The following commentaries, from writers, politicians, actors, activists, artists and business people, culled from 25 years in Irish America, offer unique, personal perspectives on the starvation of our forefathers.

Peggy Noonan, author and political commentator, interview, July/August 1990

“The first time I ever went back to Ireland, I met a very old man named Paddy Kennedy, who as a little boy had grown up with my mother’s father. He was so excited when I came to see him that he poured me a glass of whiskey and we sat and drank the whiskey and he told me about the day my grandfather left Ireland. My great-grandfather walked my grandfather down to the end of the road where he was to be picked up and taken to a train. And my great-grandfather put his hand on grandpa’s shoulder and shook his hand, didn’t kiss, didn’t embrace — very Irish. Shook his hand and said, ‘Go now and never come back to hungry Ireland.’ A whole class, a whole race of people, who thought it was finished where they came from. And who had — luckily for the American gene pool — enough grit and optimism and wit to come here.”

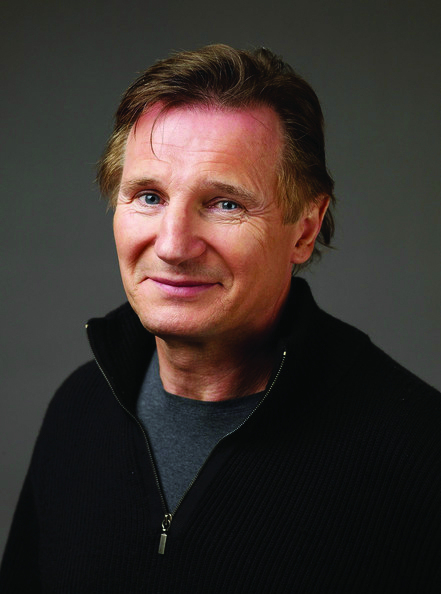

Liam Neeson in a speech accepting the American Ireland Fund’s Heritage Award, January/February 1996

“…thousands of my fellow countrymen came to this country with only the clothes on their back and an average life expectancy when they got here of six years. America has given a lot to the Irish. The Irish have given a lot to America as an immigrant population. We have worked hard, and thrived in industry, commerce, government and the arts.”

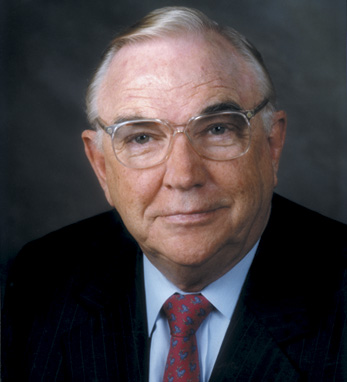

Tip O’Neill, interview, October 1998

“In 1845 my grandfather Patrick O’Neill, then only 13, was brought to this country with his three brothers to work with the New England Brick Company. In 1856, at the age of 24, he returned to Ireland, married Julia Fox from his hometown and ten years later they came back to America.…Growing up as a youngster you were instilled with three things. The first was the “No Irish Need Apply” signs and what those signs were doing to the Irish, the second was the way your fathers came over here – off Famine ships – and you thanked God they were able to work to provide for their families. I thought of my poor great-grandmother, for instance, seeing her three boys, including my grandfather, leave, thinking she would never see them again.”

Robert Lyons, Kennebunkport, Maine, letter to the editor, March/April 1997

“My great-grandparents witnessed food riots with loss of life when the 1st Royal Dragoons fired into the hungry crowd September 29, 1845 in the seaport town of Dungarvan as “steely ships” sailed away with good Irish corn and oats.”

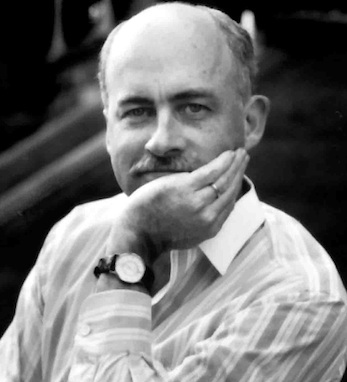

Andrew Greeley, interview, June 1986

“I think most Irish Catholics in this country are only dimly aware of the Famine. I often wonder how many of the Famine Irish survived. The death rates were appallingly high. The people who died on ships; the diptheria epidemics; the cholera epidemics. You go to cemeteries and you see a lot of graves of the young…My grandparents all came in the 1870s and 1880s after the so-called little Famine. Our family memories are not of Famine but the memories of growing up poor. It’s a typical American story. We grew up poor but we made it.”

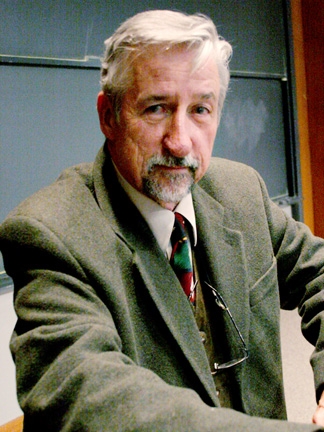

Thomas Keneally, interviews, July/August 1991 and March/April 1997

“You can’t acknowledge something as massive as the Famine followed by the evictions, cheating people out of their land and so on. It’s too massive to encompass, and so I think revisionism is a response. It astounds me as an outsider to read history that seems to blame the Famine on the exuberance of either the Irish or the potato. The potato is that well known exuberant, volatile plant, and the cause of the Famine. And it’s the fault of the Irish for being eight million instead of a more manageable population. It’s a little bit like blaming the Jews for the Holocaust.”

“… It’s never ceased to fascinate me since I was a kid that Ireland is the only nation in Europe whose population is roughly a bit more than half of what it was in 1841. In 1841 the population was 8.2 million, now it’s about five million. Between the 1830s and the 1880s, by which time the last of the Fenians had escaped from Australia or been liberated, you had a halving of Ireland. I think that created a culture of loss in Ireland and I think Ireland, in a sense, is a traumatized nation, the way the Jews are a traumatized people.”

Fionnuala Flanagan, interview, January/February 1997

“There is a whole school of thought that regards the Irish Famine as genocide, and there are arguments that can be legitimately made for that under the United Nations Charter, and it’s only now beginning to be examined. …

“The inherited legacy of colonialism includes this internalization of shame and the inability to deal with it so we just pass it on to the next generation. … I think poets and artists have always been aware of that.”

Joe Biden, interview, April 1987

“My mother’s maiden name was Finnegan; I believe her family was from Mayo. She was one of five children. Her grandfather and grandmother on both sides of the family were 100 percent Irish. The Finnegans came over after the first Famine, around 1845. The other members of the extended family all came in that period through to about 1880.”

Donald Keough, CEO Coca-Cola Company, interview, December 1989

“As a typical American with Irish heritage, my roots are a little fuzzy. The precise time of emigration I’m not certain of – my guess is that it was during or near the Famine. I’m quite certain the family came from Wexford. The name has different forms, as you know – Keough, Keogh, Kehoe – a lot of it was Anglicized spelling by authorities. The family settles in Massachusetts, near Pittsfield, and right after the Civil War, my great-grandfather moved out to the Midwest. He and a group of Irishmen went out to homestead land in Northwest Iowa near Sioux City, close to a little village called Maurice, where I was baptized. They homesteaded the land through some very tough Iowa winters, and created some wonderful farmland, in the tradition of many Irishmen who were interested in farming.”

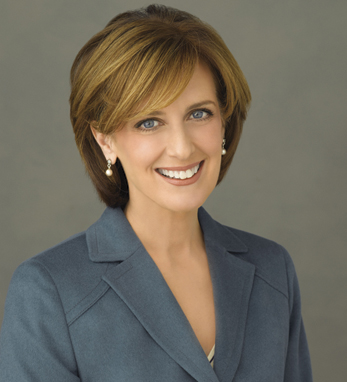

Anne Sweeney, President of the Disney Channel, interview, November/December 1997

“[My father’s grandfather came to New York from Mayo during Famine times] as a young teenager when he got off the boat with his brother and sister. And my mother’s family has a similar story. Very young people traveling without parents. They got here and fortunately the family structure was strong enough that it helped them survive and succeed.”

New York Governor George Pataki on the introduction of the Famine into school curriculum, November/December 1996

“All students will learn that, while there was a potato blight, the British exported food out of Ireland, out of the mouths of two million starving Irish men, women and children. History teaches us the Great Hunger was not the result of a massive failure of the Irish potato crop but rather was the result of a deliberate campaign by the British to deny the Irish people the food they needed to survive.”

Glenna Goodacre, designer of Philadelphia Famine Memorial, feature article, April/May 2000

“The tragedy of An Ghorta Mór contrasts with the outstanding achievements and contributions of Irish Americans and provides me with a unique opportunity to capture the range of human experience.”

Patricia Harty, speaking at the U.S.-Ireland forum, New York, February/March 2008

“Do you know about Grosse Ile? It’s an island in the St. Lawrence River in Canada where thousands of Irish are buried in mass graves. Estimates are that one in seven famine immigrants never [survived the journey]. And that their life span was seven to fourteen years if they did. All we ever learned in Ireland was they got on the coffin ships. We didn’t learn what happened to them once they got here. It is my dream that Ireland, the mother country, would care enough to know what happened to her children, and teach that history in the schools. Terry Dolan [Professor, School of English, University College Dublin] talked about a building and how many stories there are in a building. There are enough stories in Irish America to fill a very tall building.”

