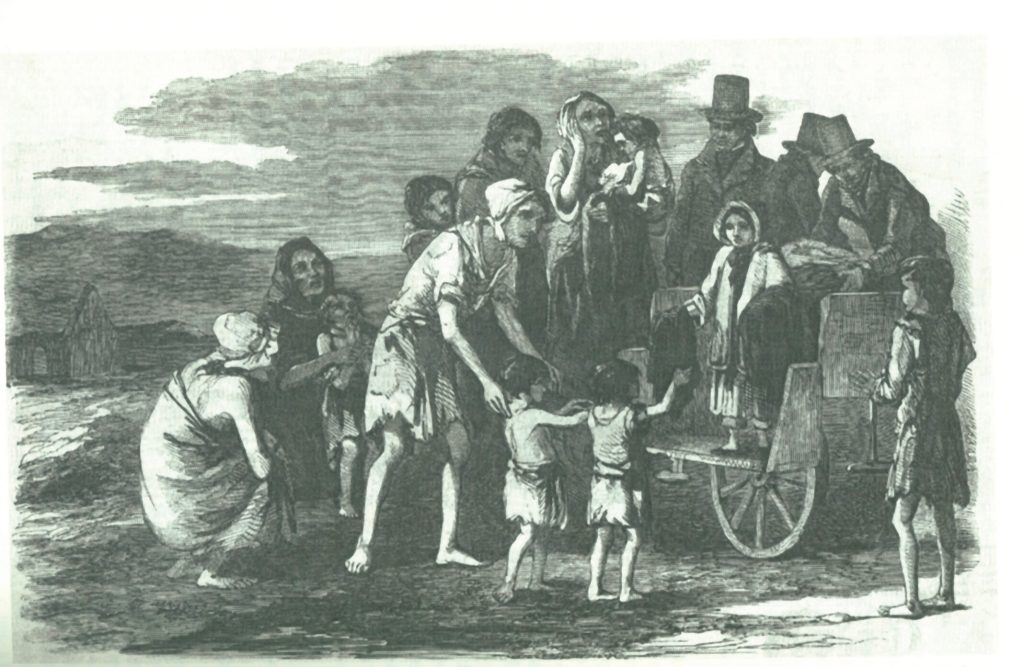

During the worst winter of the Famine, the American reformer Asenath Hatch Nicholson began her one-woman relief operation, organizing a soup kitchen, visiting homes of the poor and distributing bread in the street.

In May 1844, Asenath Nicholson left New York aboard the Brooklyn to “personally investigate the condition of the Irish poor.” She had been a schoolteacher in Vermont and in New York, a proprietor of a vegetarian boarding house and a reformer who championed the causes of abolitionism and temperance. From her boarding house on the edge of New York’s notorious Five Points, she worked among Irish immigrants. She later recalled those years saying, “It was in the garrets and cellars of New York that I first became acquainted with the Irish peasantry, and it was there I saw that they were a suffering people.” She was determined to learn more about their suffering by walking through the country on her self-appointed mission to bring the Bible to the Irish poor. It was an ambitious adventure for an arthritic widow of fifty-two. She would distribute copies of the Bible to those who could read, and she would read the Bible to those who could not.

Dressed in her polka coat, bonnet and Indian rubber boots and carrying an enormous black, bearskin muff from which she produced tracts and Bibles, Nicholson must have been an extraordinary sight. She complained that people stared at her. Her mission was not as straightforward as it might appear. Catholics regarded Bible readers as proselytes, and Protestant missionaries rejected her democratic ideas. From July 1844 to August 1845, she walked through Ireland visiting every county but Cavan.

She left for Scotland in August 1845, shortly before the first signs of the potato failure appeared. While Nicholson had not anticipated the failure of the harvest, as she traveled around the Irish countryside she frequently observed that the Irish poor depended on a single food crop. She had heard the libel that the Irish poor were lazy; however, based on her experience visiting the Irish in their cabins, she concluded that they were not lazy; they lacked work. When she saw the poor employed, she made note of it. The sight of a woman and her daughters carding and knitting gave her pause. “This was an unusual sight for seldom had I seem, in Ireland, a whole family employed among the peasantry. Ages of poverty have taken everything out of their hands but preparing and eating the potato and then sit listlessly on a stool, lie in their straw or saunter upon the street because no one hires them.”

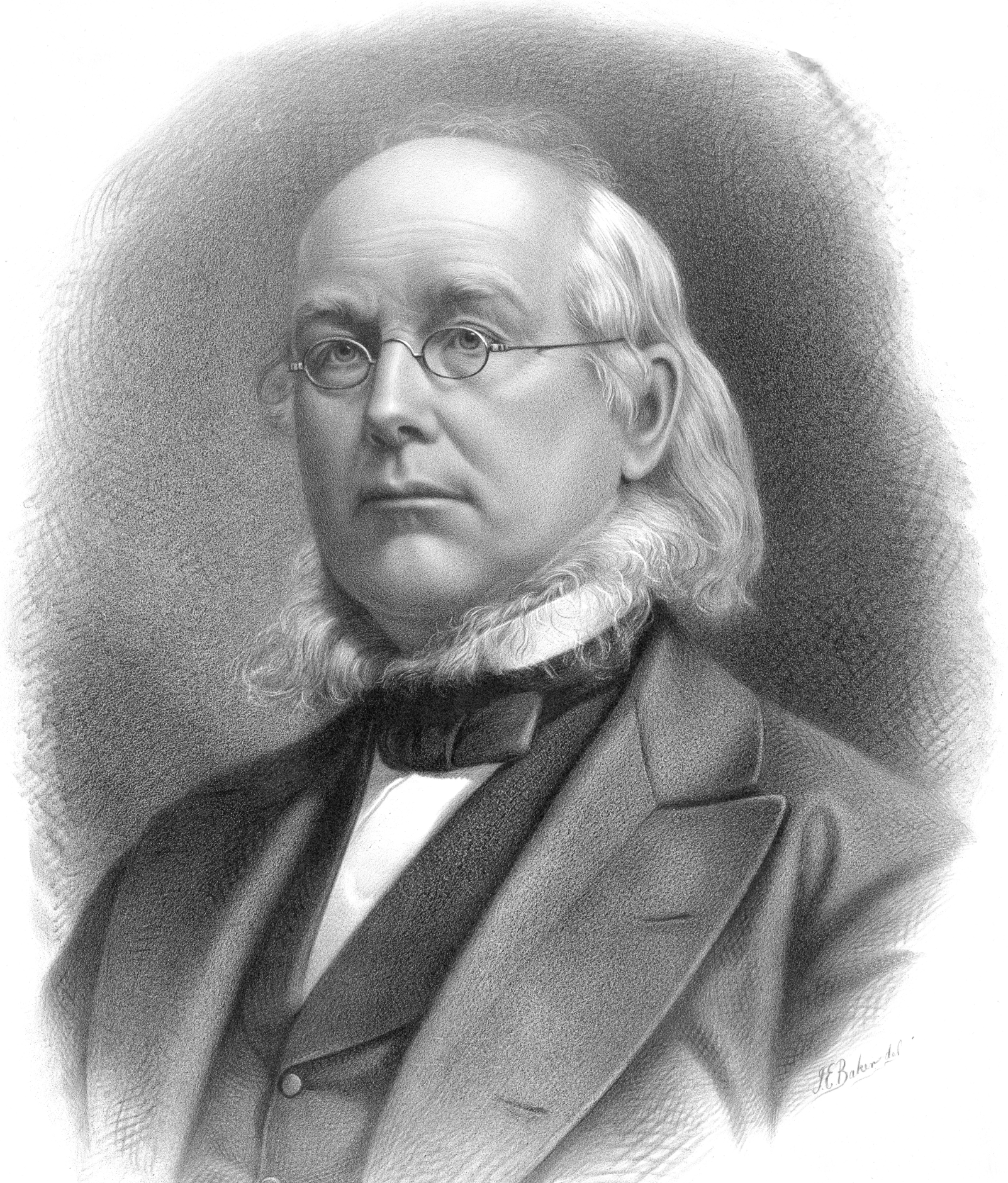

A crop failure combined with chronic unemployment would turn a natural disaster into a calamity. When the blight came a second year, Nicholson returned in the winter of 1846 to do what she could do to help. She stayed two years spending much of that time in the famine-stricken west. As soon as she arrived in Dublin on December 7, 1846, Nicholson wrote to the readers of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune and Joshua Leavitt’s abolitionist Emancipator describing conditions in the city and asking for help for the Irish poor. She did not have the means to finance her relief efforts and she despaired that she was brought to witness a famine without the means to relieve the hungry. When a letter arrived from Greeley with money from his Tribune readers, she regarded it as not only as the answer to her prayers but also a sign of Divine intervention. Other friends send food, money and clothes to distribute or to send to trusted friends to administer. In July 1847, New Yorkers sent Nicholson five barrels of Indian corn aboard the United States frigate Macedonia. (There were fifty barrels aboard for Maria Edgeworth who provided the Central Relief Committee with information about famine conditions in Co. Longford and who asked for shoes for her tenants working on a draining project to wear.)

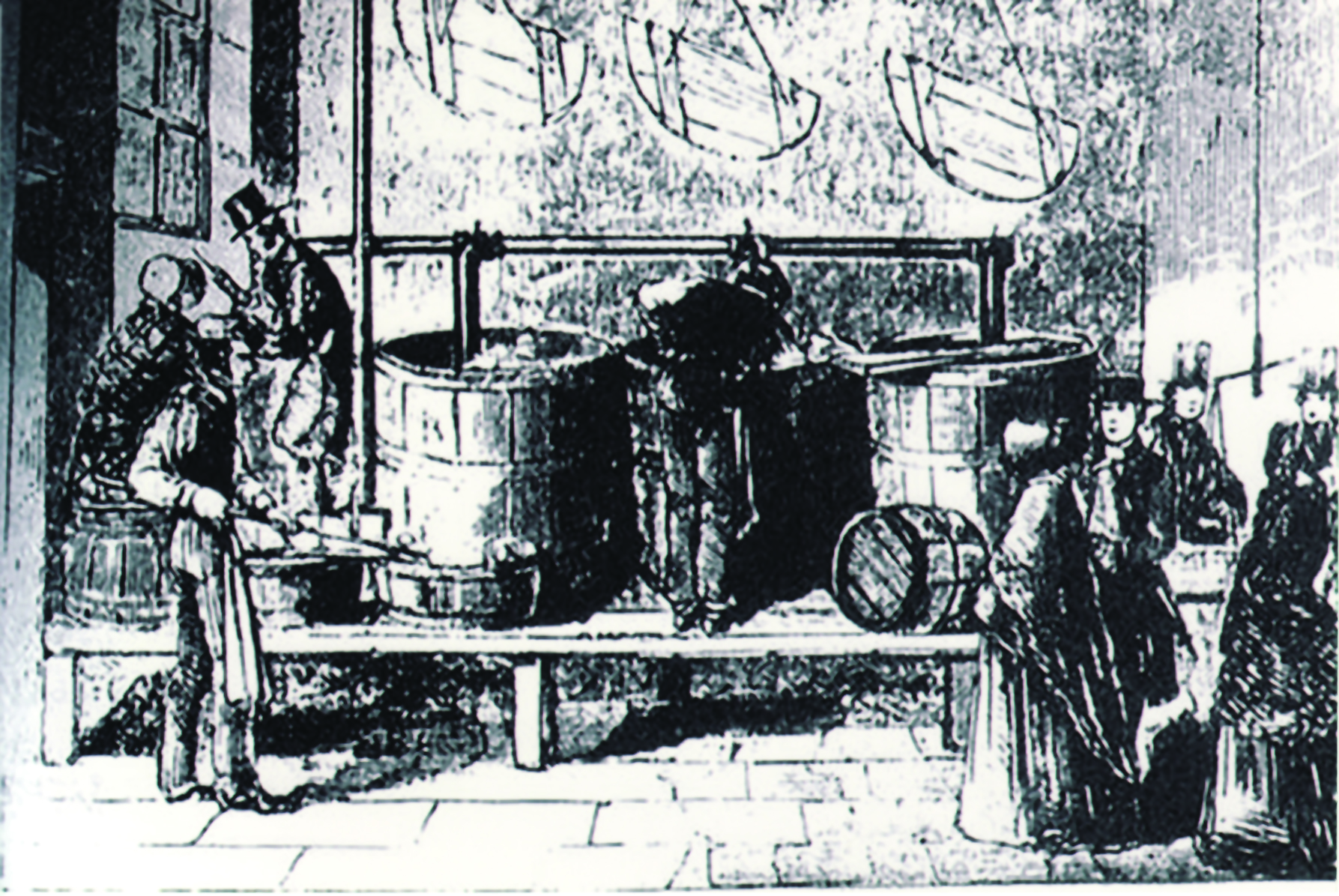

While she admired the work of the Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends (Quakers) who had established a soup kitchen in Charles Street behind Upper Ormond Quay in January 1847, Nicholson preferred to operate individually as she had in the Five Points and in her earlier trip to Ireland. She described herself walking through Dublin each morning distributing slices of bread from a large basket. She worked out of her own soup kitchen in the Liberties, an area she selected for its extreme poverty. The Quakers sold their soup for a penny a quart. Nicholson’s food was gratis; however, she operated on a triage system. She decided that £10 divided among 100 people helped no one, so she committed herself to a particular group of families for whom she cooked Indian meal daily.

Nicholson stayed in Dublin until July 1847 when she left for Belfast. By then she had finished Ireland’s Welcome to the Stranger, her account of her earlier visit written to encourage readers to respond to Ireland’s crisis. By then the Temporary Relief Act (the “Soup Kitchen” Act had become effective, and the Quakers closed their kitchen. Nicholson may have followed their example. In any case, she left Dublin and went for the west of Ireland in July 1847 where she visited Donegal and then went on to Newport, Co. Mayo. She had visited Newport earlier and was returning to stay with her friend, the postmistress Mrs. Margaret Arthur. There she found “…misery without mask.”

She went further into the misery when she went west from Belmullet to spend the winter of 1847-8 in the Erris peninsula. She set to work bearing witness to the suffering, visiting the poor and encouraging relief workers. She not only recorded their names, but she also gave a glimpse of those selfless people who died working among the poor: Rev. Patrick Pounden, the Rector of Westport and his wife and Rev. Francis Kinkaid, the Church of Ireland curate of Ballina who died on the 28th of January 1847. Catholics as well as Protestants contributed to the memorial tablet on the wall of the church.

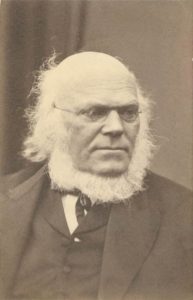

She continued to lobby in letters for ways to bring employment to the people of western Mayo. On October 31, 1847, she wrote to her friend the English Quaker philanthropist William Bennett who had visited the west of Ireland early in 1847. She was quick to praise resident landlords who provided employment for their tenants, but some were unable to provide relief. “You, sir, who know Erris, tell, if you can, how the landlord can support the poor by taxation, to give them food, when the few resident landlords are nothing and worse than nothing, for they are paupers in the full sense of the word.” She went on to ask Bennett to use his own resources or his influence to support a local employment scheme. “I must and will plead, though I plead in vain, that something may be done to give them work. I have just received a letter from the curate of Bingham’s Town saying that he could set all his poor parish, both the women and children, to work, and find a market for their knitting and cloth, if he could command a few pounds to purchase the materials.”

Nicholson not only appealed to her friends and to the public, she challenged the government on two counts: their stewardship of relief resources and their attitude toward the poor for who they were responsible. She made a distinction between the paid relief officers whom she characterized as bureaucratic, hierarchical and self-serving and volunteer relief workers (Quakers, coast guardsmen and their families and local clergy) who were compassionate, egalitarian and selfless. Nicholson was scrupulous about her own expenses. She allowed herself twenty-three pence a day for food: a diet of bread and cocoa and she reduced her stipend to sixteen pence (no cocoa) when her resources dwindled. She raged that grain was diverted from food to alcohol. She charged that grain used for distilling could have fed the Irish poor. “Reader, ponder this well. Enough grain, converted into a poison for body and soul as would have fed all that starving multitude.”

Over and over she contrasted the lack of charity among relief officials with the compassion of volunteers. The hospitality of the Irish countryside was the leitmotif of Ireland’ s Welcome to the Stranger; the leitmotif of Annals, was the generosity of the poor to one another. Annals is a vivid account of suffering that combines her eye-witness account with character sketches, parables, dramatic scenes and dialogues. Nicholson’s accounts put human faces on the statistical reports. Her account of those who served the poor is a record of grace.

In the fall of 1848, when she thought the Great Irish Famine was over, Nicholson left Dublin quietly for London. In fact, famine conditions continued until 1852. The “lone Quaker” who saw her to her boat was probably her friend the abolitionist Quaker printer Richard Davis Webb. In England she published Lights and Shades of Ireland (1850), the third part of which was “Annals of the Famine,” She joined the cause of world peace joining delegations to Paris and Frankfurt. She returned to New York without notice and lived quietly in declining health until she died of typhoid fever in Jersey City on May 15th, 1855.

Almost forgotten, her books are now back in print, so we know how she would have wished to be remembered. During her first visit to Ireland while walking the road from Oranmore to Loughrea, Nicholson stopped to rest her blistered feet and thought of her prudent friends who had warned her against this reckless adventure. Did she wish to be back in her parlor in New York? She did not. She said, “Should I sleep the sleep of death, with my head pillowed against this wall, no matter. Let the passerby inscribe my epitaph upon this stone, fanatic what then? It shall only be a memento that one in a foreign land lived and pitied Ireland, and did what she could to seek out its condition.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June / July 2010 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply