In the tradition of great educators who helped the Irish grab the first rungs on the ladder of success, Dr. John Lahey, President of Quinnipiac University, reminds us from whence we came and the struggle to get where we are. As founder of Quinnipiac’s Great Hunger collection, he is the guardian of a remarkable treasure of history that we can’t escape.

As president of Quinnipiac University for the past 23 years, John Lahey has played a vital role in educating the public about the story of the Great Hunger. Through his appearances as Grand Marshal of New York’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade in 1997 and the Great Hunger Lender Family Special Collection at Quinnipiac that came into existence soon afterward, Lahey has championed the need for the history of An Ghorta Mór to be accurately and completely told. Quinnipiac’s collection is one of the most extensive collections of art and literature in America devoted to Ireland’s Great Famine.

Lahey recently wrote a letter to The Wall Street Journal in response to a column by William McGurn, “My Wild Irish Woes,” which asserted that Great Hunger memorials emphasize defeat rather than pride, and explained his need to clarify his disagreement with McGurn’s stance. “I’m an educator, so I think accurate historical facts and explanations of events and history are important,” said Lahey. “It’s a fact of the Famine that the story wasn’t told accurately, it wasn’t told in a balanced way. … The Irish were citizens of the UK, and clearly the [English government] showed a callous disregard for human life and basically used a tragedy that wasn’t of their making, in the sense that it was the potato failure itself, and allowed it to be used for land reform and other economic and political desires on their part. They allowed a million and a half people to die of starvation and another two million plus to leave the country, and basically decimated the country. None of that was really told; as you can imagine, no art was produced, reporting that or commemorating that at all. . . . So it’s really just beginning something that really should’ve been done 150 years ago, that under more normal circumstances would’ve taken place and so that’s why it’s important to do it now.”

Lahey’s roots are in Knockglossmore, a town outside of Tralee in Kerry. His paternal grandfather, Daniel Lahey, was born there and emigrated to Canada and then to New York City. His grandfather was a stonemason and brought the trade to America, where Lahey’s father worked as a bricklayer in New York. Daniel Lahey married a Roach from Cork. Lahey’s mother’s family were Griffins, from County Clare, all areas that were affected deeply by the Great Hunger.

In 1997, Lahey was asked to serve as Grand Marshal of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York City, and decided to use the platform to speak about the Famine, the details of which had recently been brought to his attention.

“I read Christine Kinealy’s book, This Great Calamity, in 1995. When you see the painstaking detail that she went to in terms of the research and talking about the food and the shipments on the boats and the records, you see that for a five year period of time, in fact, very little was done to ease the suffering, the ports were not closed. In the years that she documents, food was shipped out of Ireland in increasing amounts in the years of the Famine. … Then it was just a year or two later that I was approached to be Grand Marshal of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in 1997 and I wanted to make the Great Hunger the theme of the parade that year. … Normally they announce the Grand Marshal in the November/December time period, so from January 1 to March 17, all the Irish organizations, the county organizations, the AOHs, they all have their annual events and they invite the Grand Marshal to come to the events. You’re expected to go to 25, 30, 40 events, literally I think there’s almost 200 invitations. I didn’t think my own Irish life was all that interesting; a lot of the Grand Marshals talk about themselves, but being the educator I am, I wanted to use that opportunity and that platform to talk about the Great Hunger, so I did.”

His speeches brought the cause to the attention of Murray Lender, a Jewish immigrant whose father fled persecution in Poland, came to New Haven, and started a bagel business that became Lender’s Bagels, a multi-hundreds-of-millions-of-dollars company that was ultimately sold to Kraft approximately 15 years ago. “While I was giving all these speeches [as Grand Marshal], he came to me and said, ‘John, it’s just amazing to me, this story of the Great Hunger.’ You could tell that he associated it with persecution of the Jews and other ethnic groups, African Americans, Native Americans, in this country, and he said, ‘I’ll give you a gift for the library but it’s got to be for the Irish Great Hunger special collection. You go out and tell me what you need to do and collect the art and get the research materials and the books and periodicals, and I and my brother, Marvin Lender, we’ll take care of it.’”

With this outside help, Lahey began collecting materials for the special collection. “[Rowan Gillespie’s The Victim] was my first piece. I literally carried it on the plane [from Ireland] with me, I wouldn’t let it go. It was such a powerful piece; the facial expression just captured everything about the suffering and pain. Later in that same summer I’d just come back and we went to a Westport art show and I saw Margaret Chamberlain work, a sculpture of tormented people with psychological things and I could just tell that this artist was able to capture the torment, and I commissioned her to do the original piece The Leave-taking. I must say for me though the most powerful piece, we just have a miniature version of it, is John Behan’s The Famine Ship. I can remember when I was with my son and we parked the car in the parking lot. It’s not easy to get to Croagh Patrick, you have to pretty much know where you’re going and what you’re looking for. When I parked the car, the parking area is kind of across the street and it’s a bit of a walk to get to it, I mean, you can kind of see it off in the distance, it’s very big, and it looks from a distance like a sailing ship, like the netting or whatever, and it’s not until you get – and my distance vision is not that great, so maybe some people can see it for what it was a little earlier, but it wasn’t until I got pretty close to it that you see the skeletons stretched across it. First of all, it’s got largess, but it’s I think the most powerful piece I saw in terms of original art that’s there permanently displayed.”

The collection has since outgrown the space that was originally set aside for it, and Lahey plans an expansion for the near future that will bring it to the attention of a larger public. “We own a good sized building on Whitney Avenue and we have some people in there right now, some different offices, but our plan is to move them out over the next few years and to turn that into a Great Hunger Art Museum. And it’ll be appropriate, it’s not going to be the size of Yale’s British museum down there but it’ll be just up the street a bit, which will do a couple things. One, it will allow us to display much more of the collection than we’re currently able to display just in that room where you literally have to walk through the library. The other thing is that while it’s open to the public, people just – it’s not welcoming, they have to literally come on the center of campus so we don’t get quite the visitation we’d really like to get. Whitney Avenue is a very public place, the main street which runs all the way from Hartford to New Haven. We can get very public signage and there’s plenty of parking there and that will allow the collection to be much more accessible and we can have public events there and so on.”

Lahey sees the Great Hunger collection as a way to depict the importance of human intervention in crises that stem from natural causes. “We need to educate people that many of these things were just, unfortunately, human beings not reacting in ways that they could have, not having the right amount of compassion or political will. If you think of the recent experience in this country with Hurricane Katrina, you can’t blame anyone for the hurricane itself, that’s the natural cause of it, but the ineptitude and callousness of the response of the federal government and local authorities and others just turned a crisis into a true disaster. …When you’re dealing with life and death and people displaced and homeless and starving and health issues, you need to throw the rules out the window and as a society come together and – that’s why even during the Great Hunger, the English argue, well, that was the approach back in those days, laissez faire policy, and sure they could’ve closed the ports but that was private food – well, no, that’s what we should’ve done. And there were actually incidents prior to that in Ireland where it was handled much better. The subsistence crisis back in the 18th century is not remembered at all because of that, as opposed to how the Great Hunger almost fifty years later was mishandled.”

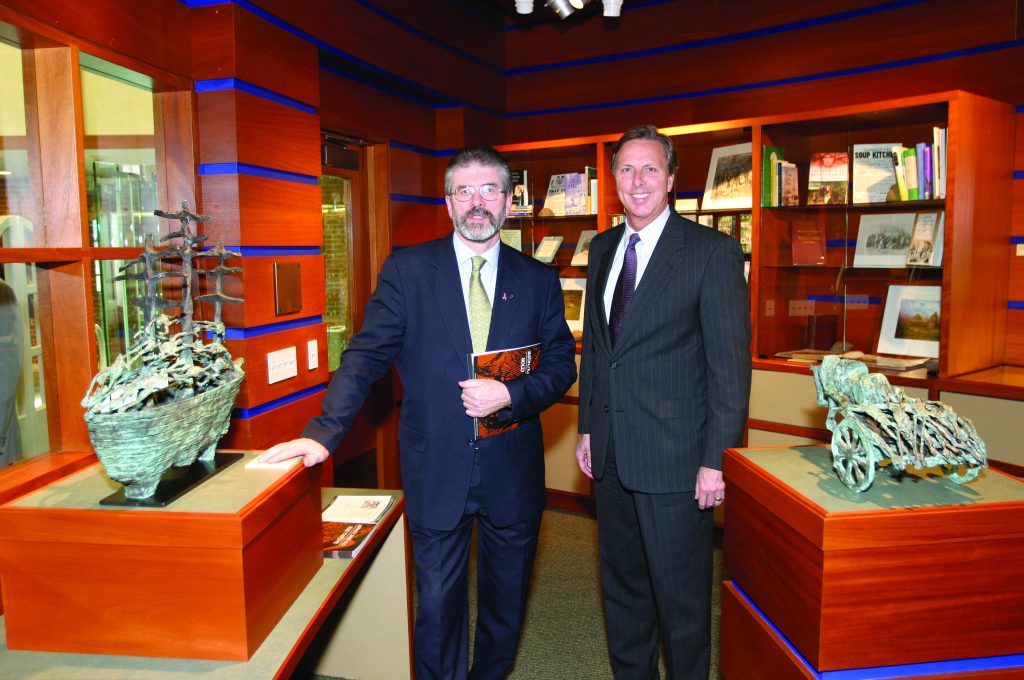

In his years overseeing the Great Hunger collection and giving tours of its contents, Lahey recalls one moment in visitors’ reactions that stands out for him. “We had Gerry Adams speak at Quinnipiac, I think it was two years ago. I brought him down to the library and he walked in the room and I started to do my normal presentation, you know, this is John Behan’s piece of art, this is one that we commissioned from Margaret Chamberlain and so on, and then I walked him over and said this is Rowan Gillespie’s piece, The Victim, and then I went on and I was on to the next one before I realized, I looked back and Gerry Adams was standing there, he couldn’t move. He was just overwhelmed by, I think, the fact that a university that he didn’t know particularly anything about in Connecticut would have a collection dedicated to the Great Hunger. And the power of that piece. I think people seeing the collection for the first time, they’re very clearly moved by it.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June / July 2010 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply