It is somehow fitting that the Good Friday peace agreement of 1998 has become inseparable from Irish poetry. If, for a moment in Northern Ireland, “hope and history rhymed” or those involved in resolving the conflict “walked on air against their better judgment,” phrases that politicians and other speechifiers ubiquitously quoted, they had poet Seamus Heaney to thank for their grab-bag of memorable phrases.

Last April, politicians, activists, scholars, and students from throughout Northern Ireland, gathered at Queens University in Belfast 25 years on, to examine the peace agreement’s successes and failures. It was as if the old peace-process band had gotten back together. Over the three days of the conference attendees heard from former President Bill Clinton, former Prime Minister Tony Blair, former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams, founder of the Women’s Coalition Monica McWilliams as well as Unionist leaders, and former Irish and British diplomats.

While the early enthusiasm and optimism of the peace agreement have given way to the dreary recriminations of polarized politics, Seamus Heaney’s spirit and words were invoked by a number of participants. Bill Clinton, frustrated by the shuttering of the Northern Ireland Assembly, told a packed auditorium that rather than still walking on air, they now had a “hard floor” of political institutions to walk on. Raising a finger in the air, he added that they should, “For God’s sake, get up and walk.”

Heaney, who died ten years ago on August 30, insisted that a poem “never stopped a tank.” Yet, Heaney insisted that literature and poetry could contain an “answering energy” that drives what writers and poets do that is not entirely socially impotent.

After three days in Belfast, I drove to Dublin to talk in more depth about Heaney and other Irish poets, James Joyce, and the complexities of Irish nationalism with Declan Kiberd, one of Ireland’s foremost literary scholars. Kiberd has thoughtfully explored the ways in which the nation of Ireland was written into existence through novels, poems, and drama. If Ireland has become, in Kiberd’s description, “a quilt of many patches and colors,” it is writers who have helped knit that quilt.

In Kiberd’s monumental book Inventing Ireland, he showed how writers have constantly renovated Irish consciousness and by doing so transformed the country’s cultural, social, and political life. Of particular interest for Kiberd is how artists have prefigured a future where the “either or polarities” that restrict identity, politics, and life are punctuated.

I talked to Kiberd in Dublin across from Merrion Square in his office where Daniel O’Connell had once lived. Kiberd, who has held many academic positions, is currently a Professor of English and Irish Language and Literature at the University of Notre Dame’s program in Dublin.

In the lower room of the Georgian building, we sat underneath bookcases of hundreds of books by and about Heaney that had been translated into what looked like 20 or so languages. Kiberd compared Heaney to Yeats, pointing out that they both were writing in “occupied spaces, controlled by an outside power,” a situation that could drive a writer to turn inward. While Heaney came from a Catholic background and understood intimately the oppression and discrimination they experienced, Kiberd pointed out that Heaney’s “cause was poetry,” not nationalism. “Rather than become a gunman, he thought of himself using words as weapons of a disarmed people,” Kiberd said.

In his poem ‘Digging,’ Heaney makes what Kiberd refers to as the “connection between violence and social ritual,” explicit. In the opening lines, the poet’s “squat pen rests; snug as a gun” between his finger and thumb. A poem ostensibly about the rhythms and sounds of his father digging potatoes ends up with Heaney pushing “down and down for the good turf” and for the depths of creativity. It is the squat pen that Heaney will dig with, forgoing propaganda and political causes for art.

One of the themes that Kiberd and I talked about was the way that memory, history, ritual, and culture are preserved in some fashion but also transformed over time. One of my favorite Irish plays is Brian Friel’s Translations, which I saw over ten times when Irish friends of mine were performing at the Celtic Arts Center in Los Angeles during the early 1990s. It’s a drama about language, colonialism, the traumas of change, and how for some people, ancient myths are more vivid than reality.

I asked Kiberd what he made of one of the key lines from the play: “To remember everything is a form of madness,” and how the mural images that I had recently seen on the “peace walls” in Belfast seemed to be part of a psychic repetition compulsion that gets played out in the stalemate of real-world politics.

A central “anti-nostalgic” theme of Translations, is that at some point we are all required, despite the difficulty or pain, to face the facts in front of us. In his book Inventing Ireland, Kiberd points out that despite the presence in the play of strong characters who are “dreamers” – Jimmy Jack, for instance, believes he is going to marry the Goddess Athene – “the pragmatists outnumber the dreamers when the chips are down.”

“In the North today,” Kiberd said, “both sides hold on to versions of the past. I think it has to do with a sense of threatened identity.” Friel knew, he added, that ancient cultural forms are eventually translated into alternative configurations; Irish into English, dogmatic Catholicism into Celticized à la carte spiritualism, and hard-core nationalism into a more congenial civic republicanism.

Kiberd worries about what happens to societies that move from deep ritual to routine but insists that what Heaney referred to as “the low-key consolations of the quotidian,” is where you might find intimations of the marvelous. One way of throwing yourself into the path of the everyday extraordinary is, as James Joyce knew, through walking.

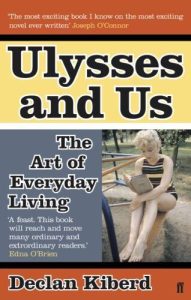

My favorite book of Kiberd’s is Ulysses and Us – The Art of Everyday Life in Joyce’s Masterpiece, which tracks the chapters in Ulysses through thematic congruences – Waking, Learning, Eating, Wandering, Loving – with an eye towards opening up the difficult text to regular readers. If the “experts,” the “Joyceans,” have dominated commentary and scholarship on Ulysses, Kiberd wants to show how a regular person’s “daily rounds,” might be “open to serendipity,” through the lived wisdom that people can discover on the streets.

In Ulysses and Us, Kiberd describes how Joyce celebrates, through his character Leopold Bloom’s walk across Dublin, the “random, uncontrollable circulation of bodies through the streets.” By walking, Kiberd said during our discussion, “People could feel the beauty of circulation of blood in the body. Joyce thought the circulation of bodies in the city was a sign of civic life and was a real recovery of freedom for most ordinary people.”

Of particular interest to Kiberd is how Bloom moving through the city is not a linear process but more like the process of reading Ulysses, of feeling lost in a labyrinth of language and meaning. Thematic potentials are cut short, mistakes of identity abound and there are confusing leads and wasted time. The “surface calm,” Kiberd writes, “is deceptive.” Bloom, like the reader, the critic or a journalist searching for the “truth,” is “anxious to decode the private signs all around.

As an American journalist working in Northern Ireland, I’ve often had that feeling of not quite knowing what is going on, an “outsider’s” lament. As much as I’ve read about the history and politics there, it always seemed like what was not being said was more important than the approved text or the official pronouncement.

Joyce’s biographer Richard Ellmann wrote that “Joyce practiced humility before the workings of the universe,” and that writing was also an act of liberation. In some sense, Joyce wrote in order to discover what was going on.

Kiberd believes that Dublin is still a great waking city while at the same time fearing that the celebration of Bloomsday might be a brief elegy for a lost city, bowler hats, and Bloomsday breakfasts before rushing off to their busy lives. He wonders how knowable Dublin still is.

Kiberd writes that there is something about the idea of “future narratives” as being “multi-plotted,” and therefore fluid with potential. That’s certainly the case with the Good Friday Agreement. At the Queens conference, the longest part of every speech was the obligatory thanking of everyone who had made the peace agreement possible. The list went on for minutes.

Years ago, I was told by a Loyalist leader near an interface area between the Falls Road and the Shankill Road that “good walls make good neighbors.” Perhaps so. But it struck me then as now, that the walls also restricted the ability of people to actually become neighbors.

Before I left Kiberd’s office he told me that Joyce would have been terrified by the idea of peace walls or partitions of any kind, preferring routes where people from different social and economic classes could meet and learn something of each other. “That was the kind of democracy Joyce stood for,” he said, “rejoining the sacred to the every day.”

Kiberd walked up three floors from his office to look at Brian Friel’s personal library, donated to Notre Dame in Dublin by Friel’s wife Anne after his death. Looking at the rows of books I told Kiberd that one of my other favorite plays of his was Wonderful Tennessee, which describes an island off the coast of Donegal shrouded in fog and mystery. The first line of the play is “Help! We’re lost! and the couples waiting for a boat to the island never make it.

I thanked Kiberd for showing me the library as I wondered how Friel transferred what he had read into his artistic work.

I told Kiberd I was now better prepared for a walk in Dublin, ready for my own mystery to unfold. ♦

Thank you! Wonderful and insightful article.

Rosemary Rogers