He is best known for one part of one poem he published in 1873. Arthur O’Shaughnessy’s “Ode” (which is also referred to by its opening line, “We are the music makers”) actually consists of nine stanzas, but the first three stanzas are the ones of enduring popularity; the rest of the poem, in fact, is typically omitted when appearing in anthologies. But the three opening stanzas, consisting of 24 short lines in total, clearly perform some magic in the eyes of readers and have given rise to numerous pop cultural references over the years.

The “Ode” is an unabashed celebration of the creative calling: “With wonderful deathless ditties / We build up the world’s great cities / And out of a fabulous story / We fashion an empire’s glory.” Also originating from the poem was the phrase “movers and shakers,” the notoriety of which has exceeded that of its creator by an exponential degree.

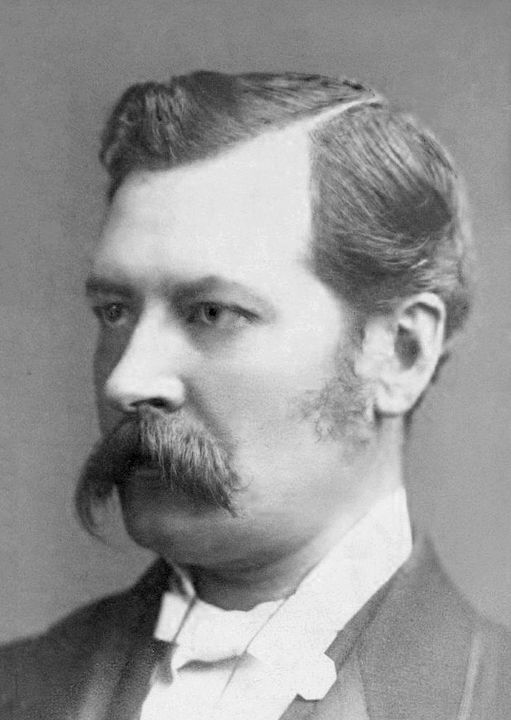

Its creator, Arthur William Edgar O’Shaughnessy, the first of two children, was born in the London borough of Kensington on Mar. 14, 1844. Information about his early life is scarce. Though multiple sources briefly mention that both of his parents were born in Ireland, this information is incorrect. His mother, Louisa Ann O’Shaughnessy née Deacon, was born in 1813 in London. His father, Oscar William O’Shaughnessy, was born in 1816. Though the website wikitree.com says he was born in Ireland, no specific county is mentioned. Writing about O’Shaughnessy in 1964, W. D. Paden tells how the father’s forebears came from County Galway; though Paden does not explicitly say where the poet’s father was born, his article suggests that the father’s actual birthplace was in England instead of Ireland.

O’Shaughnessy’s father was an obscure painter of animals. Whatever his talents amounted to, he had a limited opportunity to showcase them, as he died of consumption at age 31. The absence of a father for most of O’Shaughnessy’s youth contributed to the rumor that he was an illegitimate son of Edward Bulwer-Lytton, a noted writer and politician who was a family friend.

After the father’s death, the remaining family members moved in with the mother’s older sister. Though money was in short supply, it appears that O’Shaughnessy received a good education. While still a youth, he attained fluency in French and expertise on the piano. In fact, his brother (named Oscar, after their deceased father) later became a church organist and music teacher upon emigrating to Chicago.

In 1861, at age 17, Arthur O’Shaughnessy became a transcriber in the British Museum’s Department of Printed Books. Two years later, he obtained a position with the museum’s Natural History Department. In a small subterranean room, O’Shaughnessy, surrounded by pickled specimens of fish and reptiles, spent the rest of his working days.

A colleague at the British Museum described O’Shaughnessy as: “a sort of mystery, revealed twice a day. In the morning, a smart swift figure in a long frock coat, with romantic eyes and bushy whiskers, he would be seen entering the [museum] and descending into its depths, to be observed no more till he as swiftly rose and left it late in the afternoon.”

For many years, O’Shaughnessy gave a sub-optimal effort to his job at the museum. Indeed, he was far more interested in composing poetry and reading French novels. For some time, his superiors at the museum wanted to terminate his employment. However, Edward Bulwer-Lytton – the influential family friend who secured him the job in the first place – helped him keep his job when he underperformed.

Socializing largely in literary circles, O’Shaughnessy wasn’t too keen on telling his friends about his work at the museum, and they had scant interest in hearing about it. He was actually a herpetologist, but based on existing letters, it seems his friends thought he was an ichthyologist. Indeed, these friends – who tended to come from independently wealthy backgrounds, and did not have to do unpoetic things to earn a living – found it amusing that an “ichthyologist” could also fancy himself a poet. They seemed even to doubt the possibility that someone who worked with animal specimens could compose poetry of merit.

In fact, O’Shaughnessy himself felt his job was “potentially detrimental” to his poetic career and abilities, as related in Jordan Kistler’s biography Arthur O’Shaughnessy, A Pre-Raphaelite Poet in the British Museum.

Despite these reservations, the herpetologist-poet published his debut volume of verse, An Epic of Women, in October 1870. The volume received favorable reviews and enabled its author to gain entry into fashionable artistic gatherings. He became friends with such notable creatives as William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Algernon Charles Swinburne. A fluent French speaker, O’Shaughnessy also fraternized with French poets and was a huge fan of Victor Hugo, whom he sometimes visited when vacationing in Paris.

Published in December 1871, O’Shaughnessy’s second poetic volume, Lays of France, received some critical praise but basically no commercial success or notice by the public. His third poetic volume, Music and Moonlight, contained his famous “Ode”; but, as a complete volume, it was a non-factor both critically and commercially upon its March 1874 publication.

Nine months earlier, in June 1873, O’Shaughnessy had married Eleanor Kyme Marston. A woman of considerable wit and intelligence, she was a daughter of the playwright John Westland Marston and a sister of the blind poet Philip Bourke Marston. O’Shaughnessy and his wife proceeded to co-author a book of children’s stories called Toy-Land.

Once he became a married man, O’Shaughnessy showed more interest in holding onto his day job. He even began to write articles for publications related to his line of work and eventually gained some acknowledgment as an authority on reptiles.

But, as his work life became more secure, his personal life spiraled into disarray, owing to events beyond his control. His first child, a son named Westland, died at about six weeks of age. A second son died so young that his birth went unregistered.

Soon after the deaths of these babies, his wife’s mother and younger sister died in quick succession. Understandably distraught, Mrs. O’Shaughnessy’s health, both mentally and physically, began to deteriorate. W. D. Paden relates that she sought to self-medicate with whiskey, and that cirrhosis of the liver caused her death in February 1879, at age 33.

O’Shaughnessy, who himself had long contended with sub-par health, died of pneumonia in London, at age 36, on Jan. 30, 1881, almost exactly two years after his wife. His fourth and final poetic volume, Songs of a Worker, saw publication a few months after his death.

Owing to his work as a herpetologist, his legacy extends beyond poetry and into the realm of taxonomic classification. Among the species that bear his name are the Calumma O’Shaughnessy (a chameleon native to Madagascar), the Pachydactylus O’Shaughnessy (a lizard native to South Africa), and the Enyalioides O’Shaughnessy (a red-eyed wood lizard native to Ecuador; it is also known as O’Shaughnessy’s Dwarf Iguana). ♦

Ode

We are the music makers, And we are the dreamers of dreams, Wandering by lone sea-breakers, And sitting by desolate streams; — World-losers and world-forsakers, On whom the pale moon gleams: Yet we are the movers and shakers Of the world forever, it seems. With wonderful deathless ditties We build up the world’s great cities, And out of a fabulous story We fashion an empire’s glory: One man with a dream, at pleasure, Shall go forth and conquer a crown; And three with a new song’s measure Can trample a kingdom down. We, in the ages lying, In the buried past of the earth, Built Nineveh with our sighing, And Babel itself in our mirth; And o’erthrew them with prophesying To the old of the new world’s worth; For each age is a dream that is dying, Or one that is coming to birth. – The first three stanzas of Arthur O’Shaughnessy’s “Ode”

Leave a Reply