On August 9th, 2014, one of the most chillingly iconic photographs of the 21st century was published online. The memory of it still sends a pour of cold along my spine. The orange jumpsuit. The black balaclava. The line between desert and sky. The knife was held casually by the executioner’s thigh. The portent. And then – in later images taken from a video still – the eerie, almost unbelievable, image of a young man with his head resting on his back.

It was a photograph that was shown around the world and shook our collective souls.

An American journalist, Jim Foley, was the first of several hostages to be killed in an onslaught of public barbarity by ISIS, a jihadist group that was still relatively unknown at the time. The presence of the photos and the video on the internet somehow twisted the knife further. The image was propelled into inboxes all around the world and the dark edges of the web displayed a sort of perverse schadenfreude.

So often we become what we don’t want to admit. The image was profoundly disturbing and confusing, yet compelling. Look, don’t look. Death was a click of the keyboard away.

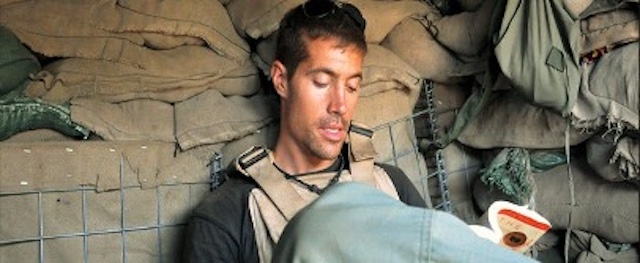

Later that same day, amidst all the lingering horror, another very different image landed in my inbox, sent to me by a friend. A handsome young man sat in a sandbagged bunker. He wore a flak jacket and jeans. He was deeply tanned, with a strong jaw, slightly unshaven. Everything about the photo exuded calm and control. He read a paperback book with a red band across the top of the cover.

There are moments when the bird hits the windowpane. The thud of surprise.

In an instant, the photo, and the reason my friend sent it, made sense. I sat there, stunned, gazing at the computer screen. Jim Foley had been pictured – some time, some place — reading a copy of a novel I had written, Let the Great World Spin. I closed the image and then opened it again as if to check the authenticity.

I felt a surge of kinship with him. We were, in a way, sharing words. One story grazing another. Except those words had been taken and he had been decapitated. All language, gone.

Shortly afterwards I decided to write to his mother, Diane Foley. I found her address and sent an email suggesting that I would be willing to help write her son’s story, or indeed her own if ever the opportunity happened to arise. The weeks and months passed until, almost a year later, I heard that she had signed a contract to write her own book. There was the answer, I thought. Leave well enough alone. She was more than capable of telling her own story.

Fast forward six years. I had written a novel, Apeirogon, set in the Middle East. The novel didn’t have any direct reference to Jim Foley, but I did feel that he had, in a tangential way, inspired me toward the book: his bunker photo had been on my wall all those years. In the course of a Zoom call for a book group at Marquette University (Jim’s alma mater), I mentioned that I had tried to be in touch with Diane and that I was still intensely touched by the photograph of her son reading. Incredibly, Diane was on the Zoom call. An hour later my inbox pinged. She told me that she had never seen my mail. In the years after, she had tried to write her own story but for a variety of reasons she had never been able.

I suggested that I would drive from my home in New York to New Hampshire, where I could sit with her and her husband, and perhaps operate as a “story whisperer.” I thought I might maybe be able to help thaw some of that frozen sea that she, as a mother and a storyteller, had experienced.

Her husband, John, said that I reminded them of their son Jim. I slept in a room where a few of Jim’s old possessions surrounded me.

At the end of two days, I was astonished to find out that two of their son’s killers – the infamous Beatles — had been captured in Syria, stripped of their British citizenship, and brought to the U.S. to face charges of conspiracy to torture and murder. One of them, Alexanda Kotey, had copped a plea. Part of his plea was that he would talk to the victims and/or the victim’s families.

And so began a year-long project where I would help Diane tell her story. Always, at the front of my mind lay the photos. But both images had been burned on my retina. In one, the desert, the orange, the knife, the killing sands. In the other, the one tacked onto my office wall, a man reading in a bunker.

But photos, like stories, seldom end. Their echoes extend. We are propelled forward by mystery. Both Diane and I often wondered where the image had been taken and who the photographer had been. I had researched it online but couldn’t find a clue.

And then one night, just last November, Diane and I attended a concert for the non-profit global storytelling organization, Narrative 4, in New York. Onstage was Sting singing “The Empty Chair,” his tribute to her son Jim. Behind Sting, the bunker photograph was projected on a giant screen. A small gasp went up from someone in the audience. They recognized that photo. Their cousin had taken it.

Yet another windowpane.

“Yeah, I took that photo,” said Bill Wilder, when I called him a few days later. He had been a machine gunner with the 101st Airborne in the Kunar Province of Afghanistan. “We were in an outpost called Pride Rock. Way up there. We didn’t know a reporter was coming. We weren’t sure what to think about a guy being embedded with us. But Jim was from New Hampshire, like me. And we hit it off. We knew some of the same people. He was very cool, very calm. Ballsy too. He asked a lot of tough questions.

“He sat with me in my bunker. I was manning a 50 caliber. The bunker is the sleeping area. Sometimes it got loud, I mean really loud. But Jim was down there, just reading that book. I couldn’t believe it. Jim was the sort of guy who went where the action was. There had been a bunch of drawdowns. ‘Get your helmet on, man,’ I told him. And later he just went back to the book. I couldn’t believe he was reading through the chaos. I told him that he couldn’t be Mister Shadow Man, behind the camera all the time. So, in a quiet moment, I picked up his camera and took the photo.”

Now, ten years after his death, Jim Foley’s shadow extends in a kaleidoscope of directions. He is remembered as a fearless reporter. His memory evokes the power of nuanced storytelling in an age diseased by certainty. Diane has created the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation to advocate for other hostages and to help bolster the safety of journalists all around the world. And Jim, against all the evidence, has become a symbol of hope.

His image remains seared on our collective retinas — not so much as the man kneeling in the desert, but as the storyteller in a permanent act of composition. ♦

American Mother by Colum McCann with Diane Foley will be published on March 4, 2024, by Etruscan Press. McCann and Foley will be appearing in the Irish Arts Center (NY) on March 6, 2024, at Harvard Bookstore in Boston on March 7, 2024, and in Philadelphia (with Sting) on March 9, 2024.

The book is currently available for pre-order on Amazon in Kindle or Hardcover formats.

Leave a Reply