“How can you help writing about something you feel intensely?”

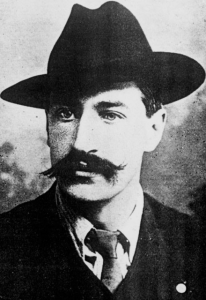

Ireland may have more poets than any other Western nation, but Lola Ridge remains in absentia on lists of Irish poets. True, most of her life was lived outside Ireland but she held her Irish heritage close, believing she was of royal Irish blood, the Reillys of Loughrea, County Galway a “very old race of kings.” She was born Rose Emily Ridge in Dublin in 1873.

When she was 13, her mother took her to New Zealand where Lola grew up in mining towns, and 8 years later, married Peter Webster, a gold mine manager and alcoholic. She left the failing marriage and, taking their son, Keith, moved to Sydney to study and write. Although she won first prize in a national poetry contest, she realized Australia’s Bush wasn’t a place for a flourishing poet and traveled to the other side of the world, San Francisco, where her work immediately found a publisher.

Always determined to reject Victorian moralism and embrace total freedom, she re-invented herself: Rose Emily Ridge became Lola Ridge and then, shockingly, put her 8-year-old son in a Los Angeles orphanage not reuniting with him for six years (She would be the first to admit she was “not nice.”). She moved to New York City—Greenwich Village, of course—where she presented herself as a modernist poet, labor activist, and anarchist. Her transformation became complete when she lopped 10 years off of her age.

In New York, Lola supported herself by working as both a model and a factory worker. The publication of her free-verse imagist poems, The Ghetto, a sympathetic portrayal of Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side, brought Lola success and recognition.

The Ghetto

They are covering up the pushcarts…

Now all have gone save an old man with mirrors–

Little oval mirrors like tiny pools.

He shuffles up a darkened street

And the moon burnishes his mirrors till they shine like phosphorus…

The moon like a skull,

Staring out of eyeless sockets at the old men trundling home the pushcarts.

At the time of The Ghetto’s release, she gave Modernism its voice proclaiming, “Let anything that burns you come out whether it be propaganda or not … How can you not write about something you feel intensely?” As the editor of two major Modernist magazines, she became the center of the avant-garde in New York; Lola’s trajectory from a New Zealand wife and mother to a New York radical was complete.

Blithely committing bigamy, she married fellow leftist, the much younger David Laws in 1919 and the two lived a life of deliberate poverty in a cold-water apartment. Despite the shabby digs, Lola hosted salons for poets, writers, critics, and artists. The loft, often compared to a Dublin tenement, was wind-swept, barely furnished, and freezing. Fellow poets in attendance were Ezra Pound, Marianne Moore, and Hart Crane but she especially championed Jean Toomer of the Harlem Renaissance believing he was the true representative of American Modernism. Other writers and social activists joined the poets and Lola, a charismatic hostess, led the discussion about the future of art in America.

Always a woman of political passion, she became the proletarian poet of class conflict, joining picket lines, protests, and labor rallies. She wrote stirring poems about lynching and especially, executions. In 1927 she was arrested, beside Dorothy Parker and Edna St Vincent Millay, for protesting the execution of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti. The experience inspired a profound poem, Electrocution, still relevant today.

Electrocution

He shudders. . . feeling on the shaved spot

The probing wind, that stabs him to a thought

Of storm-drenched fields in a white foam of light,

And roads of his hill-town that leap to sight

Like threads of tortured silver. . . while the guards—

Monstrous deft dolls that move as on a string,

In wonted haste to finish with this thing,

Turn faces blanker than asphalted yards.

They heard the shriek that tore out of its sheath

But as a feeble moan. . . yet dared not breathe,

Who stared there at him, arching—like a tree

When the winds wrench it and the earth holds tight—

Whose soul, expanding in white agony,

Had fused in flaming circuit with the night.

But Ireland was always on her mind. She paid homage to the Easter Rising with The Tidings, a poem written while she was organizing for fellow anarchist Emma Goldman.

The Tidings

My heart is like a lover foiled

By a broken stair –

They are fighting to-night

in Sackville Street,

And I am not there!

In Sun-up and Other Poems (1920), she celebrated the Irish activist Jim Larkin, who was arrested in the Palmer raids on an extended visit to the U.S., was jailed in Sing Sing for anarchism, and sometimes visited by Charlie Chaplin.

To Larkin

One hundred million men and women

go inevitably about their affairs…

They do not see you go by their windows, Jim Larkin,

with your eyes bloody as the sunset

And your shadow gaunt upon the sky…

You, and the like of you, that life

Is crushing for their frantic wines.

In her later years, she won a Guggenheim Fellowship, traveled to Baghdad and Mexico – and took a young lover at age sixty-one. In 1936, watching a parade in

Mexico City, she raised her fist in solidarity with the marching Communists. Still, she was always sickly, once inspiring her best friend to snark, “she’s Brunhilde of the sick bed.” Toward the end of her life, she underwent a spiritual revival; her last poem was addressed to a divine power: “In thy high company—/ whereof all things are free.”

Penniless, anorexic, and addicted to the migraine suppressant Gynergen, she died of pulmonary tuberculosis on May 19, 1941, in her home in Brooklyn, at the age of 67. Her obituary in the New York Times celebrated her as “one of the most important poets in America” and even that stately paper carried on her pretension, printing her age as 57 and not 67.

Lola and her work fell into obscurity after World War II, a victim of the prevailing anti-liberal bias. But today she and her work are being rediscovered—Maybe she’ll even make the lists of Irish Poets. ♦

Leave a Reply