Q. What do Bob Marley and U2 have in Common?

A. Chris Blackwell

The founder of Island Records talks to Marilyn Cole Lownes about his Irish Jamaican heritage, U2, and his life in the music business.

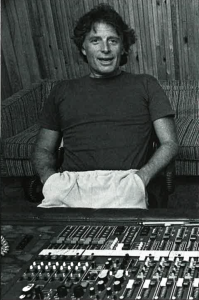

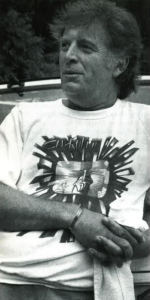

It’s no coincidence that the man who made Jamaican singer Bob Marley a cultural icon also made U2, the rock band from Dublin, an international phenomenon. Chris Blackwell, the founder and CEO of Island Records, is Jamaican and Irish. He is the music industry’s most laid-back guru, so laid back, in fact, that on the day we met in his London headquarters, he appeared in his “uniform” of jeans and flip-flops, borrowed some folding money from a willing member of his staff and whisked me off for a cuppa in his local care, or, as the English call it, “caff.”

“My father, Joseph Blackwell, came from the west coast of Ireland. His mother, my grandmother, was an O’Malley. The O’Malleys lived in a beautiful place called Clew Bay between Newport and Westport in County Mayo,” explains Blackwell.

What Blackwell started in Jamaica in 1958 was a small specialist ska record label, Island Records. It all mushroomed into a vast fortune later when he was able to sell his company to Polygram Records in 1989. Blackwell took home a reported 300 million dollars. Now, he is masterminding the launch of Palm Pictures, a new multimedia company in London. “The reason Palm Pictures is not Palm Records is that having founded Island Records in 1958, I didn’t want to start another record company. I’d been there and done that. I wanted to start something fresh.”

This philosophy has been the key to Blackwell’s success, putting him on the cutting edge, spotting trends, and backing hunches while marketing and promoting his discoveries with precision.

There is little that Blackwell, 60, still needs to do in the entertainment and leisure business. After building Island Records into the world’s largest independent record label, he diversified his interests into film, Island Pictures, also included in the package he sold to Polygram.

Blackwell remained a consultant until November 1997, when he finally severed all ties with his beloved company. By then, he had acquired land and property in Miami Beach, where he built hotels in the South Beach section first and then throughout the Caribbean. He called these hotels “outposts,” giving a hip, renegade flavor with a suggestion of “pushing the envelope” to his new global operations.

Chris’s first big international hit on his Island Records label in 1964 was singer Millie’s “My Boy Lollipop.” The acts he subsequently developed are a Who’s Who of pop music from progressive rock bands Traffic and Free and singer Cat Stevens in the late sixties, Bob Marley and Roxy Music in the seventies, U2 in the eighties, and the Cranberries and Pulp, now, in the nineties.

Considering his legendary business acumen, it’s startling and amusing to hear Blackwell admit that he can’t read a balance sheet. “I do not follow business plans; I’ve always followed my nose. I go in different directions; things guide me. I never did it for the money because I thought, `Hey, this is a good business; there’s big bucks here.’ I didn’t know, I loved the music so I did it. If you love something, you tend to go into it with passion and, then, you do it well, and the money just follows,” says Blackwell in his “outpost” in London’s Notting Hill, where he describes his staff as his “small guerrilla army.”

While he has homes worldwide – in Nassau, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Paris, Ireland, and London — Jamaica is his spiritual base. It also holds the key to Chris Blackwell himself, a man once memorably described as a “unique combination of insouciance, hustling and a love of Jamaican music for its `rebelliousness’ but who was born into the island’s beau monde, a world of extreme privilege.”

Chris’ father, Joseph Blackwell, related to the Crosse and Blackwell spice and sauce family, was a dashing young Irish Guards officer educated at the English “public” school Beaumont, near Windsor. He met and married Blanche Lindo in London in 1936. She was a beautiful socialite and Jamaican legend in her own right. “My mother’s family came to Jamaica in 1683,” he says with pride, “and it was her family land that Sir Noel Coward and Ian Fleming, both good personal friends, bought for their famous homes, ‘Firefly’ and ‘Goldeneye.’

“After my parents married, my father was transferred to the Jamaican Regiment, making it possible for him to help my mother run the family business of coconut and banana plantations,” explains Chris, a handsome man with chiseled features, blue eyes, and sandy hair coloring — not unlike that of Robert Redford.

Blackwell has been described by Nigel Dempster, in his London Daily Mail gossip column, as one of the ten most attractive men on the planet. Mix this with the easygoing charm of an old Harrovian, the casual outfit of jeans and flip-flops, and you have some understanding of people’s admiration for and fascination with Blackwell.

Unsurprisingly, Richard Branson, another public school dropout, cites Blackwell as his role model. Just his good looks and his ability to inhabit two worlds, lunching with JFK in Jamaica and then later in the day schmoozing with spliffed-out Rastafarians, hint at potent intrigue.

For someone without formal training in music, Blackwell attributes his extraordinary ear partly to his Dad. “As a child, I listened to classical music. My father loved opera — Verdi, Puccini, Wagner — or the instrumentals of Brahms and Strauss. He always played his records very loudly, never as background music, and he never played popular music.

My father was utterly Irish in his heart; he loved Ireland but came to love Jamaica, too.” Chris claims there is a particular affinity between the Irish and the Jamaican people. “They both innately love conversation, are poetic and talented.”

And, true to form, there was always a lot of conversation in the Blackwell house when Chris was growing up. “My parents loved parties. My father had lots of them. I remember being dragged downstairs to be introduced to and shown off to the seemingly endless lines of dinner guests, never less than fourteen every night.” The cast of these soirees could easily have been inspired by the song “Guess Who Was There!” As the song says, “Elsa and Cole, Tallulah and Noel…everybody was there.” Yet, it was just another boring dinner party for a young boy.

Nevertheless, Chris is proud today that he owns two “boring” guests’ Jamaican homes. Noel Coward’s Firefly, thanks to Chris, is now enjoyed by all as a museum filled with memorabilia, theater posters, and photos that commemorate the life of the noted playwright and author. And Ian Fleming’s ‘Goldeneye’ is kept as a deluxe villa rented by the likes of supermodel Kate Moss and her boyfriend Johnny Depp, actor Pierce Brosnan, and pop star Sting.

“My parents divorced in 1947 when I was ten. I don’t remember it being particularly painful in any way because, although I was very fond of my father, I didn’t get to see that much of him anyway as I was away at prep school in England.”

Blackwell’s ease with operating globally was enhanced when his father married an American lady and moved with her to Chicago, where Chris visited frequently.

“This was a fantastic thing for me because, until then, my life had been Jamaica to England, England to Jamaica. Suddenly America entered into the equation. And not New York or Los Angeles but middle America, the most cosmopolitan part of middle America, Chicago.

“I was very much part of that `American Graffiti’ era, the chicks and the cars, the jazz clubs – I loved it all, and I never felt intimidated by the U.S. the way some people are. I knew the vernacular and how it worked.”

When the family business began to founder in the early sixties, Blackwell moved to London to make his way.

“I started by importing ska and reggae tapes and records from Jamaica and sold them out of the back of my Mini-Cooper van in Brixton, where a lot of Jamaican émigrés lived. I figured that if I could sell 5,000 over the year, I could stay alive.” Jamaican music proved to be a gold mine when he started manufacturing records on his own Island label, selling to the fast-growing Afro-Caribbean population.

“Ska is an onomatopoeic word. It’s the sound of a guitar when it hits the off-beat,” explains Blackwell. “Jamaicans invented it sort of by accident when they tried to emulate the black music coming out of America at the time, particularly out of New Orleans. Fats Domino was a big influence, and it was the music initially based on the appeal of boogie-woogie on the piano. Ska evolved into `rock steady’, which was a slower beat, which in turn became reggae.

“Reggae has got that very infectious beat that we love because it’s recognizable and accessible, whereas calypso music is less so, even though that also has the Caribbean sound.” But, more significantly, reggae is a way for the roots people to express themselves, to get attention, and to get their points of view across to others. Remember, these people had no access to the media.

Blackwell is surprisingly quick and generous to point out that, although he gets the credit for Jamaican music’s popularity, the credit belongs to another man. “Studio One was the pioneering ska company founded by Dodd Coxson, who still lives in Brooklyn. It was Coxson who recorded a lot of Bob Marley songs before I got involved in 1972. It is Coxson who is the man really responsible for the fame of reggae, not me.” It was by sheer chance that Chris met Bob Marley at all.

“Bob had gone to Sweden to do a soundtrack for a movie, which didn’t happen. On his way home, he was stranded in London, so I met him and signed him on the spot. I knew a lot about him. I’d even released some of his songs recorded by other artists, but I’d never even met him.”

Chris Blackwell’s gambling instincts paid off when he gave Bob £4,000 up front to make the first Marley album for Island Records. “Everybody said I’d never see that money again. I took that risk and trusted him, and it paid off many times over.”

He feels his gambling instincts were honed to a sharp edge while at a crammer in England, a post-preparatory school that prepares one for University, where he played a lot of poker and bridge with Egyptian schoolmates. “My father wasn’t particularly a regular gambler, but my mother, at eighty-five, has become one,” he smiles. “She’s permanently at the slot machines wherever and whenever possible. She inherited this from me.

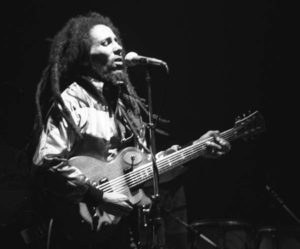

“The first time I knew Bob Marley would be successful was in 1976. It was at a concert here in London – the best concert ever! I had that incredible feeling when you suddenly feel you are at the center of the universe. Now and again, you get that feeling.

“Bob Marley, the first third-world superstar, became a remarkable success just the year before he died in 1981 from a brain tumor. Nevertheless, his legend has just grown and grown. It’s unbelievable how big he is now worldwide. His success was due to his natural sense of pace; he knew how to hold an audience, build an audience, and get his message across. There’ll never be another Bob Marley, just as there will never be another Bob Dylan. It was very, very sad for me when Bob died. He was only thirty-six.”

Blackwell’s “nose” for future star material let him down on several occasions, most memorably “when Joe Cocker, whom I managed, suggested I meet a songwriter and singer whose demos I’d already heard and liked. So when the guy came over to my house in Basing Street, I was prepared to add him to our roster, but, surprisingly, he looked so painfully shy; he just sat on my living room floor and looked more like he wanted to disappear than get signed. I told Joe afterward, `Look, I know the guy is good, but he’s so shy he’ll never be able to get on a stage and perform for an audience. He’s just too shy.'”

Years later, the “shy” man was sitting at the piano playing his composition, “Goodbye, England’s Rose”(a variation on “Candle in the Wind”) live to the world’s largest television audience ever. That man was Elton John, and the occasion was Princess Diana’s funeral at Westminster Abbey in 1997.

“I let Elton go, and he’s become one of the biggest stars ever. I did the same with Pink Floyd. Someone took me to one of their early concerts, and I didn’t get it. I didn’t get their music. It sounded weird to me and their production, all those bubbles on the screen. I just couldn’t see it.”

It was the same for Blackwell with punk and grunge. “I didn’t like that music either; it sold millions of records, but I still didn’t like it, just didn’t get it because, you see, my roots are in black music. Black music places tremendous importance on rhythm — bass and drums. Although I love `attitude’ in music, there’s a place for attitude; I just missed that whole punk thing.”

However, most of the time, Chris has understood what’s good and what will sell. “I really believe,” he says, “that if you’re exposed to the very best, like classical music, even before you recognize it or like it, it goes into your memory bank and gives you a standard to work towards. Fact is, they say that the music you listen to when you’re seventeen to nineteen is the music that will dominate your taste in years ahead, and when I was that age, I listened to the classics and jazz — mostly the jazz.”

IIf it was his father who influenced his musical ear, it was his mother, Blanche, who inspired his aesthetic sense. “She used to insist on taking me to the best museums. I hated going and loathed it, but again, I think that once you’ve seen such things, it’s always in your subconscious, and you develop some taste or “style.”

IIt was this absorbed sense of style that drew him to Roxy Music. “Someone sent me a tape of Roxy Music. I didn’t understand the music, but it all clicked when I saw the design for the album cover by the record’s lead singer, Bryan Ferry, and Anthony Price, the fashion designer. I got it. Images with music have always been important to me, so I’m excited about my new venture, Palm Pictures, which is DVD technology taking music to a new level. DVD is the same size as a compact disc. It looks like a compact disc, but it plays movies and visuals. You put it on; you connect it to your sound system and TV set. You can buy movies on it already, but I believe people will make music-visual things just for this new DVD technology.”

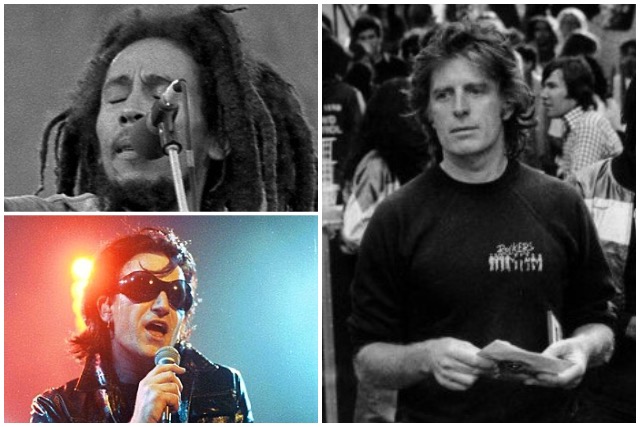

As well as the image, Blackwell is influenced a lot by names. “Names are very important. A man from my press office recommended I check out a band called U2. I was immediately interested in the name alone for two reasons. It’s a great name because you can print it very big because it’s such a small name. On a poster, it looks huge. Secondly, it’s something we say every day. When someone says, `Have a nice day,’ we reply, `You, too.’ I just liked the name.”

Blackwell (left) pictured with U2, (and unidentified others) in 1980, says of their audition, “They didn’t play that great but there was a passion about them, they were real, nothing fake.”

Blackwell went to hear the Dublin lads, U2, at an audition in Herne Hill, South London in July 1980. “I remember it well because it was right after a Bob Marley concert at Crystal Palace, the same night. I can’t say that I recognized and loved their music as much as I loved them, the group.

“They didn’t play that great, but there was a passion about them; they were real, nothing fake. To this day, we’ve remained close friends. When I’m in Dublin, I usually stay with Bono, their lead singer, or Paul McGuinness, their manager in Wicklow. I visit Dublin every year en route to my house in County Mayo.”

U2, Marley, and Cat Stevens remain his biggest-ever acts. “Cat Stevens is now a Muslim called Yousseff Islam; he’s become a real leader in that world. I was brought up as a Catholic but gave it up when I was eight or nine,” he says firmly. “I went to a Catholic school, and when I asked if my dog could go to heaven, I was told that only human beings go to heaven because only humans have souls; that just didn’t make any sense to me. It just didn’t seem right. I still feel that I’m very religious, but I’m not one for joining clubs, especially if they don’t seem to have the right answers.”

You could not say that Chris Blackwell, driven to rebel, has not conformed. “I don’t dress properly in the sense of wearing suits and ties because I prefer comfortable, practical clothes, and I don’t collect things. I was lucky to be born into wealth, so I’ve been there when someone freaks out if an heirloom gets broken, `Oh my, Grandmother would be so upset — that was her favorite crystal glass!’ I can afford it all; it just doesn’t interest me. But I do understand that people who have never had anything need fancy trappings ‘cos it makes them feel they’ve made it, right?”

Even Blackwell, as unpretentious and non-materialistic as he is, must have that inner feeling of having “made it” when he boards his private plane, a Lear Jet, to island hop, checking out his hotels, of which seven are in the Caribbean, and then flying into Miami to visit the other eight hotels, including the Marlin, in South Beach.

“South Beach had a character that had become completely run-down and had been given up for dead by everyone. Nobody even went there. I remember trying to get a cab once, but the driver wouldn’t even come down to South Beach. No one realized quite what had happened to South Beach. The old crowd had died off, and the beach had been completely redone, landscaped, and enlarged. The place was great, but no one went there anymore. I looked at it with European eyes rather than with American prejudices that were writing it off. I thought, `Boy, this is unbelievable,’ so I bought whatever I could.”

Blackwell’s nurturing approach to his hotels is similar to his approach to his music company. “For me, finding and developing a beautiful site is creatively rewarding. In the music business, you find people to work with, engineers, producers, guitarists, keyboard players — you put together the overall picture. Hotels I view the same way. You take designers, architects, and painters and create an exciting, desirable atmosphere and environment.”

As extraordinary as his career, his personal life is equally unique but very complicated. Twice married, Blackwell recently made his partner of ten years, Mary Vinson, the designer, his third bride. They married under a huge mango tree at one of his properties in Jamaica. Naomi Campbell, the supermodel, was a bridesmaid.

“Until fairly recently, I didn’t have any children. Now, I have a five-and-a-half-year-old son. I also have a 32-year-old daughter I didn’t know about until my son was born. And she has a son, too. So, in a short time, I had a Nescafe instant family. Daughter, son, grandson, everything!”

Today, as he looks to his future with Palm Pictures, he talks animatedly of how much more effective he can be at the helm of a small ship crewed by his loyal crew, his “guerrilla force,” some of whom have long been with him.

Chris’ generosity to friends is well known, and it’s poignant to see a giant poster of a smiling Bob Marley and the face of a man who turns out to be Ernest Ranglin, a guitarist who worked for Island Records way back in 1958 and who is now doing some things for Palm Pictures, 40 years on.

As I’m about to leave Chris Blackwell in his friendly HQ, he confides that he sees Waikiki in Hawaii as another possible South Beach. I smile as I notice the raft of neatly arranged colorful brochures advertising his 15 Island Outposts. So he doesn’t collect anything, eh? Who is he kidding?

♦

This article originally appeared in the February/March 1999 issue of Irish America. The video above originally was released in November 2023.

Leave a Reply