Irish family.

You don’t have to be born on the island of Ireland to be Irish, or to contribute to the building of the image of Ireland -to the good solid future of Ireland. So much of the work has been done elsewhere, much of it in Irish America. We’ve already gone to considerable lengths to ensure that those who are actively engaged in working for the Diaspora are very welcome here, that this is home for them too.

Irish Americans do feel that sense of homecoming when they visit for the first time. Writer Pete Hamill refers to the sense of it as “back to where I’ve never been.”

In a sense too, it is true also for those of us going to America, because so many of us have relations that live them. I know that when I visited Boston for the first time two years ago — I had been back and forth to the States, but had never been to Boston where I had a huge mount of family, including an elderly grand-aunt who went over as a housekeeper and became a very well- known, though not well-liked, property owner! I felt more than a little of what an Irish American might feel when they come to Ireland. It was a bit of what I felt in the John F. Kennedy Library. What was I crying for? What was I nostalgic about? All of that landscape somehow is part and parcel of my heart and soul, and when I got them, it was that instant recognition that part of me is there.

You’ve obviously thought about the different elements of Irish identity. Is that because of your own background?

My sense of identity was the energy behind my campaign. I was born in Belfast to a father from the west of Ireland, and a mother from Northern Ireland. I was born into the Nationalist tradition, but I played and grew up with members of the Protestant and Unionist traditions. We were in an area that was described as a mixed one. For quite a long time we were the only Catholic family on the street. But I grew up in an Irish tradition, with a very confident sense of myself being Irish.

I think the Irish Americans identify with that even more so perhaps than the people who live on this island without ever having to challenge or worry about their own sense of identity. Because when you live in an environment where you are accommodating yourself to another culture, and the people are asking you who you are, and what you are, you have to stop and think Well who am I? What are the characteristics that I have that are uniquely Irish? What is the history that has affected — or some might say, infected-my sense of being?

I grew up with that. I have never seen any straight lines in this place. When people try to slip things into itty bitty boxes and neat little phrases, I never understand, because I grew up in this extraordinarily complex world. When I hear people trying to identify West Belfast as Republican, I think of all those people I know there who are not one bit Republican. So people shouldn’t use these blanket terms because they are unhelpful and also grossly inaccurate.

Every contradiction that exists in modem Ireland was in our front parlor at some stage or another. I just didn’t recognize in those days quite what it was that I was growing up with, and more importantly, trying to make sense of, and trying to reconcile.

So your Northern background is vital to you?

Yes, it is intensely important to me. It is part and parcel of that pride and energy -that determination that I am Irish. I’ve never seen myself as anything else. I’ve known, obviously, over many many years, there are those who either wanted to ignore the Irishness of the Northerner, deny it absolutely, that it was less than real Irish. And I think it is important to challenge that. I’ve also known that that mindset is relatively small. But somehow it seems to have a profile publicly which I think its true strength does not justify.

I was always trying to point out to people, whether it was north or south of the border, who lived with those easy stereotypes, that life was more complex than that. Ultimately, what triumphed was my own view of the essential integrity of all it is to be Irish, of the acceptance of what it is to be Irish. For that reason, my own victory is all the more important.

You showed extraordinary confidence during a very rough campaign for the presidency. Where does that come from?

I’d like to think it was confidence rather than arrogance, because I think there is a major difference between the two. I keep reminding people, what matters a lot to me as the president of the Republic is that I’m the First Citizen of that Republic. What does that mean? I am a first among equals. People who are equal to each other. It is very very important to me that in everything I do and say, that I am capturing that sense of absolute and utter equality. That is one of the wonderful things about being the president of a Republic.

I’m part of that generation that is only one generation removed from the barefoot father who went to school in County Roscommon, who had great talent and good ambition, but his generation were never able to deal with those ambitions in the sense of giving life and expression to them because life dealt them a particular hand. And that hand came out of the history of this country.

That generation, my father’s generation, gave their children a strong view that this was the first generation that would help Ireland to really blossom. And here we are, at the end of the century, a nation absolutely in its stride, whose young people are highly educated, talented, sophisticated, energetic and creative. We have a roaring economy, which those who want to be skeptical would say is heavily dependent on European money. Absolutely not true. It is coming out of the investment that we made, and the people like my father made, in the education of their children.

You are clearly comfortable being identified as an Irish Nationalist from Northern Ireland.

Yes, I am a Nationalist. Yes, I am Irish. I am not a Unionist. I think it would be an insufferable insult to anybody to pretend that I am something that I am not. Now, that said, I think the Unionists respect you more for being absolutely up front.

The biggest problem on this island is the failure of Nationalist and Unionist to find a way of living together that sustains peace. It doesn’t mean that every Nationalist and Unionist has been at war with each other, they have not. But it does mean that we’ve lived through a long period of sustained instability, and that we haven’t been able to find the constitutional framework that allows everybody to enjoy utter confidence in the institutions.

I grew up in a mixed area in Belfast. My family were among the very few Catholic families living in this particular area. I grew up with Protestant friends. I learned to love them. I learned about their culture. Perhaps not enough, because we’re very good at masking in our discussions with each other what we truly think and what we truly feel. We’re not terribly good at revealing ourselves utterly to each other, and sometimes we think silence is a better way because it doesn’t provoke an angry response, and in some ways that thought has been insulting to each.

For that reason, we have lived side by side but with two separate versions of who we are and what we are — two separate identities, two separate sets of raw hurts and raw wounds, which we think the other has inflicted. We have sat in this hermetically sealed world, sealed off from each other, firmly convinced that we are victims and martyrs of each other, and each of us waiting for the other to apologize — a permanent standoff.

Are you hopeful about progress in the North?

I think we are at the edge right now. Everyone is lined up along this great chasm, and there is a very fine little bridge, and most people claim they are lined up to go over. That bridge is not a big solid structure. For some, it looks very shaky indeed. Everyone is jockeying for position not to be the one who goes over the bridge first. It is exactly as one might expect in this period when we have had, for the first time ever, the Unionist and Loyalist parties sitting down to talks attended by Sinn Féin and the SDLP [leading Nationalist parties].

We have the bones of the groups together now that are necessary to form a consensus. I think it is important that through all the trauma that we’ve endured with sectarian murders and killings of all kinds that we do not forget to acknowledge what is happening on the plus side. These talks, while they may look small from 3,000 miles away [U.S.], or from where I sit, are massive. These are very big advances.

This time, I’d like to think that people are aware of just how extraordinarily difficult it has been to get to where we are now. The pieces fall away very quickly. Governments that are interested can change. Governments that have majorities that can help the process can change. Interest from major politicians can grow cold.

All of those pieces that we have now — we have a marvelous opportunity, but it is not an opportunity of which the life span is guaranteed. I think that the ordinary people know that quite powerfully, and they want to maximize this opportunity. So you have the forces of good against evil.

I said in my inauguration speech that I was going to build bridges and I knew that it would entail sacrifices on my part, that I could not go around and will not go around telling other people to change their behavior if I’m also not prepared to change my own. I’m prepared to challenge my old baggage, my old bigotry, things that are deeply rooted inside of me, the kind of things that all of us need to address in Ireland and to address in the mirror first. I’m prepared to do that, and to be told if I need to do more of it.

President McAleese, thank you very much.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May / June 1998 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply