No Irish saint has been canonized for over 700 years – 1225 to 1975, Why?

The great St. Lawrence O’Toole was canonized by the Vatican in 1225, and there has been only one Irish saint, Oliver Plunkett, canonized since then, almost eight centuries – 766 years to be exact. It’s an extraordinary fact considering that Ireland, the land of “Saints and Scholars,” was arguably the most Catholic country in Europe. Over those seven centuries, the Irish suffered brutal colonization, poverty, and famines, including one that wiped out over a million of her people.

The famous Irish saints, Patrick, Columcille, Brigid et al, lived from the 4th to the 10th Century, the period of Celtic Christianity which folded pagan rituals into its customs, putting it in sync with Ireland’s ancient culture. Until the Vatican systemized saint-making in the late 12th Century, saints were holy folk who had developed a following, a cult that venerated them with shrines and prayers, and told stories of their wondrous lives and miracles. They were “saints by acclamation,” by “Vox Populii.”

Once Rome’s new saint policy went into effect, the first Irish saint to be canonized (1190) was the very eccentric Malachy O’More, an archbishop, prodigious miracle worker, exorcist, and self-styled prophet. End Time watchers look to Malachy’s “Doomsday Prophesy” which claims there will be 112 more popes before Judgment Day – our current pope, Francis, is said to be that number. The Church’s modern theologians dismiss this with “Non abbiamo bisogno” or “No thanks.”

The next Irish saint, Lawrence O’Toole, bishop of Dublin, ceaselessly and unsuccessfully tried to broker peace between Ireland and England, the only mediator trusted by both sides. His job was impossible – it was an English pope named Adrian who gave Ireland to England. When Lawrence died of a broken heart, it was becoming evident that Ireland was being marginalized by both England and Rome. His last words were in Irish, which translated, say, “Alas, you stupid, foolish people, what will you do now? Who will look after you in your misfortunes?”

Nobody, apparently. That question was answered in July 1690 when two kings met on the banks of the River Boyne. The Catholic king, James Stuart faced King William of England and Holland. The British won, the Irish lost, as the Protestant Ascendency began its rise with the dreaded Penal Laws not far behind. The Penal laws of 1695 seemed a personal vendetta against the Irish people sharing a bigotry and brutality that presaged the Gestapo, then centuries away. Catholics were forbidden to speak or read their own language (Irish Gaelic), vote, own land, study medicine, and law, join the army, own a horse or weapon. Even listening to Irish music was a crime.

Visiting Ireland at this time, the French philosopher, Montesquieu, observed it was such a debasement of the Irish people, indeed of human nature itself, that it must have been “conceived by demons, written in blood and registered in Hell.”

But what hit Ireland the hardest was the law that forbade the exercise of their religion and further deemed “A priest could be banned and hunted with bloodhounds” if caught saying mass. Catholics gathered in secret to attend mass, but soldiers, spies, and priest-hunters often found them and slaughtered congregants along with the priest, shades of Nero’s Rome. Where was their Martyr’s Crown?

Malachy and Lawrence squeaked by before the ‘No Irish saints need apply’ sign was posted. Not so lucky was Oliver Plunkett.

The Penal laws of 1695 seemed a personal vendetta against the Irish people sharing a bigotry and brutality that presaged the Gestapo, then centuries away.

Oliver Plunkett was a dedicated archbishop from Armagh during Penal Times, so he was forced into hiding to minister to his flock. In 1681 Oliver was accused of treason in the “Popish Plot” and “promoting the Roman faith.” He was brought to London for a sham trial. It took 15 minutes for the jury to declare him guilty, then much more time to have him tortured and drawn and quartered. And it took 316 years for the Vatican to reward his martyr’s death in 1975. Were they waiting for the dust to settle? Until his canonization, he languished as an ejaculation – short prayer – “Blessed Oliver Plunkett, pray for us.” His various body parts were spread over Ireland. He was the first new Irish saint in 700 years.

There was a Dutch priest working miracles in the Mt. Argus section of Dublin during the late 19th Century; he was known as Father Charles of Mt. Argus. His Passionist order was famous for preaching but alas, Father Charles’ command of English and Irish was sketchy at best but his reputation for healing even got him a nod in James Joyce’s Ulysses. He died in 1893, was beatified in 1988, and canonized in 2007. He was the last saint from Ireland to be canonized and he was Dutch!

John Henry Newman, educator, intellectual, and theologian was utterly and wholly British. He was born in London and educated at Oxford where he founded the Oxford Movement. He converted to Catholicism in 1845 and brought his fervor and faith with him when he went to Dublin in 1851. At that time Catholics were forbidden to attend secular or ‘Queens’ universities and from 1851 to 1858 Newman worked to establish the Catholic University of Ireland, later University College Dublin. Ireland likes to claim him as their own: Newman loved the Irish and the Irish loved Newman but he was British to the bone – Prince, now King, Charles even attended his canonization in 2019.

It was becoming obvious to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints that the small island off the coast of Northern Europe wasn’t a practical investment. It had no money, bad weather, and was always at odds with the powerful British Empire. While Vatican inbreeding may explain the excluding of this fervent Catholic country, it’s interesting to note that some questionable characters, self-promoting chancers from around Europe had been canonized during those 700 years.

Pope John Paul II, pope from 1978 to 2005, created 483 new saints over the course of his papacy, more than all previous popes combined. When he visited Ireland (the first pope to do so) millions of the faithful crowded into Dublin’s Phoenix Park to greet him. But despite Ireland’s worshipful welcome, it was still… non sanctorum in Hibernia. And while the saint-making process has never been allowed to begin until five years after death, Pope Benedict XVI waived the five-year requirement, effectively fast-tracking his predecessor’s canonization process. John Paul II was declared a saint a mere nine years after his death.

Those on the shortlist for sainthood are called “Blessed” and are close to the prize. Right now, the Vatican has shown uncharacteristic generosity toward Ireland as the list of Irish Blessed is quite large.

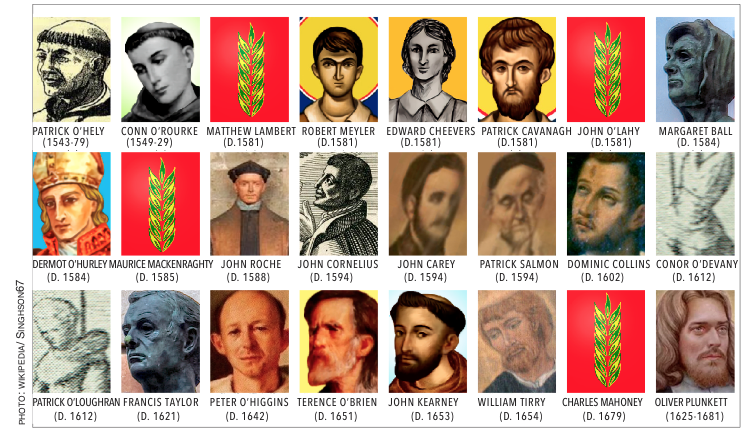

There is a sub-category, “The 17 Blessed Irish Martyrs,” and only one woman in the 17, Margaret Ball.

Margaret’s life was a Riches-to-Rags story. Her father, Nicholas Bermingham, originally from England, emigrated to Ireland, became a successful landowner in County Meath and an anti-Reformation activist. She married Benjamin Ball, an alderman whose wealthy family owned the bridge over River Dodder, giving the area its name, still in use, Ballsbridge. The couple and their many children moved to Dublin, spending time hosting and meeting those who could help further Benjamin’s political ambitions. It worked, Benjamin Ball became Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1553, and Margaret, the Lady Mayoress, became an elegant hostess and queen of Dublin society. Unfortunately for Margaret, another Queen, Elizabeth I, was also on the ascendancy.

Elizabeth I succeeded her Catholic sister, the despised Mary, who made the unwise decision to make Catholicism the state religion. Unlike Mary, Elizabeth wasn’t Catholic, but she was politically savvy, knowing that power rested with the rich Protestant noblemen who controlled Parliament. It helped that Elizabeth had inherited the rabidly anti-Catholic sentiments of her father, King Henry VIII, although she outdid him. He only created the Church of England, but Elizabeth, in 1559, made the monarch head of church and state and decreed her subjects to only worship at the Church of England.

By 1563, priests were forbidden to officiate or live in Dublin or the Pale. Margaret made a bold, courageous move – she turned her house into a safe house for Catholic clergy. Catholic laypeople were also subject to arrest, but Margaret was protected by her wealth and social prominence. She was not, however, protected from her eldest son, Walter.

“How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child!” (King Lear, Act I, Scene 4.)

In fact, Walter always identified with the British cause, his very name, “Walter” reeks of Protestantism and Elizabethan England. He happily and instantly renounced his Catholicism and signed the Oath of Supremacy, the “New Faith” being in alignment with his ambitions. Like his father, Walter became Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1580, and here the sharp serpent’s tooth comes into play: his first order of business was to have his mother arrested and paraded in a cart before all of Dublin. Getting even sharper, the tooth inspired the son to put his mum in the ratty basement of Dublin Castle, which served as her prison for five years. Walter refused to allow his siblings to feed her properly, and she spent the last years of her life in pain, dying in a rathole. Still, at her life’s end, she drew up her will and left her fortune, everything to Walter, proving once again the old adage, “There’s no Momma’s Boy like an Irish Momma’s boy.”

Currently, there are 28 Irish natives on the Blessed roster, only one step away from canonization. Here’s hoping. ♦

Leave a Reply