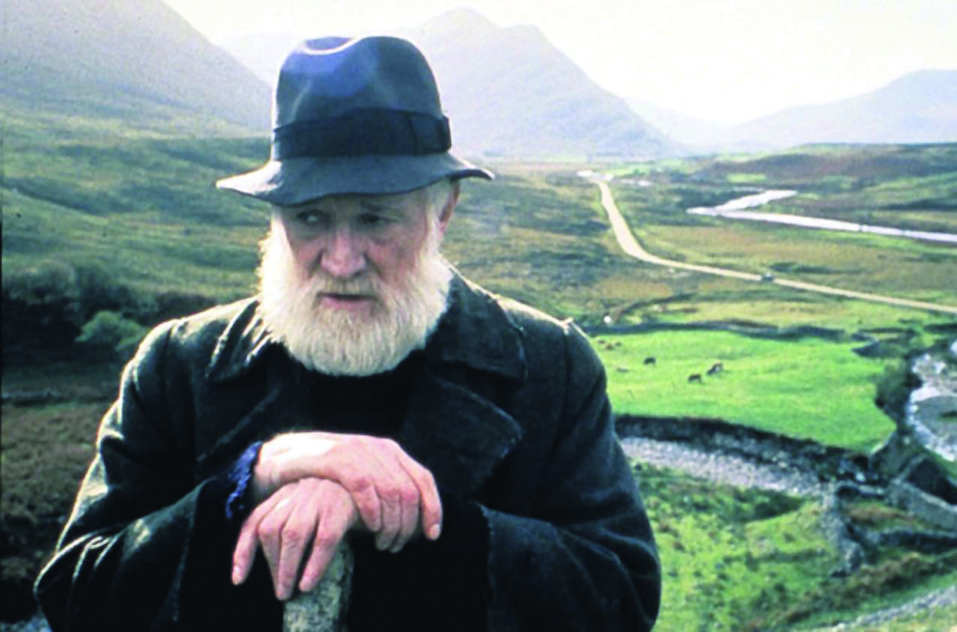

At 60 and after a career of 40-odd films, Rlchard Harris had spent most of the last decade out of sight and out of mind in the Bahamas. What has brought him back from a life of beachcombing is the lead role in The Field, the latest movie from the Jim Sheridan/Noel Pearson duo of Oscar-winning My Left Foot fame. He also had an acclaimed stint as Henry lV in London’s West End and The Evening Standard Award for Best Actor-given in past years to the likes of Gielgud and Olivier-was his for 1990. Now his performance as Bull McGabe in The Field has brought him a Golden Globe nomination and he is being touted by many as a sure bet for an Oscar nomination in 1991.

One would wear out the exclamation point trying to accurately punctuate a Richard Harris interview. Dressed in baggy grey sweats, he receives journalists twenty floors up at a swank Park Avenue hotel, He is gregarious and open: “Richard,” he introduces himself. He stretches out on a couch, then bounces up on the balls of his feet, and clenches his fist to help get a thought across. Only occasionally does he look tired-but then he looks very tired indeed.

Still, Richard Harris is back, and his retirement hasn’t tamed him one bit.

lrish America: Let me start with The Field. Had you seen John B. Keane’s play before you took the role in the film?

Harris: No. The funny thing about that is that I didn’t actually read the play until two weeks ago. But when I did read it I was happy that I had waited. Jim [Sheridan] added so many dimensions to it, it’s a whole new production

What were your first impressions of the role when you first read the screenplay?

Actually, I don’t know if you know this, but I wasn’t the first choice for Bull.

It was written for Ray McAnally originally. [McAnally died before filming began.]

That’s right, and I was up for the role of the priest. In fact, no one wanted me for the Bull, no one thought I was right for it. Granada, the financial people, didn’t want me, and Jim didn’t think it was for me either. But before all this, I was really retired from making films. I was washed up, forgotten…I can say it. Either I had retired or somebody had retired me, but no one was knocking down my door. I didn’t want to do any film, but Jim is so clever, a manipulator, is that the word I want? Yeah, a manipulator. He sent the screenplay to a hotel where he knew I was staying and called me and said, “The script’s downstairs. If you don’t want to read the whole thing, we’ve marked out your lines. Why don’t you give it a read?” [Laughs ] So I read it through that morning and called him back and said I would do it. It was magnificent.

What attracted you to the Bull?

He’s a great figure, a patriarch, a very strong man. He’s in a line with other Irish figures—men like Michael Collins, Eamon de Valera, and back to Cuchulainn and Brian Boru. But he’s not just that. There’s one scene with the widow after the auction [the widow, a neighbor of Bull’s, is trying to sell the field that he has cared for and covets]: as she’s walking away, something is thrown at her. Bull turns around and says “Who threw that?” [Harris says the line in an outraged whisper.] “We’ve never done that here, never.” And then when she’s leaving, he helps her into her carriage-and this is the thing – he tips his hat. It’s a tiny thing, but the chivalry of it. The chivalry! And would you believe it, they cut that from the film.

You mentioned Michael Collins. How do you feel about Kevin Costner’s project to do a film of his life?

I can’t really say, as I don’t know Kevin Costner. There’s a new book on Collins out that he should read, a brilliant one. I wish him luck with it, but I hope he gets the accent right.

Did anything in the screenplay of The Fleld echo your experiences growing up and living in Ireland?

No, not really. One of the things I’ve been telling people is that this is not a film about Ireland. It’s universal, the struggle for the land and for dignity goes on everywhere: it could be a film about Indians, Africans, or anyone.

There’s a scene that I wanted to ask you about. it’s where the Bull has killed the American, and he now begins to realize it. He stands the body up and is almost dancing with it. How did you approach that scene?

Ah, now that’s a powerful scene. PAAAUUUURRRFFULLL! [Harris laughs, and then there is a long pause. l Well, it was simple really. He’s remembering his dead child, Sheamie. Tadgh [the Bull’s second son asks him how long it’s been since Sheamie died, and he tells him.} And when he’s looking at the American, it’s as if he’s looking at his dead son. That scene was also cut from an early version of the film. But I went to Jim and said “Look, Jim, we have to have it.” Because that’s the first time Bull breaks in the film. When his wife tells him near the end, “Bull, don’t break,” we look back and say “Ah! That’s where it started.” Jim saw it was right and he put it back in. He’s very good that way if you’re right.

How was it to work with Jim Sheridan? Had you seen My Left Foot before doing this film?

I hadn’t seen it. I knew it was there and was being acclaimed, but when I decided to do this one, I didn’t want to go look at it and decide what kind of a director he was. As far as working with Jim, I’ll tell you what I told a journalist in London who asked me how I would rate him among the directors of the famous—that I’ve worked with. ‘I’d put him in the top three,’ I said. ‘Who would the other two be?’ he asked me. ‘I’ve forgotten,’ I said. But I’ll never forget Jim.

You know, it’s funny—when journalists come to a set, I never talk to them, and they say, ‘Oh, he’s being difficult.’ I’m not being difficult. I’m just not into it, d’ye understand? People have said to me that I was very intense on the set and with Jim, and I say, ‘All love affairs are intense.’ That’s what it was, absolutely, it was an obsession-we were obsessed with getting this thing right.

Do you think The Field portrays an lreland that is in the past or one that is still alive?

It’s alive. It’s the backbone of Ireland, the soul. Bull’s determination is what made the Irish survive 800 years of British occupation. I say ‘occupation’ because Ireland was never conquered, it was only occupied.

The Field isn’t Dublin, it isn’t Cork. Dublin is an English town. People say, ‘What lovely Georgian architecture.’ That’s King George! That’s not Ireland.

Moving on to Henry IV—and congratulations on the Evening Standard award- do you want to occupy the same kind of place in British theater as former Evening Standard winners like Gielgud and Olivier have occupied? I mean anchoring major Shakespearean productions and such.

I don’t know what you mean, really, because you always occupy your own place….I’ve always had a problem with bureaucratic authority so I don’t want to become part of a huge organization. And I can only do one major Shakespearean role a season. But I would love to do a MacBeth and then do my own interpretation of Julius Caesar, with Caesar as a small part. So I will definitely be returning to the stage.

What about films? Would you like to follow The Field with more film roles?

No, no. I say this may be my final film ever – not my final performance, just my final film. When I made This Sporting Life [Harris’ portrayal of a footballer which won him the Best Actor Award at Cannes.] I thought, ‘This is it. Now I’ll get more solid roles like this one.’ There were two or three offers, but then it was back to the adventure stuff. So I can’t say what will happen. Though since you mentioned This Sporting Life, I’ll say that I considered that at the time my Hamlet, and The Field I consider my Lear.

As to films, I don’t want to use this word I hate, I mean when I hear actors say,’ I just want to act in films with some integrity, I just want to vomit, but that’s really what I would be looking for.’

You mentioned before that you had been forgotten by the film and theatrical industry before The Field. Are you bitter about that?

No, not at all. Listen, I arrived in England when I was 21 with twenty-odd pounds in my pocket, no letters of introduction, and not knowing a soul. I mean, I knew no one. How could I be bitter? That would be ingratitude, great ingratitude. I look back and I know that I have accomplished something. People will know that I have been here.

That’s not just something I say with regard to my career. In relationships, that’s how I look at it as well. I have two ex-wives who are the greatest of friends to me now. I mean, we could look back and focus on the bad times – and there were bad times – and be bitter as hell. But that would be too negative. Why look at it that way?

And another thing is that no one was forcing me to make those bad movies. Orca the Whale I thought was going to be another Moby Dick. It had that potential. When I read it, it was all there: the beauty, the obsession. And when it came out, it was a piece of shit.

The actors in my generation who I came up with—Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole – when we came into films, all they were making were costume pictures. And they knew that they had to come to us because we were classically trained actors and we could do those roles. Now, if you’re trying to cast an actor to play a New York City cop, you’re not going to come looking for me. Because you know there are others out there who can play a cop better than me.

Though it’s funny—I’m making a comeback, and so is Peter O’Toole. It’s that determination I talked about, the stuff that’s in the Bull – it’s because we’re Irish.

They say, ‘You’re done, you’re finished.’ And we say, ‘It’s not over yet,’ and we fight back.

What about Irish films – do you see Irish cinema making a small comeback now?

There is no Irish film industry. They’ve stolen it away-Universal snapped up Jim Sheridan for a three-picture deal or whatever.

But some of those films are to be set in Ireland.

Yeah, but the profits won’t be coming back to Ireland. If we had put up the two million pounds it cost to make My Left Foot, we would have eight million pounds back in the kitty now. But everyone in Dublin wants to spend their money building office blocks and great big developments down on the docks.

Do you think the Irish Film Board should be revived?

Absolutely! Finance a few films, and encourage some of the talent that is there now. ♦

Leave a Reply