180 years after his birth on June 28, 1844, the lessons of legendary Irish rebel, patriot, poet and activist John Boyle O’Reilly deserve to be remembered and cherished.

In today’s society of discontent and distrust mingled with guarded hope and optimism, O’Reilly would be hailed simultaneously as a disruptor of the status quo, a man unafraid to speak truth to power, a uniter not a divider, a change-maker. He would be recognized as both an American patriot and an Irish patriot in equal measure. He would be valued for his friendship and loyalty, for his unfettered curiosity and sense of adventure, and for his sense of purpose to something bigger than himself, namely, the principles of democracy, liberty and freedom.

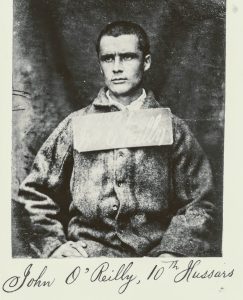

As a young man living in post-famine Ireland, O’Reilly (1844-1890) first gained notoriety as an escaped convict from an atrocious and imperialist brand of British justice. Sentenced at age 23 to life imprisonment for sedition against the Crown, he and his fellow Irish rebels were shipped to a penal colony on the outer edge of western Australia, a part of the world known as No Man’s Land.

Within months, O’Reilly made a daring escape, scrambling at night through the desert and the bush before rowing out to sea on a boat and jumping aboard the New Bedford whaling ship Gazelle that carried him across the high seas. The whaler was frantically pursued by British ships hoping to capture O’Reilly and prevent him from becoming another hero in the Irish cause.

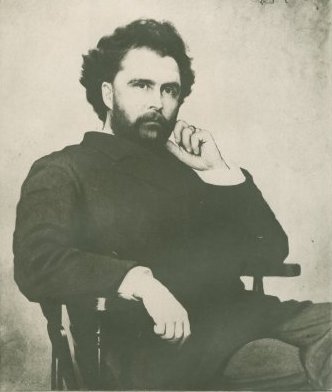

Arriving in America in 1869, O’Reilly spent a brief time in Philadelphia and New York City before visiting Boston in January 1870, where he quickly decided to settle. He spent the final two decades of his brief but shining life here, where his legend truly took shape. O’Reilly’s early infamy quickly turned to fame, for it was as a writer, orator and unabashed defender of the downtrodden that his lasting contribution to society became apparent.

A printer’s apprentice as a boy and a journalist briefly by trade, O’Reilly used his language and literary skills to secure a job at Patrick Donahoe’s Boston Pilot newspaper, the mouthpiece for Boston’s Irish Catholic community with a national readership. His first assignment was covering the failed Fenian invasion into Canada in April 1870, and before long he was promoted to editor and eventually became co-publisher of the newspaper.

The Pilot gave O’Reilly a perfect platform to pursue his most cherished cause: Ireland’s freedom from British rule. This advocacy caused the British to double down on their acrimony toward him; they refused to let O’Reilly return to Ireland for his father’s funeral in 1871 and vowed to arrest him if he came to Canada for a speaking engagement.

But he persisted, advocating for Ireland’s Land League and Home Rule movements, and welcoming Michael Davitt, Charles Stewart Parnell and numerous Irish leaders to Boston. In 1876 O’Reilly and John Devoy hatched a daring plan to rescue six of the remaining Irish prisoners still in Freemantle. They employed another New Bedford whaling ship, the Catalpa, to pull off one of the great escapes of the 19th century.

Perhaps O’Reilly’s most enduring contribution was his tireless efforts to reconcile the city’s fractured racial and ethnic factions. He immediately befriended the Yankee establishment, who admired his poetry and intellect, even while he firmly admonished them for their own prejudices. He defended African Americans seeking post-Civil War equality and Indigenous tribes being slaughtered out West. He was sympathetic to new immigrants such as Jews and Chinese, insisting that they deserved the same privileges as Americans.

O’Reilly’s active alliance and friendship with local Black leaders such as Frederick Douglas and Lewis B. Hayden put into motion a continuous tradition of respect, common purpose and mutual support between Boston’s Irish and Black communities that remains unbroken today, despite challenges and setbacks along the way.

In his famous poem about Crispus Attucks, a sailor of mixed African and Indigenous ancestry and the first victim of the Boston Massacre, O’Reilly posed the question, ‘Where shall we seek for a hero, and where shall we find a story?’ before praising Attucks and the other American patriots who stood up to British tyranny and created the United States of America.

O’Reilly’s power as an orator was legendary. He was chosen to recite original poems at the Boston Massacre Monument dedication on Boston Common, the Pilgrim Fathers Monument dedication in Plymouth, and Memorial Day and Veterans Day services in Everett. He spoke with passion and conviction at multiple gatherings, from the Thomas Moore centennial banquet at the Parker House and the gravesite of Fenian Thomas J. Kelly at Mt. Hope Cemetery to the Massachusetts Colored League convention at Faneuil Hall.

Leading American writers of the day such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman openly admired O’Reilly, and so did Irish writers Oscar Wilde and W.B. Yeats. In fact, Yeats credited O’Reilly as being among the first editors to publish his early poems in the 1880s.

In addition to his intellectual interests, O’Reilly was a celebrated amateur sportsman who believed in the physical, mental and spiritual benefits of sports. His 1888 book, Ethics of Boxing and Manly Sports, included a treatise on pugilism — he was friends with heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan — and sketches of O’Reilly’s canoe trips throughout New England and Pennsylvania. An essay in the book, “How to Grow Strong by Exercise, Training, Diet and Sleep,” was described by one newspaper as “probably the most complete study of this important subject ever made in this country.”

