The Deadly Trail that Finally Revealed a Phantom Branch of My Family Tree

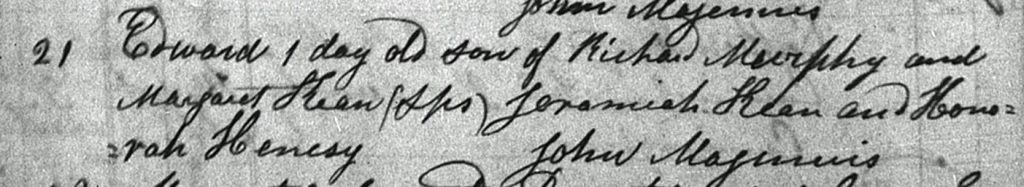

My earliest American-born ancestor was my great-great-grandfather, Edward Murphy. It took a while to figure this out as the skimpy traces he left claimed both New York and Ireland as his birthplace, but then I stumbled across his baptism. To my delight, he was christened in the historic St. James church in Manhattan not long after it opened in 1836 — the 175th child in the register.

I had long known about Edward’s sister, Hanora “Nora” Murphy who married a man named John Nelligan, but he also had two brothers — John and William — who remained a mystery. Since Murphy is the most common Irish surname, both of them became lost in an ocean of John and Williams Murphys as soon as they left home.

It didn’t help that this portion of my family had scattered. Most worked on the Erie Railroad, so many migrated from Piermont, New York to Jersey City, New Jersey when the terminus moved south, but others went elsewhere. Massachusetts, Illinois, and Brooklyn, New York all came into play, meaning that even if John and William had survived childhood and stayed close to some pocket of the family, I had a handful of cities in four states to wade through Murphys in.

As a professional genealogist, I’m always busy researching other people’s families, but recently, I grabbed an opportunity to tackle this nagging gap in my own. I began by reacquainting myself with records retrieved decades ago, and after just a few minutes, did a double take.

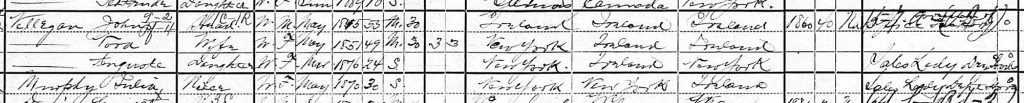

The 1900 census for Edward’s sister, Nora (Murphy) Nelligan, showed her in Chicago, Illinois with her husband, daughter, and 30-year-old niece, Julia Murphy. Huh. Edward didn’t have any daughters of this name, so unless this was a niece through her husband, Julia must have been a daughter of either John or William. I berated myself for failing to notice this before, but swiftly resolved to be grateful for this clue and see where it might lead.

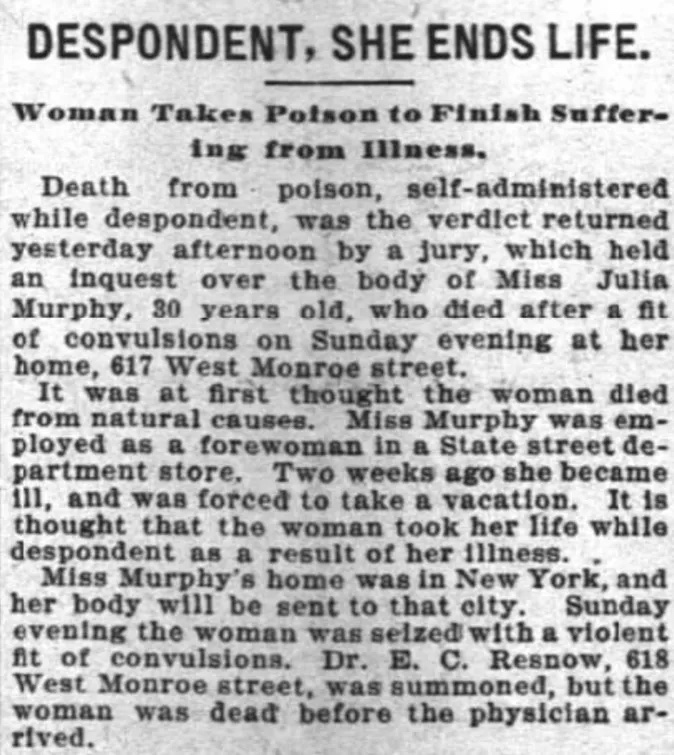

Hoping that she could lead me to her father, I followed Julia’s trail — and that’s when I got blindsided. Three years later, she had apparently committed suicide.

The 1900 census for Edward’s sister, Nora (Murphy) Nelligan, showed her in Chicago, Illinois with her husband, daughter, and 30-year-old niece, Julia Murphy. Huh. Edward didn’t have any daughters of this name, so unless this was a niece through her husband, Julia must have been a daughter of either John or William. I berated myself for failing to notice this before, but swiftly resolved to be grateful for this clue and see where it might lead.

Hoping that she could lead me to her father, I followed Julia’s trail — and that’s when I got blindsided. Three years later, she had apparently committed suicide.

It was a strange story, and as I write these words, I’m waiting for a copy of the coroner’s report to see if it offers any clarity, but Julia supposedly poisoned herself because she couldn’t cope with an illness that had overtaken her. I was crestfallen as she had struck me as strong and independent. Not many unmarried women at the time would have picked up, moved almost 800 miles, and secured a job as a forewoman at a department store.

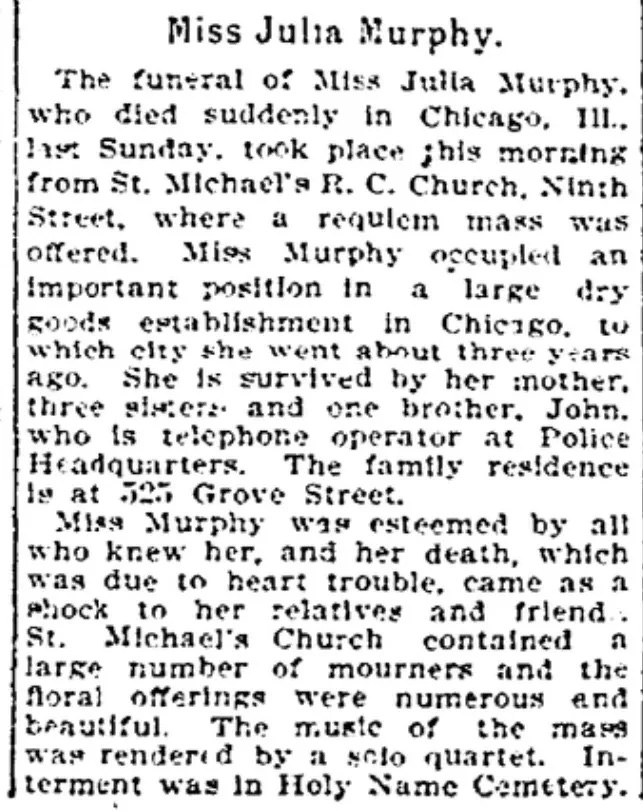

It’s a somewhat twisted reality, though, that an ancestor’s misfortune often generates a series of breadcrumbs for today’s genealogist to track. So yes, it was helpful that one of the articles I found about Julia stated that she was from New York and her body was being sent there. This prompted me to look for corresponding pieces in New York newspapers, a search that came up empty, but I had better luck across the Hudson in Jersey City where an obituary lamenting her “heart trouble” had been published. It also said that she was being buried in Holy Name Cemetery and was survived by her mother, three sisters, and a brother, John, who was a telephone operator at police headquarters. This was familiar territory as Jersey City features prominently in my family history, but it didn’t answer my question about her father.

The mention of a brother John working with the police rang a bell as I recalled such a fellow being cited as a nephew in other obituaries I had tripped across over the years. This hadn’t been sufficient to gain traction previously, but now I knew I was on the hunt for a John who had at least four sisters, one of whom was Julia.

