From 1831 through 1916, the national Boston Pilot newspaper printed some 45,000 “Missing Friends” advertisements placed by friends and relatives in attempts to locate loved ones lost during emigration. These ads, consolidated into edited volumes, provide a valuable record of a poor emigrant population trying to reach one another. Several of these volumes were edited by Emer O’Keefe, who spoke with Kara Rota about what the listings provide for the descendants of Famine emigrants.

“Since it was a very large movement of people, many of whom left little behind, it’s hard to know the personal stuff,” said Emer. “This is what the ads provide; they speak directly to us, and this intimacy makes them appealing. John Fallon ‘had light hair, blue eyes; was about four feet, four inches in height; wore a blue spencer, a new scoop shovel cap, a fancy pants and had a freckled face.’ You can really see this boy! You can often glimpse a personality. Thomas Sullivan was described by as his wife as ‘of medium height, brown hair, fair complexion, and free in conversation.’ The vulnerability of individuals left stranded is also clear. James Rourke’s wife and children were ‘daily mourning his absence.’ Catherine Kelly sought her husband, signing herself “the mother of his four living children.’ The voices of these emigrants resonate still.”

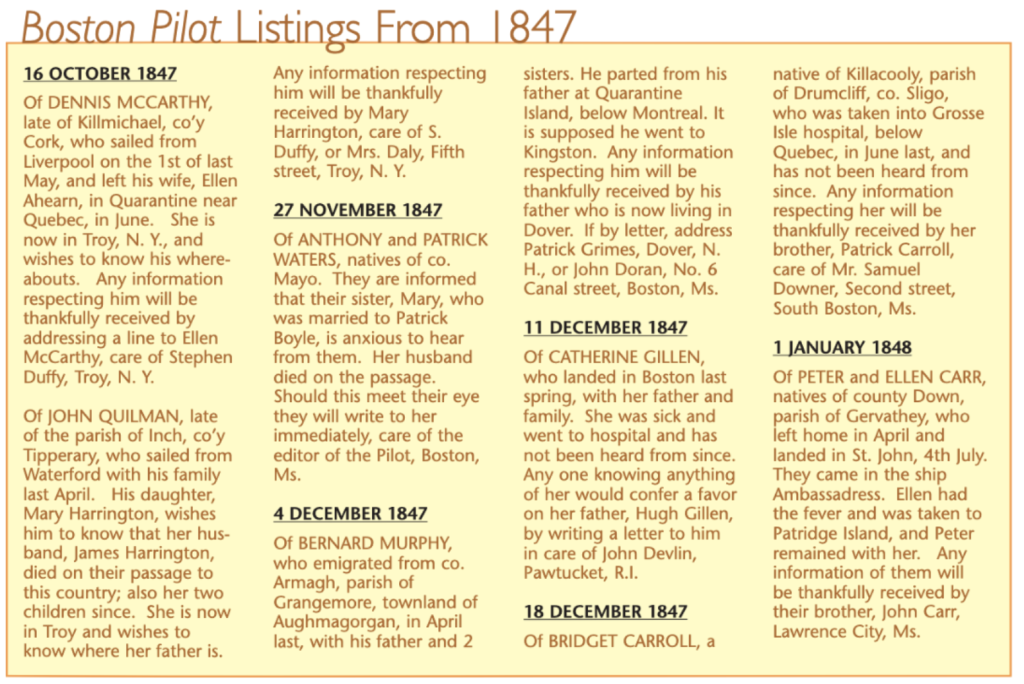

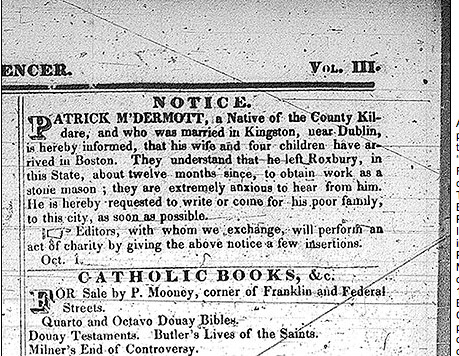

In their own words, through the Boston Pilot listings, emigrants express their hope, fear and loss. “The ads run the gamut of immigrant experience and the tone reflects this,” Emer O’Keefe said, “From personal emotions – vulnerability and loss, hope and pride when things are going well – to the larger social movements. The tone of the 1847 listings, for example, is very different from that of the 1890s when the immigrants are more prosperous and social networks much more evolved. … [Famine emigrants] certainly didn’t give up the hope of locating [their loved ones]. Many immigrants placed ads again and again for family they might not have seen or heard from in decades. And the ads weren’t cheap: thousands paid their daily wage and more ($1) for an ad that would run three times.”

Emer O’Keefe embarked on this project with a personal resonance. “I came to the U.S. in 1983 to attend Northeastern University’s graduate history program,” she told Irish America. “The 1980s was a very grim time economically in Ireland, with huge numbers of people emigrating to the U.S., England, and Australia. Most of my undergraduate class ended up emigrating. But I was the only member of my large family to leave home, and back then it wasn’t as easy to stay in touch. We didn’t have cell phones or e-mail, and phone calls were more expensive. We wrote a lot of letters! It was easy to empathize with the homesickness many of the immigrants experienced; as well as the need to stay connected with family and to create an Irish community in America.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June / July 2010 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply