Thirty-one years ago, I walked up to an apartment in north London to meet one of my heroes, Shane MacGowan. He was asleep when I got there and drunk when he woke up, funny, shy, and acerbic. He cut off one of my questions to tell an unprintable story about the Jam’s lead singer, Paul Weller, leant his sister fifty quid, which he pulled out of a pocket amidst a large clump of notes, half of which fell slowly to the floor as his manager and I watched, drank and laughed his slow-motion, eyes-wide laugh. Sometimes he seemed to forget I was there. I walked out an hour or so later, wondering how such a person came to be. The genius, and he clearly was a genius, was easy to understand, the person far less so.

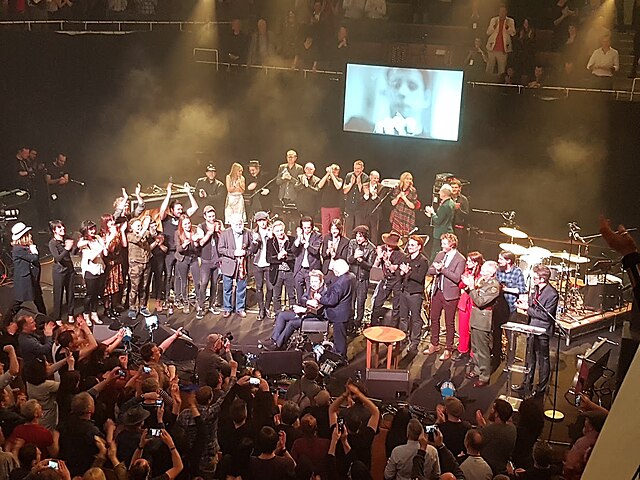

On the occasion of MacGowan’s death, here is the unpublished interview. A day after his death, I thought of what the actor Ossie Davis said of Malcolm X. “He was our manhood, our living, black manhood.” I feel the same way about MacGowan, in an Irish context. He was our living, breathing, Irish manhood. We’ll never see his like again. – Stephan Talty

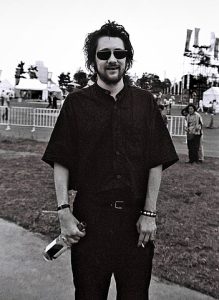

London 1992

It is a unique feature of a Shane MacGowan concert that as soon as he walks on stage, the crowd not only shouts its welcome but attempts to guess just how drunk he is.

MacGowan is a legendary singer/songwriter in the Irish tradition and a legendary self-destructionist, also in the Irish tradition.

Those two facts have always been linked, but recently drinking nearly ended MacGowan’s career.

The Pogues, the band he founded ten years ago, kicked him out of the group last year, and alcohol was one of the root causes of the breakup. So when MacGowan began his solo comeback with four nights at New York’s Bang On! club this fall, all eyes were on his eyes.

Everyone agreed it began badly. As he came on stage the first night, MacGowan bobbed his head and blinked rapidly like a man desperately trying to stay awake. His face was so completely without expression that it could have been staring out of a coffin, and his voice got lost in a murky sound mix.

Playing behind him were the Rogues, an American band styled after the Pogues that never really approaches the anarchic brilliance of their models.

MacGowan seemed to know this all too well. But as the band crashed out song after song, MacGowan lost his dead-man look and tore into the lyrics with his eyes flashing.

Half the crowd lifted into the air when he hit the choruses.

“Did you forget how to sing?” someone yelled sarcastically at the beginning.

Somehow, actually, he hadn’t.

At points in his career, MacGowan has resembled the father of all Irish drinking myths. But it is clear that without the life he has led, there would not have been the music that led Joe Strummer of the Clash to call him one of the two or three greatest songwriters of the century. As he prepared for his comeback from his London flat, MacGowan talked about liquor, Tipperary, and the rest of it.

The flat sits in a raw workingman’s neighborhood in north London. The floor is covered with videos, playing cards, wrappers, dice, figurines, empty checkbooks, children’s toy figures, and cassettes, all covered with varying layers of dust. In the middle, like a mountain dominating a squalid landscape, sits a mound of cigarette ashes two inches high.

MacGowan sits on the couch, asleep. “We’ll wake him in a minute,” whispers his manager.

MacGowan founded The Pogues one night at a London club when he began to play Irish rebel songs at breakneck speed and with the rage and exhilaration of his heroes, the Sex Pistols.

The British soldiers in the audience replied by whipping their fish and Chips at his head. But against the wispy synthesizers of Culture Club and the other bands of the early 80’s, MacGowan and his mates had raised the ghosts of punk and of romantic Ireland.

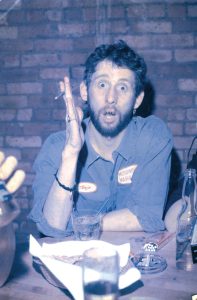

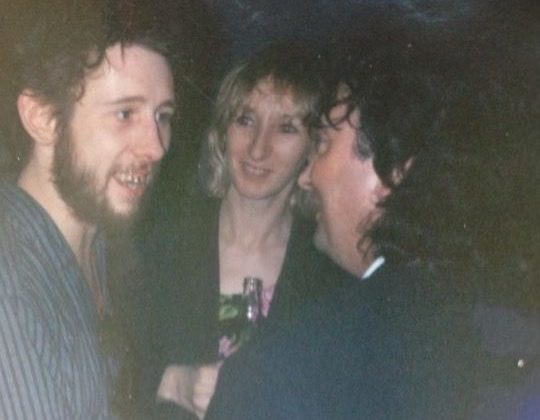

MacGowan wakes up and his huge, pale blue eyes instantly transform his face. His younger sister, Siobhan, who has her own band in Dublin, joins him on the couch and he begins to talk about Ireland in his blurred London drawl.

“As a child, I loved Ireland and haaaa-ted England,” he says.

“I hated England because it’s a boring, ——up, miserable place, y’know?”

Tipperary, in southern Ireland, was where he was happy. He was “a bit of a brat, “ a good Catholic and precocious. By seven, he wanted to be an author and was reading Joyce, Behan, Dostoevsky, James Baldwin. “And William Burroughs!” he says, laughing in his trademark slow-motion rasp.

His mother and her family were traditional Irish musicians, “locally famous.”

His father didn’t work regularly but wrote fiction and what Siobhan describes as “sardonic” poetry, which he never published. “But he can write very tender stuff as well,” MacGowan says. “It was gre-eaat stuff!”

Siobhan nods. Like everyone now around MacGowan, she seems devoted to and a bit intimidated by her mercurial and needful brother.

When MacGowan was six, the family settled in London. MacGowan claims to have had his first drink (Guinness) at six, and to have had his last extended period of sobriety at 14. It was then he was kicked out of a prestigious English public school for selling drugs (Was he guilty? “Na-oohh.” Pause. “I made some money, though.”)

By this time, he had stopped reading and writing fiction. “I started living,” he says.

MacGowan’s voice drops and he leans off the couch for emphasis, his eyes enormous and clear. “And I did live.”

The life MacGowan led would be familiar to many teenagers who later burst on England as the punks. “I was doing drugs by then,” he says.

“Most nights I stayed out all night. I would stay out, sleeping rough or whatever, with my mates for a five or six-day binge. Then I would crawl home and fall over, turn Jimi Hendrix on real loud, know what I mean?”

When he was 16, MacGowan was put into a mental hospital to get off the Valium a doctor had prescribed.

Unsure why he had been committed, and in a cell between a junkie “screaming for his fix” and a man reliving in his nightmares his mother’s death, MacGowan went cold with terror.

He seems deeply marked by those nights.

“Seeing and hearing all that ——- horror and misery changed, a lot of things for me, right?” he said in 1989. “Taught me a lot.” In fact, that night contained most of the elements of a hard MacGowan lyric: imprisonment, insanity, junkies and fear.

When he was released in ’76, punk came and MacGowan “was one of the earliest in.” He became notorious for having part of an ear bitten off by his girlfriend at a Clash show, and he wrote and published a Clash fanzine. (“Others charged 10 pence because they did it for love of the music,” he says, displaying his last remaining copy of the fanzine. “I charged 30 because I wanted money.”)

Still, MacGowan says punk “blew my head apart, broadened my mind in a matter of weeks.”

MacGowan is not an easy man to work with. He sometimes would play deaf-mute for a day. Or pull a coat over his head for amusement. Or go AWOL from the band’s grueling touring and recording schedule. His legend grew quickly. Would he “do a Behan” and drink himself to death? Was he already brain-damaged? MacGowan never stopped drinking and spitting out predictions he would live to 88.

Despite the mayhem (or in MacGowan’s view, because of it) he produced. His songs are classically structured, and flawlessly tight. MacGowan credits their quality to obsessive re-editing, and a childhood spent in corners listening to his relatives play.

The best of MacGowan’s music is as sharply beautiful as anything in the great, abused tradition of the Celtic reel and ballad. But far, far wilder. “I think he’s a genius, actually,” said Chris Mundy, a writer at Rolling Stone. “He’s one of the only people who combines the pure assault of rock with this hopeless romanticism and these brilliant images.”

In MacGowan’s songs, barmen and sailors and punks crash their way through exuberant, damned lives. MacGowan laces the grubby and violent tales of street life with sudden appearances of angels and compassion. Catholic doom and beauty. “With incredible sadness, there’s sometimes intense Joy,” MacGowan says. “That’s just how I see life.”

The bitter lyric against the sweet tone, the combination of body-breaking hedonism and piercing beauty is something any Celt five hundred years ago would have recognized instantly* MacGowan agrees emphatically. “I’m not an original,” he says.

“I come from the Irish tradition. I write in the Irish tradition. And I follow it, rigidly.”

He goes on, for once not searching for words. “There was this ye-earning in me always to connect myself with the past, which I love very dearly, which is gone. This gloriously happy childhood in Ireland, like with the music and all the rest of it. And I thought I could connect myself with it and relive it to some extent through the music.”

“It worked,” says O’Hagan.

“Yeah, it wo-orked!” MacGowan says. “I don’t feel sad anymore. About not living in Ireland, I mean.” His longing for Ireland led MacGowan to what one critic called songs of “bruised reminiscence.” In one of the finest, a sweeping ballad called “The Broad Majestic Shannon,” MacGowan sings about a last parting by the river near where he was raised:

“The last time I saw you was down at the Greeks

There was whiskey on Sunday and tears on our cheeks

You sang me a song as pure as the breeze

Blowing up the road to Glenaveigh.”

MacGowan alternates between relief and bitterness when talking about being kicked out of the band he created such music with. “I’d lost interest in the Pogues three years previously,” he says. “I wanted to play Pogues music, the music we started with.”

His voice grows bitter, disgusted. “And they wanted to play psychedelic Jingle-jangle, bloo-dy house party music. Because they were selfish, and I was unselfish, I let them destroy the bloody group.”

Asked what his hopes are for the next ten years, MacGowan repeats “ambitions?” as if he had never heard the word before.

What about hopes? “HOPES?” he asks harshly. Then he mutters, “I think they would be unprintable.”

His manager, Paul Rowan, jumps in, “Y’know, write some great songs and have a good time.

“Write good stuff, have a good time playing music, and don’t ever get caught up in that bloody music industry trap I’ve been caught in all these years,” MacGowan says. Now working on a solo album, which he describes as being close to the spirit of the early Pogues, MacGowan says he will never play with the band again. They remain friends.

Some have accused MacGowan of following his heroes, Jimi Hendrix and especially Brendan Behan, into an early grave. For the moment though, MacGowan seems attached to life and his work in a way that Behan, at his lonely and pathetic end, was not.

MacGowan’s deep dives into the bottle are rooted not in Irish literary history, but in a childhood that ended harshly and fast.

In fact, there is a great deal of the brilliant child still in MacGowan. When he discovers a cassette with striking liner notes lying on the couch, he cries “WA-OOOOWW” over and over as if it were a beautiful gift. He is cared for by his friends, with whom he shares his good fortune, and only occasionally bullies them.

When he tells a story about Tipperary, he acts out each part in hilarious back-country Irish voices. He regularly passes money to the drunks that he nearly joined on the London streets.

His views on the world are far from child like, and often display a fine black wit. “I don’t take drugs to torment myself,” he once said. “I’ve got life to do that for me!” But when it comes to the future, and what he wants out of it, MacGowan sits on the couch and stares down silently at the cluttered floor. Finally, O’Hagan speaks up. “Stay free?” he says, naming the title of an early Clash song. MacGowan looks up. “Yeah,” he says in a clear voice, “Stay free.” ♦

Stephan Talty is the award-winning author of Agent Garbo, Empire of Blue Water, and other best-selling works of narrative nonfiction. His books have been made into two films, the Oscar-winning Captain Phillips and Only the Brave. He’s also the author of two psychological thrillers, including the NYTimes bestseller Black Irish, set in his hometown of Buffalo, NY. Learn more about Stephen by visiting, stephantalty.com.

So grateful to be able to read this. Thank you so much for acknowledging this late hero of mine. It’s beautiful and I’m saving the article bc it’s highly touching to read.

I love you Shane.