Aífe Murray tells Irish America the story of how an Irish maid influenced Emily Dickinson’s poetry and saved it from destruction.

Genius does not exist in a vacuum. This was the message taken away from Aífe Murray, author of Maid as Muse, when she spoke at Glucksman Ireland House on March 25th. The topic was Emily Dickinson, whose poetic prowess has been understood as the product of a reclusive lifestyle for the past one hundred and fifty years. Dickinson witnessed the shaping of a country during the unending turmoil of the Civil War and the assassination of Lincoln. But unlike her contemporary Walt Whitman, who became the mouthpiece for a kinetic city overflowing with new immigrant life, Dickinson’s poems reflected her own circumstances, the solitary spaces of her own mind.

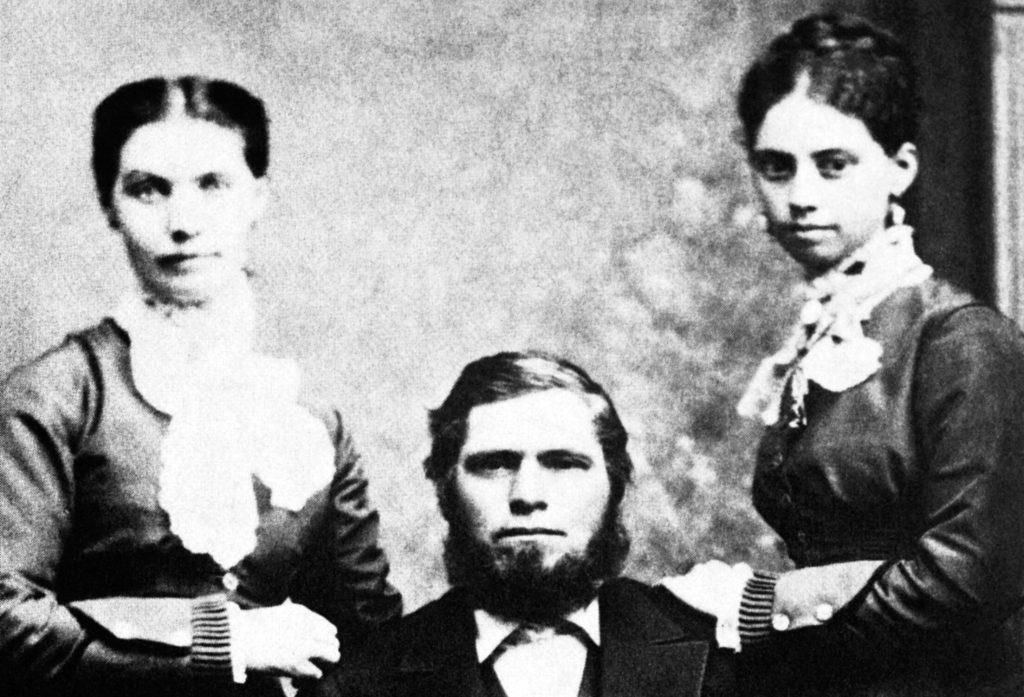

The portrayal of Emily Dickinson in most American classrooms is a grim one – the anti-social Dickinson sat in her room for most of her life, writing poems with strange grammatical impulses and macabre subject matter seemingly from another world. The sheer volume of her work attests to this theory – over the course of her lifetime, Dickinson wrote almost 2,000 poems and countless letters. The perception of Emily Dickinson as the lone literary wolf Amherst has persisted unchallenged – Dickinson has no living descendants and her place in the canon of New England literature has long been cemented. What new research could possibly rock Dickinson scholarship after practically every stone of her life had been unturned? It was a small fact that seemingly had no immediate connection to Dickinson’s poetry: Emily Dickinson shared her kitchen with an Irish immigrant for the last 17 years of her life. She wrote on whatever she could—a chocolate wrapper, old shopping lists – all while baking for her family’s household alongside Tipperary-born Margaret Maher. That relationship was all but forgotten until Aífe Murray came across a picture in the library that inspired over ten years of art, poetry, education and research.

In her new book Maid as Muse, Aífe Murray explores the relationship between Emily Dickinson and her Irish servants, focusing on the Maher and Kelly families. In it she not only proves that their mere presence helped increase Dickinson’s writing by relieving her of household work, but that they may have even inspired some of her unusual syntax through the Hiberno-English dialect.

Both the Maher and Kelly families were post-famine immigrants, arriving in the US around 1854-55. Both were from Slievenamon (in Irish, Sliabh na mBan, meaning the mountain of the women) in South Tipperary, which was bilingual until very late in the 19th century. Murray describes the Mahers as “moving up in the world”: “The poorest people couldn’t get beyond New York and the neighborhoods near the docks in Boston, but they made it all the way to Amherst. After the famine, the families who did survive made economic gains, and the Mahers did. They were definitely on firmer ground right before they emigrated.” The Kellys were less well off and did a “chain migration,” sending members of the family over one by one as they raised the money. Though they moved up and down the east coast, both families ended up in Amherst where many other Irish had found work.

Over the years, Dickinson had employed several Irish servants, beginning in 1851 with Rosina Mack. Next came Margaret O’Brien, a maid who stayed with the Dickinson household until 1865. Searching for someone with a “mediating effect” on her family life and writing, Dickinson finally employed Margaret Maher, whose arrival changed the course of Dickinson’s writing. Not only did Dickinson write in the kitchen while cooking with Maher, she trusted her with her poems. “Dickinson starts storing her poems in her maid’s trunk, the one she brought over from Ireland. It’s still in the family,” says Murray. “That always gets Irish people going ‘Whoa!’ and I think Dickinson kind of knew it. The one [trunk] that comes bobbing across the sea…she didn’t travel broadly but decided to put the poems in the trunk that had been across the Atlantic and up and down the eastern seaboard with Margaret Maher.” They also shared writing to some degree – Maher came from “a locus of literary interest and the home most famously of writer Charles Kickham” in South Tipperary and spent her life around people who wrote. Although sparingly, Margaret also wrote creatively, and Dickinson would often respond to these short letters or poems with her own poetry, creating a bond of words between the two women.

As she gets older and more into her vocation as a writer in the later 1860s, she’s not associating with her peers – the white wealthy – she’s associating with the people in the kitchen, and more and more of them are Irish.”

Shockingly, Dickinson told Maher to destroy the poems upon her death. While her sister Lavinia burned Dickinson’s correspondence, Maher found that she could not bring herself to destroy Dickinson’s lifetime of work. In tears, she brought the poems to Dickinson’s brother who agreed that they should be saved. Maher also saved one of the few pictures we have of Emily Dickinson today, a daguerreotype that the family had discarded earlier.

Murray describes these borderline miraculous events as “material,” focusing instead of the creative impact Maher and the other servants may have had on Dickinson. “Dickinson was very attuned to languages,” says Murray. “Not just Irish but a lot of them. When she was a teen, she was really into Robert Burns – he uses a lot of that Lowlands Scottish vernacular as part of his poetry. She adores him – she goes around the house talking this way. So she’s really into that and I like to think of this in terms of continuity. As she gets older and more into her vocation as a writer in the later 1860s, she’s not associating with her peers – the white wealthy – she’s associating with the people in the kitchen, and more and more of them are Irish.” The most potent draw in the kitchen is Margaret Maher, who Murray describes as “quite a force.” While we cannot draw definite conclusions about the influence of Irish language on Dickinson’s writing, Murray points out that Maher was possibly bilingual (her letters seem to suggest this with her overuse of the dative) and that Hiberno-English made its way into some of Dickinson’s poems. As an example, Murray points to the use of “himself” in “Silence is all we dread”:

Silence is all we dread.

There’s ransom in a Voice—

But Silence is Infinity.

Himself have not a face.

Murray also considers Dickinson’s attitude towards death, which was macabre compared to the consolation poetry of the time. “When I think of ‘I Heard a Fly Buzz When I Died’ I think of the whole Irish sense of the grotesque with death. I don’t think she was ever in a wake house but I think it’s like the Irish take on death – laughing death down. She may have arrived on it independently but there is a similarity,” she says.

Upon her death, rather than having her family and close friends as pallbearers, Dickinson planned for six Irishmen – all former employees – to carry her casket. They carried her out the back door of the Dickinson residence, used primarily by the employees of the household.

For Irish Americans, Murray’s research for Maid as Muse reveals yet another exciting example of the incalculable influence that famine and post-famine immigrants had on the shaping of American literature, history and culture. For everyone who has ever read a Dickinson poem, this work, in the words of Dickinson scholar Martha Nell Smith, “represents a sea change.” Not only will researchers approach their understanding of Dickinson in a different way, museums are now changing their exhibits to reflect new discoveries. In the past Murray has given tours of the Dickinson Museum with current housekeepers and gardeners on the property. Now she’s thinking about how to integrate the servants’ stories into an exhibit at the New York Botanical Garden in April. A third-generation Irish American on both sides (her father’s grandparents are from Cork), Maid as Muse has given Murray the opportunity to insert herself into a “literary lineage” that is well-worn but still open to interpretation. “More people who walk through [the exhibit] can relate to the servants because that’s mostly our story,” Murray says. It’s the immigrant story. So Dickinson becomes more human; she becomes more fully realized.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June / July 2010 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply