Between 1845 and 1855, some 1.8 million left Ireland for Canada and the United States. Those who were lucky enough to survive the brutal journey to the New World were motivated by the hope of new possibilities, including the promise of employment.

Ten thousand Micks

They swung their picks

To build the new canal

But the choleray was stronger’n they

And killed ’em all away.

Ballad, 1800s.

Irish labor became an invaluable resource for the development of America in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the Midwest and Far West, the Great Lakes region and upstate New York, farming and ranching were common trades for Irish immigrants. In the East, labor contractors hired men to work in ‘labor gangs’ that built railroads, canals, roads, sewers and other construction projects. Their work provided a significant portion of the labor that built infrastructure in expanding cities. Over 3,000 Irish helped to build New York’s Erie Canal, which had to be dug with shovels and horsepower, and thousands more worked on railroads, farms, and in mining. In mill towns in New England, Irish provided low-cost labor at textile mills. Some, including children, worked long and dangerous hours at factories. Within view of the Western New York Irish Famine Memorial are the Erie Canal and the grain and steel mills where the Irish helped to build American industry and solidify their place in the country.

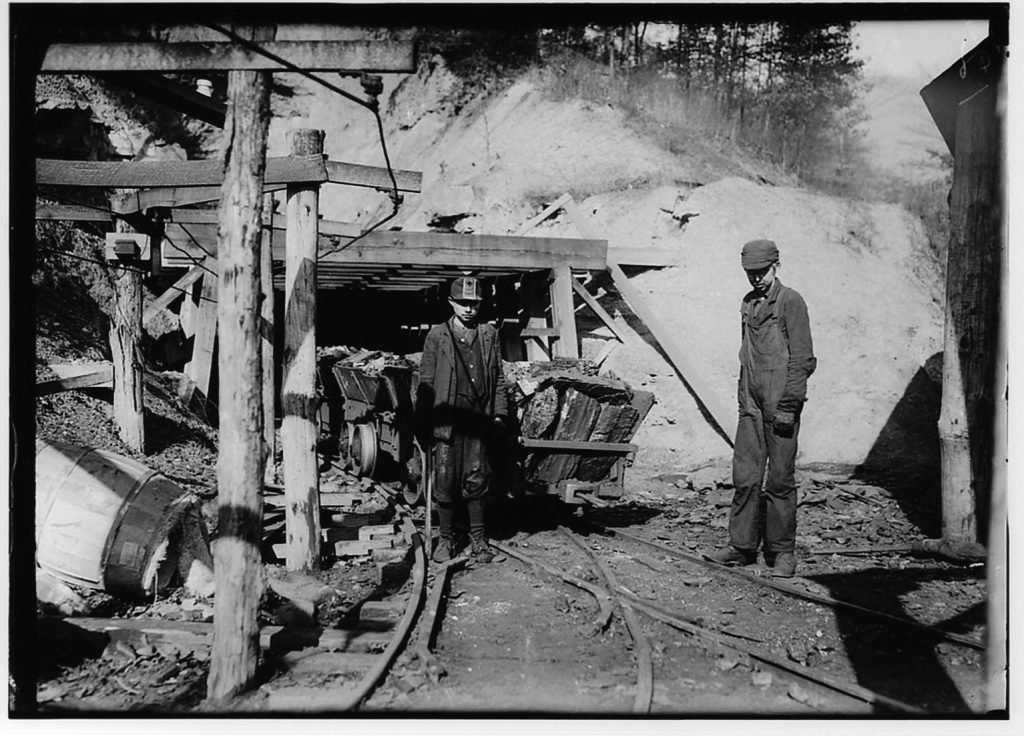

Many men who had in Ireland been unemployed or worked as basic laborers and farmers found work in mines. The work was dangerous and caused many health problems, and only low wages for long days were offered as reward. Miners lived in ‘mine patch’ communities, overcrowded and crudely built towns in which the housing, the community stores, and the land were all owned by the mining companies, characterized by mine bosses whose practices included intimidation and oppression to avoid worker unrest or complaint. Miners’ children worked in breaker rooms, where they picked off slate from coal and broke coal lumps.

In the Southern United States, slave owners considered the Irish less valuable than slaves, as they were not property, and therefore a better population to execute cheap and highly dangerous labor. They were often employed for construction projects, in the course of which hundreds and thousands of Irish would die, often paid only a dollar a day for their trouble.

In New Orleans, the Irish played a major role in the building of the New Basin Canal. An outbreak of yellow fever meant that workers were dying in large numbers, and as slaves were judged to be too expensive to lose, Irish immigrants who were desperate enough to take on the dangerous and difficult work for $1 a day became the preferred labor. As boatloads of Irish continually arrived, the New Orleans Canal and Banking Company had no trouble replacing the Irish that died by the thousands. When the canal opened in 1838, 8,000 Irish laborers had succumbed to cholera and yellow fever. Over the following decade, the canal was enlarged and shell roads built alongside it. While there are no official records of immigrant deaths, somewhere between 8,000 and 30,000 are believed to have perished in the building of the New Basin Canal, many of who are buried in unmarked graves in the levee and roadway fill beside the canal.

Mills also began to hire more Irish during the influx of Famine immigration. “No Irish Need Apply” signs were prevalent through the 1830s, and some Irish women were segregated when first hired in mills in Lowell, Massachusetts, where Yankee Prostestants called ‘Lowell Girls’ had previously held the majority of the jobs. However, by the 1850s mills were hiring the Irish regularly because they would work for less money and did not make the same demands for reasonable working conditions that Yankee mill girls were beginning to stand for in their historically famous strikes. Between 1828 and 1850, Lowell’s population grew from 3,500 to 35,000. In 1860, approximately 62 percent of Lowell’s textile workers were immigrants, half of whom were Irish.

The Connecticut River Valley saw a large number of Irish immigrants in the wake of the Great Famine, and many settled in Hadley Falls, Massachusetts, the upcoming industrial center upriver from Springfield which was renamed Holyoke in 1850 to fight negative attitudes towards “the Irish Parish.” Some 5,000 Irish settled there by 1855 and built a dam and a series of canals that would provide water power to mills and factories, primarily for textiles and paper. Local Catholic churches played a vital role in forming a sense of community and pride to the Irish in Holyoke, a legacy that continues to this day in the Holyoke St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

Some Irish immigrants went west towards California, especially San Francisco, to seek their fortune in the Gold Rush of 1848-1855. San Francisco’s Irish population grew to 4,200 by 1852 and 30,000 by 1880, and the Irish were the largest group of foreign-born workers in the city by that year. There was no easy way to travel to California, either by ship or the treacherous 2,200 mile journey by land that could take three or four months, at an optimistic estimate. Gold mining was difficult and time-consuming work, and one bucket of soil might turn out only ten cents’ worth of gold. One estimate is that one in five miners to arrive in California in 1849 died in six months of disease, hunger, accidents and injury, or violence.

In 1859, two Irishmen named Peter O’Reily and Patrick McLaughlin found silver in what is now Virginia City, Nevada (then western Utah Territory) in the famous Comstock Lode of silver ore. Their discovery brought thousands of Irish to Nevada, and Virginia City was one-third Irish by the mid-1870s. The ‘Bonanza Kings’ or ‘Irish Four,’ John Mackay, James Flood, James Fair and William O’Brien, made their fortunes organizing the Consolidated Virginia Silver Mine near Virginia City, Nevada.

The earliest gold discovered in Montana was in 1858 in Gold Creek. More discoveries followed in Bannack in 1863 and then Virginia City. Ultimately Montana would become known for its rich deposits of copper, and an Irish man, Marcus Daly, who was born in County Cavan in 1841 and immigrated to New York at the age of 15, become known as The Copper King for the fortune he made from the Anaconda Copper Mine in Butte.

The Civil War and war with Mexico provided a place for many Irish men to serve. Men were enlisted to fight in the Civil War as they arrived in the U.S. at Governor’s Island in New York. A full 150,000 Irish-born Americans fought with the Union army, about one third of who came from New York, and while statistics for the Confederacy are less solid, the Irish were certainly among their ranks as well. Thomas Francis Meagher and Michael Corcoran led the Irish Brigade and the Corcoran Legion to fight for the honor of their home country and the salvation of their adopted one on the Union side. With the exception of the 116th Pennsylvania, which carried the state flag, the regiments in the Irish Brigade and Corcoran Legion carried the Irish green flag with gold harp, usually with a Gaelic battle cry added for effect. During the Civil War, the Medal of Honor was created and has since been awarded to 3,401 men. Ireland is the birthplace of the largest number of medal recipients, with 258 Medals of Honor. Five of the 19 men who won a second Medal of Honor were also born in Ireland. In fact, the recipient of the Medal of Honor for the first action in which one was awarded, Bernard J. Irwin, was born in Ireland in 1830.

By 1860 some 4,000 miles of canals were spread out across America, mostly dug by Irish immigrant labor. Many of those same immigrants and newer immigrants moved on to work on the railroads. It was dangerous work. There was an expression heard among railway men: “an Irishman was buried under every tie.” If a worker was injured, he was fired. If he was killed, his widow and family went without.

Many new immigrants, women in particular, found employment as factory workers, or as domestics, cooks and maids, in affluent homes such as those on Boston’s Beacon Hill and along New York’s Fifth Avenue. Studies have shown that women emigrated as often as men from Ireland, and at equally young ages. Some sociologists give the role of female Irish domestic workers credit for neutralizing American attitudes in regards to Irish immigrants, as they experienced personal interaction in the intimate spheres of family lives and the private American home. Irish women, known familiarly as “Bridgets” or “Biddys,” were often hired as servants at hiring fairs, and were usually taken on for a six-month or other given time period, largely as indentured servants or with only a small compensation aside from room and board. However, these domestic jobs were luxurious compared to the tragedy unfolding in Ireland or the cramped spaces of ‘Shanty Towns’ where Irish immigrants were crammed in urban areas. “Bridgets” sent significant portions of what money they did earn home to Ireland, an estimated total of $260 million between 1850 and 1900.

Whether running American households, building American infrastructure, fighting American wars, manufacturing consumer goods or seeking their fortune out West, Irish immigrants sacrificed their lives in great numbers in the name of the country on whose shores they had arrived, in huddled masses, tired and poor but not necessarily welcomed by the nativists that met them there. The labor that the new Irish Americans contributed cemented their role in the development of the country they now called their own.

Thanks for this article, Patricia. Badly needed at this time.