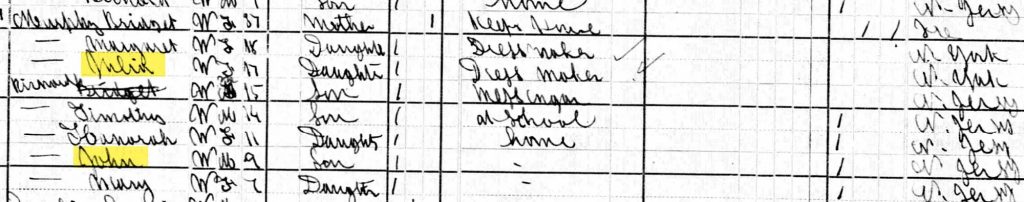

The 1880 census in Jersey City popped up a possible family, but with no father, a Julia who was seven years older than expected, and other details — such as one child being corrected from Bridget to Richard — that raised questions. Then again, the older children had been born in New York and the younger in New Jersey, a pattern I was accustomed to thanks to the Piermont to Jersey City pipeline, so maybe this was the right family. I turned next to the 1885 New Jersey state census.

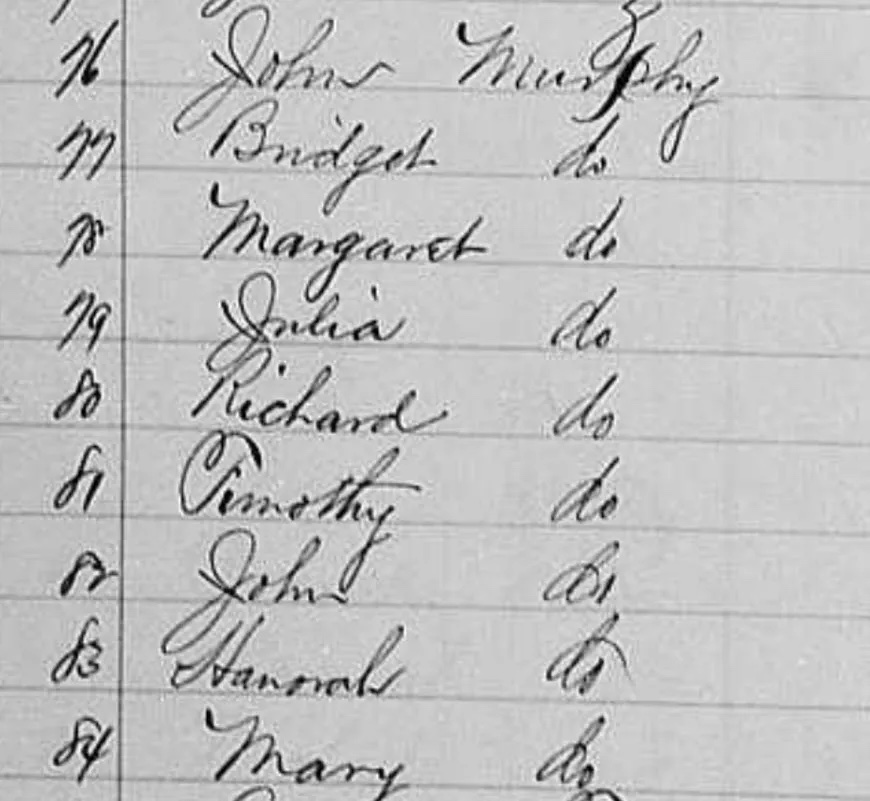

Here was the family again, but this time with a father. I had been hoping for John or William, so was very pleased to see John. It could have been anything else, so this alone was a big step in the right direction. And since Irish men often named their first-born sons after their fathers, it was promising that the oldest boy was Richard — the same as Edward, John, and William’s father.

Seeking further substantiation, I reviewed baptism transcriptions on FindMyPast and Ancestry and was encouraged to find that the older children were christened in St. John’s in Piermont and the younger in Jersey City churches. Julia, it turned out, was born in 1863 so had lopped about seven years off her age when she got a bit older.

The seven siblings were the offspring of John Murphy and Bridget Crimmins, a couple who had married in Piermont in 1861, so all the pieces were fitting, but I was confused about John. Why was he with his family in 1885, but not in 1880? Maybe cemetery records would help me understand.

Recognizing it was an iffy prospect, I returned my attention to Julia to look for her burial. As a Catholic, I was aware that someone who committed suicide before the 1980s — much less back in 1903 — would have been barred from being laid to rest in consecrated ground, but given that Jersey City papers covered her passing differently than Chicago ones, it seemed worth checking. Perhaps her family had refused to accept the verdict or somehow worked around the church’s restrictions, and if so, more power to them.

Yes, there was Julia in Holy Name Cemetery — better yet, with 12 others in the same plot. I exhaled on her behalf and scanned the ten Murphys, two Skidmores, and one Murray and all buried together. Comparing names and dates, and detouring to other records to explain the non-Murphys, it was possible to confirm that this was the same family in the 1880 and 1885 censuses. I was increasingly optimistic that this was the mystery branch that had evaded me for so long, but to be sure, I’d have to determine what had become of John.

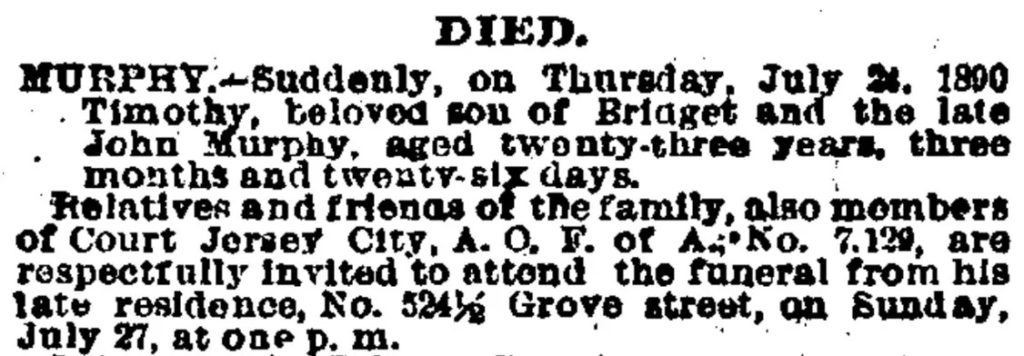

Sure, there were two John Murphys, but one — the police-affiliated one — lived until 1920. The other passed away in 1896, but there were no traces in New York or New Jersey to explain his presence in the grave site. I’d noticed that Timothy was interred the same day, so was anticipating an article about an accident of some sort — the kind of event almost guaranteed to make the news — but found nothing.

But wait a minute. What if they didn’t die then, but instead, were placed in the family plot that day for a different reason? I eye-balled the other dates. The only one that preceded the Timothy-John pairing was Richard’s four months earlier. Could it be that the family was finally able to purchase their own plot and had Timothy and John moved from elsewhere to rejoin the family? I had encountered this situation before.

The Holy Name database I accessed is online, but long before it existed, volunteers at the Hudson County Genealogical & Historical Society (HCGHS) had already indexed a good portion. Having seen images of the cemetery’s burial cards in the past, I knew that they sometimes contained more snippets of information, so wondered whether there might be any more useful tidbits in HCGHS’s version. And there was — an age column. Timothy was said to be 24 when he breathed his last and John was 30.

Timothy was born in March of 1866, so 24 meant he would have died around 1890. Newspapers disclosed no feasible candidates, but sometimes you have to trick OCR-based collections into discovering their own content, so I experimented. John’s wife, Bridget, used the phrase son or daughter “of Bridget and the late John Murphy” in death notices for a couple of their children in later years, so I tried this phrase and was able to surface his obituary.

If the same age-based logic that worked for Timothy applied to John, I should expect to find his death around 1868, but he was in the 1870 census, so something was off. And if he had died as early as 1870 or so, why was he recorded with his family in 1885?

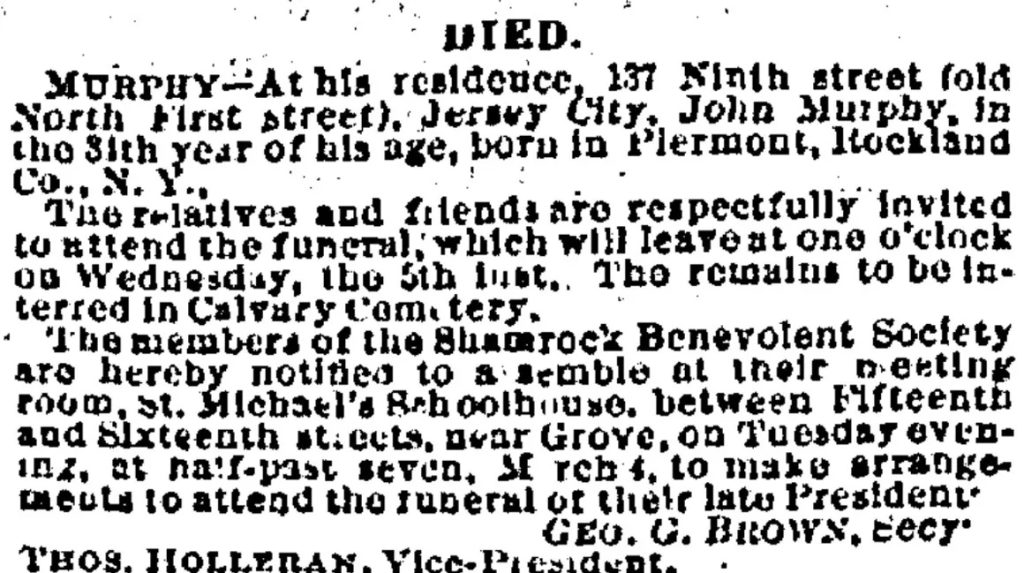

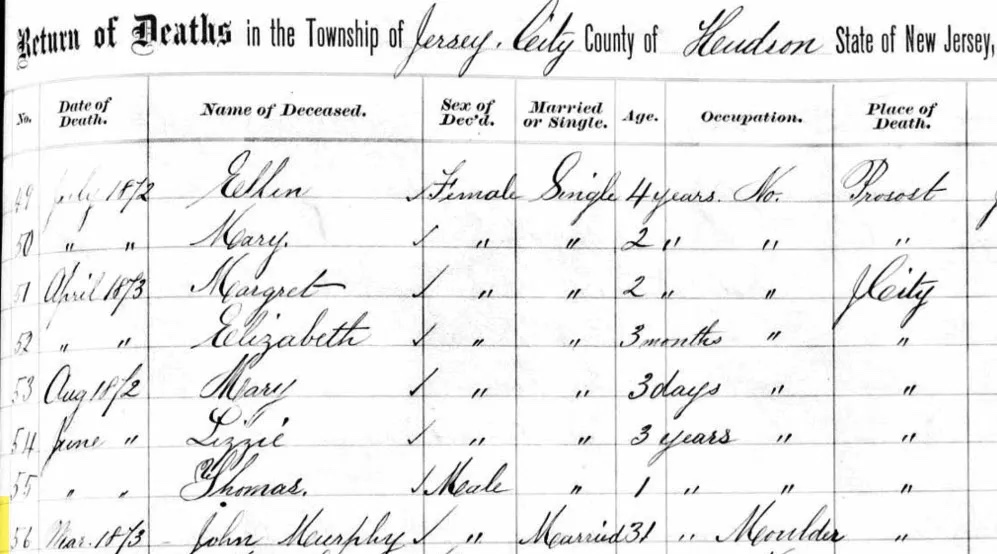

In spite of my confusion, I decided to inspect city directories for the 1870ish time frame for a John and Bridget Murphy couple that seemed to fit. It didn’t take long to turn up a Bridget, widow of John, residing at 137 Ninth with her occupation noted as “liquors.” Backing up a few years, I spotted a John Murphy, whose livelihood wavered between liquors and moulder, living at 109 N First. Iron work was common in my family and both Murphys had worked in liquors. This John appeared up to 1872 while the widow emerged in 1874. I wished the addresses had been the same, but she could have moved, and enough of the other details dovetailed that I thought this could be the John I was seeking and that 1873 was my target date.