O’Reilly was an original founder of the now-famous Boston Athletic Association, founded in 1887. The BAA put together the American team for the first modern U.S. Olympic Games in 1896, and the following year, created the Boston Marathon, which the BAA still runs today.

He was affectionately called Boyle by his many friends and admirers and had a rich and fulfilling family life with his wife and four daughters.

Looking through today’s lens of social progress, O’Reilly had one glaring blind spot: he was adamantly against the women’s suffrage movement. He wrote in an 1885 editorial, “Women ought to be fully guarded by law in all rights of property, labor, profession, but roughly stated, the voting population ought to represent the fighting population.”

Had he lived beyond his 46 years, I like to believe O’Reilly would have tempered his views and gotten on the right side of history. His wife Mary Murphy was a talented writer whom he met at the Boston Pilot, and he encouraged numerous young women writers such as Katharine Conway, Louise Imogen Guiney, Fanny Parnell and Minnie Gilmore. After his death, three of his four daughters — Mary, Elizabeth and Agnes, went on to become trail-blazing women in the spirit of their cherished father.

As activists, educators and writers, the O’Reilly sisters collectively exposed unfair labor laws against women and children, started experimental schools, covered World War I as reporters from the front lines, lectured widely and published several books, all the while confronting hypocrisy and inequality wherever they found it. They would have surely made their parents proud.

Nearly two centuries after his birth and 134 years after his death, the answer to John Boyle O’Reilly’s poetic musing, ‘Where shall we seek a hero . . .’ may well be O’Reilly himself.

O’Reilly Landmarks in Massachusetts

Today, O’Reilly’s stature as a seminal figure in Irish and Irish-American history is particularly evident in his beloved birthplace of Dowth, County Meath; in Freemantle, Australia where he was imprisoned; and indeed, throughout the Irish Diaspora.

In Massachusetts, O’Reilly remains popular in Boston, New Bedford, Hull and Springfield where there is a selection of memorials and plaques, parks and city squares, library collections and Irish organizations honoring O’Reilly’s memory.

- In Boston, the John Boyle O’Reilly Memorial at the corner of Boylston Street and The Fens, not far from Fenway Park, was unveiled in 1896 by famed Concord sculptor Daniel French. The Memorial is part of Boston’s Irish Heritage Trail.

- In Charlestown, O’Reilly lived at 34 Winthrop Street, where there is a plaque in his honor. In 1988 the city placed an O’Reilly plaque in Thompson Square, and City Square Park honors O’Reilly with an inscription and bronze medallion.

John Boyle O’Reilly Tombstone, Holyhood Cemetery, Brookline, MA. - At Holyhood Cemetery, 584 Heath Street, Brookline, the centerpiece of O’Reilly’s gravesite is a giant stone from the church on which O’Reilly carved his initials with a nail as a young boy in Dowth, adorned with a bronze portrait bust of O’Reilly by sculptor John O’Donoghue. Each June, local Hibernians hold a mass at O’Reilly’s gravesite.

- The Boston Public Library and John J. Burns Library at Boston College each have replica O’Reilly busts by O’Donoghue and valuable collections of correspondence by and about O’Reilly and his daughters.

- O’Reilly’s summer home in Hull, where he died on August 10, 1890, from an accidental overdose of medication, is today the town’s public library. It is part of the South Shore Irish Heritage Trail.

- The Whaling Museum at 18 Johnny Cake Hill in New Bedford has great information about the city’s famous Whaling Ships of the 19th century, including the Gazelle and Catalpa.

- In Springfield, the John Boyle O’Reilly Club at 33 Progress Avenue was organized in 1904 by Irish immigrants living in western Massachusetts and remains active today.

Read more about John Boyle O’Reilly’s history in Donald Malligan’s Catalpa and learn more about Irish landmarks in Boston along the Boston Irish Heritage Trail.

Michael Quinlin is the author of Irish Boston (Globe Pequot Press) and editor of Classic Irish Stories (Lyons Press). He founded the Boston Irish Tourism Association, created Boston’s Irish Heritage Trail, and formed MassJazz to promote the vibrant jazz scene in Massachusetts. For more information about John Boyle O’Reilly, follow Michael Quinlin’s blog, Irish Boston History and Heritage.

Michael Quinlin is the author of Irish Boston (Globe Pequot Press) and editor of Classic Irish Stories (Lyons Press). He founded the Boston Irish Tourism Association, created Boston’s Irish Heritage Trail, and formed MassJazz to promote the vibrant jazz scene in Massachusetts. For more information about John Boyle O’Reilly, follow Michael Quinlin’s blog, Irish Boston History and Heritage.

Hi Michael,

Very very good. He’s all but forgotten back here. I’ve just finished my script on the Catalpa Rescue. Get in touch, if you wish. I live in Skerr

Frank

Thank you Frank, I’ll be in touch soon.

Hi Michael—

I am currently working on a Master’s thesis at University College Cork (but Boston-based) on John Boyle O’Reilly and came across your article. I’m still doing background work with his biographies and was wondering if I could talk to you about your research? I’m curious about how he seems to have faded from attention given his reputation and work in Boston not to mention everything else he accomplished in his short life.

Thanks,

Christine Kelley

Christine, I’m happy to talk with you. Please reach out to: irishmassachusetts@comcast.net.