When I was a child, I suspected my Da’s sister Violet was a gypsy. Not that she was a real descendant of the wandering tribes of Egypt, but she looked like one. Her jet-black hair was always tied back in a tight bun, and she always wore blowsy flowered dresses, scandalous crimson lipstick and dangly earrings. Then while we were visiting one cold and blustery winter Sunday when I was twelve years old, my suspicions were confirmed.

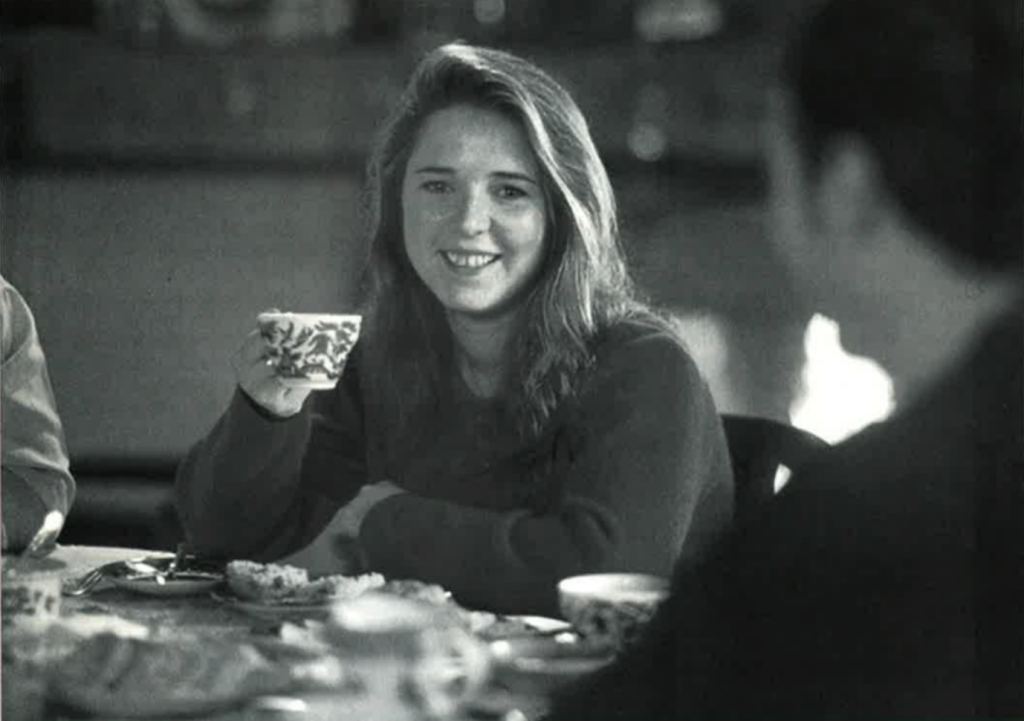

After serving us buttered toast and big cups of hot, sweet, milky tea, Aunt Violet swirled the dregs around in my china cup, dumped the last drops of liquid in the saucer, and read my tea leaves. The clumps of wet leaves just looked like soggy blobs to me, but for the next ten minutes or so Auntie Vi read them as if they were an open book of the future that would be my life.

Our family hails from Northern Ireland where there is a strong Scots influence, and in Scotland women who read tea leaves are called spae wives. The phrase entered the local lexicon via Viking raiders and is derived from the Old Norse word spa. It means “prophecy” and was used to denote people gifted with second sight, no great rarity among rural Celts even today — especially if one was born (as Auntie Vi was) on All Hallows Eve, the night when many believe that fairies walk the land.

The Chinese have been reading tea leaves to auger the future for thousands of years, and though no one knows how tea came to be brewed as a beverage, most scholars agree the practice probably originated in ancient China. According to legend, one day the emperor Shen Nung (27372697 B.C.) was preparing for a purification ceremony, and a tree leaf fell into his pot of boiling water. The aroma was so enticing that the emperor yielded to temptation and tasted the hot liquid. One sip was all it took. Shen Nung blessed the gods for having bestowed such a wondrous gift on him and immediately planted tea trees throughout his kingdom.

For three thousand years, tea was only known in Asia. By the seventeenth century, European explorers and traders had braved earth’s vast seas, visited most of its continents, and returned home with tales of strange new foods. In 1600, Queen Elizabeth I, who had heard many stories about tea, established the British East India Company to bring the fabled brew to England, but the Chinese considered the English barbarians and refused to trade with them.

The Portuguese and Dutch must have seemed more civilized because their trading efforts with China were successful. As tea flowed into the West, it became the subject of heated debate. A German physician, Simon Paulli, claimed tea drinking would hasten a person’s death, but a Dutch medical practitioner, Nikolas Dirx, insisted the new beverage was a life-sustaining substance.

When tea reached England in 1658, it was first sold at Thomas Garway’s, a drinking establishment that served another exotic imported brew-coffee. Garway extolled tea as a “most wholesome” beverage that would cure disease, reduce fevers, relieve pain, induce sweet dreams, and in general “make the Body active and lusty.”

With such recommendations, the English were won over to tea drinking in a trice, and within thirty years, the British East India Company had become the largest trading company in the world. Eventually, so much tea was being consumed that the government levied a tax on the commodity. That didn’t phase the people a bit. They continued drinking tea, and solved the tax problem by buying from smugglers.

In Ireland, tea was a privileged drink of the Anglo aristocracy.

Only small quantities of tea were accessible to the general population, and it was exorbitantly expensive. During the eighteenth century, most people could only afford to serve tea for special occasions. Families purchased a measure of tea leaves for the Christmas holidays and reserved half an ounce to brew another pot or two at Easter. Today’s ubiquitous custom of serving tea with toasted bread, sweet butter and jam was a luxury reserved for important visitors.

While the Irish had been drinking decoctions of many herbs for centuries, some people were puzzled what to do with the new dried leaves.

A story is told in Sligo, how one sailor brought a tin of tea home to his wife who proudly served plates of the dried leaves when the parish priest came to visit. Similarly, when tea first arrived in Wexford, it was steeped in hot water, then the liquid was thrown away, and the leaves were served on slices of buttered bread!

In the days when tea was still a luxury, people who developed a fancy for it were considered wasteful, and becoming known for excessive imbibing sometimes even cost a person his or her good name. Tin pots with pouring handles made by local tinsmiths were prized family possessions, and laborers rewarded for jobs well done with a hot cup of tea knew they had received the household’s highest praise. Until the mid-nineteenth century, tea was so scarce that it was only served on Sundays and church holidays as a very special treat.

By the time that sharing a pot of tea had earned its place as one more mark of good Irish hospitality, the compliment “Sure your mother never took the teapot from the fire” indicated someone had come from a good family. Refusing the offer of a cup of tea was unheard of and doing so could bring on the incredulous question “Is it leave with the curse of the house you’ll be doing?” Eventually, the Irish were drinking so much tea that it gave rise to the saying Marbh le tae agus marbh gan e (Dead from tea, and dead without it).

Today, it’s easy to see why tea with a drop of milk and a bit of sugar is nearly everyone in Ireland’s first choice beverage. Sitting down with a hot cuppa tay is a fine way to while away a few stolen moments especially when the leaves at the bottom of the cup just might foretell a bright and happy future. Sláinte!

Recipes

How to Brew a Pot of Tea

Fill a kettle with water and set it on the stove on high heat to boil.

While the water is heating, fill a china teapot with hot water. When the kettle has boiled, empty the teapot of its warming water and put in one teaspoon of good quality tea leaves for each cup of tea you want to brew.

Pour in the boiling water, cover the teapot with a towel or tea cozy, and let the tea steep for 3-5 minutes depending on how strong you prefer your tea. Serve immediately with milk and provide sugar for those who like their tea sweet.

Spotted Dog Tea Cake

3 cups all purpose flour

1 heaping teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon baking soda

4 ounces golden raisins

1 cup buttermilk

1 egg beaten

Preheat the oven to 450 degrees F. Sieve the dry ingredients, add the raisins and mix well. Combine the beaten egg with the buttermilk, and then make a well in the center and pour in most of the milk in at once. Using one hand, mix in the flour from the sides of the bowl, adding a bit more milk of necessary. The dough should be soft, but not too wet and sticky. When it all comes together, turn it out onto a floured board, knead lightly for a few seconds, just enough to tidy it up. Pat the dough into a round about 1 inch high and cut a deep cross on the top to let the fairies out! Let the cuts reach the side of the bread to make sure of this.

Place the dough on a baking sheet and bake for 15 minutes, then turn down the oven to 400 degrees F and bake another 30 minutes. To see if the cake is completely cooked, lif t it off the baking sheet and tap its bottom. If it is cooked, it will sound hollow. Remove the cake from the oven and let cool for approximately 30 minutes. Serve with warm butter.

Recipe courtesy: Mallymaloe House, Shangarry, County Cork.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June / July 2000 issue of Irish America.

When serving tea, my Irish nana would always insist on putting the milk in the teacup first.

When my nana was growing up in Tandragee, Count Armagh, she started reading tea leaves for the neighbours. Her mother put a stop to it when the line-up of neighbours wating at the back door started getting too long and interfering with the family’s peace and quiet!