Given the prevalence of his name and the limits of OCR, I searched online newspapers for both addresses in the relevant time period and eventually unearthed his obituary. The funeral announcement obligingly mentioned that this John Murphy had been born in Piermont, so I was confident he was the right man. I also learned that the family had stayed in the same place, but the street names had changed, removing my lingering doubt about the different addresses.

Now equipped with a narrow date range, I found him in New Jersey death index. While I had come across several possibilities during an earlier attempt, “my” John had been masked by a mistranscription of “Meurphy,” a good reminder that even surnames as simple as Murphy can get distorted.

I was both intrigued and relieved that John’s obituary described him as the “late president” of the Shamrock Benevolent Society (SBS). The relief stemmed from my awareness that his 30-year-old, Irish-born widow had been left alone with seven children ranging from eight months to 11 years — precisely the kind of situation the society would have stepped in to help with. Further sleuthing revealed that John had established the Jersey City chapter in 1866, Bridget was licensed to run a restaurant, and the SBS continued meeting there after John’s demise. I was grateful they had rewarded his initiative by watching after his family.

The final surprise was that he had been taken to Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York. Sure, it was a likely place for a Catholic in the vicinity, but all the branches of my Irish American family had used Holy Name in Jersey City for generations. Maybe his position with the SBS played a role? After all, they had presumably covered the cost.

Regardless, this explained the tardy Holy Name burial date. 1896 must have been when they disinterred him so he could be with the rest of his family. It dawned on me that I now had two fresh avenues to chase, starting with Calvary.

Calvary Cemetery is delightfully old school. Even in 2024, you call to inquire about your family, so I did. My hope was to obtain names of other family members — his missing brother, William, for example — entombed with him. But no such luck. They had his file, but he had been on his own, Bridget had purchased the plot, and it had been re-sold soon after he was removed. Ah, well. It didn’t hurt to try.

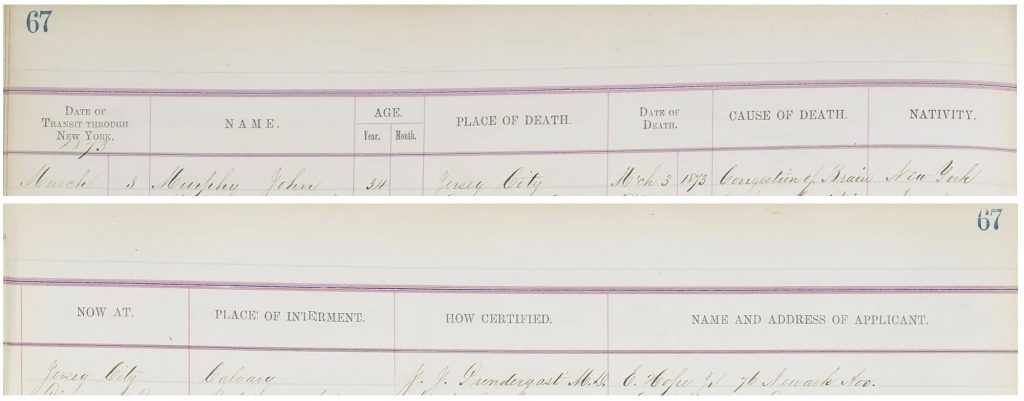

As to the other option, I welcome any excuse to play with under-the-radar resources so Bodies in Transit immediately jumped to mind, and yes, it’s what you probably guessed — a collection of “bound volumes recording the transportation of bodies in, out, and through Manhattan during 1859–1894.” Since John’s transfer took place in 1896, the 1894 cutoff made me wince until I remembered that he had to be taken to New York in the first place back in 1873. I could have browsed by date, but happened to know of an index created by the German Genealogy Group, so looked up the “reel” and image number, and there he was.

Curiously, this document logged John’s exact date of death and his correct age of 34, making it the most accurate of the paperwork associated with his decease, so it was well worth obtaining and free as well.

There was no denying that my elusive relative, John Murphy, had perished in 1873, his short life span contributing to the difficulty of tracing him. His being listed with his family in 1885 had injected an impediment, but I can only guess that it was because they missed him and even a dozen years after his loss, considered him the head of the family.

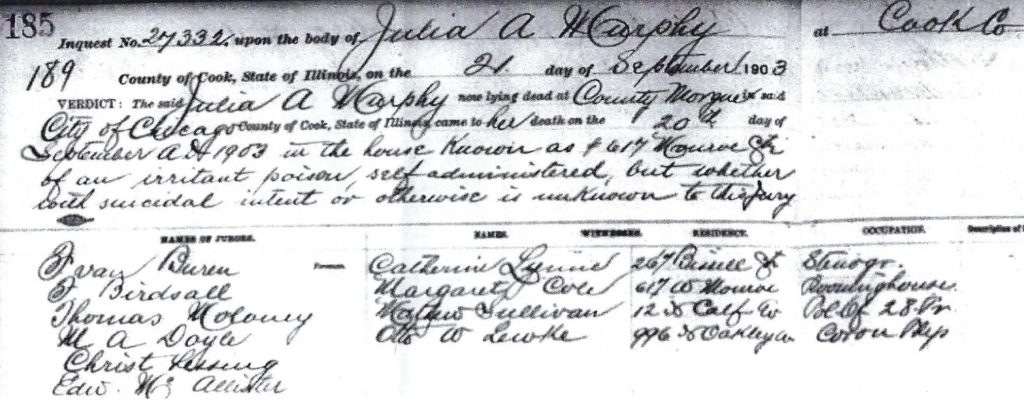

And what about Julia who had pulled me into this tunnel of research in the first place? As I was winding up, the mail arrived (the result of another transaction with a pick-up-the-phone repository) with the coroner’s inquest. Julia succumbed to “of an irritant poison, self-administered, but whether with suicidal intent or otherwise is unknown to this jury.”

So the Chicago newspapers that had reported her “suicide” had touted a claim not supported by the coroner’s jury. This was the moment that Bridget came into sharp focus.

Someone had made sure that Julia would not be denied a proper burial in spite of the sensational reporting that accompanied her loss. Someone had troubled to keep John’s memory alive in the 1885 census. Someone had gone to the effort of having him disinterred 23 years after his passing. I took a closer look at the list of those in the plot, and realized that someone had ensured that Mom, Dad, and all seven of their children would rest together in eternity. And most of the paper trail I had followed to uncover this missing branch of my family tree owed its existence to that same someone — Bridget (Crimmins) Murphy.

Bridget left us 99 years ago, but in her honor, I’d be grateful if you’d spare a thought for her and any Bridgets you might be fortunate enough to have in your own family. Go raibh maith agat. ♦

About the author: Genealogist Megan Smolenyak is a real life history detective who loves to solve mysteries. You might have spotted Megan or her handiwork on Top Chef, Who Do You Think You Are?, Finding Your Roots, Faces of America, Good Morning America, the Today Show, The Early Show, CNN, PBS and NPR.

Her news-making discoveries include uncovering Michelle Obama’s family tree, revealing the true story of Annie Moore, the first immigrant through Ellis Island, and tracing President Barack Obama’s roots to Moneygall, Ireland, and Vice President Joe Biden’s roots to Mayo and Louth.

Formerly Chief Family Historian for Ancestry.com, she also founded Unclaimed Persons.

Megan is the author of six books, including Hey, America, Your Roots Are Showing and Who Do You Think You Are? (companion to the TV series), and conducts forensic research for the Army, BIA, coroners, NCIS, and the FBI.

Megan is all Irish on her mother’s side, with roots in Cork, Kerry, Longford, Leitrim, and Antri

Leave a Reply