Thomas J. Flatley, real estate developer who emigrated from Kiltimagh, Co. Mayo in 1950, March/April 1997

“My grandfather Ambrose O’Brien, born in 1840, lived through the Famine and was a Fenian who worked closely with Michael Davitt on land reform. My mother, born in 1891, often spoke to me about the Famine, about how Mayo was one of the hardest hit countries. I believe strongly that I have benefited from those Irish who came to Boston and struggled before me. When I arrived here in 1950, I was able to find a level playing field in the business world largely thanks to their efforts.”

Senator George Mitchell, former marine senator and peacemaker for Northern Ireland, interview, May/June 1995

“Grosse Ile was a place that led to the original Irish settlement in Maine in the 1830s. There was a downturn in the Irish economy in 1829 and 1830, often called the small famine, and a lot of them came over and landed on Grosse Ile. They had no means of transport and so they walked to the United States and they walked through Maine. There was a lot of violence along the Maine border in 1830, and a number of them stayed in Maine, in fact, there was quite a substantial settlement, while many more went o to Boston. So I’m quite familiar with Grosse Ile. It led to the first large wave of Irish immigration in Maine.”

Excerpt from a letter from British Prime Minister Tony Blair on the 150th anniversary of the Famine, which stopped short of formally apologizing for Britain’s role in the Famine, but remarked on the failure of the British government to properly address the developing tragedy. – IA report on the 150th anniversary commemoration, which took place in Cork. July/August 1997

“The Famine was a defining event in the history of Britain and Ireland. It has left deep scars… [It] is something that still causes pain as we reflect on it today. Those who governed in London at the time failed their people through standing by while an op failure turned into a massive tragedy. We must not forget such a dreadful event. It is also right that we should pay tribute to the ways in which the Irish people have triumphed in the face of this catastrophe.”

Rudy Giuliani, former mayor of New York City. IA feature: October/November 2002

“One hundred and fifty years [after the Famine], the spirit of the Irish people was the backbone which America relied upon during the worst attack in our nation’s history.”

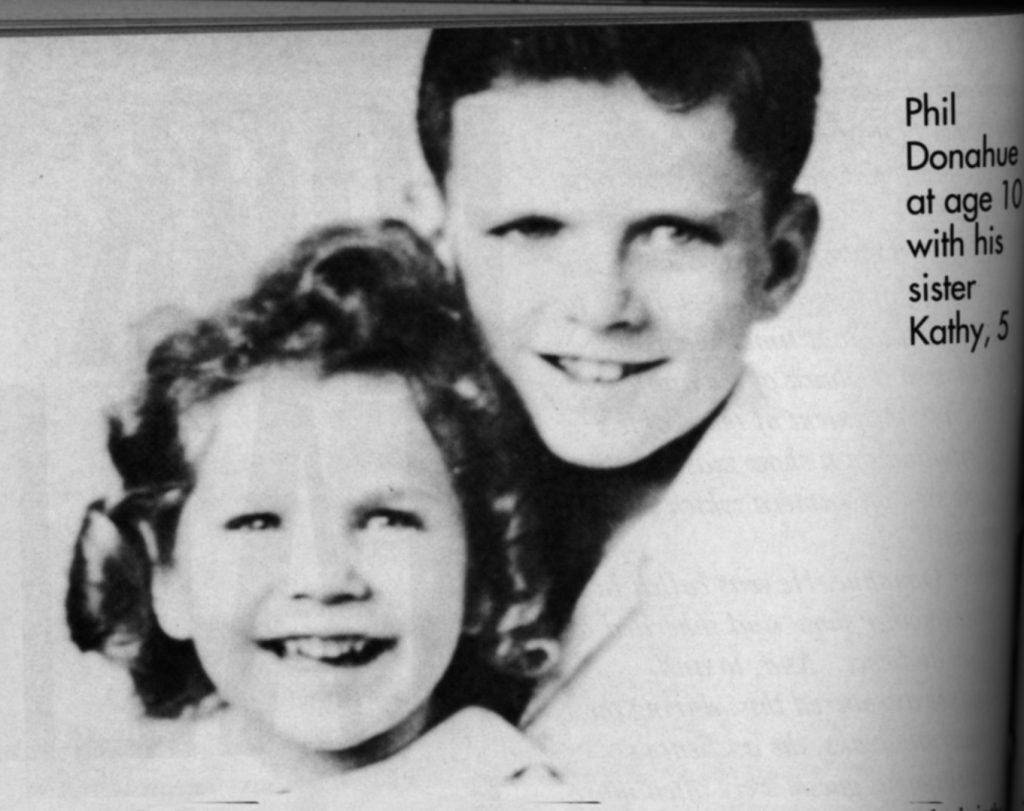

Phil Donahue, talk show host, interview, October 1990

“I am tempted to conclude that we might be potato famine Irish immigrants. It’s certainly clear that going back to my grandparents, I may be third or even fourth generation American. … I have no memories of a prejudice because of my identity – a position no doubt earned for me by the broken heads of my Irish ancestors in the labor movement and other places. Nobody ever called me a Papist or a Harp. I’m a very lucky guy having been raised in what I perceived at the time as a mainstream ethnic and religious identity.”

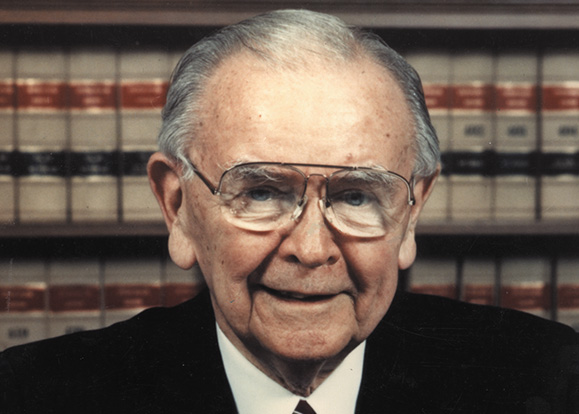

William Brennan, Supreme Court Justice, interview, June 1990

“My father’s family consisted of two sisters, Catherine and Winifred, and two brothers, Patrick and Thomas, as they all – I don’t know what years, but shortly after my father – left, and in my mother’s family, her aunt was already here. You know how terrible things were [in Ireland] then? I would suppose, if there were any kind of work at all, that they would have taken the chance. But they saw a chance for a better life in America. That’s what I think. I don’t know all the details – neither mother nor father talked about it that much.”

Peter Quinn, author, interview, December/January 2009

“We take so much for granted: Our ancestors came over and built all these schools, churches, hospitals, the unions, the Democratic party—a whole world. But they had to build it all from nothing. There were a lot of reasons why they should have fallen apart or just disappeared. You know, if it were just a matter of skin complexion they could have become Protestants, but something deeper and more complex was going on.” …

“There’s a line by Samuel Eliot Morison in the Oxford History of the United States, published in 1961, I believe, that I read in high school. It said, ‘The Famine Irish made surprisingly little contribution to the economics or culture.’ Yet look at popular entertainment: They made a tremendous contribution, beginning with the minstrels theater and traveling shows. And the economic contribution—who does Morison think dug the canals, the reservoir; who dug the Erie Canal? Yet a leading American historian could write that the Irish almost didn’t exist.”

Senator Tom Hayden in a letter to Irish America, February/March 1999

“Why the Irish starved is a question for students and historians to examine. Was it British indifference, racism, religious bigotry, laissez-faire economics, poverty, overpopulation, or other factors? Those are legitimate questions, but to simply delete the colonial dimension and describe Ireland as a sort of hardscrabble environment is intellectually outrageous. … The impact of this misleading history is to reinforce images of the Irish as a helpless people whose suffering was caused by fate, images which surface again and again in contemporary society.”

President William Jefferson Clinton on the 15th Anniversary of the Famine, reported in July/August 1997

“Perhaps the haunting memory of the Famine helps to explain the remarkable generosity of Irish people across the world. [The Famine was the greatest disaster in history of Ireland, but out of that tragedy emerged a blessing for our nation, the men, women and children who crossed the ocean to build new lives in America.”

Bruce Morrison, former congressman and sponsor of the Immigration Act of 1990 which allotted 48,000 “Morrison Visas” to the Irish. Feature article, February/March 2008

“We need Irish and Americans to learn a lot from each other and the immigration heritage, what it’s about and how to react to it and be smart about it. If we think about the relationship between Ireland and the United States [with respect to our current immigration question] and Ireland’s relationship to the world in terms of its immigration [practice] then what you want for the future will tell you how to fix the mistakes of the past.”

Thomas Cahill, interview, March/April 1996

“There’s a lot of, I think, sadly, negative self-images, to use modern jargon, amongst the Irish. They internalize what the British thought of them. It took a long time. It didn’t happen immediately. And I think without the Famine it might never have happened. It took the disaster of the Famine for those negative self-images to really take hold.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 2010 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply